The Unknown University, Roberto Bolaño’s poetry collection—his complete poems, a bilingual edition, lovely, beautiful, over 800 pages—has been shifted all over my messy house this past month, wedged into ad hoc shelves, even conspicuously, for a time, fatly weighing down another Bolaño text, The Insufferable Gaucho (which I’ve been reading in tandem with/against The Unknown University), swollen and warped with saltwater from the gray Atlantic ocean.

I pecked at The Unknown University discursively, avoiding end notes, taking the rest of the Bolañoverse as my guide or frame or map or background for these poems. I read randomly, trying one poem at a time in no special order, taking crude stabs at the Spanish text on the left hand pages, clumsily matching them against Laura Healy’s fine translation, a poetics that matches the tone and rhythm and cadence and vibe of Bolaño’s other translators, Natasha Wimmer and Chris Andrews.

Then last night, a tale from The Insufferable Gaucho compelled me to read from The Unknown University straightwise, linear, 1-2-3, non-discursively, to take a stab at an orderly trajectory, reading it like a novel in fragments, perhaps.

The book is divided into three parts, each comprised of their own chapters or individual books. Last night I read, or reread, the first half of the first part: The Snow-Novel; Guirat de Bornelh; Streets of Barcelona; In the Reading Room of Hell.

The examples and citations in this riff come from those books, but I’d suggest that the images, motifs, and themes of these early poems—switchblades, hell, abysses, poets, girls, detectives, assassins, hunchbacks, genitals, sex, madness, blood—resonate throughout the entire volume (and throughout Bolaño’s oeuvre).

Perhaps the most central theme is Bolaño himself; The Unknown University often reads like a diffuse autobiography, with Bolaño’s concern for his own place in literature at the fore.

We see that anxiety in the first poem shared by the editors, a piece from 1990 included in the book’s intro:

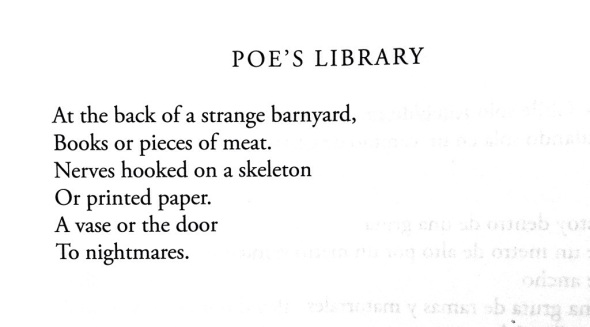

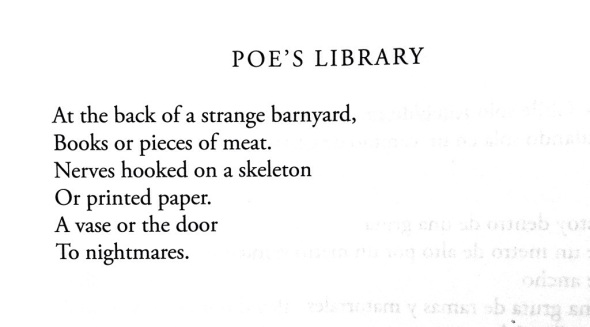

Even a decade earlier, Bolaño prophesied that he would be carried to hell, a primal setting of the Bolañoverse. Bolaño’s romantic ancestor Jorge Luis Borges famously imagined Paradise as a kind of library. Bolaño inverts that image:

