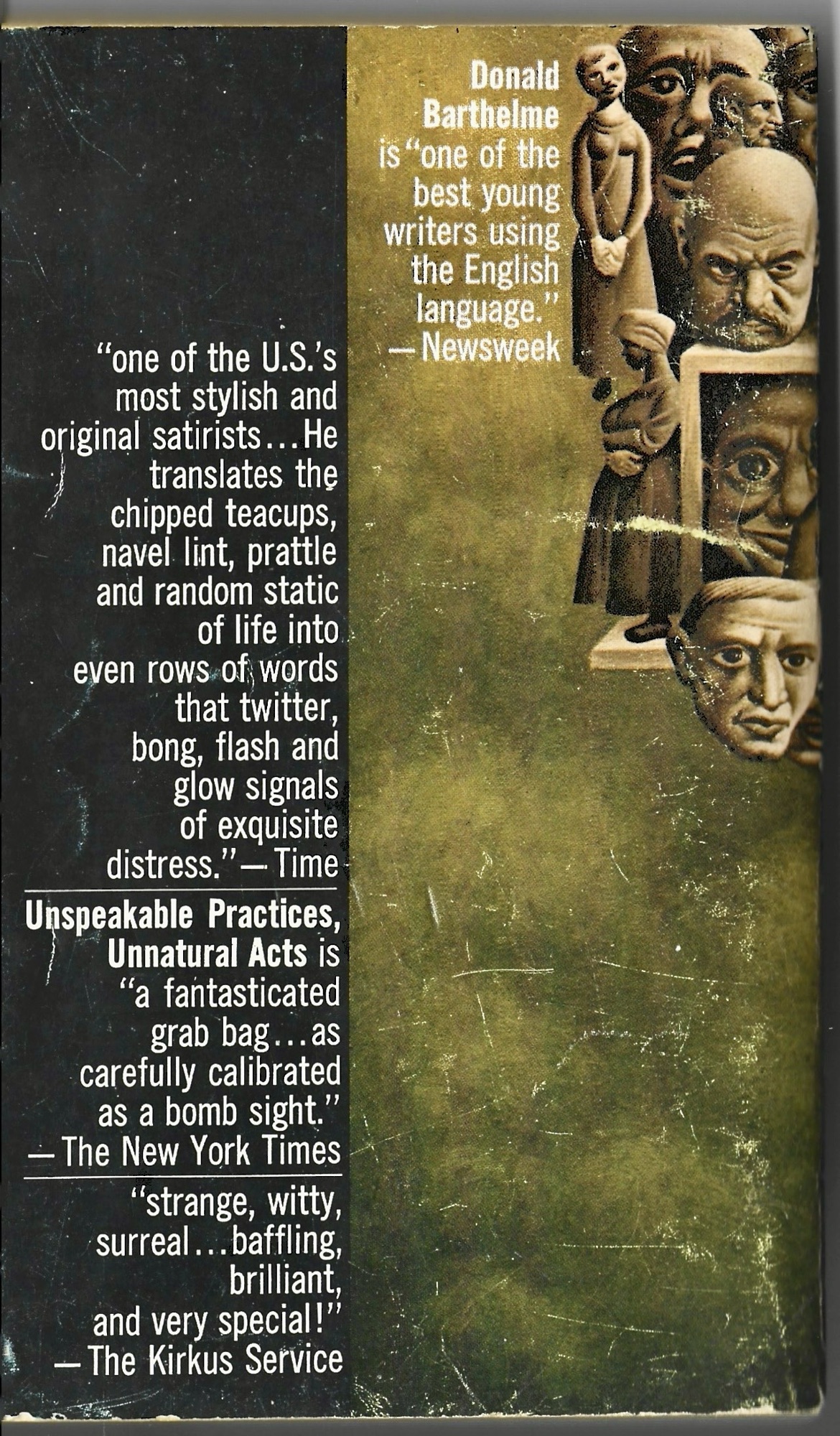

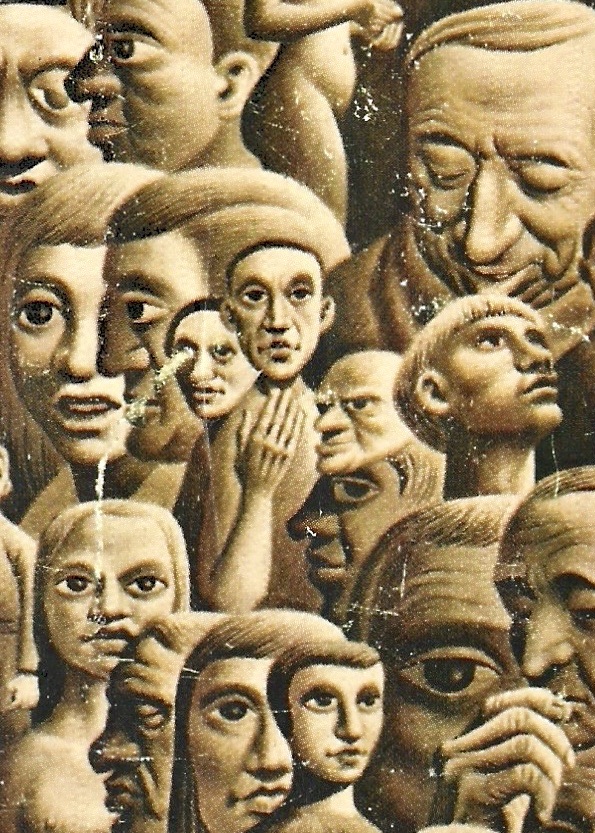

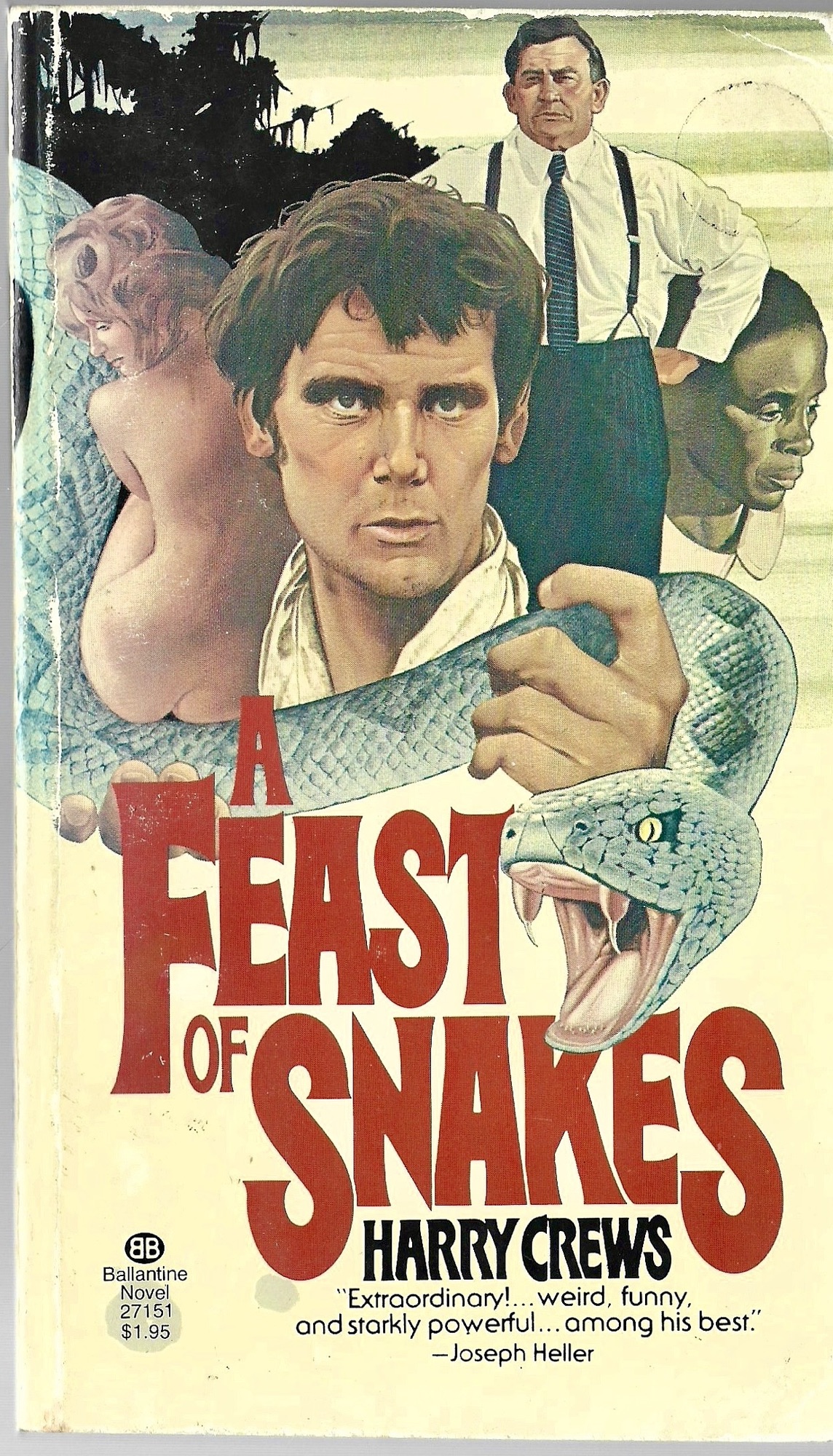

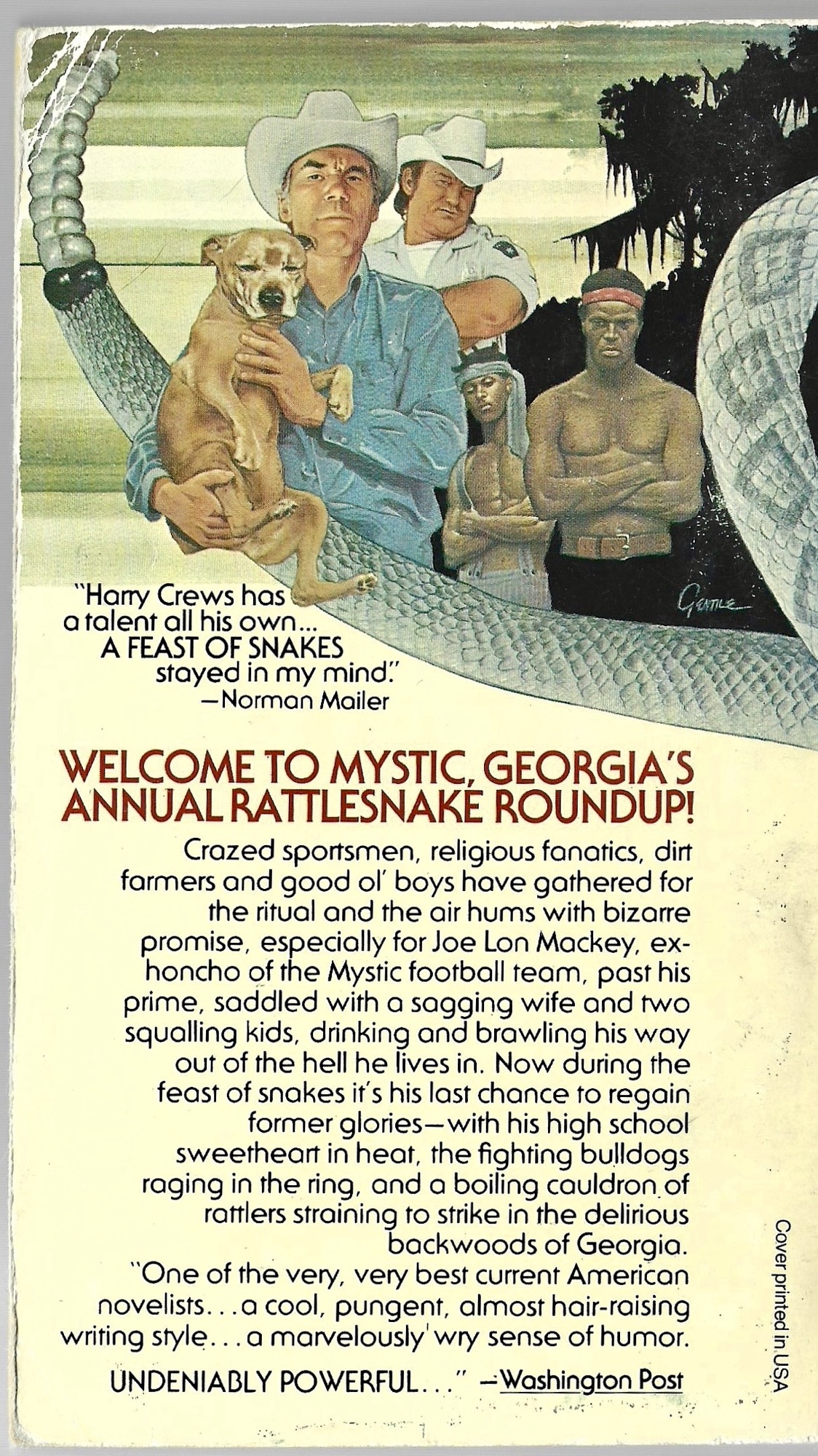

A Feast of Snakes, Harry Crews. Ballantine Books, first edition, first printing (1978). No cover artist credited. 165 pages.

While the cover designer and artist aren’t credited, there is a signature on the back which I believe is “Gentile.” If anyone has a guess as to the artist’s full name I’d be happy to hear it.

From the novel: not quite a recipe for snakes:

When they got to his purple double-wide, Joe Lon skinned snakes in a frenzy. He picked up the snakes by the tails as he dipped them out of the metal drums and swung them around and around his head and then popped them like a cowwhip, which caused their heads to explode. Then he nailed them up on a board in the pen and skinned them out with a pair of wire pliers. Elfie was standing in the door of the trailer behind them with a baby on her hip. Full of beer and fascinated with what Joe Lon could feel—or thought he could—the weight of her gaze on his back while he popped and skinned the snakes. He finally turned and looked at her, pulling his lips back from his teeth in a smile that only shamed him.

He called across the yard to her. “Thought we’d cook up some snake and stuff, darlin, have ourselves a feast.”

Her face brightened in the door and she said: “Course we can, Joe Lon, honey.”

Elfie brought him a pan and Joe Lon cut the snakes into half-inch steaks. Duffy turned to Elfie and said: “My name is Duffy Deeter and this is something fine. Want to tell me how you cook up snakes?”

Elfie smiled, trying not to show her teeth. “It’s lots of ways. Way I do mostly is I soak’m in vinegar about ten minutes, drain’m off good, and sprinkle me a little Looseanner redhot on’m, roll’m in flour, and fry’m is the way I mostly do.”