1.There’s been a lot of hubbub (at least in my particular echo chamber) the past few weeks about book reviews and the ethics of book reviews:

Too nice?

Too mean?

Just fine?

What about straight-up buying a book review?

And what about when authors get involved, via social media, in calling out reviewers?

2. A sloppy synthesis of what I’ve linked to above might be:

The traditional position of the serious book critic is perhaps being undermined via social media in the hands of well-meaning amateurs.

3. I’m not sure that I exactly agree with the statement above.

4. Still, we live in the Age of the Amateur.

(Saturday Night Live parodied this phenomena in a sketch called “You Can Do Anything!” that hits nail on head).

5. (SNL also unintentionally documented what happens when an amateur is given a forum beyond her untested abilities).

6. I suppose I could spend a few paragraphs parsing the delicate distinctions between literary criticism and book reviews and awarding fucking stars on Amazon or Goodreads, but I think you, gentle reader, probably get all that already.

7. (I consider myself an amateur book reviewer with an interest in but no pretension to literary criticism. I don’t intend to write about myself, but I do feel like I should clarify this).

8. (I know I just said that I don’t intend to write about myself, but again, perhaps germane:

I don’t read a lot of book reviews, especially contemporary book reviews. I mean, I hardly ever read contemporary book reviews. If I’m planning to review the work, a contemporary review may poison any pretense of objectivity I have.

With the occasional new major release, it’s almost impossible not to get a fix on some critical consensus—and I always scan of course.

I usually read a handful of reviews of a book I’m reading after I’ve drafted a review.

And I read lots of old reviews. Lots.

Again, maybe germane to all of this).

9. But I’m riffing out all over the place. Let me get to the point. Let’s return to the second part of Point 2:

The traditional position of the serious book critic is perhaps being undermined via social media in the hands of well-meaning amateurs.

Is this true? I don’t know, exactly. A few points to consider:

Literary criticism has existed via two more-or-less stable forms for about a century now: Academic scholarship and popular media.

Academic scholarship tends to be highly-specialized and literally inaccessible for most people. I think academic scholarship and research about literature is important and I don’t want to knock it all—but most of it simply isn’t exposed to, let alone absorbed by, a reading public.

Popular media—magazines and newspapers—is clearly in a transitional phase. A lot of this boils down to the dissemination of new technologies, the advent of the so-called “citizen journalist,” and the oligarchization of mass media. Journalism, as taught in journalism school, prescribed a set of methods and ethics that seem frankly quaint when set against the internet and 24hr cable networks. How book reviews fit—if they fit at all—into the emerging paradigm of popular media is hard to say.

10. Obviously, one model for how book reviews/lit crit fits into the emerging paradigm of popular media is Goodreads, which I really don’t know much about to be honest. Another is Amazon, which has so many problems I don’t even begin to know how to start. Both of these sites use star ratings though, which has always struck me as probably the worst critical model available.

11. (I got an email recently about Riffle, a new service “powered by the Facebook social graph and loaded with expert curated recommendations.” I mean, how’s that for a shudder down the metaphorical spine?)

12. (Re: Point 11—What is it with this term “curator”? Is it synonymous with: “I produce no original content”?)

13. So, to return to the pretense that I have a point:

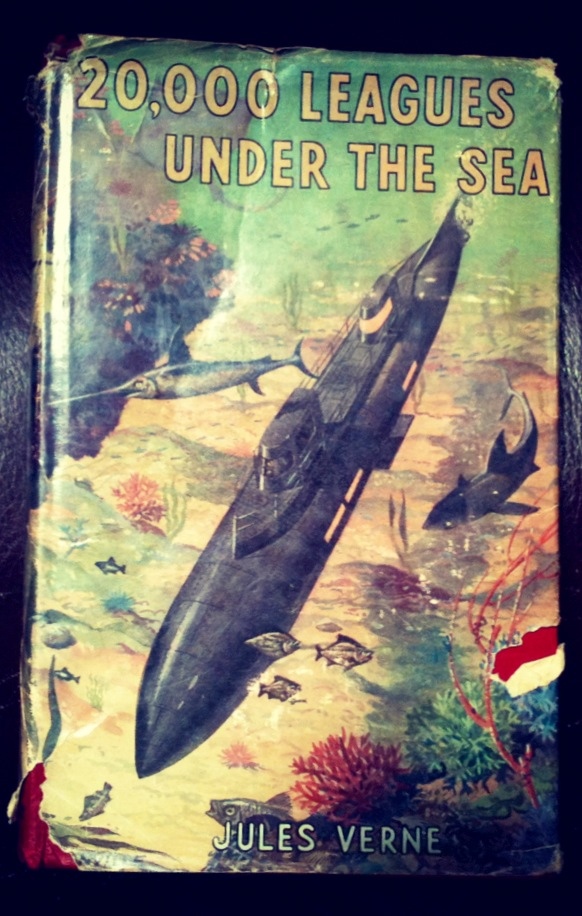

I’ve written about 300 reviews on this site. Most for books, some movie reviews, and a few other things as well (uh, malt liquor). I didn’t really know what I was doing in the beginning—I mean, I wasn’t even intending to review books. I was just writing about books I’d pilfered, pinched. Stolen. (The name of the site was its mission statement). At some point I started making critical judgments, trying to, you know, recommend books that I loved to people who I hoped would love them also.

