At Salon, Ward Sutton provides a pictorial overview of Lewis Hyde’s new book, Common as Air. Great stuff. Thanks to BLCKDGRD for the link.

At Salon, Ward Sutton provides a pictorial overview of Lewis Hyde’s new book, Common as Air. Great stuff. Thanks to BLCKDGRD for the link.

One of the many small vignettes that comprise Jerzy Kosinski’s 1968 book Steps begins with the narrator going to a zoo to see an octopus that is slowly killing itself by consuming its own tentacles. The piece ends with the same narrator discovering that a woman he’s picked up off the street is actually a man. In between, he experiences sexual frustration with a rich married woman. The piece is less than three pages long.

There’s force and vitality and horror in Steps, all compressed into lucid, compact little scenes. In terms of plot, some scenes connect to others, while most don’t. The book is unified by its themes of repression and alienation, its economy of rhythm, and, most especially, the consistent tone of its narrator. In the end, it doesn’t matter if it’s the same man relating all of these strange experiences because the way he relates them links them and enlarges them. At a remove, Steps is probably about a Polish man’s difficulties under the harsh Soviet regime at home played against his experiences as a new immigrant to the United States and its bizarre codes of capitalism. But this summary is pale against the sinister light of Kosinski’s prose. Consider the vignette at the top of the review, which begins with an autophagous octopus and ends with a transvestite. In the world of Steps, these are not wacky or even grotesque details, trotted out for ironic bemusement; no, they’re grim bits of sadness and horror. At the outset of another vignette, a man is pinned down while his girlfriend is gang-raped. In time he begins to resent her, and then to treat her as an object–literally–forcing other objects upon her. The vignette ends at a drunken party with the girlfriend carried away by a half dozen party guests who will likely ravage her. The narrator simply leaves. Another scene illuminates the mind of an architect who designed concentration camps. “Rats have to be removed,” one speaker says to another. “Rats aren’t murdered–we get rid of them; or, to use a better word, they are eliminated; this act of elimination is empty of all meaning. There’s no ritual in it, no symbolism. That’s why in the concentration camps my friend designed, the victim never remained individuals; they became as identical as rats. They existed only to be killed.” In another vignette, a man discovers a woman locked in a metal cage inside a barn. He alerts the authorities, but only after a sinister thought — “It occurred to me that we were alone in the barn and that she was totally defenseless. . . . I thought there was something very tempting in this situation, where one could become completely oneself with another human being.” But the woman in the cage is insane; she can’t acknowledge the absolute identification that the narrator desires. These scenes of violence, control, power, and alienation repeat throughout Steps, all underpinned by the narrator’s extreme wish to connect and communicate with another. Even when he’s asphyxiating butterflies or throwing bottles at an old man, he wishes for some attainment of beauty, some conjunction of human understanding–even if its coded in fear and pain.

In his New York Times review of Steps, Hugh Kenner rightly compared it to Céline and Kafka. It’s not just the isolation and anxiety, but also the concrete prose, the lucidity of narrative, the cohesion of what should be utterly surreal into grim reality. And there’s the humor too–shocking at times, usually mean, proof of humanity, but also at the expense of humanity. David Foster Wallace also compared Steps to Kafka in his semi-famous write-up for Salon, “Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels > 1960.” Here’s Wallace: “Steps gets called a novel but it is really a collection of unbelievably creepy little allegorical tableaux done in a terse elegant voice that’s like nothing else anywhere ever. Only Kafka’s fragments get anywhere close to where Kosinski goes in this book, which is better than everything else he ever did combined.” Where Kosinski goes in this book, of course, is not for everyone. There’s no obvious moral or aesthetic instruction here; no conventional plot; no character arcs to behold–not even character names, for that matter. Even the rewards of Steps are likely to be couched in what we generally regard as negative language: the book is disturbing, upsetting, shocking. But isn’t that why we read? To be moved, to have our patterns disrupted–fried even? Steps goes to places that many will not wish to venture, but that’s their loss. Very highly recommended.

Nearly a year after earning good reviews, Nathan Rabin’s memoir The Big Rewind is now available in paperback (the cover sports the claim that the book now includes “EVEN MORE BITING WIT AND UNWISE CANDOR”). Rabin, if you don’t know, is the head writer for the AV Club, a website I am hopelessly addicted to; he’s also responsible for some of the site’s best regular columns, including “My Year of Flops,” where he revisits films that, y’know, flopped, “THEN! That’s What They Called Music!,” where he subjects himself to listening to and writing about those NOW! CDs, and “Nashville or Bust,” a year-long analysis of country music from an avowed hip-hop fan. If I sound prejudicially predisposed to liking Rabin’s memoir, I am. I can’t help it. In The Big Rewind, Rabin revisits the various pop culture touchstones through which he lived his strange, often sad life–so Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs becomes the lens through which he details his thankless years working for Blockbuster and Nirvana’s In Utero is a key to understanding Rabin’s time in a group foster home. There’s a story arc–depression, a missing mother, suicide attempts, redemption–and plenty of irony to keep it under control. At the same time, there’s too much heart in Rabin’s writing for you not to care. Recommended. The Big Rewind is new in trade paperback from Scribner.

Nearly a year after earning good reviews, Nathan Rabin’s memoir The Big Rewind is now available in paperback (the cover sports the claim that the book now includes “EVEN MORE BITING WIT AND UNWISE CANDOR”). Rabin, if you don’t know, is the head writer for the AV Club, a website I am hopelessly addicted to; he’s also responsible for some of the site’s best regular columns, including “My Year of Flops,” where he revisits films that, y’know, flopped, “THEN! That’s What They Called Music!,” where he subjects himself to listening to and writing about those NOW! CDs, and “Nashville or Bust,” a year-long analysis of country music from an avowed hip-hop fan. If I sound prejudicially predisposed to liking Rabin’s memoir, I am. I can’t help it. In The Big Rewind, Rabin revisits the various pop culture touchstones through which he lived his strange, often sad life–so Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs becomes the lens through which he details his thankless years working for Blockbuster and Nirvana’s In Utero is a key to understanding Rabin’s time in a group foster home. There’s a story arc–depression, a missing mother, suicide attempts, redemption–and plenty of irony to keep it under control. At the same time, there’s too much heart in Rabin’s writing for you not to care. Recommended. The Big Rewind is new in trade paperback from Scribner.

Sloane Crosley’s new collection of memory essays, How Did You Get This Number, finds the witty, observational young lass being witty and observational in and out of New York City–but mostly in. There are trips to Portugal and Paris, and a weird wedding in Alaska. There’s a remembrance of all the childhood pets that didn’t make it. There’s a story about buying furniture of questionable origin off the back of a truck. At times Crosley’s archness can be grating, as dry observations pile one upon the other, but her gift for exacting, sharp detail and her willingness to let her guard down at just the right moment in most of the selections make for a funny and compelling read. I’m still not sure why there’s no question mark in the title, though. How Did You Get This Number is new in hardback from Riverhead Books.

Sloane Crosley’s new collection of memory essays, How Did You Get This Number, finds the witty, observational young lass being witty and observational in and out of New York City–but mostly in. There are trips to Portugal and Paris, and a weird wedding in Alaska. There’s a remembrance of all the childhood pets that didn’t make it. There’s a story about buying furniture of questionable origin off the back of a truck. At times Crosley’s archness can be grating, as dry observations pile one upon the other, but her gift for exacting, sharp detail and her willingness to let her guard down at just the right moment in most of the selections make for a funny and compelling read. I’m still not sure why there’s no question mark in the title, though. How Did You Get This Number is new in hardback from Riverhead Books.

I just got my advance review copy of James Ellroy’s forthcoming memoir The Hilliker Curse, so I haven’t had time to read much of it, but the story so far is morbidly fascinating (like, you know, an Ellroy novel. But this is real. Because it’s a memoir). In 1958, James’s mother Jean Hilliker had divorced her husband and begun binge drinking. When she hit him one night, the ten year old boy wished that she would die. Three months later she was found murdered on the side of the road–the case remains unsolved. The memoir details Ellroy’s extreme guilt; his sincere belief that he had literally cursed his mother pollutes his life, particularly in his complex relationships with women. Full review forthcoming. The Hilliker Curse is available September 7th, 2010 from Knopf.

I just got my advance review copy of James Ellroy’s forthcoming memoir The Hilliker Curse, so I haven’t had time to read much of it, but the story so far is morbidly fascinating (like, you know, an Ellroy novel. But this is real. Because it’s a memoir). In 1958, James’s mother Jean Hilliker had divorced her husband and begun binge drinking. When she hit him one night, the ten year old boy wished that she would die. Three months later she was found murdered on the side of the road–the case remains unsolved. The memoir details Ellroy’s extreme guilt; his sincere belief that he had literally cursed his mother pollutes his life, particularly in his complex relationships with women. Full review forthcoming. The Hilliker Curse is available September 7th, 2010 from Knopf.

Proving that he’s the kind of elitist Harvard-educated snob who reads literature, President Barack Obama picked up an advance copy of Jonathan Franzen’s forthcoming novel Freedom today. Obama also picked up copies of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird and John Steinbeck’s The Red Pony for daughters Sasha and Malia (spoilers for S & M, undoubtedly faithful Biblioklept readers both: Boo Radley isn’t so bad, that white dude raped his daughters, and they have to kill the pony’s mama. But not all in the same book). Also, our president is photographed outside the bookstore wearing what appears to be socks and sandals. (Okay, looked like socks and sandals in the light. But we’ll give BO the benefit of the doubt).

“Tao Lin Will Have the Scallops” by Christian Lorentzen. I’m about halfway through Lin’s forthcoming novel, Richard Yates, which is somehow both far out and totally banal at the same time. Its cover is pretty awesome–

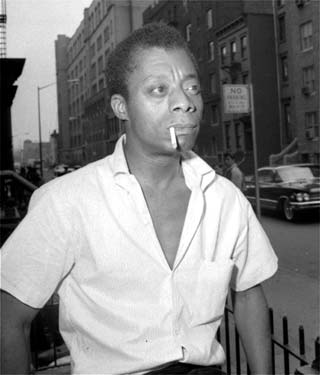

NPR’s Morning Edition featured James Baldwin today as part of their continuing “American Lives” series. Listen and read here. Their lede–

The writer James Baldwin once made a scathing comment about his fellow Americans: “It is astonishing that in a country so devoted to the individual, so many people should be afraid to speak.”

As an openly gay, African-American writer living through the battle for civil rights, Baldwin had reason to be afraid — and yet, he wasn’t. A television interviewer once asked Baldwin to describe the challenges he faced starting his career as “a black, impoverished homosexual,” to which Baldwin laughed and replied: “I thought I’d hit the jackpot.”

In the piece, NPR talks with Randall Kenan, editor of a new collection of Baldwin’s essays, speeches, and articles called The Cross of Redemption. The link above includes a great excerpt of one of Baldwin’s essays, “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare.” A taste–

The greatest poet in the English language found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people. He could have done this only through love — by knowing, which is not the same thing as understanding, that whatever was happening to anyone was happening to him. It is said that his time was easier than ours, but I doubt it — no time can be easy if one is living through it. I think it is simply that he walked his streets and saw them, and tried not to lie about what he saw: his public streets and his private streets, which are always so mysteriously and inexorably connected; but he trusted that connection. And, though I, and many of us, have bitterly bewailed (and will again) the lot of an American writer — to be part of a people who have ears to hear and hear not, who have eyes to see and see not — I am sure that Shakespeare did the same. Only, he saw, as I think we must, that the people who produce the poet are not responsible to him: he is responsible to them.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden, Helen Grant’s debut novel, negotiates the razor’s edge between childhood’s rich fantasy world and the grim reality of adult life. When young girls start disappearing in her small German village, eleven year old protagonist Pia sets out to investigate, armed with her powers of imagination–an imagination fueled by the Grimmish tales spun by her elderly friend Herr Schiller for the pleasure of Pia and her only friend, StinkStefan. Like poor Stefan, Pia is ostracized by the town after her grandmother spontaneously combusts on Christmas. She takes to playing detective, but as she investigates the girls’ disappearances, the illusions of her fantasy life cannot protect her. As the story builds to its sinister climax, it reminds us that most of the folktales we grew up with are far darker than we tend to remember.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden, Helen Grant’s debut novel, negotiates the razor’s edge between childhood’s rich fantasy world and the grim reality of adult life. When young girls start disappearing in her small German village, eleven year old protagonist Pia sets out to investigate, armed with her powers of imagination–an imagination fueled by the Grimmish tales spun by her elderly friend Herr Schiller for the pleasure of Pia and her only friend, StinkStefan. Like poor Stefan, Pia is ostracized by the town after her grandmother spontaneously combusts on Christmas. She takes to playing detective, but as she investigates the girls’ disappearances, the illusions of her fantasy life cannot protect her. As the story builds to its sinister climax, it reminds us that most of the folktales we grew up with are far darker than we tend to remember.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden makes its American debut this month from Delacorte Press.

