“The best and most skilled of parasites live, reproduce, and die, without their hosts ever really knowing, or at least being able to do anything about it,” declares A.V. Marraccini, early in her new book We the Parasites. “I’m not even a good parasite because painters or novelists can see me seeing them, drawing off their vital fluid, forming new and odd things in my dark-lobed ovarians, and then shoving them out, hastily and fitfully, into the world of papers and reviews.”

We the Parasites belongs in part to that “world of papers and reviews,” that world of criticism, but it also exists on the other side of any genre margin we might wish to impose. A.V. Marraccini’s book is generative, creative, fruitful, a hybrid that points to something beyond the lyric essay. It is stuffed with art and poetry and life; it is erudite and frequently fun; it is moody and sometimes melodramatic, but tonally consistent.

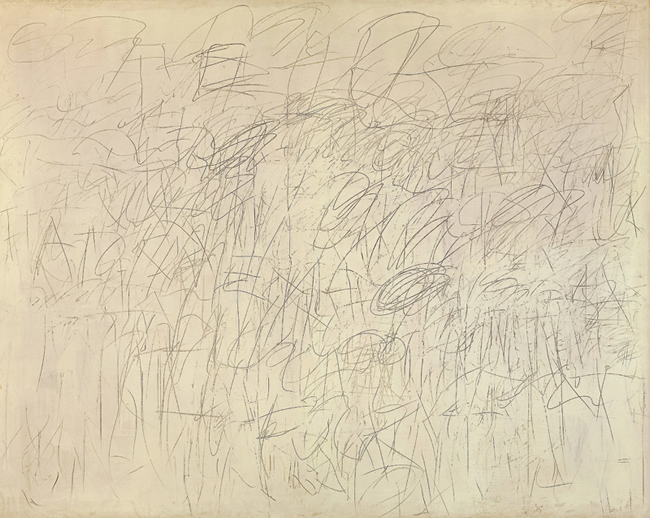

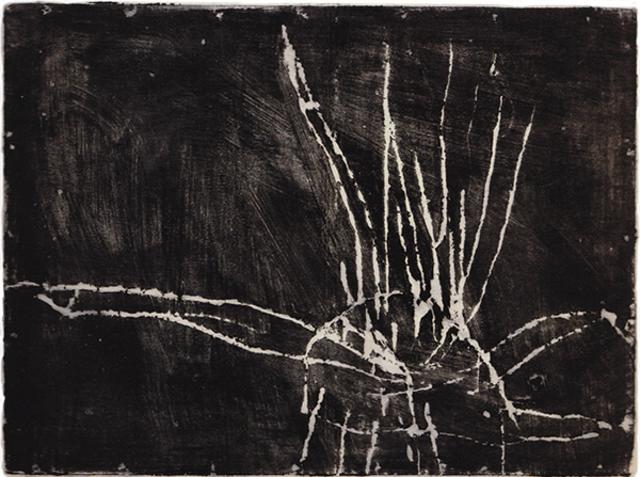

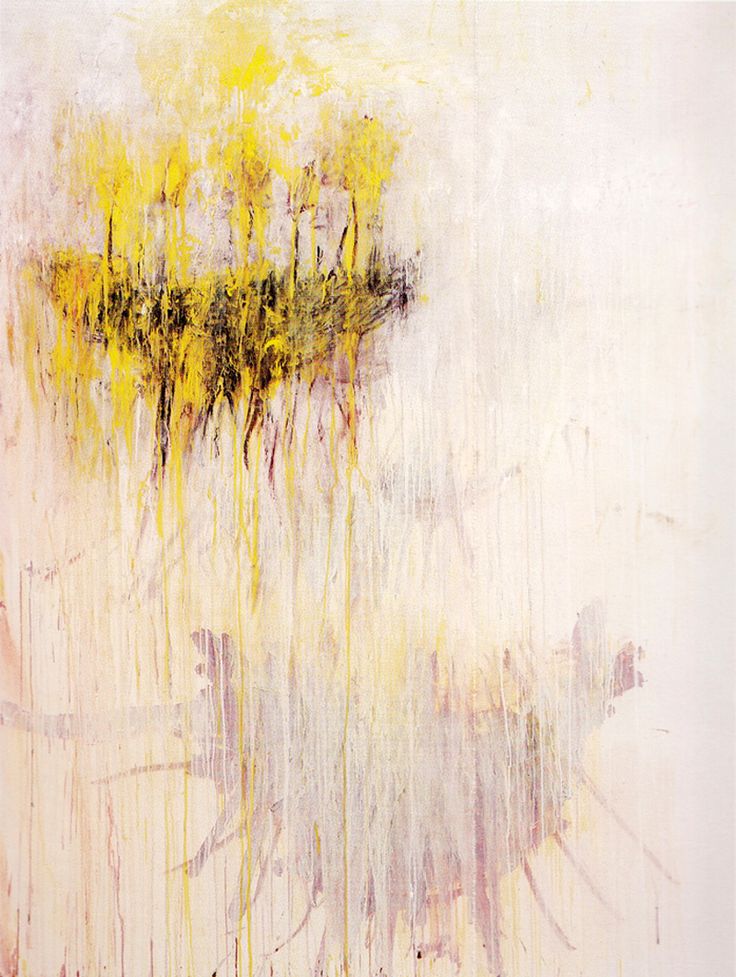

Marraccini’s central metaphor is that critics are parasites. This metaphor gives Marraccini space in which to wander: through history, through art. Through her own history and her present consciousness. She concocts a discursive ekphrasis that zigs and zags from the commensalism of figs and wasps to the paintings of Cy Twombly to John Updike’s novel 1963 The Centaur.

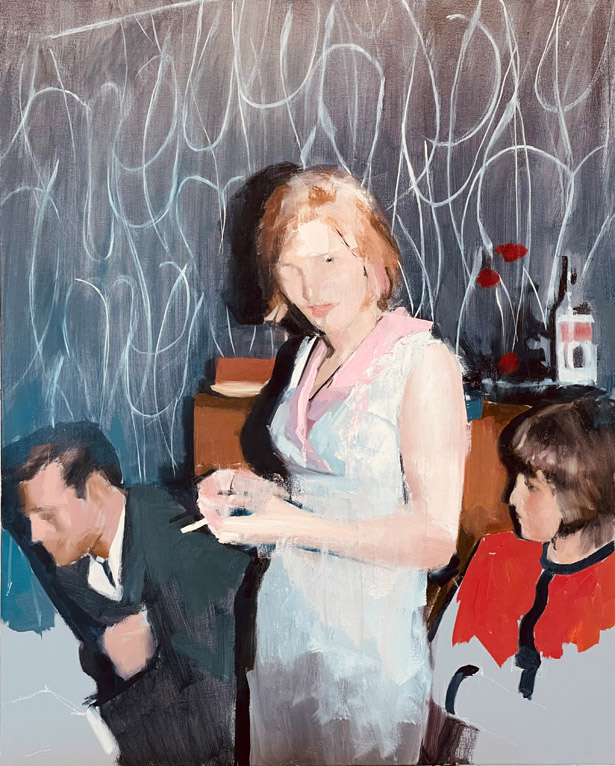

