“Thomas Pynchon: Man of Mystery” — Comic by Kelly Shane & Woody Compton, part of their Is This Tomorrow? series.

“Thomas Pynchon: Man of Mystery” — Comic by Kelly Shane & Woody Compton, part of their Is This Tomorrow? series.

The Guardian profiles Don DeLillo. The profile is pretty silly, referring to DeLillo as an “All-American writer,” and mistakenly referring to his 2007 novel Falling Man as The Falling Man (this reminds me of the way that grandparents love to add a definite article to pretty much anything, e.g. “I have to go to the Wal-Marts”). Here it is —

After Underworld, an 800-page tour de force, DeLillo’s career turned towards the miniature: The Body Artist (2001), Cosmopolis (2003), The Falling Man (2007) are much slighter books, a rallentando that suggests a writer moving inexorably into the minor key of old age. Not that you’d find this in the demeanour of DeLillo.

The writer makes up for the error by using the word “rallentando,” of course.

(Thanks to A Piece of Monologue for directing our attention this way).

James Jean does Thomas Pynchon. (Via Hey Oscar Wilde!).

At Jezebel, a list of drinking games for readers. Some witty, some not so witty. Here’s the list:

Thomas Pynchon: Drink every time someone has a stupid name, like “Eigenvalue.”

David Foster Wallace: Drink every time a sentence has three or more conjunctions.

William Faulkner: Every time a sentence goes on for more than a page, drink the entire bottle. Then make out with your sister.Joyce Carol Oates: Drink every time there is a home invasion.

Jane Austen: Drink every time someone plays whist, goes riding, or gets married.

J.D. Salinger: Every time there is a symbol of lost innocence, drink a highball. Then spit it all over someone you love.

Emily Bronte: Drink every time you see the word “heath” (Heathcliff counts).

Gabriel García Márquez: Drink every time someone’s name is “Aureliano.” (Note: this only works for A Hundred Years of Solitude)Virginia Woolf: First, go buy some flowers. Then, if you have time left over, drink.

Sappho: Drink every time you can’t tell if something is hot or disgusting.

Ernest Hemingway: Drink every time Ernest Hemingway is boring and overrated. Man, I am so wasted right now.

Raymond Chandler: Drink every time someone drinks.

Dashiell Hammett: Drink every time someone drinks.

Homer: Drink every time someone drinks gross diluted wine.Stephenie Meyer: Drink every time someone drinks blood.

Dylan Thomas: Drink until you are in a coma.

I think you can apply the rules for the Chandler and Hammett games to Bukowski if you wanted. Use Kingsley Amis’s signature cocktail the Lucky Jim if you wish. You might also be interested in David Foster Wallace’s drinking game “Hi Bob.”

The Paris Review interviews David Mitchell in their new issue. An excerpt from their free excerpt:

INTERVIEWER I noticed this sentence in Number9Dream: “The cloud atlas turns its pages over.”

MITCHELL Wow, is that in Number9Dream? Then the phrase was haunting me earlier than I realized. “Cloud Atlas” is the name of a piece of music by the Japanese composer Toshi Ichiyanagi, who was Yoko Ono’s first husband. I bought the CD just because of that track’s beautiful title. It pleases me that Number9Dream is named after a piece of music by Yoko’s more famous husband, though I couldn’t duplicate the pattern indefinitely.

INTERVIEWER The epigraph to Number9Dream is from Don DeLillo: “It is so much simpler to bury reality than it is to dispose of dreams.”

MITCHELL The best line in the book and it’s not even mine.

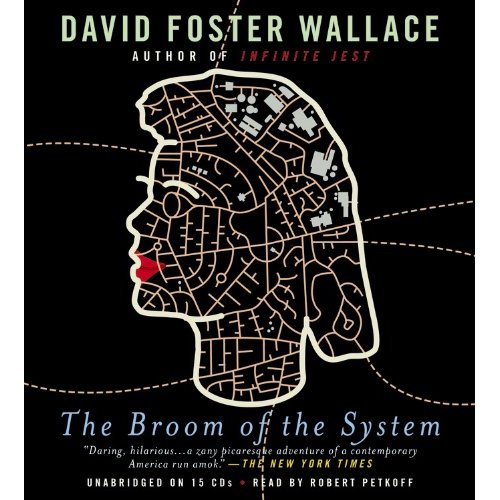

In David Foster Wallace’s first novel The Broom of the System, protagonist Lenore Beadsman’s brother and his friends play a drinking game based on The Bob Newhart Show. Here are the rules–

On television was ”The Bob Newhart Show.” In the big social room with LaVache were three boys who all seemed to look precisely alike. . . . ”Lenore, this is Cat, this is Heat, this is the Breather,” LaVache said from his chair in front of the television. . . .

