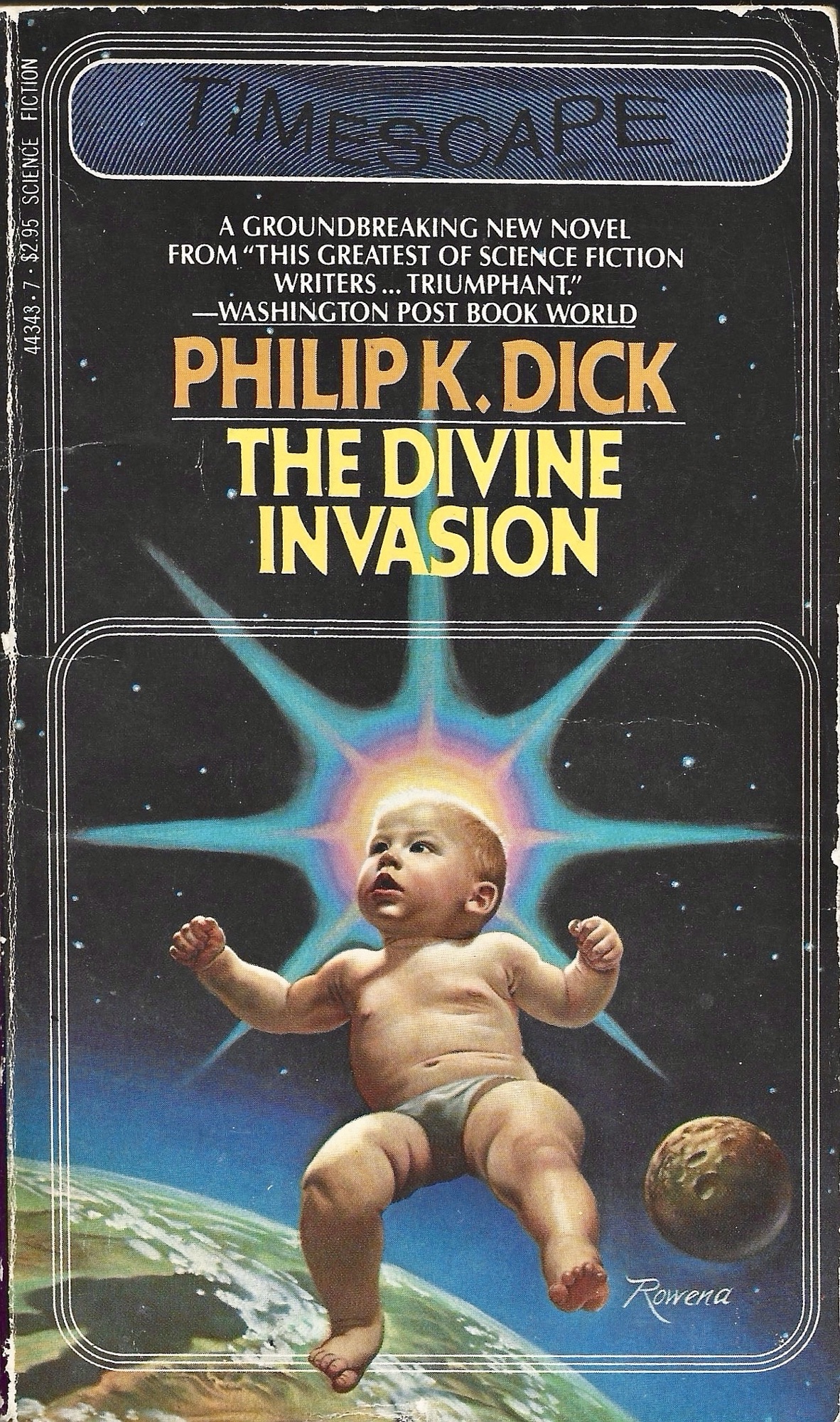

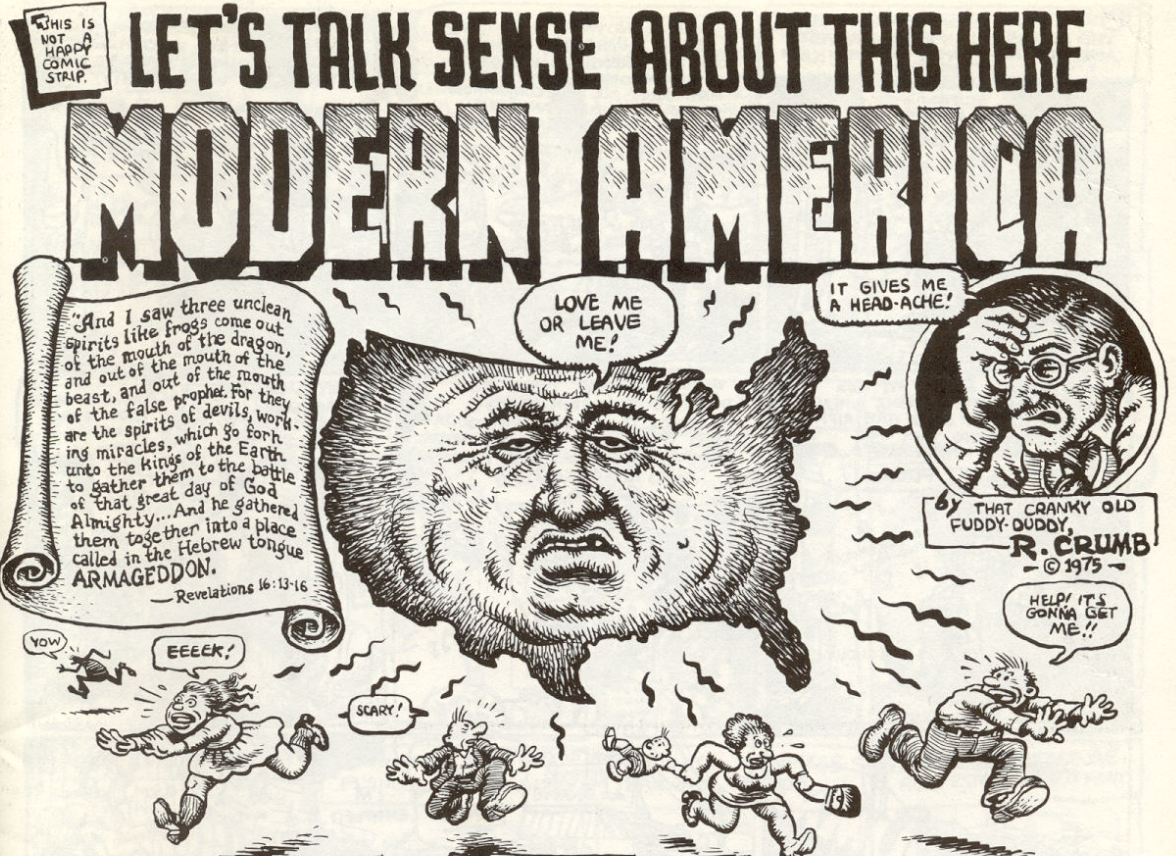

The Moldenke books take place in an abject, stinky, ruinous post-apocalyptic landscape populated with jellyheads, neutrodynes, imps, Stinkers, and Americans. The world runs on broken logic and bureaucratic absurdity. Order is repeatedly disrupted by Chaoses and Forgettings. Bodies fail; technology fails. Ohle relates these stories in a genteel, dry tone (especially in the later books) that mocks any hint of a Hero Saving the Day. His novels, especially those published during US America’s foolish GWOT misadventures, capture the spirit of my country’s farcical post-twentieth-century trajectory.

