I teach a night class on Wednesdays, and although I enjoy it, I also teach morning sections on Wednesdays, so I’m exhausted when I get home over twelve hours later that night. Anyway, I was thrilled to find a nice little packet from Shocken/Pantheon when I came home last Wednesday—a memoir, a graphic novel, and a book that blends and comments on both.

Meir Shalev’s My Russian Grandmother and Her American Vacuum Cleaner is new in translation from Schocken. Their description—

From the author of the acclaimed novel A Pigeon and a Boy comes a charming tale of family ties, over-the-top housekeeping, and the sport of storytelling in Nahalal, the village of Meir Shalev’s birth. Here we meet Shalev’s amazing Grandma Tonia, who arrived in Palestine by boat from Russia in 1923 and lived in a constant state of battle with what she viewed as the family’s biggest enemy in their new land: dirt.

Grandma Tonia was never seen without a cleaning rag over her shoulder. She received visitors outdoors. She allowed only the most privileged guests to enter her spotless house. Hilarious and touching, Grandma Tonia and her regulations come richly to life in a narrative that circles around the arrival into the family’s dusty agricultural midst of the big, shiny American sweeper sent as a gift by Great-uncle Yeshayahu (he who had shockingly emigrated to the sinful capitalist heaven of Los Angeles!). America, to little Meir and to his forebears, was a land of hedonism and enchanting progress; of tempting luxuries, dangerous music, and degenerate gum-chewing; and of women with painted fingernails. The sweeper, a stealth weapon from Grandpa Aharon’s American brother meant to beguile the hardworking socialist household with a bit of American ease, was symbolic of the conflicts and visions of the family in every respect.

The fate of Tonia’s “svieeperrr”—hidden away for decades in a spotless closed-off bathroom after its initial use—is a family mystery that Shalev determines to solve. The result, in this cheerful translation by Evan Fallenberg, is pure delight, as Shalev brings to life the obsessive but loving Tonia, the pioneers who gave his childhood its spirit of wonder, and the grit and humor of people building ever-new lives.