Heat and the Breather were on a spring-sprung sofa, sharing what was obviously a joint. Cat was on the floor, sitting, a bottle of vodka before him, and he clutched it with his bare toes, staring anxiously at the television screen.

”Hi Bob,” Suzanne Pleshette said to Bob Newhart on the screen. . . . La Vache looked up from his clipboard at Lenore. ”We’re playing Hi Bob. You want to play Hi Bob with us?” He spoke sort of slowly. Lenore made a place to sit on the luggage. ”What’s Hi Bob?” The Breather grinned at her from the sofa, where he now held the bottle of vodka. ”Hi Bob is where, when somebody on ‘The Bob Newhart Show’ says ‘Hi Bob,’ you have to take a drink.”

”And but if Bill Dailey says ‘Hi Bob,’ ” said Cat, tending to the joint with a wet finger, ”that is to say, if the character Howard Borden on the show says ‘Hi Bob,’ it’s death, you have to chug the whole bottle.”

”Hi Bob,” said Bill Dailey on the screen.

This text was originally cited in Caryn James’s 1987 review of The Broom of the System in The New York Times. Here’s our review.

David Foster Wallace’s first novel The Broom of the System obsesses over language, words, storytelling and what it might mean to have our lives circumscribed in another person’s narrative. Hatchette Audio’s new audiobook version of Broom highlights the strength of Wallace’s dialogue, a feature of his writing perhaps overlooked, or at least overshadowed, by his complex diction and syntax and his innovative narrative structures. The Broom audiobook features the considerable talents of reader Robert Petkoff, who brings life to its many characters like protagonist Lenore Stonecipher Beadsman, a switchboard operator looking for her grandmother (and namesake) in the weird nooks and crannies of Wallace’s fictional Cleveland. Gramma Lenore (grammar Lenore; lost Lenore) is a former pupil of Wittgenstein, a conceit that allows Wallace to run wild with his own philosophical-linguistic concerns. I first read Broom as an undergrad–this was almost 15 years ago now–and I was pretty soaked in post-structuralist philosophy at the time, at least enough to think I was getting what many of Wallace’s mouthpieces were saying. There’s an obsession with Self and Other and whatever membrane might keep them separate; there’s the paranoia that language dictates our lives; there’s a sense that the postindustrial landscape has led to the need to engender new means of communion. Politicians create the Great Ohio Desert–or G.O.D. (subtle, I know) as a place for spiritual quests; psychiatrists prescribe bizarre ritual theaters for families to produce in front of a recording of a TV audience; a drugged bird develops speech abilities and is mistaken for a miracle. Broom is a dizzying satire of modernity, or more properly, postmodernity (the book was first published in 1987 but set in 1990).

Journeying through the book years later is a new experience, especially in light of how much Wallace and his literary followers have remapped the terrain of fiction. Many of Broom‘s experimental innovations, like the incorporation of TV transcripts, scholarly articles, medical documents, and other “found footage” are so normalized in contemporary fiction as to be almost clichéd in 2010. While these moments are never glaring or gauche in Broom, their inclusion lacks the finesse that Wallace would later demonstrate in Infinite Jest. Similarly, Wallace’s characters in Broom are too cartoonish to connect with. Read aloud, their punning names become a cavalcade of groans:Wang-Dang Lang, Peter Abbott, Candy Mandible, Judith Prietht, Biff Diggerance, and so on, as if Wallace can’t help himself. The Pynchonesque goofiness gets in the way of the reader-writer relationship that Wallace ultimately wants, the Wittgensteinian language game that would allow for identification beyond words. Purposeful bathos is still bathos. Lenore is an engaging character but, as she frequently worries and suspects, she is just that, a character, never transcending the page like Don Gately of Infinite Jest. But it’s cruel and stupid to fault Broom for not being Infinite Jest, especially when Broom is such a rewarding novel. Published when Wallace was just 24, it shows the grand strains of First Novel Syndrome, of a genius trying to push out too many ideas, too many characters, too many philosophical riffs at once. While Infinite Jest is hardly restrained, it shows Wallace’s powerful control over Too Much; it converts Too Much into Not Enough, into Give Me More.

The highlight of Broom is in its storytelling, in its capacity to explode clichés and expose the truth and energy stored within them. Rick Vigorous, Lenore’s would-be beau with literary aspirations, repeatedly shares stories with Lenore (and us, of course). They can be silly and maudlin and mawkish and downright awful, but also inspiring and sad and horrific, all at the same time, and Wallace engineers and comments on these stories (and the other stories that populate the book) in a way that somehow breaks with or goes past the postmodern tradition he’s otherwise relatively beholden to in Broom. And while Wallace’s first novel never achieves the exquisite sadness of Infinite Jest (although it would clearly like to), it does share the same rap-session humor, the same intimate narrative voice that welcomes the reader to laugh, to ponder, to play the game. Recommended.

Tom McCarthy’s marvelous, confounding new novel C tells the life story of Serge Carrefax and his strange adventures at the beginning of the twentieth century. The novel begins with Serge’s birth on his parents’ estate Versoie; he’s born with a caul, a “veil around his head: a kind of web,” a mystic mark that both disconnects and, paradoxically, joins him to the world. At Versoie, Serge’s father Simeon experiments with wireless technology and runs a school for deaf children while Serge’s deaf mother farms bombyx mori moths for silk. Serge and big sis Sophie are left to the care of their tutor Mr. Clair, but they manage to get into trouble with their chemistry set when he’s not looking. In addition to offering the Carrefax kids a classical education, Mr. Clair, a proto-Marxist, teaches them a game akin to Monopoly. In a particularly inspired scene, they soon dispense with the game board to recreate the game on the real-live grounds of Versoie, eventually incorporating the aid of a wireless communication system. Then, when moving from wireless receiver to wireless receiver becomes too much hassle, they simply co-ordinate the game in their collective imagination, managing properties in the pure abstract. The game elegantly emphasizes the siblings’ development from playing via symbolic representation, to enacting those symbols on a one-to-one scale, to finally internalizing and encapsulating the real world. It’s as if they’ve swallowed Versoie into their very beings.

Versoie initiates and enacts its own strange culture and mythology, one that intertwines inextricably with Serge and Sophie’s childhood. It’s a rich, detailed world, at once magical and unsettling, bustling with bizarre pageants (part of Simeon’s curriculum), eclectic experiments, and visitors like Widsun, a British intelligence code-breaker/code-maker who serves as a mentor first to Sophie and later Serge. While Sophie delights in secret codes and chemistry (particularly poison-making), Serge experiments with wireless technology, spending late nights on his homemade wireless set with other “bugs.” In one scene, Serge listens to “an RXer in Lydium who calls himself ‘Wireworm’ [who] is tapping out his thoughts about the Postmaster General’s plans to charge one guinea per station for all amateurs.” Tech geeks with hyperbolic handles griping over minutiae in the wee hours–sound familiar? McCarthy describes Serge’s reaction: “Transcribing his clicks, Serge senses that Wireworm’s not so young: no operator under twenty would bother to tap out the whole word ‘fashion.’ The spacing’s a little awkward also: too studied, too self-conscious.” We get text messaging a century before text messaging, and as Serge searches between news reports and chess games and distress calls, we see that the world wide web is far older than we might have thought. Later in the novel Simeon writes a letter to his son where he describes a proto-internet, claiming his ambition is “to transmit moving pictures over distance, such that life in all its full, vibrant immediacy may be relayed without any delay.” This isn’t steampunk though, it’s simply a reminder that wireless technology isn’t an invention of our own time. C is an historical fiction deeply concerned with technological fact. It’s also a bildungsroman, too, so let’s return to young Serge, who soon ventures to a Bohemian spa with Clair as chaperon.

The adolescent Serge is ill. He perceives the world through a “guazy crepe” that blackens his vision, recalling the amniotic sac that webbed his head at birth. At the spa, Dr. Philip diagnoses Serge’s problem: “You . . . have got blockage. Jam, block, stuck. Instead of transformation, only repetition.” He accuses Serge of enjoying his illness, of enjoying “to feast on the mela chole, on the morbid matter, and to feast on it repeatedly, again, again, again, like it was lovely meat–lovely, black rotten meat.” The Burroughsian image of black meat pops up again and again in C, perhaps suggesting the human limitation to transcend–or in Philip’s words, transform–the mortal condition. However, Serge manages, through his own devices, to break through the blockage; if his epiphany is ultimately negative, at least it is real, a semi-Cronenbergian sexual awakening with a hunchback.

Like Versoie, the Bohemian spa is both a rich and alienating setting; McCarthy’s great gift to the reader is crafting enough detail in his set pieces to make them seem utterly real, yet to withhold enough so that the reader’s imagination fills in the gaps that might exist outside of Serge’s proximity. C is only 300 pages long yet feels much deeper–not longer, but deeper. This is most evident in the novel’s next milieu, the Great War, where Serge serves as a Royal Air Force aerial observer. War novels, histories, and movies have given us so much information about WWI that it would be easy for McCarthy to rely on stock tropes and received wisdom in communicating his set-piece, but instead he gives us something startlingly new. For example, how were the drugs in WWI, McCarthy asks. It’s in the Air Force that Serge first uses cocaine, rubbing it into his retinas to improve his eyesight while he’s spotting for German artillery batteries. He quickly moves to snorting mounds of the stuff before each take off. Here’s a lovely passage, where we see Serge’s nascent addiction blurring his perspective, ultimately leading to an autoerotic climax–

Higher up, the vapour trails of the SE5s form straight white lines against the blue, as though the sky’s surface were a mirror too. Scorch-marks and crater contours on the ground look powdery; it seems that if he swooped above them low enough, then he could breathe them up as well, snort the whole landscape into his head. The three hours pass in minutes. As they dip low to strafe the trenches on the way back, he feels the blood rush to his groin. He whips his belt off, leaps bolt upright and has barely got his trousers down before the seed shoots from him, arcs over the machine’s tail and falls in a fine thread towards the slit earth down below.

“From all the Cs!” he shouts. “The bird of Heaven!”

Serge doesn’t bother to reflect much on this episode and McCarthy’s third-person narrator is so effaced in the novel as to seem almost invisible. McCarthy shows and never tells, even when he allows some insight into Serge’s psyche. We learn that–

Of all the pilots and observers, Serge alone remains unhaunted by the prospect of a fiery airborne end. He’s not unaware of it: just unbothered. The idea that his flesh could melt and fuse with the machine parts pleases him. When they sing their song about taking cylinders out of of kidneys, he imagines the process playing itself out backwards: brain and connecting rod merging to form one, ultra-intelligent organ, his back quivering in pleasure as pumps and pistons plunge into it, heart and liver being spliced with valve and filter to create a whole new, streamlined mechanism.

Serge’s indifference toward death (or life) and his frequent drug-use aren’t the manifestations of a death-wish–although C does pull its hero to a mortal end, as a bildungsroman should–rather, we see in Serge’s cyborg fantasy a wish for transhumanist transcendence. Serge’s job as a flying observer grants him some measure of transcendence, reducing the landscape to a flat two-dimensional perspective that he can easily process and read. At the same time, the novel tropes against the motif of two-dimensional perspective, repeatedly pushing Serge into interior excavations, like a worm or beetle digging in to the earth. This happens in the most literal sense at the end of the Great War, when the Germans capture Serge and hold him as a P.O.W. Serge is fine though, happy to tunnel underground (as long as his morphine hookup remains unimpeded).

Serge’s drug addiction continues into his postwar years in London. Nominally an architecture student, he spends most of his time scoring heroin and coke and partying with would-be actresses. Serge’s inclination to two-dimensional perspective inhibits his architectural aptitude. He can only plan tombs. McCarthy’s evocation of 1920s London is dark and strange, a drug-addled fever dream riddled with ciphers and ghosts. The set-piece comes to a head when Serge’s girlfriend takes him to see a psychic medium who purports to channel the spirits of those who died in the war. An enraged Serge uses wireless technology to reveal the scam, but puncturing the fantasy effectively brings an end to his relationship.