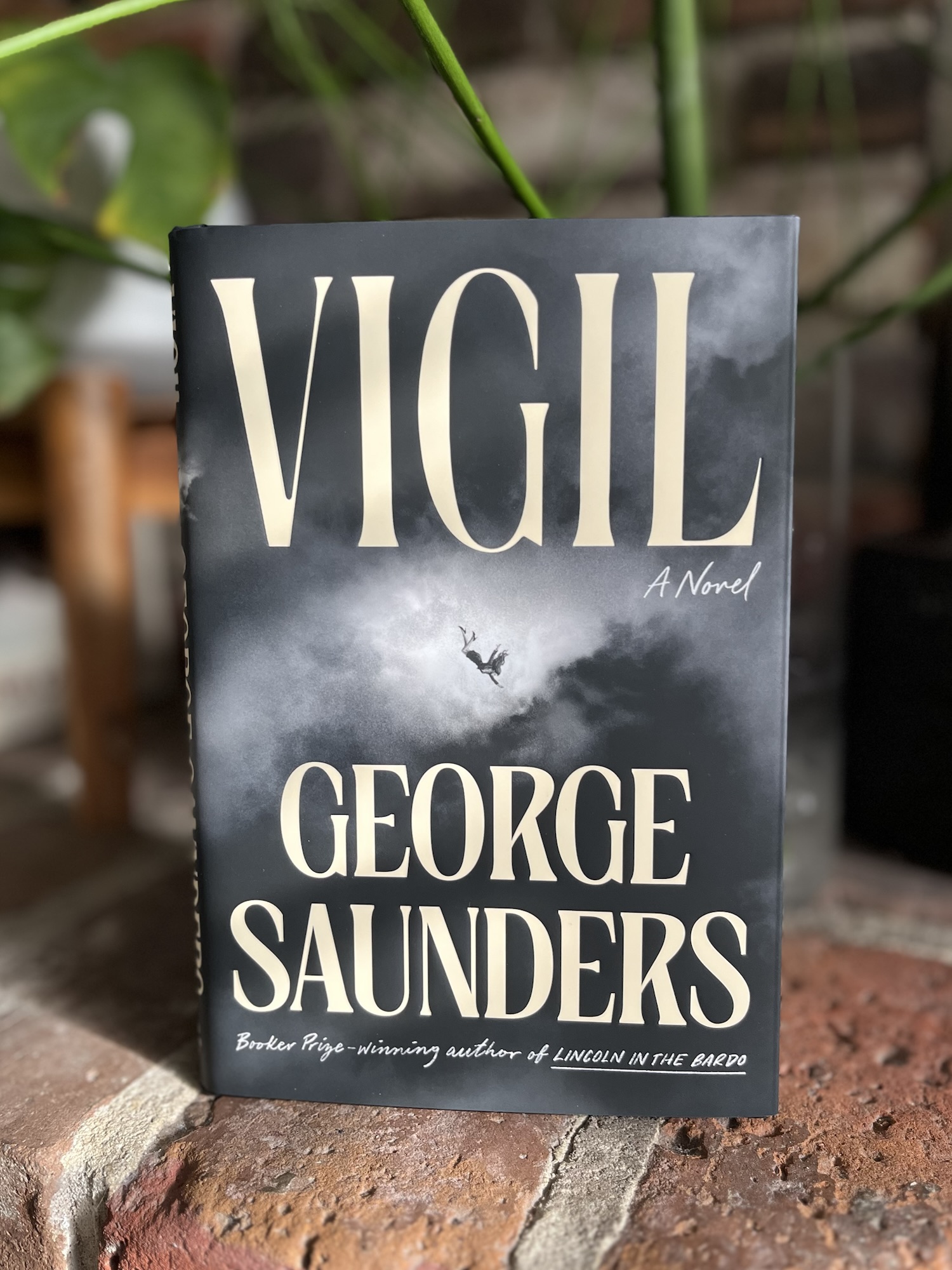

But this blog post is ostensibly about George Saunders, or rather George Saunders’ new novel Vigil, which I have not yet read, having only just today received a review copy in the mail.

