Art is the most sublime and the most revolting thing simultaneously, he said. But we must make ourselves believe that there is high art and the highest art, he said, otherwise we should despair. Even though we know that all art ends in gaucherie and in ludicrousness and in the refuse of history, like everything else, we must, with downright self-assurance, believe in high and in the highest art, he said. We realize what it is, a bungled, failed art, but we need not always hold this realization before us, because in that case we should inevitably perish, he said.

Tag: Thomas Bernhard

Thomas Bernhard’s Atzbacher on State-Sanctioned Corpses

Irrsigler has that irritating stare which museum attendants employ in order to intimidate the visitors who, as is well known, are endowed with all kinds of bad behaviour; his manner of abruptly and utterly soundlessly appearing round the corner of whatever room in order to inspect it is indeed repulsive to anyone who does not know him; in his grey uniform, badly cut and yet intended for eternity, held together by large black buttons and hanging on his meagre body as if from a coat rack, and with his peaked cap tailored from the same grey cloth, he is more reminiscent of a warder in one of our penal institutions than of a state-employed guardian of works of art. Ever since I have known him Irrsigler has always been as pale as he now is, even though he is not sick, and Reger has for decades described him as a state corpse on duty at the Kunsthistorisches Museum for over thirty-six years.

–Thomas Bernhard, Old Masters, trans. Ewald Osers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

“Many ideas turn into lifelong disfigurements” (Thomas Bernhard)

“Many ideas turn into lifelong disfigurements,” he said. The ideas often surprised one years later, but sooner or later they would always make the one who had had them look ridiculous. The ideas came from a place they never left. They would always remain there, in that place: it was the place of dreams. “The idea doesn’t exist that can be expunged or expunge itself. The idea is actual, and remains so.” Last night, he had been thinking about pain. “Pain doesn’t exist. A necessary illusion,” he said. Pain wasn’t pain, not in the way a cow was a cow. “The word ‘pain’ directs the attention of a feeling toward a feeling. Pain is overplus. But the illusion of it is real.” Accordingly, pain both was and was not. “But there is no pain,” he said. “Just as there is no happiness. Found an architecture on pain.” All thoughts and images were as involuntary as the concepts: chemistry, physics, geometry. “You have to understand these concepts to know something. To know everything.” Philosophy didn’t take you a single step nearer. “Nothing is progressive, but nothing is less progressive than philosophy. Progress is tripe. Impossible.” The observations of mathematics were foundational. “Oh, yes,” he said, “in mathematics everything’s child’s play.” And just like so-called child’s play, mathematics could finish you. “If you’ve crossed the border, and you suddenly no longer get the joke, and see what the world’s about, don’t see what anything’s about anymore. Everything’s just the imagining of pain. A dog has as much gravity as a human being, but he hasn’t lived, do you understand!” One day I would cross a threshold into an enormous park, an endless and beautiful park; in this park one ingenious invention would succeed another. Plants and music would follow in lovely mathematical alternation, delightful to the ear and answering to the utmost notions of delicacy; but this park was not there to be used, or wandered about in, because it consisted of a thousand and one small and minuscule square and rectilinear and circular islets, pieces of lawn, each of them so individual that I would be unable to leave the one on which I was standing. “In each case, there is a breadth and depth of water that prevents one from hopping from one island to another. In my imagining. On the piece of grass which one has reached, how is a mystery, on which one has woken up, and where one is compelled to stay,” one would finally perish of hunger and thirst. “One’s longing to be able to walk through the whole park is finally deadly.”

—From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Frost.

