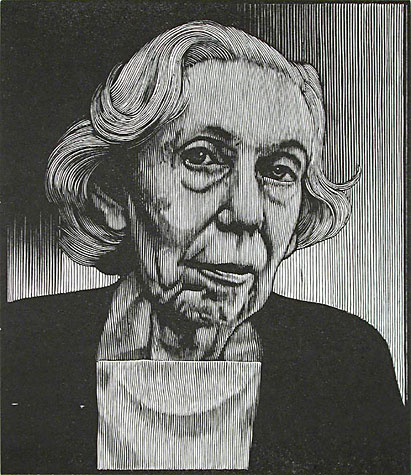

“Lily Daw and the Three Ladies”

by Eudora Welty

Mrs Watts and Mrs Carson were both in the post office in Victory when the letter came from the Ellisville Institute for the Feeble Minded of Mississippi. Aimee Slocum, with her hand still full of mail, ran out in front and handed it straight to Mrs Watts, and they all three read it together. Mrs Watts held it taut between her pink hands, and Mrs Carson underscored each line slowly with her thimbled finger. Everybody else in the post office wondered what was up now.

“What will Lily say,” beamed Mrs Carson at last, “when we tell her we’re sending her to Ellisville!”

“She’ll be tickled to death,” said Mrs Watts, and added in a guttural voice to a deaf lady, “Lily Daw’s getting in at Ellisville!”

“Don’t you all dare go off and tell Lily without me!” called Aimee Slocum, trotting back to finish putting up the mail.

“Do you suppose they’ll look after her down there?” Mrs Carson began to carry on a conversation with a group of Baptist ladies waiting in the post office. She was the Baptist preacher’s wife.

“I’ve always heard it was lovely down there, but crowded,” said one.

“Lily lets people walk over her so,” said another.

“Last night at the tent show—-” said another, and then popped her hand over her mouth.

“Don’t mind me, I know there are such things in the world,” said Mrs Carson, looking down and fingering the tape measure which hung over her bosom.

“Oh, Mrs Carson. Well, anyway, last night at the tent show, why, the man was just before making Lily buy a ticket to get in.”

“A ticket!”

“Till my husband went up and explained she wasn’t bright, and so did everybody else.”

The ladies all clucked their tongues.

“Oh, it was a very nice show,” said the lady who had gone. “And Lily acted so nice. She was a perfect lady–just set in her seat and stared.”

“Oh, she can be a lady–she can be,” said Mrs Carson, shaking her head and turning her eyes up. “That’s just what breaks your heart.”

“Yes’m, she kept her eyes on–what’s that thing makes all the commotion?–the xylophone,” said the lady. “Didn’t turn her head to the right or to the left the whole time. Set in front of me.”

“The point is, what did she do after the show?” asked Mrs Watts practically. “Lily has gotten so she is very mature for her age.”

“Oh, Etta!” protested Mrs Carson, looking at her wildly for a moment.

“And that’s how come we are sending her to Ellisville,” finished Mrs Watts.

“I’m ready, you all,” said Aimee Slocum, running out with white powder all over her face. “Mail’s up. I don’t know how good it’s up.”

“Well, of course, I do hope it’s for the best,” said several of the other ladies. They did not go at once to take their mail out of their boxes; they felt a little left out.

The three women stood at the foot of the water tank.

“To find Lily is a different thing,” said Aimee Slocum.

“Where in the wide world do you suppose she’d be?” It was Mrs Watts who was carrying the letter.

“I don’t see a sign of her either on this side of the street or on the other side,” Mrs Carson declared as they walked along.

Ed Newton was stringing Redbird school tablets on the wire across the store. Continue reading ““Lily Daw and the Three Ladies” — Eudora Welty” →