After hearing some positive murmurs praising its erudite maximalism and general zaniness, I caved and bought a copy of Robert S. Stickley’s 2020 novel A Bended Circuity. My copy arrived with a ballpoint flower and the front page signed with a scrawled “R S S.” I can’t really find anything about Big Box Publishing, the purported publisher of this edition, but I do know that the copies of the European reprint at Corona Samizdat sold out pretty quickly. (They have a second printing under way).

Here is the copy from the back of my edition:

There are screams in the night. Interlopers are afoot, have taken hold. Wildfires are burning the countryside and the gentry are running for cover. Fortunes are at stake. The South will not sleep.

A Bended Circuity opens on a midsummer’s afternoon with preparations being made for a soirée at the glamorous Hobcaw Barony. But not all goes according to plan. We soon find Charleston abruptly aroused from her slumber by the playful first smites of an unknown enemy waging a heinous prank war.

Calling his confederates to arms, one Bradley Pinçnit — heir to Marigold Manor and writer for revived southern mouthpiece, The Mercury — afternoon with preparations being made for a soirée at the glamorous Hobcaw Barony. But not all goes according to plan. We soon find Charleston abruptly aroused from her slumber by the playful first smites of an unknown enemy waging a heinous prank war.

Calling his confederates to arms, one Bradley Pinçnit — heir to Marigold Manor and writer for revived southern mouthpiece, The Mercury – organizes and helms a “Junto of Condign Men” then drives them to action. Offsetting her husband’s violent movement is Gabuirdine Lee, a housewife struggling to find her voice as the din of war encompasses her.

Ciphered into everything — the new roadways, the scars of the people, the tracts torn through ravaged plantations — there emerges one clear symbol: The Red Radical. Following the hints offered up by this cryptic motif, an army is mustered and pointed toward north so as to seek justice for the pernicious acts being committed upon an old way of life. But the army will first have to get out of its own way if it is to stand a chance of making it out of the South.

Read the W.A.S.T.E. Mailing List review of A Bended Circuity if you like.

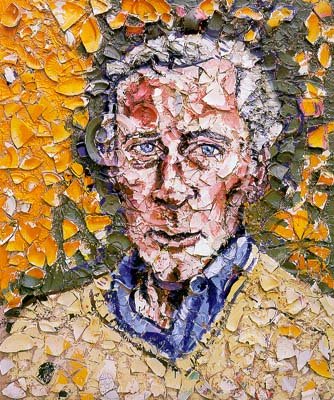

I picked up Thurston Moore’s mammoth memoir Sonic Life yesterday afternoon, started reading it, and kept reading it. I was a huge Sonic Youth fan in my youth, introduced to the band in 1991 via a decent soundtrack to a mediocre film called Pump Up the Volume. Throughout the nineties and early 2000s, I bought all the Sonic Youth records I could get my hands on, and repeatedly watched their 1991 tour diary film The Year Punk Broke more times than I could count. Thurston Moore was a goofy avant hipster, ebullient, verbose, annoying, and endearing, the nexus of a band that were themselves a nexus of nascent bands and artists. (In his chapter on Sonic Youth in his 2001 history Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad repeatedly argues that DGC Records signed the band so that they would reel in the indie groups that majors wanted so badly after Nirvana et al. exploded.) When Thurston Moore and his wife and bandmate Kim Gordon separated in 2011, essentially ending Sonic Youth, I recall being strangely emotionally impacted, like my punk god parents were getting divorced. While I didn’t expect or want dishy answers from Gordon’s 2015 memoir Girl in a Band, I was still disappointed in the book, finding it cold and ultimately dull. So far, Moore’s memoir is richer, denser, sprawls more. It’s written in an electric rapid fire style loaded with phrasing that wouldn’t be out of place in the lyrics of an old SY track. I ended up reading the first 150 or so of the pages last night and this morning, soaking up Moore’s detailed account of the end of the New York punk rock scene and the subsequent birth of No Wave. Moore’s intense love of music is what comes through most strongly. Chapter titles take their names from song titles or song lyrics, and I’ve started to put together a playlist, which I’ll add to as I read:

I picked up Thurston Moore’s mammoth memoir Sonic Life yesterday afternoon, started reading it, and kept reading it. I was a huge Sonic Youth fan in my youth, introduced to the band in 1991 via a decent soundtrack to a mediocre film called Pump Up the Volume. Throughout the nineties and early 2000s, I bought all the Sonic Youth records I could get my hands on, and repeatedly watched their 1991 tour diary film The Year Punk Broke more times than I could count. Thurston Moore was a goofy avant hipster, ebullient, verbose, annoying, and endearing, the nexus of a band that were themselves a nexus of nascent bands and artists. (In his chapter on Sonic Youth in his 2001 history Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad repeatedly argues that DGC Records signed the band so that they would reel in the indie groups that majors wanted so badly after Nirvana et al. exploded.) When Thurston Moore and his wife and bandmate Kim Gordon separated in 2011, essentially ending Sonic Youth, I recall being strangely emotionally impacted, like my punk god parents were getting divorced. While I didn’t expect or want dishy answers from Gordon’s 2015 memoir Girl in a Band, I was still disappointed in the book, finding it cold and ultimately dull. So far, Moore’s memoir is richer, denser, sprawls more. It’s written in an electric rapid fire style loaded with phrasing that wouldn’t be out of place in the lyrics of an old SY track. I ended up reading the first 150 or so of the pages last night and this morning, soaking up Moore’s detailed account of the end of the New York punk rock scene and the subsequent birth of No Wave. Moore’s intense love of music is what comes through most strongly. Chapter titles take their names from song titles or song lyrics, and I’ve started to put together a playlist, which I’ll add to as I read: