Happy Mother’s Day! Sure, it’s a marketing scam, but we all love moms, right?

Fascinating moms populate literary fiction, and there’s no shortage of great baddies, evil stepmothers, and distant headcases in our favorite literature—but we thought we’d focus instead on some of the moms that seem to be, you know, really great moms.

(See also: Five Favorite Fictional Fathers, Five Favorite Fictional Sons (the daughters list is surely round the bend)).

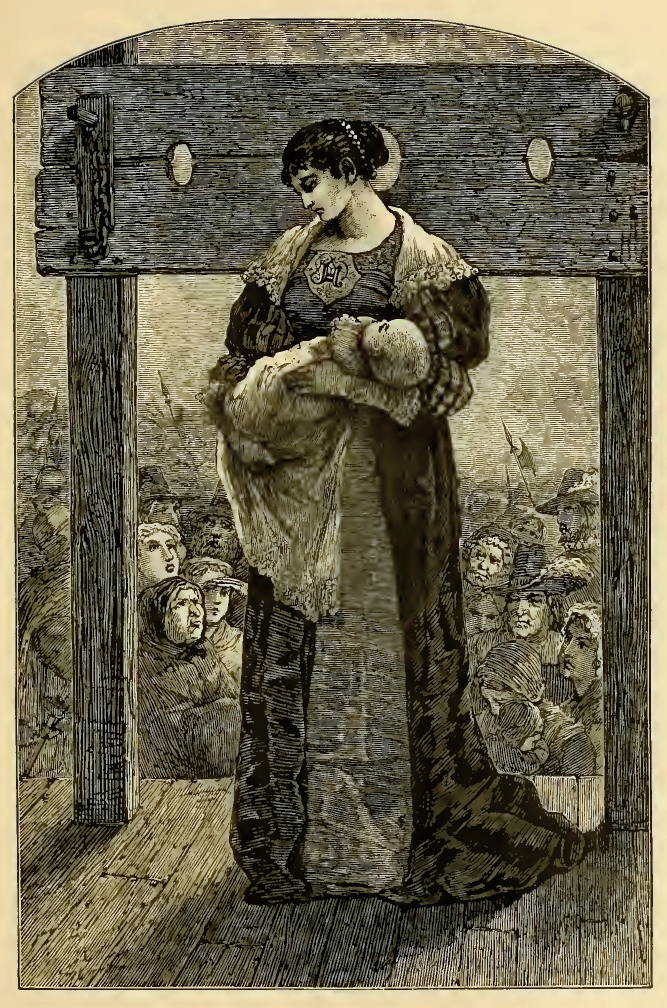

1. Hester Prynne, The Scarlet Letter (Nathaniel Hawthorne)

Hester Prynne is a bundle of contradictions—sin and salvation, radical freedom and reactionary repression, hope and despair—all bound to a deeply patriarchal society that had to control women’s bodies at all turns. Fortunately, there’s no analog for the Puritans’ judgmental, shame-based behavior in our own society (har har). Hester and her daughter Pearl, living in a cottage outside of Boston, are outside the dominant social order. It’s a form of punishment that paradoxically frees the pair, allowing Pearl to grow into a kind of nature spirit—impish and willful, to be sure, but also artistic and able to express herself. Although Pearl is the human doubling of Hester’s titular letter, she’s ultimately no badge of shame, but rather a treasure in her mother’s eyes.

2. Penelope, The Odyssey (Homer et al.)

Patient Penelope weaving and unweaving her husband’s shroud—is she the faithful wife, waiting for Odysseus who’s having adventures asea? Or is she cunningly keeping her son safely alive from the predatory suitors who would certainly want to get him out of the way ASAP. Penelope is an extraordinary and ambiguous figure, but one thing is clear: she loves her son Telemachus.

3. Molly Bloom, Ulysses (James Joyce)

Speaking of Penelope . . . Molly might not be the most faithful wife, but damn if she isn’t a hot mama.

4. Ma Joad, The Grapes of Wrath (John Steinbeck)

Ma Joad never gets a first name in Grapes—she’s an elemental matriarchal force that keeps the family together against every kind of pain. The final scene of this novel is utterly amazing. When Rose of Sharon’s daughter dies in childbirth, Ma Joad directs the mother to nurse a man dying from hunger. All the while, a flood of epic proportions looms. Ma Joad’s determination to live transcends Darwinian impulses here; against the backdrop of infanticide, economic and social genocide, and natural disaster, she still directs her family to a loving, Emersonian course of action.

5. Grendel’s mother, Grendel (John Gardner)

In John Gardner’s fabulous retelling of the Beowulf saga from Grendel’s POV, we find a deeply alienated young man who, try as he might, cannot communicate with the plants and animals around him. Grendel should be a thing of nature, but he is a thinking thing, a thing with a conscience, a soul. He can understand men but they cannot understand him. In one of the book’s saddest conceits, Grendel cannot communicate through speech with his mother, who in many senses seems a creature apart from him. Gardner here dramatizes the radical alienation that all children must feel at some point for their mothers, an alterity grounded in the paradox that, hey, your mom gave birth to you—you came out of her, metaphorically, sure, but also, like, really. Even though Mama Grendel can’t speak to her son, she protects and lovingly cares for him, splitting a few skulls here and there in the process. Motherhood is tough.

And of course, that all-time anti-Mothers’ Day favorite … Lady Macbeth.

Now the Macbeths don’t have children in the play, and they are never mentioned, but we do have the famous lines from I vii: “I have given suck, and know / How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me. / I would, while it was smiling in my face, / Have plucked my nipple from his boneless gums / And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn as you / Have done to this.”

Since Macbeth doesn’t challenge this assertion — “What are you talking about? You’ve never had a child.” — I think it’s reasonable to assert this is true, in the world of the play. What happened to these children? Who knows? But really, it can’t be good.

LikeLike

[…] Five Favorite Fictional Mothers (biblioklept.org) […]

LikeLike