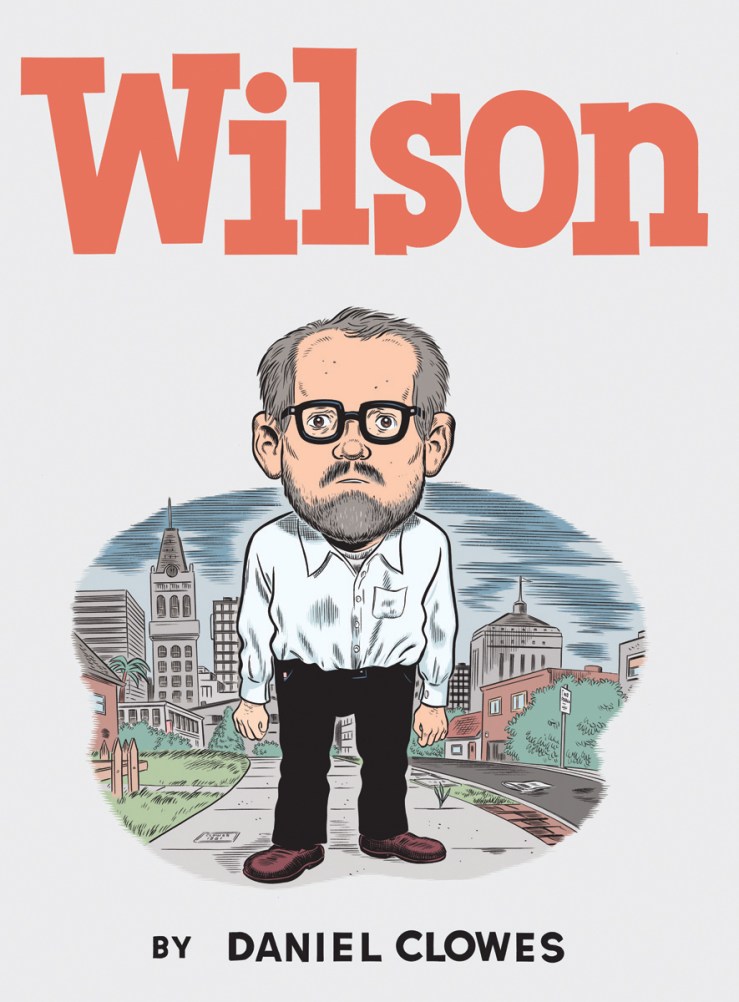

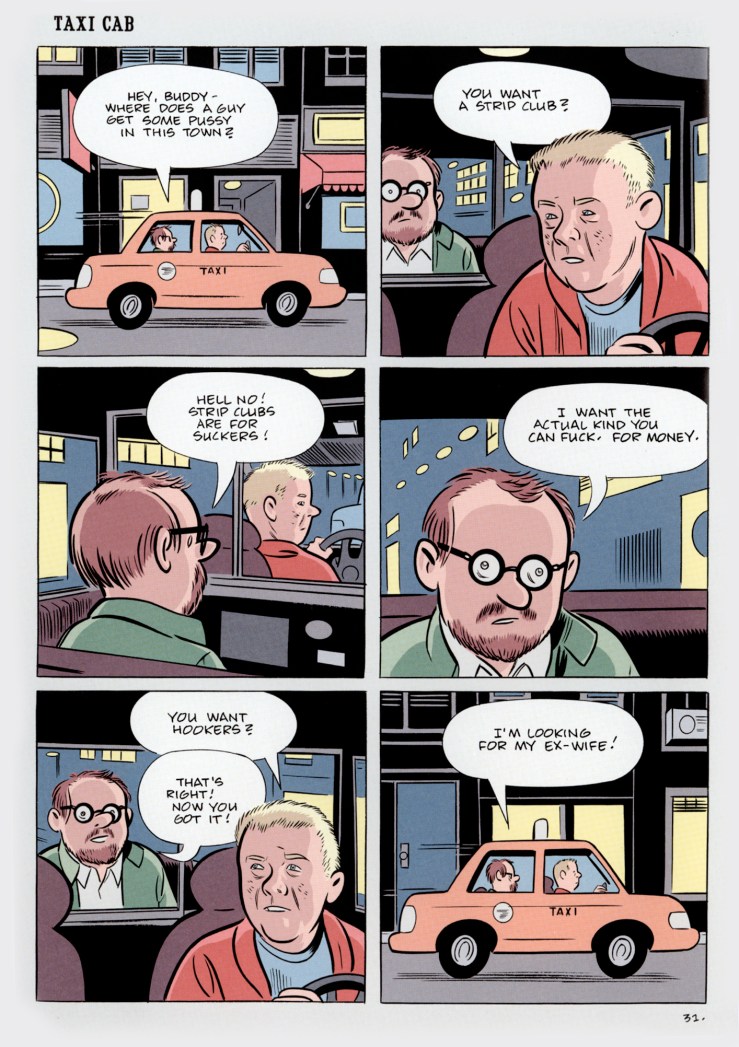

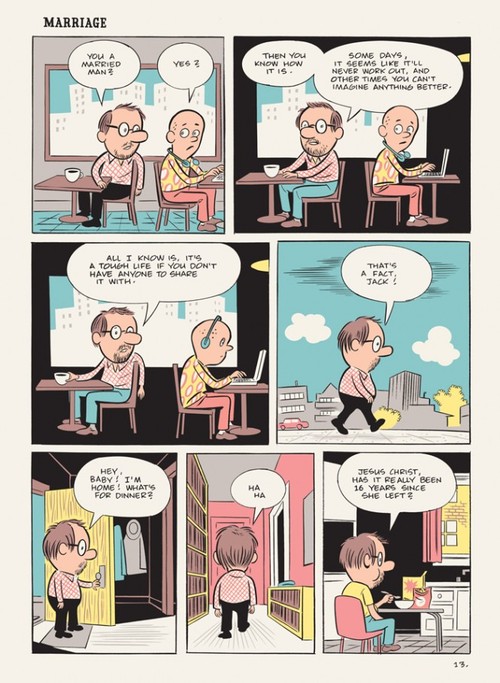

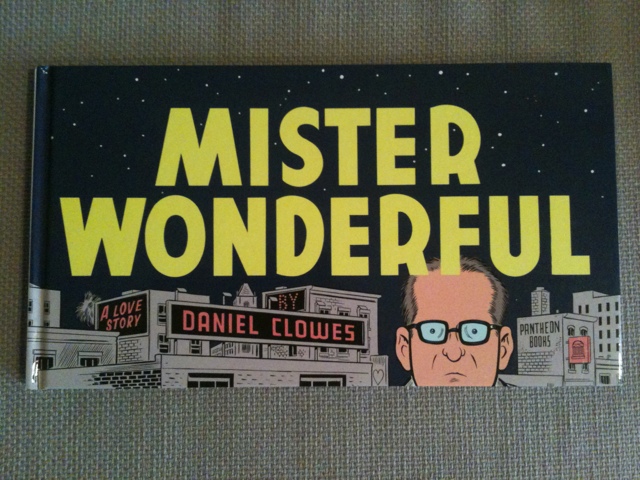

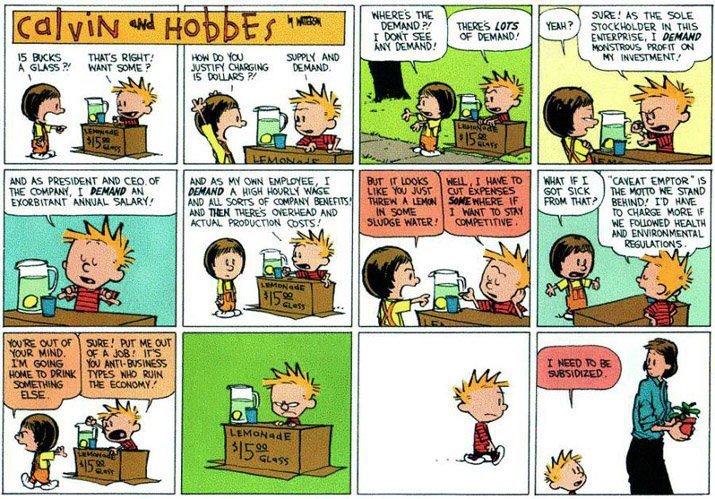

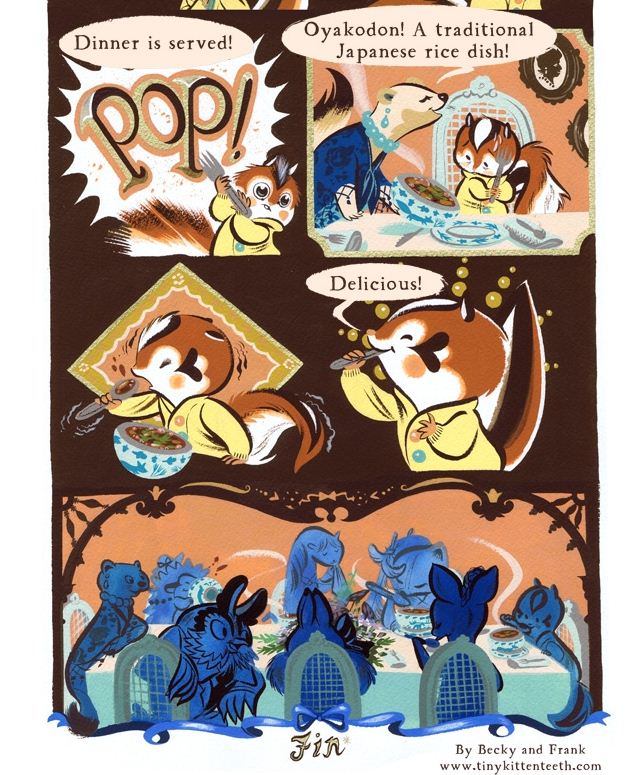

I read Daniel Clowes’s Mister Wonderful that Wednesday night. It was a treat—a wonderful balance of sweetness and acidity. I’m sometimes frightened by how closely I identify with Clowes’s protagonists. Full review next week.