Serge soon reconnects with his father’s friend Wisdun, who sends the young man to Egypt. Serge’s mission is to scout sites for the wireless pylons that will unite the world, but he’d really rather puzzle out the cultural, historical, and linguistic mishmash of Alexandria and explore unopened tombs in the desert with an archeologist’s sexy assistant. I’ve perhaps revealed too much of the book’s plot so far, and while I think I’ve avoided spoilers, I’ll hope that you simply take my word that the Egyptian set-piece at the end of C is a masterful, disturbing climax to a rich and rewarding book. C culminates by tying together its central juxtapositions of sex and death, connection and disconnection, excavation and total, flat perspective with its many motifs: bugs, tombs, art, drugs, language, time, communication, spirit. The book’s final pages are stunning; it’s the kind of linguistic storm that demands immediate rereading.

And you’ll want to reread the book: McCarthy gives us so much to unpack. There’s that enigmatic title, of course. What is the “C” in C for? C is for Carrefax, of course, but that’s too obvious. In his blurb, Luc Sante rightly points out that “C is for carbon and cocaine, Cairo and CQ.” I might also add that C is for see and sí and sea; C is for call and caul; C is for communicate and communion; C is for the c that slips from “insect” to “incest.” (I could go on of course; a third reading of the book will undoubtedly yield more). C seems to call to Thomas Pynchon’s V., a novel littered with historical episodes that dances with a bildungsroman’s structure. C also calls to Voltaire’s satirical bildungsroman Candide. And while I’m lazily name-dropping authors and books, I might as well favorably compare C with Joyce’s Portrait and much of J.G. Ballard and William Burroughs. It’s also thoroughly soaked in Freud and continental philosophy.

C is the best novel I’ve read in a long time, and the first novel I’ve immediately reread in full in a very long time. It will leave many readers cold (or even disgusted, perhaps), but isn’t this always the way for writers who push their audience? (Consider my lazy name-dropping above). You probably know by now if this is for you, but if I haven’t been clear — very highly recommended.

C is available in hardback in the UK on August 5, 2010 from Jonathan Cape, and available in hardback in the US on September 7, 2010 from Random House.

The Guardian published a great profile of Tom McCarthy today. Topics include Freud, the avant-garde, archeology, and his forthcoming novel C. From the article, here’s McCarthy on his book’s setting:

The Guardian published a great profile of Tom McCarthy today. Topics include Freud, the avant-garde, archeology, and his forthcoming novel C. From the article, here’s McCarthy on his book’s setting:

“It’s the great period of emergent technology,” McCarthy explains. “The book is set between 1898 – when Marconi was doing some of his earliest experiments – and 1922, which is the year the BBC was founded, and also the great year of modernism: The Waste Land and Ulysses. I wanted C to be a kind of archaeology of literature. But I think all ‘proper’ literature always has been an archaeology of other literature. The task for contemporary literature is to deal with the legacy of modernism. I’m not trying to be modernist, but to navigate the wreckage of that project.”

The Guardian has also run a review of C. Biblioklept’s review runs tomorrow. It was a struggle to write–it’s always a struggle to review a book you absolutely love. You always end up sounding a bit too breathless.

In Hilary Mantel’s 2005 novel Beyond Black, a fat psychic named Alison endures the harrowing torment of a collective of ghosts she calls the Fiends, the spirits of cruel men from her childhood. When a young, aimless woman named Colette comes into Alison’s life and assumes managerial duties for her career, Alison’s bilious past comes to a head. Colette engineers more and better gigs for Alison (the death of Princess Diana causes a huge spike in business), who, despite her genuine psychic talents, must nonetheless run the kind of scam the “punters” in her audience crave. Colette and Alison soon move in together, buying a new house in a quiet, boring suburb outside of London; their prefab homestead is drawn in sharp contrast to the slums of Aldershot where Alison grew up–the novel’s second setting. As Beyond Black progresses, contemporary suburban Britain increasingly crumbles into Alison’s grim, greasy past in Aldershot. Alison’s chief tormentor is, ironically, her “spirit guide,” a mean little man named Morris, a one-time frequent customer for Alison’s prostitute mother. Alison, like many victims, has suppressed much of her grotesque childhood, but it’s hard to black out everything with psychic baggage like Morris weighing her down. In time, more and more of the Fiends reemerge, forcing Alison to confront her mother and the abuse they both suffered at the hands of those awful men. As the book lurches to its chilling climax, Alison asserts independence, casting out her metaphysical and psychological demons.

At its core, Beyond Black asks what it means to be haunted and how one might survive an abusive past whole and intact. A slim specter of a character named Gloria floats through the book. The Fiends, whose vile antics are sometimes compared to a gypsy circus, have dismembered Gloria with the old saw trick. In Alison’s memory, pieces of Gloria are scattered around her childhood home, parceled out, fed to dogs, transported in boxes at midnight, hidden. Alison’s awful mother frequently alludes to Alison herself being “sawed up,” a metaphor that dances on the literal as we come to realize that the old drunk has pimped out her daughter repeatedly. Mantel’s novel investigates the return of the repressed, and although she gives us something like a happy ending, the book’s central thesis seems to be that pain cannot be abandoned or hidden, but only mitigated through direct confrontation.

The book’s humor does nothing to lighten its grim subject–if anything it exacerbates and confounds the darkness at the heart of Beyond Black. Mantel’s gift for dialogue fleshes out her characters (even the spectral ones), and while the book aims for a satirical tone at times, its characters are too richly drawn to be mere cutouts in a stage production. Mantel’s satire of contemporary English life is sharp and bleak; you laugh a little and then feel bad for laughing and a page later you’re horrified. It’s a successful book in that respect. It’s one real weakness is in the character of Colette, whose voice gives way to Alison’s past by the book’s end. This is actually no problem, as Colette’s narrative life is not nearly as interesting as Alison’s psychic traumas; Colette is, however, catalyst for the changes in Alison’s life. It would’ve been nice to see more resolution here, but I suppose Beyond Black hews closer to real life here, with all its messy loose ends.

I chose to read Beyond Black because I enjoyed Mantel’s recent Booker Prize winner Wolf Hall so much. The books have little in common other than being well-written and tightly paced, and I think that anyone who wanted more Mantel after an introduction via Wolf Hall would do right to pick up Beyond Black. Recommended. Beyond Black is available in trade paperback from Picador.

James Wood, writing about Virginia Woolf in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” (collected in The Broken Estate)–

James Wood, writing about Virginia Woolf in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” (collected in The Broken Estate)–

Woolf, I think, became a great critic, not simply a “great reviewer.” The Collected Essays, which are still being edited, is the most substantial body of criticism in English this century. They belong in the tradition of Johnson, Coleridge, Arnold, and Henry James. This is the tradition of poet-critics, until the modern era, when novelists like Woolf and James join it. That is, her essays and reviews are a writer’s criticism, written in the language of art, which is the language of metaphor. The writer-critic, or poet-critic, has a competitive proximity to the writers she discusses. The competition is registered verbally. The writer-critic is always showing a little plumage to the writer under discussion. If the writer-critic appears to generalize, it is because literature is what she does, and one is always generalizing about oneself.

Wood’s description of Woolf is really Wood’s description of Wood.

Great essay today at The Guardian from Tom McCarthy, author of Remainder and the the forthcoming, highly-anticipated C. McCarthy discusses technology, modernity, and literature, mulling over writers like Blake, Cervantes, Shelley, Joyce, and Ballard. He also talks about some of the research that went into C. From his essay:

C takes place, specifically, between 1898 and 1922. The dates aren’t accidental: they mark the period between Marconi’s early short-distance radio experiments and the founding of that centralised state broadcaster of entertainment, news and propaganda that we still know as the BBC. In 1922, Britain was erecting, in its colonial territory Egypt, the first long-distance pylons of its proposed imperial wireless chain – and as it went about this, it lost Egypt, which gained independence in February of that year. For ancient Egyptians, “pylons” were gateways to the underworld: these modern ones came to symbolise bereavement on a national scale. In November, also in Egypt, Howard Carter disinterred what would become the most famous family crypt of all time. 1922 was also modernism’s annus mirabilis, seeing the publication of The Waste Land, in which voices, dialogues and even weather reports drift in and out of audibility as its author-operator fiddles with his literary dial – and Ulysses, a huge textual switchboard in which the themes of death and media are plugged into each other time and again.

Look for our full review of C sometime next week.