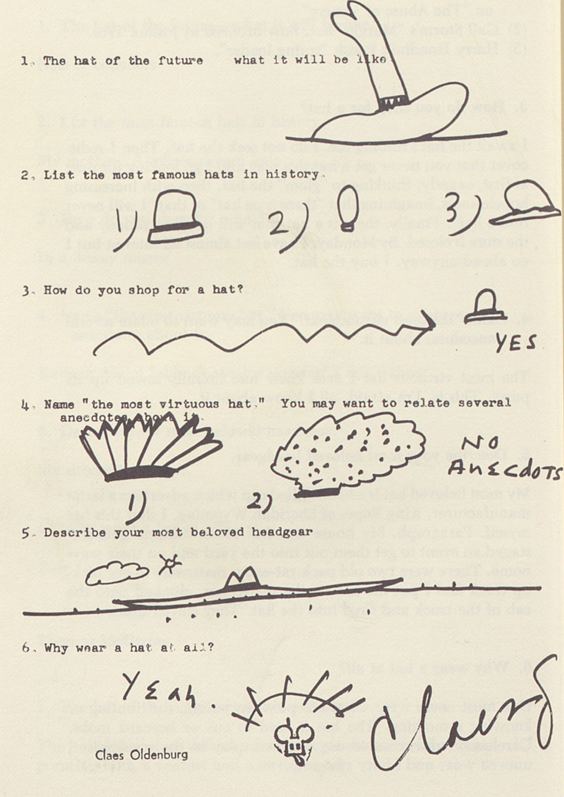

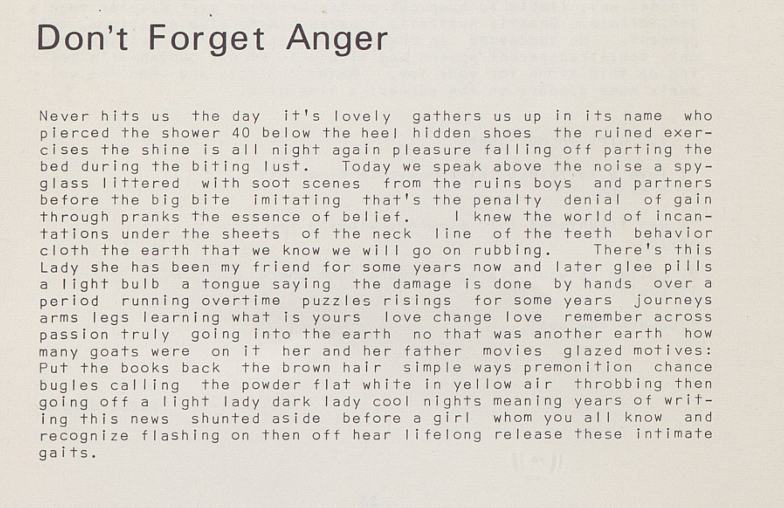

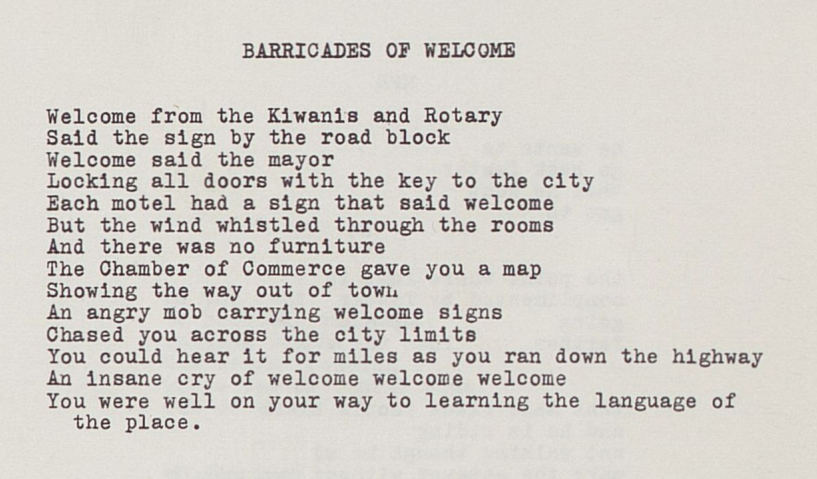

I do not think that a writer has a cultural duty to respond to now, or Now, or even “Now!” if you like–but I do think that Saunders has always aimed to respond to the US American zeitgeist in his fictions. And in the best of his fictions — including the stories “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” “Pastoralia,” “Sea Oak,” and “The Semplica Girl Diaries” — Saunders skewered US American absurdity with a tender pathos that balanced his dark humor without overpowering its core anger. But Saunders’ later fiction is perhaps over-seasoned with love, empathy, all that hippy-dippy shit. It’s not necessary to look through everyone’s eyes. Empathy has its limits. Latter-day Saunders often read to me as, in its worst moments, sanctimonious.

NYT critic Dwight Garner didn’t use the word “sanctimonious” to describe Saunders in his negative review of Vigil, but his lede comes close:

“Once you start illustrating virtue, you had better stop writing fiction,” Robert Penn Warren wrote. It was once difficult to imagine this dictum might apply to George Saunders.