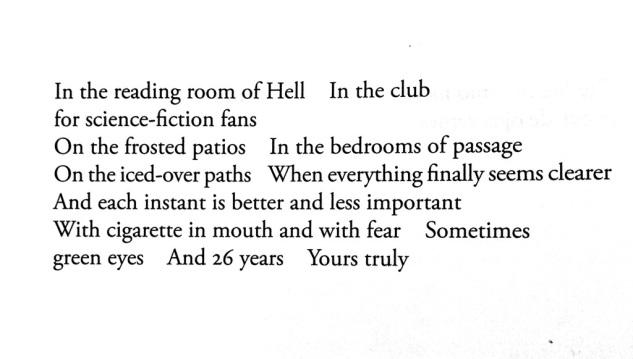

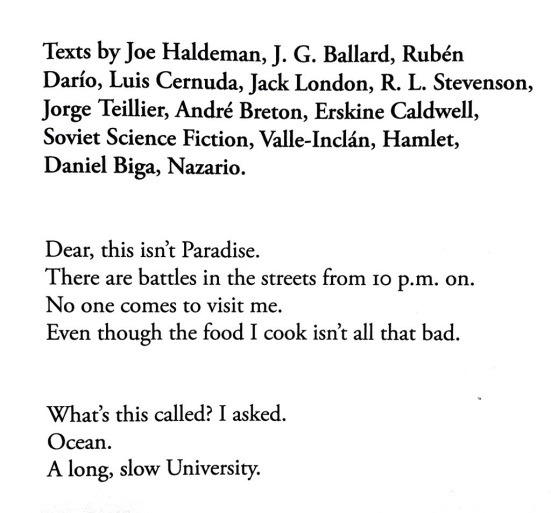

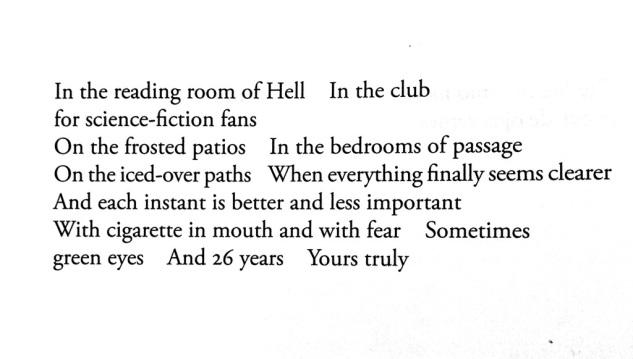

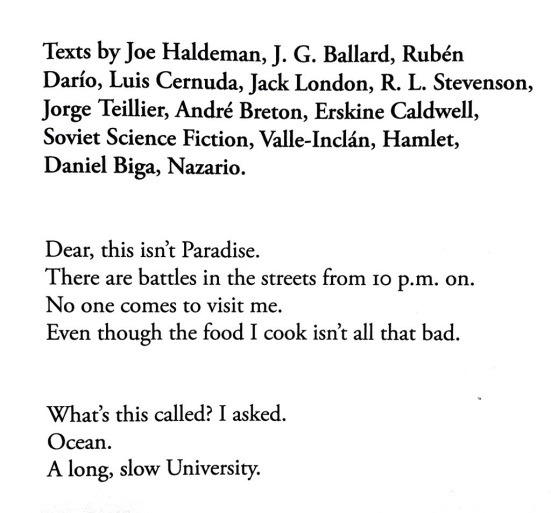

In another poem, Bolaño seems to obliquely address Borges again (“Dear, this isn’t Paradise”), while also name-checking the heroes of that “club / for science-fiction fans” (including some perhaps-unlikely figures):

In another poem, Bolaño seems to obliquely address Borges again (“Dear, this isn’t Paradise”), while also name-checking the heroes of that “club / for science-fiction fans” (including some perhaps-unlikely figures):

“A long, slow University.” Yes.

“A long, slow University.” Yes.

But how could Bolaño leave his hero Edgar Allan Poe from the curriculum? Oh, never mind. Here he is:

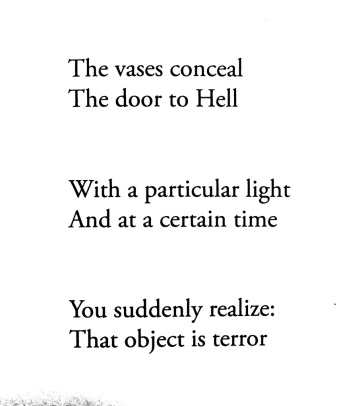

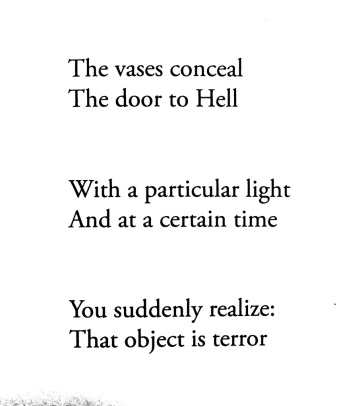

The vase—Pandora’s box, Keats’s urn?—is a central image in these early poems. Dark, beautiful, and transformative, Bolaño seems to posit the vase—an object rendered somewhat mundane in its traditional place as an aesthetic object—as a portal to the abyss:

Elsewhere our poet warns/invites us: “The nightmare begins over there, right there. / Further up, down, everything’s part of the / nightmare. Don’t stick your hand in that urn. Don’t / stick your hand in that hellish vase.” Reading the poem forces us to stick our hand in the vase.

If Bolaño seems occasionally melodramatic in his poems, a thrall to Baudelaire, he’s also keenly aware of it, even this early in his career. A twinning of irony and earnestness characterizes Bolaño’s writing, a savage self-reflexive humor that doesn’t necessarily reveal itself on first reading. When he begins a poem about a lost love, “Go to hell, Roberto, and remember you’ll never stick it in again,” the sentiment is simultaneously tragic and comic, the kind of personal confession that connects to the reader’s own experiences. “To be honest I don’t remember much now,” our narrator confides near the end, before the devastating conclusion, “She loved me forever / She crushed me.”

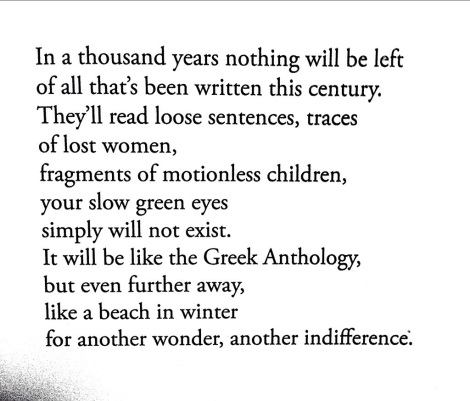

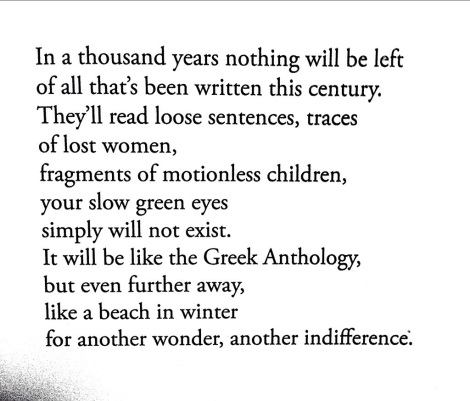

For Bolaño though, what’s perhaps most crushing is the loss of literature:

And yet Bolaño sticks his arm into the vase, walks out over the chasm, dares for his poems to perhaps earn the right to be one of those “loose sentences, traces . . . fragments” that may survive.

In the very early poem “Work,” Bolaño romanticizes his own literary posterity:

Poetry that might champion my shadow in days to come

when I’ll be just a name not the man who wandered

with empty pockets, worked in slaughterhouses

on the old and on the new continent.

I seek credibility not durability for the ballads

I composed in honor of very real girls.

And mercy for my years before 26.

Seems like a reasonable request.

I don’t know if these poems are good or bad or excellent or what. I do know that I loved reading them and that they are of a piece with everything else I’ve read by Bolaño. The best moments recall his best writing, that strange mix of plain, even understated language, set against romantic violence and terrible madness. The poems here don’t distill the best of Bolaño into burning kernels of visceral realism; rather, they feel like the liquid filament of the Bolañoverse. Fantastic.

More to come.

The Unknown University is available now from New Directions.

In another poem, Bolaño seems to obliquely address Borges again (“Dear, this isn’t Paradise”), while also name-checking the heroes of that “club / for science-fiction fans” (including some perhaps-unlikely figures):

In another poem, Bolaño seems to obliquely address Borges again (“Dear, this isn’t Paradise”), while also name-checking the heroes of that “club / for science-fiction fans” (including some perhaps-unlikely figures): “A long, slow University.” Yes.

“A long, slow University.” Yes.