Vanity Fair interviews David Mitchell about his new book The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. The interviewer mistakenly (I believe, anyway) thinks James Wood is joking in his New Yorker review when he wonders if the book is “post-postmodernist.” Mitchell’s answer sounds about right.

VF: James Wood in the New Yorker was describing your books and he jokingly came up with the phrase post-postmodernism. If there were such a thing as post-postmodern literature, what do you think that might be?

DM: Oddly enough, I’m not sure if novelists are the best people to ask whither-the-novel questions. For me, it’s a little like I’m a duckbilled platypus and I’m being asked a question about taxonomy. You won’t get much of an answer out of a platypus because they’re busy going about their business digging tunnels, catching fish, and having sex. You really have to ask a critic, or a taxonomist. I feel like I should have a pithy answer because I’m a novelist and you’re asking a question about the future of the novel, but the biggest question I ever get to is, “How can I make this damned book work?” I rarely ever put my head above the rampart and see where this big lumbering behemoth called global literature is going.

(Thanks to the Bored Bookseller for the tip).

Yesterday, lawyers in Zurich opened four anonymous safety deposit boxes supposedly containing original manuscripts, letters, and drawings by Franz Kafka. The question of who owns the literary cache has turned into something of an international debacle, with lawyers and judges jostling for control.

In appreciation of Kafka (and this whole cosmically-ironic fiasco), we direct you to audio clips of the PEN fellowship’s March 26, 1998 tribute, which featured, among others, E.L. Doctorow, Susan Sontag, Cynthia Ozick, and Paul Auster, reading from their own essays on Kafka, or the Czech’s work. The highlight is David Foster Wallace’s essay “A Series of Remarks on Kafka’s Funniness from Which Not Enough Has Been Removed.”

You can stream the tracks here. True biblioklepts can download them directly from here.

At some point, almost every character in David Mitchell’s new novel, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet tells a story. The book teems with storytellers and their stories, overflows with compact bildungsromans, wistful jeremiads, high adventures drawn in miniature, comic escapades, bizarre folk tales, and romantic myths, all pressed into the service of the book’s larger narrative, the story of Jacob de Zoet, a Dutchman in Shogunate era Japan. In 1799, the relative starting point for this massive novel, Japan limited economic trade with Europeans to the Dutch East India Company, who, with a few rare exceptions, were not permitted to touch Japanese soil. Instead, the Dutch were confined to the man-made isle of Dejima in the bay of Nagasaki. With its rich cultural mishmash, claustrophobic isolation, and strange hybrid nature, Dejima makes a fascinating platform for Mitchell’s tale.

Most reviews of Mitchell’s new book have squared it against his earlier novels, particularly his experimental opus Cloud Atlas (The Guardian‘s review even begins by asking “Does it matter what books a novelist has written before? Should readers need to know an author’s preceding works fully to grasp the new one?”). The reason for this is plain. By and large, Thousand Autumns is a conventional historical novel, a straightforward linear narrative that combines a forbidden love triangle story with elements of high adventure. There are good guys and bad guys, Enlightened thinkers and scheming crooks, warriors and spies, and even an evil monk who may or may not have supernatural powers. Thousand Autumns (like its main setting Dejima) is richly detailed but hermetically sealed; what leaks from that seal are its myriad stories, its capacity for storytelling. This effusion of stories also marks the novel, I believe, as something more than the conventional historical novel it is purported to be. Even more interesting though is the space the novel is occupying in a current literary debate–is The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet a postmodern novel or not? The rest of my review will discuss this issue, along with James Wood’s review at The New Yorker and Dave Eggers’s review at The New York Times. The simple answer, of course, is that it doesn’t matter whether the book is postmodern or something else–it’s a very good book, I enjoyed it very much, and you probably will too. I encourage you to read Wood’s precis, which I’ve excised here, and then pick up the book. Anyone else interested in the foolish minutiae of what may or may not make a book postmodern or post-postmodern or something else may wish to continue (or not).