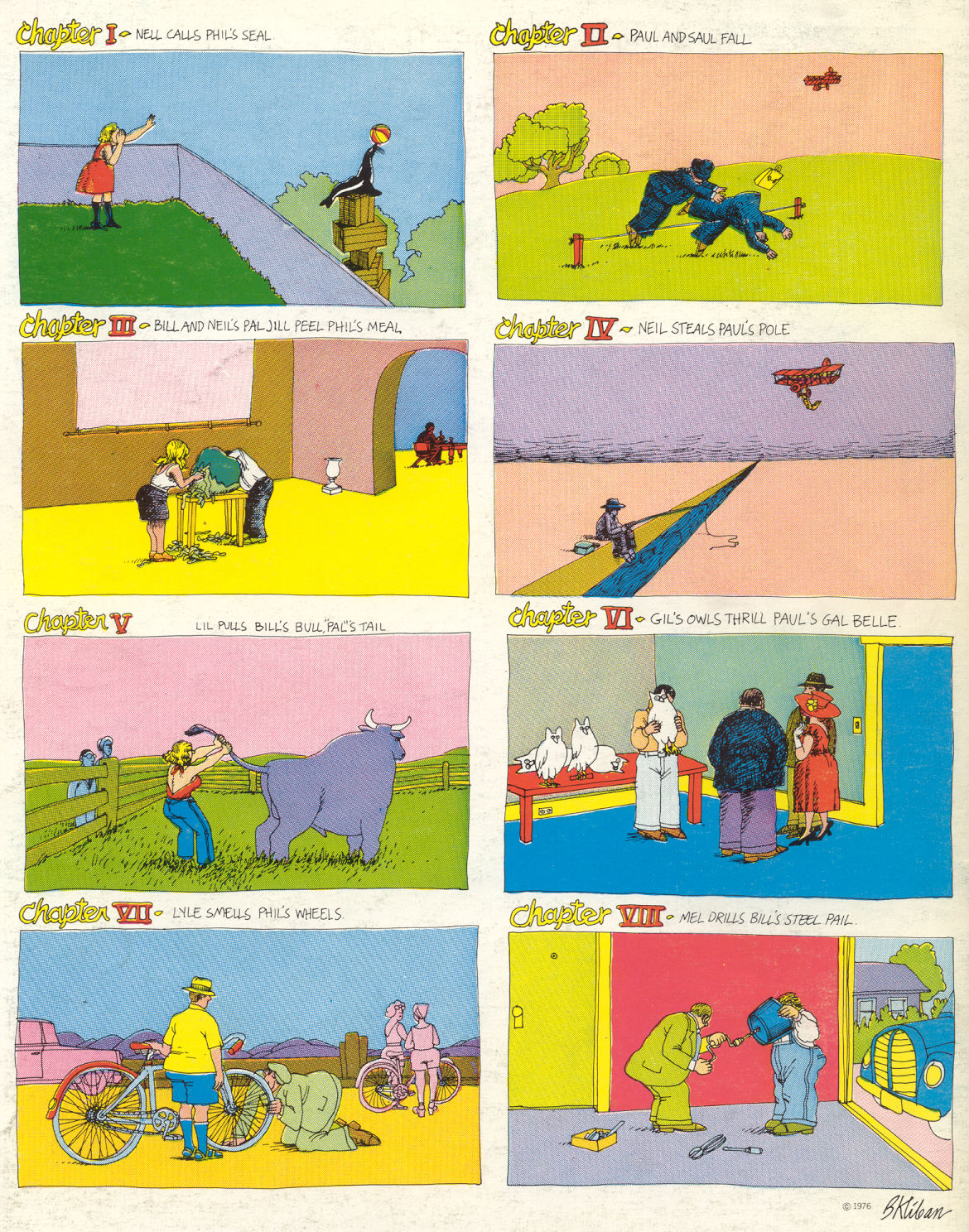

From the start, in the mid-1990s, he’s been an American original, a briskly whiskered national asset. He’s an ineluctably strange, dark and funny writer whose work has some of Mark Twain’s subversive wit, Kurt Vonnegut’s cosmic playfulness and Donald Barthelme’s laboratory blitzing of high and low culture.

It was my colleague who alerted me to this review, which I skimmed, noting the phrase “Downhill Alert!”, before dispensing with it. (My colleague wants me to read the book in some kind of, uh, I don’t know, tandem?, with him.)

This colleague loved Saunders’ 2017 novel Lincoln in the Bardo. I did not love Lincoln in the Bardo. I couldn’t even finish it. I found it maudlin, trite. It was like watching your dad try and impress your boss (I don’t know what that means). I wrote that year, 2017, that—

Lincoln in the Bardo might be a really good novel and I just can’t see it or hear it or feel it. I see postmodernism-as-genre, as form; I read bloodless overcooked posturing; I feel schmaltz. I failed the novel, I’m sure. I mean, I’m sure it’s good, right? The problem is me, as usual.

By 2018 I had changed my mind on that last sentence. I read Saunders’ New Yorker published short story “Little St. Don” and thought it was a massive, massive failure to respond to the incipient fascist encroachment of the first Trump administration. I concluded that,

Saunders loves his reader too much. The story wants to make us feel comfortable now, comfortable, at minimum, in our own moral agency and our own moral righteousness. But comfort now will not do.

I thought Saunders’ next two New Yorker stories were a smidge stronger, calling “Elliott Spencer,” “a stylistically-bold tale about poor people who are reprogrammed and then deployed as paid political protesters.” Of “Love Letter,” I suggested that the exercise “reads like a thought experiment with no real conclusion, no solid answer. Or, rather, the solution is there in the title: love. But is that enough?”

