I am rereading Donald Barthelme’s Sixty Stories, starting with the sixtieth story and working my way to the first. I wrote about stories 60-55 here, stories collected in 1981.

This post covers stories 54-49.

54. “How I Write My Songs” (previously uncollected, 1981)

Like his postmodernist contemporaries Robert Coover and William H. Gass, many of Donald Barthelme’s stories are, on at least some level, about the act of writing itself. “How I Write My Songs,” is, as its title suggests, a story about writing. Our narrator the songwriter offers tips and advice, most of it pretty straightforward, and he peppers his monologue with recitations of his own songs. Each time he offers up a song though, we’re treated to copyright notice at the end—little interjections from a faceless corporate voice. The copyright notices are ironic, especially given that the narrator’s songs are clearly based in folk traditions like blues and Appalachian music. The narrator acknowledges these traditions, positing his writing as a synthesis:

Songs are always composed of both traditional and new elements. This means that you can rely on the tradition to give your song “legs” while also putting in your own experience or particular way of looking at things for the new.

In the end, the story’s ironies don’t bite too hard—it it’s a parody of teaching creative writing, it’s loving, and full of practical advice. The narrator’s revelation of his name—Bill B. White—is also a nice punchline.

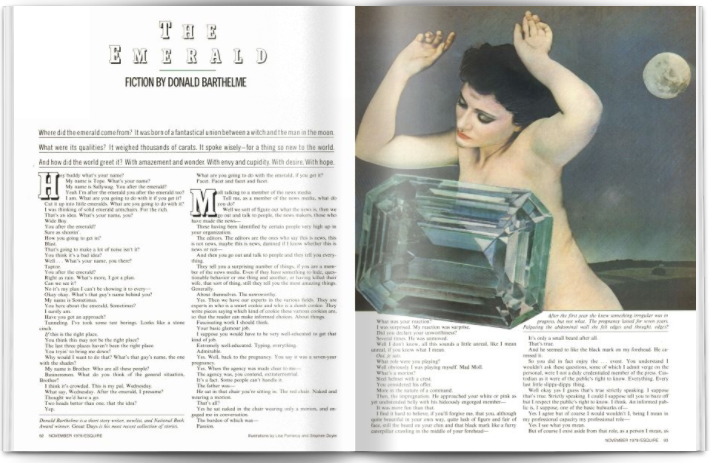

53. “The Emerald” (previously uncollected, 1981)

I love “The Emerald.”

It’s the longest story in Sixty Stories, a 29-page epic that Barthelme culled from an aborted novel, according to Tracy Daugherty’s biography Hiding Man. Unless I’m wrong, it’s the only piece Barthelme published in Esquire; most of his stories showed up in The New Yorker, whose editor Roger Angell was an early champion of Barthelme. Angell rejected “The Emerald” though. In his biography, Daugherty points out that Angell initially did not like Barthelme’s turn toward stories composed entirely in dialogue.

“The Emerald” (and the other stories discussed in this riff) is such a story. Barthelme adeptly commands the various voices here, but without exposition or stage directions of any kind, the story is challenging the first time around. Repeated readings reveal a rich, funny, strange fable.

Here’s what happens: Our hero Mad Moll, a bearded witch, is impregnated by “the man in the moon,” Deus Luna (she has a three-hour orgasm). After a seven-year pregnancy, she gives birth to a sentient emerald. This strange birth attracts the attention of the news media as well as hordes of would-be kidnappers who are after the emerald. Most of the bandits after the emerald want him because, well, he’s an enormous emerald. The emerald understands that they “want to cut me up and put little chips of me into rings and bangles.” When the emerald asks Moll if she values him, she replies that he’s “Equivalent I would say to a third of a sea.” However, our villain, a mage named Vandermaster, has different designs. Vandermaster wants to imbibe the emerald to obtain a second life: “Emerald dust with soda, emerald dust with tomato juice, emerald dust with a dash of bitters, emerald dust with Ovaltine.” He’s discovered a formula, “Plucked from the arcanum,” which will let him live again—and hopefully, find love. Oh, and Vandermaster has a secret weapon: The Foot, a sentient reliquary with devastating powers.

The final moments of “The Emerald” are lovely. Hero Moll gives an exit interview to Lily (“a member of the news media”) in which the young witch states that the gods are not done with us yet:

But what is the meaning of the emerald? asked Lily. I mean overall? If you can say.

I have some notions, said Moll. You may credit them or not.

Try me.

It means, one, that the gods are not yet done with us.

Gods not yet done with us.

The gods are still trafficking with us and making interventions of this kind and that kind and are not dormant or dead as has often been proclaimed by dummies.

Still trafficking. Not dead.

Just as in former times a demon might enter a nun on a piece of lettuce she was eating so even in these times a simple Mailgram might be the thin edge of the wedge.

Thin edge of the wedge.

Two, the world may congratulate itself that desire can still be raised in the dulled hearts of the citizens by the rumor of an emerald.

Desire or cupidity?

I do not distinguish qualitatively among the desires, we have referees for that, but he who covets not at all is a lump and I do not wish to have him to dinner.

Positive attitude toward desire.