These nimble discursions are one of the primary joys in reading We the Parasites. Marraccini will offer a nice chunk of an H.D. poem before grafting an entire section of Cy Twombly’s Wikipedia page into her text. The particular section Marraccini excises details the so-called Phaedrus incident, in which “Cambodian-French artist Rindy Sam [was arrested] after she kissed one panel of Twombly’s triptych Phaedrus. The panel, an all-white canvas, was smudged by Sam’s red lipstick and she was tried in a court in Avignon for ‘voluntary degradation of a work of art.’ …The prosecution described the act as a ‘sort of cannibalism, or parasitism…'” Marraccini goes on to describe Twombly’s Phaedrus as “a sort of cannibalism or parasitism on Theocritus.”

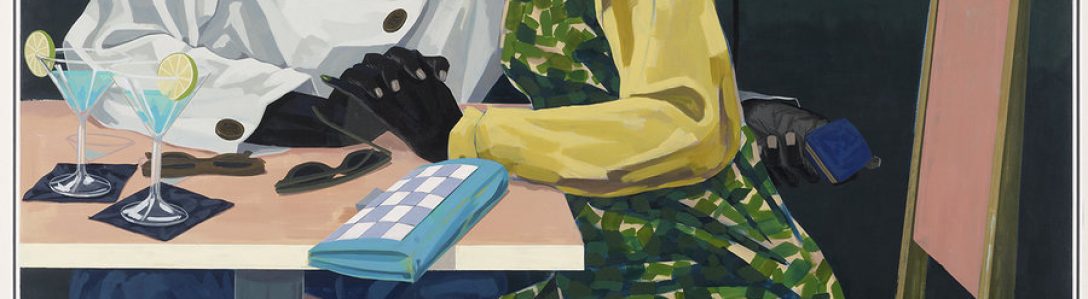

Apart from Marraccini herself, Cy Twombly strikes me as the major figure of We the Parasites. This statement is arguable, as others loom–Alexander the Great, Rainer Maria Rilke, the pseudonymous “Chiron,” one-time mentor to Marraccini who insists she read Updike’s novel The Centaur. But it’s Twombly whom Marraccini most frequently and successfully trains her ekphrastic powers on. Her multivalent reading of Twombly’s 1959 painting The Age of Alexander consumes the end of the book, and no wonder, for she attests that she sees the painting in her sleep, finding in its grafts a symbolic aesthetic language that approaches her own obsessions of parasitism:

Am I “over interpreting” this painting? Probably. It certainly meant nothing about wounds and fish louses to Cy Twombly. Were I writing an historical or academic argument I would have to care then, about the boundary conditions for believability, for perceived intent, and for context. Whatever this is, I’ve now called them off. I can say anything, which is nothing so much as dangerously overwhelming. I do this all the time to the whole world; see it as a layering of partially readable signs and portents, like some unlucky augur forever staring into the guts of sheep, the flightpath of certain birds. This often calls for melodrama, especially when the drama of the world as it really is doesn’t result in any kind of expected catharsis, Aristotelian or otherwise. I map myself onto whatever interpretation I’ve divined for that day, that hour, and then map myself back into the world again in another looping cycle.

While she never states it directly, Marraccini’s appreciation for Twombly’s paintings seems to come as an aesthetic reaction to their hybridity, their apparent incompleteness, their textual overdetermination. Many of Twombly’s paintings seem like studies, unfinished things that the viewer must complete with their own gaze. (Perhaps such thoughts or feelings went through Rindy Sam’s mind right before she kissed Phaedrus.) In a section of We the Parasites that has nothing to do with Twombly, she writes

Sometimes the study is better than the finished thing as it is here, suffused with longing. The provisionality of the study leaves room for it to be free. Right now, like time and the future, language is also provisional, so provisional and free that it feels like you might fall of something huge and intractable every time you write a sentence. There is danger here, with passion, the same frisson always but configured anew. No one is touching anyone’s strange body.

“No one is touching anyone’s strange body.” This is not some tortured metaphor, no. We the Parasites is a stealth plague memoir. 2020 and Covid-19 hang over the book, inverting its would-be-flânerie into flânerie for silent nights, cybernights, flânerie for necessary introversion. We stroll (or jog, or even run) along with Marraccini (a “3 a.m. cryptid”) and her private thoughts, late at night in dead quiet London. She scavenges with some foxes. She names the foxes. She thinks about Twombly; she thinks about an old love; she thinks about “Chiron.”

But We the People is not a straightforward Covid-19 memoir (it is not a straightforward anything)—its memoir intentions are largely aesthetic, often dwelling on Marraccini’s feelings of being an outsider in the Oxbridge world she now inhabits:

I’m a thief; a thousand hundred generations of starving Sicilian farmers indenturing their backs to some steep, rocky crag, a thousand hundred shtetl girls married off young. I’m from a hot, flat suburb of a third-rate city near a swam and the sea, I’m nothing from nowhere to you. I’ve seen the seen the asphalt burble in the heat before a thunderstorm in the summer. Do you think that there are barbarians? That I am one? Well, barbar then.

(Oh, you’re also from Florida? I thought after reading these sentences.)

But I don’t think that Marraccini really would accept the mantle of barbarian. There’s a defensive hedging in some of We the Parasite’s erudition; there are times our author need not try so hard. The prose flows finer (or coarser, as necessary) when the hedges give way: “We always go back to Homer, or I do, the I who wants to be the authoritative we,” Marraccini admits. The next sentence highlights the anxiety inherent in the pretense of critical authority: “I have also always been late to Homer, that same belatedness that creeps up everywhere again.” The anxiety here echoes an early sentiment, one I believe plainly felt by anyone who has ever dared to write about art:

All the battles royale are decided…How do you look at the plain, the beach, the walls of the city, the oak trees and the cauldrons on the tripods over small fires—how do you look at it all and live with the fact that you are always after? Always, somehow, about to break into tenderness and despair?

And yet an abiding love and appreciation and a desire to communicate that love and appreciation overcomes this despair. Like any writer sensitive enough to attend to all the before that they have come after, Marraccini understands the risk and guts it takes to write. The critic may be a parasite, but the critic does not seek to remove art from the world—the critic seeks to enliven the art, to expand its lifeforce:

If I am greedy for, say, a novel, or Bruegel’s Fall of Icarus, or the piano sonatas of the Younger of the Scarlattis, I don’t take it from the world. Or I do, a version of it, and put it in my Simoneidean memory house which is perhaps also a private brothel. But the Bruegel is still there, the Scarlatti, the novel, to seduce other people, other critics. Parasites want their hosts to live so they can spread.

But We the Parasites isn’t exactly a work of sustained criticism, nor is it a lyric essay, nor a memoir. It grafts elements of those genres, in the spirit of works by authors like W.G. Sebald, S.D. Chrostowska, Claudine Rankine, Ben Lerner, and Maggie Nelson. I’ve tried to give enough of a sample of the prose and scope of Marraccini’s book here to let potential readers determine whether or not this is their cup of figs and wasps. I admired much in We the People, and even admired it when it irritated me. I look forward to seeing what Marraccini will do next. Recommended.