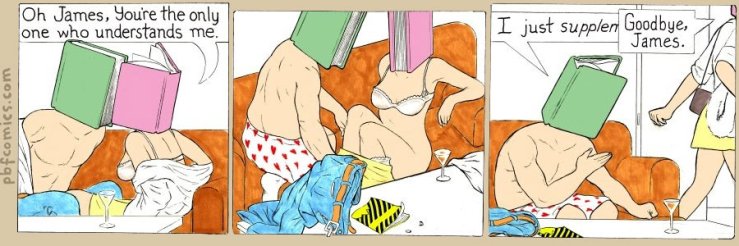

“Hard Read,” from the geniuses at The Perry Bible Fellowship.

“Hard Read,” from the geniuses at The Perry Bible Fellowship.

Apocalypse literature, when done right, can inform us about our own contemporary society. It can satirize our values; it can thrill us; it can astound us with its sheer uncanniness. I’m thinking of Russell Hoban’s Ridley Walker, Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novels, Cormac McCarthy’s novels Blood Meridian (yeah, Blood Meridian is an end-of-the-world novel) and The Road, Aldous Huxley’s Ape and Essence and Brave New World. There are many more of course–hell, even the Bible is bookended by the apocalypse of the flood (and Noah’s escape) and the Revelation to John. Then there are the movies, too many to name in full at this point (China Miéville even called for a “breather” a while back), but the ones that work become indelible touchstones in our culture (George Romero’s zombie films and Children of Men spring immediately to mind).

So, my interest in such works foregrounded, perhaps I should get to the business of reviewing Justin Cronin’s massive virus-vampire apocalypse saga/blatant money-making venture The Passage. But before I do, let me get anecdotal: earlier this summer, because of my aforementioned interest in apocalypse lit I tried to listen to the unabridged audiobook version of Stephen King’s The Stand. I bring this up here because Cronin’s book is utterly derivative of The Stand. I also bring it up because I had the good sense to quit The Stand almost exactly half way through–good sense I did not extend to The Passage. Yes, dear reader, I listened to the whole damn audiobook, all 37 hours of it. It helped that I had a home renovation project going that took up most of this week. So I listened to Cronin’s dreadful prose, hacky twists, and derivative plots while sanding joint compound and painting for eight hours at a stretch. True, it’s a much easier audiobook to follow than, say, something by Dostoevsky–but that’s only because anyone with a working knowledge of apocalypse tropes has already seen and heard it all before.

So what is it? In The Passage a government virus turns people into vampire-like zombies with hive mines. There’s a mystical little girl at the center of it all. Does she hold the key to mankind’s salvation? Does all of this sound terribly familiar? Cronin’s book begins in the not-too-distant future, tracing the origins of the virus that will unleash doom and gloom; then, about a third of the way in, he skips ahead about a 100 years to explore what life is like for the survivors. While the commercial prose had taxed me about as far as I could go, I have to admit that this twist a third of the way in intrigued me–what would life be like for these folks? What savagery did the “virals” (also called “smokes,” “dracs,” and a few other names I can’t remember) unleash? Luckily, there’s plenty of exposition, exposition, exposition! Cronin saturates the second part of his novel with so much background information that he essentially ruins any chance the book has to breathe. There’s no mystery, no strangeness–just many, many derivative plots and creaky set-pieces thinly connected with enough chapter-ending cliffhangers to make Scheherazade blush. This wouldn’t be so bad if Cronin’s characters weren’t stock types that would seem more at home in an RPG than, I don’t know, a novel. It’s hard to care about them as it is, but as the novel progresses he frequently puts them in mortal peril and then saves them at the last-minute–again and again and again. The derivative nature of The Passage wouldn’t smart so much if the characters weren’t so flat and the prose so mundane. The action scenes are fine–just fine–but when Cronin gets around to like, expressing themes and ideas the results are risible. It’s like the worst of Battlestar Galactica (you know, those last three seasons), maudlin soap opera that tips into mushy metaphysics.

But I fear I’ve broken John Updike’s foremost rule for reviewing books — “Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.” I think that Cronin has set out to make money here, and he’s written the type of book that will do that, the kind of book that will make some (many) people think that they are reading some kind of intellectual alternative to those Twilight books. There will be sequels and there will be movies and there will be lots and lots of money, enough for Cronin to swim in probably, if he wishes. In the meantime, go ahead and skip The Passage.

Great series of tweets today from Roger Ebert about e-books. Here’s what he’s done so far–

Here’s my old e-book “10,000 Jokes, Toasts and Stories,” and written inside “To my boy Roger from Daddy.”

Look at this theater ticket stub I found! I used it in an old e-book, from Stratford-upon-Avon.