Yes. Three, I do not know what this Stone portends, whether it portends for the better or portends for the worse or merely portends a bubbling of the in-between but you are in any case rescued from the sickliness of same and a small offering in the hat on the hall table would not be ill regarded.

Moll’s final questioner though is her child the emerald:

And what now? said the emerald. What now, beautiful mother?

We resume the scrabble for existence, said Moll. We resume the scrabble for existence, in the sweet of the here and now.

52. “Aria” (previously uncollected, 1981)

Another monologue, this time in two paragraphs. Like “Grandmother’s House,” (story #60), “Aria” is an oblique reflection on parenting. In a 1982 interview, Barthelme claimed that the story was a mother’s monologue, but it could just as easily be a father. The monologue condenses the parent’s experience of parenting after the children have left home into an often absurd catalog of pleas, mixed metaphors, and bits of received wisdom. Like a lot of the later work, there are tinges of an empty nester’s melancholy here.

51. “The Leap” (Great Days, 1979)

Another dialogue–however, I think that this piece can actually be read as an internal dialogue–a central consciousness engaging in self-debate. That debate centers (“centers” is a very loose verb here) on whether or not to take the titular leap of faith. As David Gates points out in his explanatory notes for Sixty Stories,

In his Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments (1846),

Kierkegaard rejects the notion of a ladder of logical steps to spiritual certainty in favor of a “leap of faith” toward the Absolute.

Those familiar with Barthelme will know his early deep engagement with existentialism, and with Kierkegaard in particular. (In his biography Hiding Man, Tracy Daugherty makes a strong case that it was not just Kierkegaard’s ideas that informed Barthelme’s work, but Kierkegaard’s style as well—disparate voices, pseudonyms, juxtapositions, aesthetic and literary references deployed ironically, etc.)

The interlocutor(s) of “The Leap” begin by trying to catalog the glories of the creator before realizing that the task is impossible. They eventually work themselves into the existential crises of the day (some of which seem dated, and dare I say, downright lovely compared to our current, ahem, climate).

In the final moments of the story, one of the speakers—or, in my estimation, one of the singular speaker’s internal voices—declares “Can’t make it, man.” What can’t he make? The leap. And again: “Can’t make it. I am a double-minded man.” (The latter phrase underlines the notion that a single voice authors this dialogue.) And so well: “What then?” Barthelme echoes lines of one of his other heroes, Samuel Beckett:

–Keep on trying?

–Yes. We must.

The conclusion is sad and beautiful, a list of earthly consolations that can inspire the leap:

-Try again another day?

-Yes. Another day when the plaid cactus is watered, when the hare’s-foot fern is watered.

-Seeds tingling in the barrens and veldts.

-Garden peas yellow or green wrinkling or rounding.

-Another day when locust wings are baled for shipment to Singapore, where folks like their little hit of locust-wing tea.

-A jug of wine. Then another jug.

-The Brie-with-pepper meeting the toasty loaf.

-Another day when some eighty-four-year-old guy complains that his wife no longer gives him presents.

-Small boys bumping into small girls, purposefully.

-Cute little babies cracking people up.

-Another day when somebody finds a new bone that proves we are even ancienter than we thought we were.

-Gravediggers working in the cool early morning.

-A walk in the park.

-Another day when the singing sunlight turns you every way but loose.

-When you accidentally notice the sublime.

-Somersaults and duels.

-Another day when you see a woman with really red hair. mean really red hair.

-A wedding day.

-A plain day.

-So we’ll try again? Okay?

-Okay.

-Okay?

-Okay.

50. “On the Steps of the Conservatory” (Great Days, 1979)

I initially started rereading Sixty Stories in reverse order as a fluke, but I quickly found it interesting to think about Barthelme’s development as a thinker and writer by going backwards instead of forwards. I think I would have enjoyed “The Farewell” (story #55) much more if I had read it after “On the Steps of the Conservatory,” to which it is the sequel. It’s a neat little parody, but I think the sequel is even funnier, even meaner.

49. “The Abduction from the Seraglio” (Great Days, 1979)

A postmodern riff on Mozart’s opera Abduction from the Seraglio. Barthelme told an interviewer the story originated from an assignment he gave to his writing class that he ended up doing himself. We have pure monologue here; the speaker seems to be a sculptor. He crafts “welded-steel four-thousand-pound artichokes” and plays around on his “forty-three-foot overhead traveling crane which is painted bright yellow.” He occasionally breaks into song.

There are a number of references to architecture and architects in “Abduction.” Again, it’s tempting to read for autobiographical traces here. Barthelme’s father, Donald Barthelme Sr., was a modernist architect who cast a large shadow over his son’s life. But I’m not too tempted by those traces—or, rather, I’m not sure what to make of them, just as I’m not sure of what to make of “Abduction.”

Summary thoughts: “The Emerald” is a fabulous late-period Barthelme–the best in this batch for sure. It’s much, much longer than most of Barthelme’s stories though, so my other pick would be “The Leap.” I didn’t remember “The Abduction from the Seraglio” even as I was rereading it, and I reread it once more before writing about it, and I don’t really think Barthelme pulls it off here.

I’ve enjoyed these late-period dialogue stories, but I’m also looking forward to some new (older) flavors ahead (behind).

I will keep going forward (in reverse) and resume the scrabble for existence, in the sweet of the here and now.