Apocalypse literature, when done right, can inform us about our own contemporary society. It can satirize our values; it can thrill us; it can astound us with its sheer uncanniness. I’m thinking of Russell Hoban’s Ridley Walker, Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novels, Cormac McCarthy’s novels Blood Meridian (yeah, Blood Meridian is an end-of-the-world novel) and The Road, Aldous Huxley’s Ape and Essence and Brave New World. There are many more of course–hell, even the Bible is bookended by the apocalypse of the flood (and Noah’s escape) and the Revelation to John. Then there are the movies, too many to name in full at this point (China Miéville even called for a “breather” a while back), but the ones that work become indelible touchstones in our culture (George Romero’s zombie films and Children of Men spring immediately to mind).

So, my interest in such works foregrounded, perhaps I should get to the business of reviewing Justin Cronin’s massive virus-vampire apocalypse saga/blatant money-making venture The Passage. But before I do, let me get anecdotal: earlier this summer, because of my aforementioned interest in apocalypse lit I tried to listen to the unabridged audiobook version of Stephen King’s The Stand. I bring this up here because Cronin’s book is utterly derivative of The Stand. I also bring it up because I had the good sense to quit The Stand almost exactly half way through–good sense I did not extend to The Passage. Yes, dear reader, I listened to the whole damn audiobook, all 37 hours of it. It helped that I had a home renovation project going that took up most of this week. So I listened to Cronin’s dreadful prose, hacky twists, and derivative plots while sanding joint compound and painting for eight hours at a stretch. True, it’s a much easier audiobook to follow than, say, something by Dostoevsky–but that’s only because anyone with a working knowledge of apocalypse tropes has already seen and heard it all before.

So what is it? In The Passage a government virus turns people into vampire-like zombies with hive mines. There’s a mystical little girl at the center of it all. Does she hold the key to mankind’s salvation? Does all of this sound terribly familiar? Cronin’s book begins in the not-too-distant future, tracing the origins of the virus that will unleash doom and gloom; then, about a third of the way in, he skips ahead about a 100 years to explore what life is like for the survivors. While the commercial prose had taxed me about as far as I could go, I have to admit that this twist a third of the way in intrigued me–what would life be like for these folks? What savagery did the “virals” (also called “smokes,” “dracs,” and a few other names I can’t remember) unleash? Luckily, there’s plenty of exposition, exposition, exposition! Cronin saturates the second part of his novel with so much background information that he essentially ruins any chance the book has to breathe. There’s no mystery, no strangeness–just many, many derivative plots and creaky set-pieces thinly connected with enough chapter-ending cliffhangers to make Scheherazade blush. This wouldn’t be so bad if Cronin’s characters weren’t stock types that would seem more at home in an RPG than, I don’t know, a novel. It’s hard to care about them as it is, but as the novel progresses he frequently puts them in mortal peril and then saves them at the last-minute–again and again and again. The derivative nature of The Passage wouldn’t smart so much if the characters weren’t so flat and the prose so mundane. The action scenes are fine–just fine–but when Cronin gets around to like, expressing themes and ideas the results are risible. It’s like the worst of Battlestar Galactica (you know, those last three seasons), maudlin soap opera that tips into mushy metaphysics.

But I fear I’ve broken John Updike’s foremost rule for reviewing books — “Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.” I think that Cronin has set out to make money here, and he’s written the type of book that will do that, the kind of book that will make some (many) people think that they are reading some kind of intellectual alternative to those Twilight books. There will be sequels and there will be movies and there will be lots and lots of money, enough for Cronin to swim in probably, if he wishes. In the meantime, go ahead and skip The Passage.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden, Helen Grant’s debut novel, negotiates the razor’s edge between childhood’s rich fantasy world and the grim reality of adult life. When young girls start disappearing in her small German village, eleven year old protagonist Pia sets out to investigate, armed with her powers of imagination–an imagination fueled by the Grimmish tales spun by her elderly friend Herr Schiller for the pleasure of Pia and her only friend, StinkStefan. Like poor Stefan, Pia is ostracized by the town after her grandmother spontaneously combusts on Christmas. She takes to playing detective, but as she investigates the girls’ disappearances, the illusions of her fantasy life cannot protect her. As the story builds to its sinister climax, it reminds us that most of the folktales we grew up with are far darker than we tend to remember.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden, Helen Grant’s debut novel, negotiates the razor’s edge between childhood’s rich fantasy world and the grim reality of adult life. When young girls start disappearing in her small German village, eleven year old protagonist Pia sets out to investigate, armed with her powers of imagination–an imagination fueled by the Grimmish tales spun by her elderly friend Herr Schiller for the pleasure of Pia and her only friend, StinkStefan. Like poor Stefan, Pia is ostracized by the town after her grandmother spontaneously combusts on Christmas. She takes to playing detective, but as she investigates the girls’ disappearances, the illusions of her fantasy life cannot protect her. As the story builds to its sinister climax, it reminds us that most of the folktales we grew up with are far darker than we tend to remember.

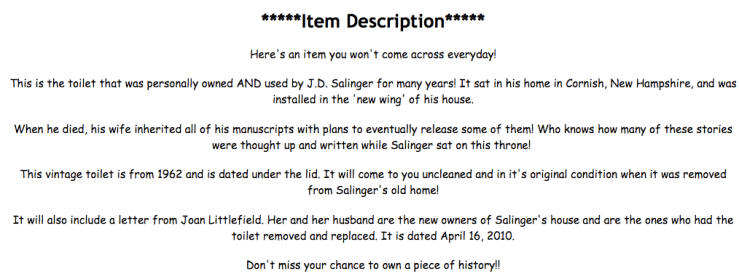

“It will come to you uncleaned”? Wow.

“It will come to you uncleaned”? Wow.

“Hard Read,” from the geniuses at

“Hard Read,” from the geniuses at

Time

Time  In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from

In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from  All My Friends Are Dead by Avery Monsen and Jory John. From

All My Friends Are Dead by Avery Monsen and Jory John. From