Here’s James Wood, using Mitchell’s oeuvre to dither over the fact that “The serious literary novel is at an interesting moment of transition” —

If postmodernism came after modernism, what comes after postmodernism? For that is where we are. “Post-postmodernism” tends toward an infinite stutter. “After postmodernism” suggests a severance that has not occurred. We might settle for “late postmodernism,” a term that suggests the peculiar statelessness of contemporary fiction, which finds itself wandering—not unhappily—between tradition and novelty, realism and anti-realism, the mass audience and the élitist critic. Thus David Mitchell can follow a “postmodern” novel with a “traditional” comic bildungsroman, and then follow that with a conventional historical novel. It is hard to know whether this statelessness is difficult freedom or easy imprisonment, but the more ambitious contemporary fiction will often blend a bewildering variety of elements and historical techniques [. . .]

Dave Eggers, however, feels no need to look for machinations beyond straightforward storytelling. He claims that Thousand Autumns retains the

[. . .] narrative tendencies [of Mitchell’s earlier works] while abandoning the structural complexities often (and often wrongly) called postmodern. This new book is a straight-up, linear, third-person historical novel, an achingly romantic story of forbidden love and something of a rescue tale — all taking place off the coast of Japan, circa 1799. Postmodern it’s not.”

There’s a certain reticence in Eggers’s review to situate Thousand Autumns against anything but itself, including even the rest of Mitchell’s works. In contrast, Wood spends the first half of his review positioning Mitchell’s postmodernism, throughout both his novels (against each other), and as the oeuvre of one author (against other authors). For Wood, Thousand Autumns, because of “its self-enclosed quality [. . .] represents an assertion of pure fictionality.” He continues, arguing that “although the book contains no literary games, it is itself a kind of long game.” Wood would like to see in Thousand Autumns‘s discrete self-containedness a kind of literary gesture, perhaps a sort of conventional historical novel (in scare quotes) that is so conventional as to efface all signs of self-awareness (and thus erase the scare quotes around the gesture). At the same time, Wood recognizes the power of storytelling in the book, asserting that this feature is what makes it a “representative late-postmodern document.” Wood continues:

In place of the grave silence that was the great theme of early postmodernism (or late modernism, if you prefer), language announcing a postwar exhaustion, its own impossibility, as in the work of Beckett or Blanchot, there is a confident profusion of narratives, an often comic abundance of story-making. Never, when reading Mitchell, does the reader worry that language may not be adequate to the task, and this seems to me both a fabulous fortune and a metaphysical deficiency.

These last sentiments are where I strongly disagree with Wood (as perhaps my lede attests)–the greatest strength of Mitchell’s work here is the fabulous fortune of its abundant storytelling. Far from being a metaphysical deficiency, the characters in Thousand Autumns, major and minor, repeatedly transcend their social, spiritual, economic, psychological, and physical confinement via storytelling. Again and again language breaks characters away from their isolation or imprisonment, gives them access to adventure and romance–to spirit. Ultimately, Wood condemns the book for this “metaphysical deficiency,” arguing that “the reader wants a kind of moral or metaphysical pressure that is absent, and that has ceded all the ground to pure storytelling.” (In Wood’s critical body, it is always “the reader,” never “this reader”). I think that the pleasure and power of pure storytelling is its own end, and perhaps it is this recognition that leads Eggers to pronounce of the book simply that “Postmodern it’s not.” And while this declaration is ultimately a more reader-friendly take on Thousand Autumns, it’s also clear to see how the experimental nature of Mitchell’s previous work calls for Wood’s need to place the novel, to situate it against a developing canon (even if Wood chooses ultimately to deny its status).

Wood is perhaps right in his assertion that the term “post-postmodernism” leads to an “infinite stutter.” Still, post-postmodernism ultimately seems more fitting to describe Thousand Autumns than Wood’s “late postmodernism.” The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet cunningly sets the spiky traps of language and then gracefully leaps over them. Like David Foster Wallace and William Vollmann–two writers who I believe mark the beginnings of post-postmodernism–Mitchell wants to transcend postmodernism’s ironic vision, and storytelling–giving his characters voices–is a means to this end. Perhaps it is Mitchell’s earnestness in conveying the power of storytelling leads Wood to conclude Thousand Autumns “a kind of fantasy [. . .] Or, rather, it is a brilliant fairy tale; and even nightingales, as a Russian proverb has it, can’t live off fairy tales.” If, finally, Thousand Autumns is not a late postmodernist historical fiction but indeed a fairy tale, then it’s worth noting that it’s a particularly enjoyable and nourishing one. Highly recommended.