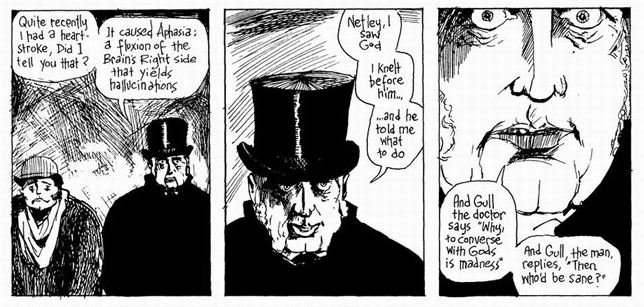

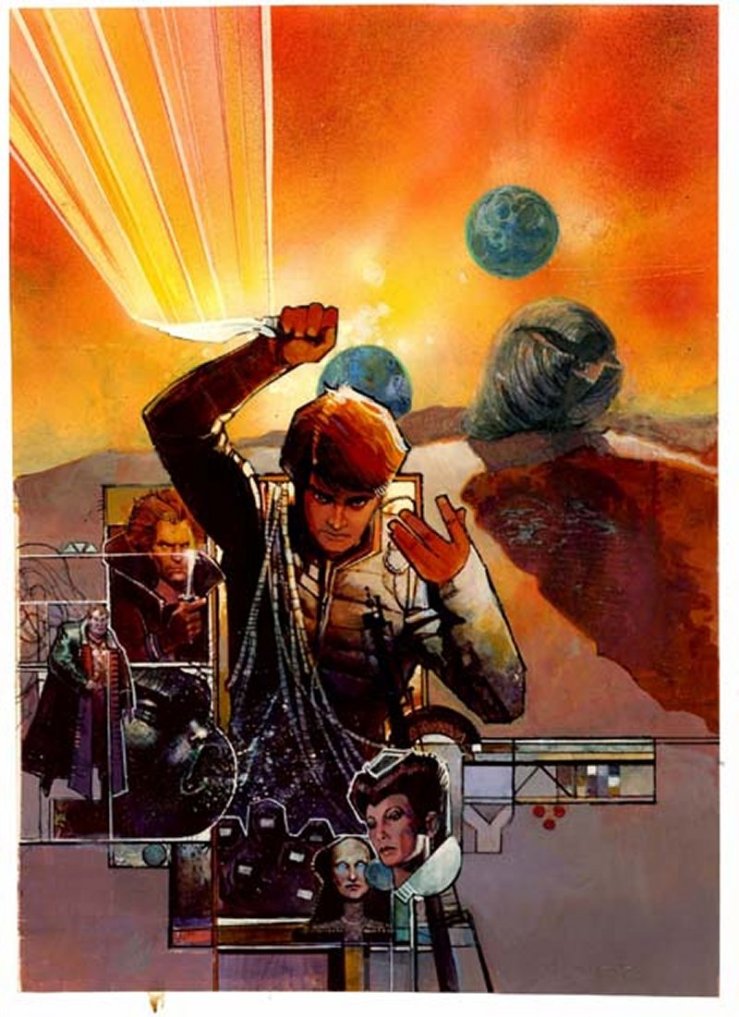

I can’t believe that Art Spiegelman’s MetaMaus hasn’t been remarked upon more—perhaps folks are still digesting it, like me, I guess. I consumed the first 50 pages immediately after finishing Mr. Wonderful, staying up way too late (all of this, accompanied by some mediocre red zin led to a mini-hangover and a generally poor performance teaching classes the next morn). Anyway, MetaMaus is far more engaging than any description of it might suggest. It combines Spiegelman’s cartoons with interviews and other media to detail the process behind creating the original Maus books (or, book singular I suppose is more appropriate). Fascinating stuff, covering memory and art and representation and mice &c. I’ll probably review it in bits and pieces—it seems like too much to process. It also comes with a DVD which I haven’t taken the time to look at yet—-

Read “The Prince and the Sea,”

Read “The Prince and the Sea,”