And at some point I came across John Updike’s rules for reviewing books.

I’m not an Updike fan—wasn’t then, amn’t now—but his rules resonated with me, and I made a point of reading his criticism, which is generally excellent.

In short, I’ve tried to follow his rules.

14. (To clarify: A simple thesis for this whole riff: I think book reviewers need to follow some kind of aesthetic, ethical rubric, one that accounts for subjectivity in an objective way—and I think Updike’s list is great).

15. Updike’s first rule is his best:

Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.

This one seems fairly straightforward, but is abused all the time, whether it’s Kakutani at the NYT pretending YA is not YA, or a reviewer at Book Kvetch lamenting that a metaphor-laced experimental novel isn’t a science textbook.

(I might have abused Updike’s first rule myself, but I’m not going to ransack the archives for self-incrimination).

16. Updike’s first rule is so graceful because it allows for a sliding scale of sorts, a range of possibilities beyond the critic’s own highly-subjective taste.

Put another way, it’s very easy to say, “I loved it” or “I hated it,” but Updike’s first rule places the onus of critical imagination on the reviewer. The responsible reviewer has to understand his or her audience (or at least has to try to understand his or her audience).

17. The subjective can’t be removed from reviews of course—nor should it be. I think the balancing act here might be described as taste.

18. I’ve occasionally broken some of Updike’s rules, especially when I super hated a book (usually #s 2 &3–didn’t bother to cite text—actually, I’ve done this repeatedly),

19. Sometimes a book confuses my approach to criticism.

20. Hence, Adam Johnson’s novel The Orphan Master’s Son, which I reviewed in hardback a few months ago, and which is now available in trade paperback, and which I will use now as some sort of loose illustration for whatever point there is in this ramble:

21. (Okay. So, normally I photograph reader copies (and other books I obtain) and run a little blurb—usually the publisher’s copy or another review—and I was gonna do this with The Orphan Master’s trade paperback (citing my own review in this case), but the post lingered, thoughts accrued around it as I glommed onto all the ideas reverberating around my little echo chamber re: this whole riff. I bring this up in the recognition that a post purporting to address in some way the ethics of book reviewing should point out that the publisher in question (e.g. this blog, e.g. me) regularly posts what amounts to a kind of advertisement for forthcoming books).

22. So why The Orphan Master’s Son?

I use it as example (barring info re: Point 21 for a moment) of a book that didn’t do what I wanted the book to do.

Here’s the end of my review:

Toward the end of The Orphan Master’s Son, I began imagining how the novel might read as a work divorced from historical or political reality, as its own dystopian blend—what would The Orphan Master’s Son be stripped of all its North Korean baggage? (This is a ridiculous question, of course, but it is the question I asked myself). I think it would be a much better book, one that would allow Johnson more breathing room to play with the big issues that he’s ultimately addressing here—what it means to tell a story, what it means to create, what it means to love a person who can not just change, but also disappear. These are the issues that Johnson tackles with aplomb; what’s missing though, I think, is a genuine take on what it means to be a North Korean in search of identity.

I think my review of The Orphan Master’s Son was/is fair, but it didn’t—couldn’t—exactly capture how I felt about the book: a mix of disappointment and admiration.

23. To be clear, I took pains to clarify that I thought highly of Johnson’s prose and that I thought most readers would really dig his book.

I gave it, I suppose, a mixed review, which is almost like giving it a negative review.

24. But I didn’t give it a mixed review to be nice—I tempered my criticisms with the knowledge that any attack I made on The Orphan Master’s Son was really a way of defining my own aesthetic tastes. Let me cite Updike’s fifth rule:

If the book is judged deficient, cite a successful example along the same lines, from the author’s ouevre or elsewhere. Try to understand the failure. Sure it’s his and not yours?

Ultimately, my problem with The Orphan Master’s Son boils down to me wanting Johnson to have written a different book. I feel like I have plenty of reasonable reasony reasons for wanting a different book—first and foremost Johnson’s prowess as proser and storyteller—but that’s no way to review a book. From my review:

I should probably clarify that I think many people will enjoy this novel and find it very moving and that the faults I found in its second half likely have more to do with my taste as a reader than they do Johnson’s skill as a writer, which skill, again I’ve tried to demonstrate is accomplished.

25. Let me end here in repetition (and, perhaps, here in the safety of these parentheses point to how riffing in a rambling wine-soaked list somehow frees me from actually coherently writing about any of the things I promised to—or maybe it doesn’t—which is of course its own ethical ball of worms) by restating a basic answer to some of the basic problems of amateurism:

Book reviewers need to follow some kind of aesthetic, ethical rubric, one that accounts for subjectivity in an objective way.