1. Margaret Atwood’s latest novel, MaddAddam concludes the trilogy she began with Oryx and Crake (2003) and The Year of the Flood (2009).

2. Both of those novels are superior to MaddAddam (Oryx and Crake is the strongest, in my estimation, although I read it almost a decade ago).

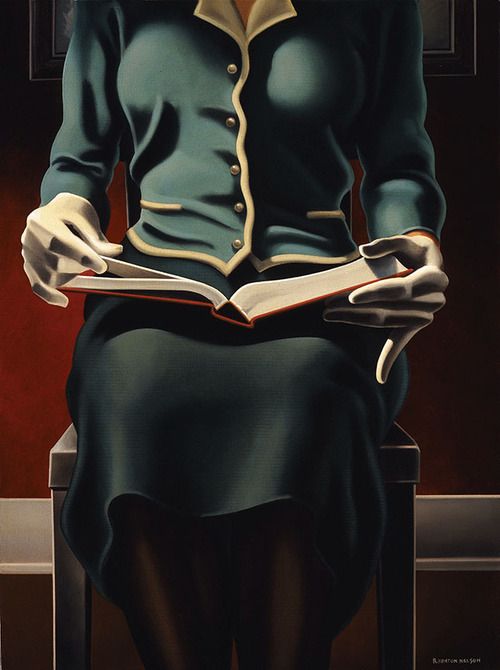

3. I audited the audiobook of MaddAddam, read by Bernadette Dunne, Bob Walter and Robbie Daymond. The actors do a fine job and the production is swell.

4. I am now going to rip off elements of my own 2010 review for The Year of the Flood.

5. In that review I wrote:

Apocalypse lit isn’t so much predictive as it is descriptive of the contemporary world, and Atwood’s dystopian vision is no exception.

I still more or less agree with that sentence, and MaddAddam is, like the two books preceding it, a satire of sorts on modern life.

6. And–

Viscerally prescient, Flood paints our own society in bold, vibrant colors, magnifying the strange relationships with nature, religion, and our fellow humans that modernity prescribes.

I don’t know if it’s me or the book or just the fact that so much of what Atwood conjures in her trilogy seems more real than it was just a decade ago—but MaddAddam didn’t read quite so bold or vibrant as the first two books.

7. I also wrote:

Atwood ends her book in media res, with Toby and a handful of other characters somehow still alive, ready, perhaps, to become stewards of a new world. Flood concludes tense and, in a sense, unresolved, but Atwood implies hope: Toby will lead her small group to cultivate a new Eden. Despite all the ugliness and cruelty and devastation, people can be redeemed.

MaddAddam picks up right where Flood and O&C end (those novels essentially converge). In some ways—often very obvious, sometimes boring ways—MaddAddam provides a sense of resolution for the trilogy’s many threads.

8. What is the book about?

I will lazily slap in publisher Random House’s blurb here, interspersed with my riffage :

Months after the Waterless Flood pandemic has wiped out most of humanity, Toby and Ren have rescued their friend Amanda from the vicious Painballers.

The opening of MaddAddam was a bit too in media res for me: I think the beginning of the book will probably read much smoother if the reader has immediately read the first two books. I had to go reread a summary of the first two books (thanks Wikipedia!) to refresh my old brain.

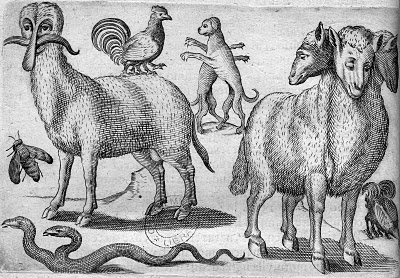

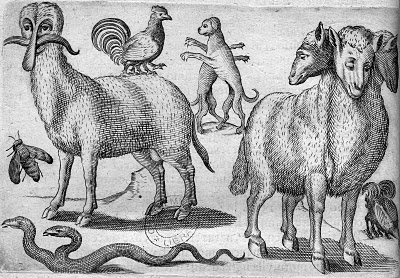

They [Toby/Ren/Amanda] return to the MaddAddamite cob house, newly fortified against man and giant pigoon alike. Accompanying them are the Crakers, the gentle, quasi-human species engineered by the brilliant but deceased Crake.

The Crakers are potentially the most interesting aspect of MaddAddam, but Atwood keeps them on the margins; in the book’s most disappointing moments they’re behavior is basically relegated to punchlines. (Maybe I wanted the book to be an entirely different book—never a fair position for a reviewer to take, but hell, I’ll just say it here in the protection of parentheses—I wanted the book to be about the Crakers in the new world).

Their [the Crakers’] reluctant prophet, Snowman-the-Jimmy, is recovering from a debilitating fever, so it’s left to Toby to preach the Craker theology, with Crake as Creator. She must also deal with cultural misunderstandings, terrible coffee, and her jealousy over her lover, Zeb.

MaddAddam kinda sorta takes the form of an oral history (the novel is polyglossic, fragmented, decentered, blah blah blah). Toby, taking over Jimmy’s storytelling role with the Crakers, essentially invents a mythology. These are some of the best moments of the novel—little riffs on storytelling and memory and legend and myth and history and language and how meaning is made and preserved and transmitted. By the end of the novel, Toby has taught a Craker child—Blackbeard—to read and write. He becomes a translator between the MaddAddamites and the pigoons, but he also takes on the role of storyteller and scribe. He becomes Blackboard, Blackbard.

Zeb has been searching for Adam One, founder of the God’s Gardeners, the pacifist green religion from which Zeb broke years ago to lead the MaddAddamites in active resistance against the destructive CorpSeCorps. But now, under threat of a Painballer attack, the MaddAddamites must fight back with the aid of their newfound allies, some of whom have four trotters. At the center of MaddAddam is the story of Zeb’s dark and twisted past, which contains a lost brother, a hidden murder, a bear, and a bizarre act of revenge.

Atwood devotes most of the novel to Zeb’s backstory, which is mildly entertaining but oh lord! exposition exposition exposition. Even when Zeb’s backstory is conveyed with action and energy, there’s often this constant state of clarification/reminder/callback going on, where the narrative voice has to remind the reader for some reason how the particular event being narrated squares against events in the previous two books.

9. In my review for YotF I wrote

Atwood’s prose sometimes relies on placeholders and stock expressions common to sci-fi and YA fiction, and her complex plot (disappointingly) devolves to a simple adventure story in the end, but her ideas and insights into what our society might look like in a few decades are compelling reading (or, uh, listening in this case).

Okay, so ditto most of that for MaddAddam, only perhaps less compelling. There’s nothing wrong with the simple adventure story that Atwood uses to move her ideas along on here, but there’s also nothing especially engaging either.

10. MaddAddam features an overlong dénouement, culminating in several deaths and births. Even though the ending seems stretched (and often predictable), it nevertheless offers the most cohesive vision in the novel: A future of hybridization and radical diversity that is still beholden to the Darwinian economy of the natural world.

11. The novel resolves by clearing out all of its major characters (sorry if this is a spoiler, but it really isn’t), freeing the imaginative space that Atwood has created—and to be clear, that’s a rich, fertile space—for new adventures, new ways of living, new creatures. I suppose I wanted more What now? explored than the novel had to offer—more exploration of what the genetically-hybridized world might look like with humans no longer the dominant species.

12. But a review (or even a lazy riff) shouldn’t fault a novel for what it doesn’t set out to do. Perhaps leaving the post-flood world barely explored is Atwood’s parting gift to the trilogy’s readers: She offers us a chance to imagine more.