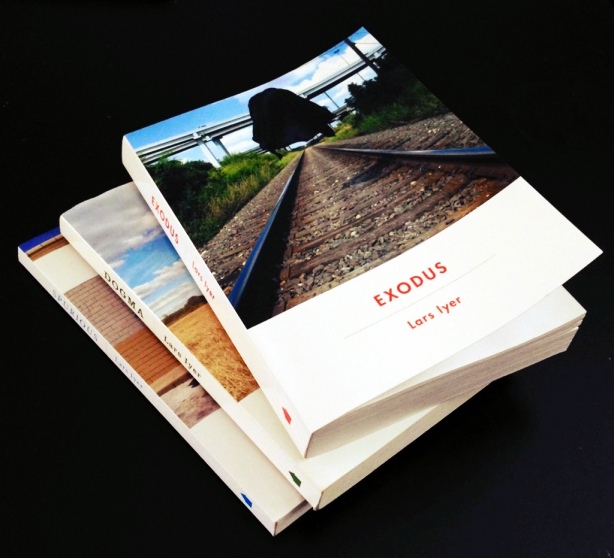

I. Trilogy

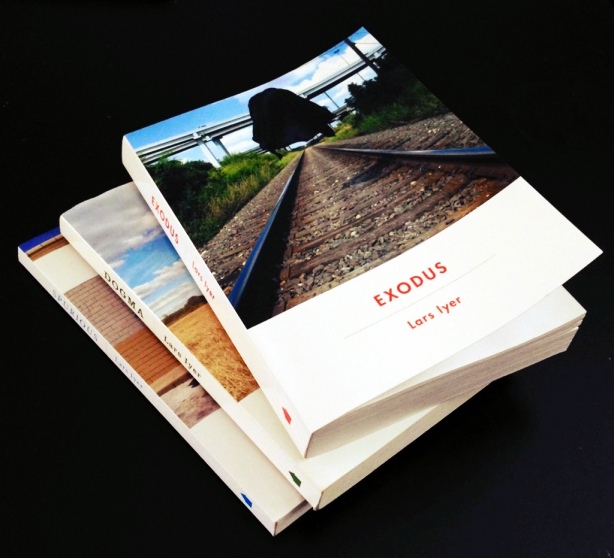

Exodus is the third entry in a trilogy that Lars Iyer began with Spurious and Dogma.

What happens in Exodus?

Not much (but also maybe everything—like all sorts of philosophical investigations and intellectual adventure and despair and potential revolution and symbolic death, etc.).

If you’ve read Spurious and Dogma you’d expect this.

There is a quest though in Exodus, a quest that feels more visceral, more real, cuts closer to the bone than in the first two entries.

What is this quest?

Do our heroes W. and Lars vanquish despair? Figure out Kafka?

Do they save humanity (or at least the humanities department)?

Do they finally cast the One Ring into Mount Doom?

(They go on a lecture tour).

II. Quest

What is the connection between Kierkegaard and capitalism?: that’s our question, W. says. What does Kierkegaard tell us about the despair of capitalism?

And

‘The true and only virtue is to hate ourselves’, W. says, reading from his notebook.

And, perhaps more specifically

Of course, they’re going to close all humanities courses in British universities, W. says . . . They’re simply going to marketise education, W. says. They’re simply going to turn the university over to the free market. They’re going to submit philosophy to the forces of capitalism . . .

And

Imagine it! Two plastic cups of Plymouth Gin might usher in the reign of peace, W. says.

And

There are no jobs in philosophy — everyone knows that. No jobs in academia!

And etc.

III. The Call to Adventure

This is our last tour, W. says. He feels that strongly. Something’s going to happen. Something’s about to happen. . . Why does he feel such a sense of dread?

IV. The Road of Trials

Gin, Deleuze, Kafka, Kierkegaard, gin, Blade Runner, Guy Debord, postgraduate students, linguistic stupidity, anxiety over what Alan Badiou is doing right this very minute, gin, Gandhi, Marx, the blogosphere (so-called), Bartleby, Moses, God, logical-mathematical stupidity, the Talmud, gin, bodily-kinesthetic stupidity, cheap food, the Thames, Oxford, Rosenzweig, interpersonal stupidity, gin, Bela Tarr, Manchester, Wikipedia, gin, intrapersonal stupidity, Beckett, Gombrowicz, Middlesex, Weil, naturalistic stupidity, Abraham and Isaac, Old Europe, sports science students, moral stupidity, Solomon Maimon, gin, Plato (turning in his grave), public houses, existential stupidity, Kant, a friend from Taiwan, a plenary speaker, sartorial stupidity, gin, Krasznahorkai, blowing a great horn to have the horde come running (like that guy in Anchorman), a Dostoevskian innocence or a Grossmanian selflessness, religious stupidity, Master/Blaster as a metaphor for the mind-brain problem, Canadian laughter in the glittering light (etc.), Essex Postgraduates, gin, gin, gin, job security, painting-and-decorating stupidity, hangovers, posh people eating lunch in the sun, settling for cans of Stella from the trolley, philosophy of walking, gin, romantic stupidity, gin, culinary stupidity, gin, stupidity stupidity.

Revolution!

V. The Magic Flight

Alcohol makes people speak, that’s its greatness, W. says. It makes them religious, political, even as it shows them the impossibility of religion and the impossibility of politics. Drinking carries you through despair, W. says. Through it, and out beyond it, if you are prepared to keep drinking right all through the night.

VI. Apotheosis

W. dreams of the profound slumber from which we would rise reborn, ready for the morning, ready for work. He dreams of the great day that would follow our night of rest, and of the great ideas that would flash above us like diurnal stars.

How is it still alive in him, the belief that he might wake into genius?, W says. How is it that he still believes, despite everything, that he is a man of thought?

VII. Freedom to Live

Thought is the hangman, our hangman, W. says. Thought has its nooses ready just for us.

VIII. Cult Fiction

Judgment, evaluation, criticism: Exodus—the Spurious Trilogy, if that’s what we’ll call it—has reserved its own special place in the world of cult fiction. These novels (if they are in fact novels) perform their own deconstruction. They delineate metacognition. They frustrate. They are simultaneously sad and funny, and even a little bit scary, at least if you earn your bread by academicizin’.

They frustrate. Wait, do I repeat myself? Very well then, I repeat myself.

These novels dissect the problems of philosophy against the backdrop of late capitalism, but part of this dissection is also the covering up of the dissection: the fear, the failure, the despair, the doom. (Hence the anesthesia, the gin). So that the novels seem to be a series of references, contours, quirks, loops of dialog, declamations, insults . . . That the novels take their own central subject as the failure to mean, to communicate—and then perform these failures: deferral, delay, intellectual suspense. And that these suspensions replace the furniture and sets of the traditional novel, etc. Maybe I’m failing to mean. I’ve anesthetized myself a bit, I do admit.

I get it. I mean, that’s maybe what I mean, or hope to mean to say about these novels: That meaning is hard, that saying meaning doing thinking is hard; that thinking after, against, beyond other thinkers is hard, painful, produces despair, dread, etc. Maybe that’s why I like these novels. Because I think that maybe I get them even as I doubt that I do get them.

IX. An Idea

Publisher Melville House might consider putting all three of these books into one epic volume.

X. A Question

Do the eagles ever show up to fly W. and Lars out of Mordor?