Needed: New Yorker cover showing Dr. Johnson in his library, a cup of tea at hand, with shelves and piles of his e-books.

I found this e-book on a top shelf of a used e-book store. Its cover somehow reached out to me.

I love to relax in my library and let my eyes stray over my e-books, each one triggering its own response.

We only met in the first place because she spotted the cover of the e-book I was reading across the aisle on the train.

Great stuff!

Time profiles Jonathan Franzen this week (part of the push for his new novel Freedom, out later this month). Franzen also talks about five works that have “inspired him recently.” Here are his comments on those books–

Time profiles Jonathan Franzen this week (part of the push for his new novel Freedom, out later this month). Franzen also talks about five works that have “inspired him recently.” Here are his comments on those books–

The Charterhouse of Parma by Stendhal

Instead of sitting for years at his writing desk, pulling his hair, Stendhal served with the French diplomatic corps in his favorite country, Italy, and then came home and dictated his novel in less than eight weeks: what a great model for how to be a writer and still have some kind of life! The book is at once deeply cynical and hopelessly romantic, all about politics but also all about love, and just about impossible to put down.

The Greenlanders by Jane Smiley

There’s nothing fancy about the writing in Smiley’s masterpiece, and yet every sentence of its eight hundred pages is clean and necessary. For the two weeks it took me to read it, I didn’t want to be anywhere else but in late-medieval Greenland, following the passions and feuds and farming crises of European settlers trying to survive in the face of ecological doom. It all felt weirdly and plausibly contemporary.

Sabbath’s Theater by Philip RothI finally got tired of being angry at Roth for his self-indulgent excesses and weak dialogue and thin female characters and decided to open myself to his genius for invention and his heroic lack of shame. Whole chunks of Sabbath’s Theater can be safely skipped, but the great stuff is truly great: the scene in which Mickey Sabbath panhandles on the New York with a paper coffee cup, for example, or the scene in which Sabbath’s best friend catches him relaxing in the bathtub and fondling his (the friend’s) young daughter’s underpants.

The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

Wharton’s male characters suffer from some of the deficiencies that Roth’s female characters do, but the heroine of House of Mirth, Lily Bart, is one of the great characters in American literature, a pretty and smart but impecunious New York society woman who can’t quite pull the trigger on marrying for money. Wharton’s love for Lily is equal to the cruelty that Wharton’s story relentlessly inflicts on her; and so we recognize our entire selves in her.

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

A lifelong heavy drinker with his most famous novel well behind him, Steinbeck set out to write a mythic version of his family’s American experience that would embody the whole story of our country’s lost innocence and possible redemption. There are infelicities on almost every page, and the fact that the book succeeds brilliantly anyway is a testament to the power of Steinbeck’s storytelling: to his ferocious will to make sense of his life and his country.

In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from Columbia University Press.

In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from Columbia University Press.

All My Friends Are Dead by Avery Monsen and Jory John. From Chronicle Books.

All My Friends Are Dead by Avery Monsen and Jory John. From Chronicle Books.

Spanish-language blog La fortaleza de la soledad has republished The Paris Review’s interview with Jonathan Lethem. Cool interview–Lethem talks about his hippie parents, going to school with Bret Easton Ellis, explains why William Gibson is the new Thomas Pynchon, and discusses his novels at length. From the interview —

I felt I ought to thrive on my fate as an outsider. Being a paperback writer was meant to be part of that. I really, genuinely wanted to be published in shabby pocket-sized editions and be neglected—and then discovered and vindicated when I was fifty. To honor, by doing so, Charles Willeford and Philip K. Dick and Patricia Highsmith and Thomas Disch, these exiles within their own culture. I felt that was the only honorable path.

“Thomas Pynchon: Man of Mystery” — Comic by Kelly Shane & Woody Compton, part of their Is This Tomorrow? series.

The Guardian profiles Don DeLillo. The profile is pretty silly, referring to DeLillo as an “All-American writer,” and mistakenly referring to his 2007 novel Falling Man as The Falling Man (this reminds me of the way that grandparents love to add a definite article to pretty much anything, e.g. “I have to go to the Wal-Marts”). Here it is —

After Underworld, an 800-page tour de force, DeLillo’s career turned towards the miniature: The Body Artist (2001), Cosmopolis (2003), The Falling Man (2007) are much slighter books, a rallentando that suggests a writer moving inexorably into the minor key of old age. Not that you’d find this in the demeanour of DeLillo.

The writer makes up for the error by using the word “rallentando,” of course.

(Thanks to A Piece of Monologue for directing our attention this way).