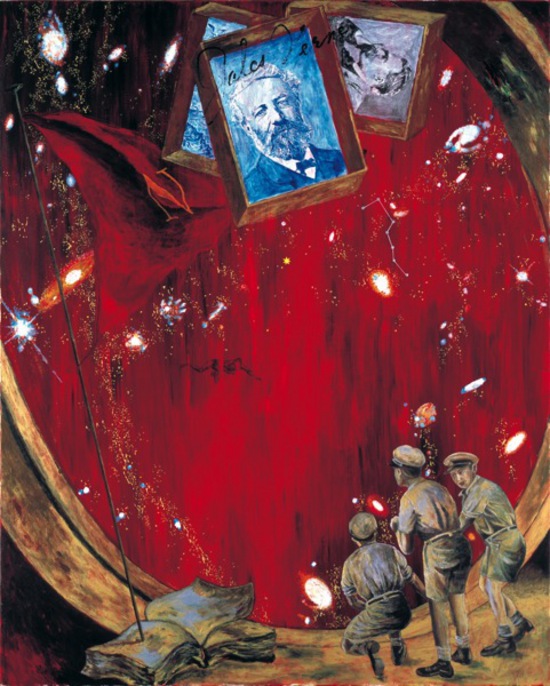

“The Beloved” by Leonora Carrington

ONE LATE afternoon, passing through a narrow street, I stole a melon. The fruit man who was hidden behind his fruits seized me by the arm and said to me: “Señorita, I’ve been waiting for an occasion like this for forty years. I have spent forty years hidden behind this pile of oranges with the hope that someone would steal a fruit from me. I will tell you why; I need to talk, I need to tell my story. If you don’t listen, I will hand you over to the police.”

“I’ll listen,’ I said. Without letting me go, he took me to the inside of the store, among fruits

Without letting me go, he took me to the inside of the store, among fruits and vegetables. We shut a door at the far end, and we reached a room where there was a bed on which an immovable and probably dead woman lay. It appeared to me that she had been there for a long time since the bed was covered with weeds.

“I water her every day,” said the fruitman with a pensive air. “In 40 years I have not succeeded in knowing whether she is dead or not. She has never moved, nor spoken, nor eaten during that time. But the curious thing is that she remains warm. If you don’t believe me, look.”

The man lifted a corner of the cover, which permitted me to see many eggs and some little chicks recently hatched.

“As you notice,” he said, “I incubate eggs here. I also sell fresh eggs.”

We each sat down on one side of the bed and the fruit man began to tell his story.

“Believe me; I love her so much! I have always loved her! She was so sweet! She had little agile white feet. Would you like to see them?”

“No,” I answered.

“Finally,” he continued, after exhaling a deep breath, “she was so beautiful! My hair was blonde; hers, magnificently black! Now, both of us have white hair. Her father was an extraordinary man. He had a mansion in the country. He was a collector of lamb chops. For that we came to know each other. I have a certain skill in drying meat with a glance. Mr. Pushfoot (so he was called) heard about me. He invited me to his house in order to dry his ribs to keep them from rotting. Agnes was his daughter. We loved each other from the first moment. We departed in a boat by way of the Seine. I rowed. Agnes said to me: ‘I love you so much that I only live for you.’ I answered her with the same words. I believe that it is my love which keeps her warm, perhaps she is dead, but the warmth persists.”

After a short pause, with an absent look, he continued: “Next year I will grow some tomatoes; it wouldn’t surprise me if they would grow well there inside … It became night, and I didn’t know where we would spend our wedding night. Agnes had become very pale, because of fatigue. Finally we had scarcely left Paris behind when I saw an inn that faced the river. I moored the boat and we walked toward an obscure and sinister terrace. There were two wolves there and a fox, who began to walk around us. There was nobody else … I knocked and knocked at the door, on the other side of which a terrible silence prevailed. ‘Agnes is tired! Agnes is very tired!’ I shouted with as much force as I could. Finally, an old lady’s head appeared at the window and said: ‘I don’t know anything. The landlord here is the fox. Let me sleep. You are bothering me.’ Agnes began to cry. There was no other remedy than to direct ourselves to the fox. ‘Have you beds?’ I asked several times. Nobody responded: he didn’t know how to speak. And again the head, older than the other, but which now descended slowly through the window tied to the end of a little cord. ‘Direct yourself to the wolves; I am not the landlord here. Let me sleep! please!’ I understood that that head was crazy and I did not have the heart to continue. Agnes kept crying. I walked around the house a few times and finally, I was able to open a window, through which we entered. Then we found ourselves in a kitchen with a high ceiling; over a large oven made hot by fire were some vegetables that were cooking and they jumped in the boiling water, a thing that much amused us. We ate well and then we laid ourselves down on the floor. I had Agnes in my arms. We did not sleep. That terrible kitchen contained all kinds of things. Many rats had stuck their heads out of their holes and then sang with screeching and disagreeable little voices. Filthy odors expanded and diminished one after the other, and there were air drafts. I believe that it was the air drafts that finished my poor Agnes. She never recovered. From that day, each time she spoke less . . .”

And the fruitman was so blinded by tears that I could escape with my melon.