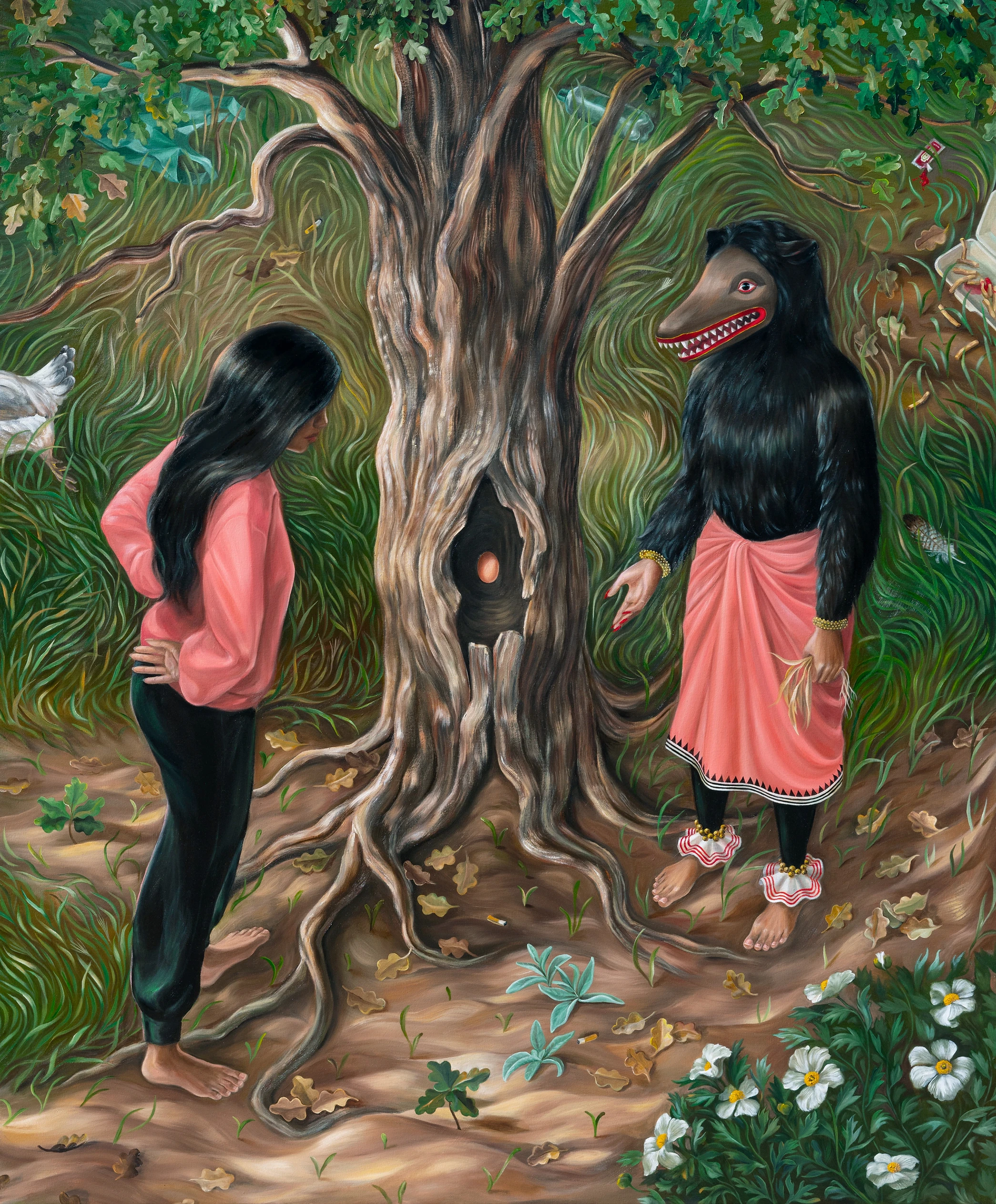

Vigil is about a dying oil tycoon visited by a comforting angel, or series of angels, or something like that. It is, if I understand correctly, Saunders’ take on “climate fiction,” which I imagine will not really dwell in the nasty gross irreal reality of the fall we are falling into right now. But I could be wrong. I can’t help but notice that Vigil seems to be organized, like Lincoln in the Bardo, around a “Great Man” in USAian history — a mover and shaker, a powerbroker, a markmaker, etc. I’ll try to read it with an open mind, but I have to admit that even the prospect pales against my recent dip into Ohle’s sour, funky flavors. But we shall see.