“Childhood is still running along beside us like a little dog” (Thomas Bernhard)

“Childhood is still running along beside us like a little dog who used to be a merry companion, but who now requires our care and splints, and myriad medicines, to prevent him from promptly passing on.” It went along rivers, and down mountain gorges. If you gave it any assistance, the evening would construct the most elaborate and costly lies. But it wouldn’t save you from pain and indignity. Lurking cats crossed your path with sinister thoughts. Like him, so nettles would sometimes draw me into fiendish moments of unchastity. As with him, my fear was made palatable by raspberries and blackberries. A swarm of crows were an instant manifestation of death. Rain produced damp and despair. Joy pearled off the crowns of sorrel plants. “The blanket of snow covers the earth like a sick child.” No infatuation, no ridicule, no sacrifice. “In classrooms, simple ideas assembled themselves, and on and on.” Then stores in town, butchers’ shop smells. Façades and walls, nothing but façades and walls, until you got out into the country again, quite abruptly, from one day to the next. Where the meadows began, yellow and green; brown plowland, black trees. Childhood: shaken down from a tree, so much fruit and no time! The secret of his childhood was contained in himself. Growing up wild, among horses, poultry, milk, and honey. And then: being evicted from this primal condition, bound to intentions that went way beyond himself. Designs. His possibilities multiplied, then dwindled in the course of a tearful afternoon. Down to three or four certainties. Immutable certainties. “How soon it is possible to spot dislike. Even without words, a child wants everything. And attains nothing.” Children are much more inscrutable than adults. “Protractors of history. Conscienceless. Correctors of history. Bringers-on of defeat. Ruthless as you please.” As soon as it could blow its own nose, a child was deadly to anything it came in touch with. Often—as it does me—it gives him a shock, when he feels a sensation he had as a child, provoked by a smell or a color, but that doesn’t remember him. “At such a moment you feel horribly alone.”

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Frost.

“—you see you were always lost” (Thomas Bernhard)

“You just arrive in a place,” said the painter,“ and then you leave it again, and yet everything, every single object you take in, is the sum of its prehistory. The older you become, the less you think about the connections you’ve already established. Table, cow, sky, stream, stone, tree, they’ve all been studied. Now they just get handled. Objects, the harmonic range of invention, completely unappreciated, no more truck with variation, deepening, gradation. You just try to work out the big connections. Suddenly you look into the macro-structure of the world, and you discover it: a vast ornament of space, nothing else. Humble backgrounds, vast replications—you see you were always lost. As you get older, thinking becomes a tormenting reference mechanism. No merit to it. I say ‘tree,’ and I see huge forests. I say ‘river,’ and I see every river. I say ‘house,’ and I see cities with their seas of roofs. I say ‘snow,’ and I see oceans of it. A thought sets off the whole thing. Where it takes art is to think small as well as big, to be present on every scale …”

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Frost.

“Bernhard is an architect of consciousness” — Ben Marcus on Thomas Bernhard

Bernhard is an architect of consciousness more than a narrative storyteller. His project is not to reference the known world, stuffing it with fully rounded characters who commence to discover their conflicts with one another, but to erect complex states of mind-usually self-loathing, obsessive ones-and then set about destroying them. Bernhard’s characters are thorough accomplices in their own destruction, and they are bestowed with a language that is dementedly repetitive and besotted with the appurtenances of logical thinking. The devious rationality of Bernhard’s language strives for a severe authority, and it tends to make his characters seem believable, no matter how unhinged their claims. Phrases don’t get repeated so much as needled until they yield graver meanings, with incremental changes introduced as though a deranged scientist were adding and removing substances in the performance of an experiment. “You wake up, and you feel molested,” Strauch says:

In fact: the hideous thing. You open your chest of drawers :a further molestation. Washing and dressing are molestations. Having to get dressed! Having to eat breakfast! When you go out on the street you are subject to the gravest possible molestations. You are unable to shield yourself. You lay about yourself, but it’s no use. The blows you dole out are returned a hundred fold. What are streets, anyway? Wendings of molestation, up and down. Squares? Bundled together molestations.

Without a story to drive it, Frost builds not through unfolding events but by telemarking around Strauch’s bitter cosmology while the narrator follows him through the woods, fattening himself on the rage of his new mentor. A chart of Strauch’s worldview would produce a splotchy Rorschach of points and counterpoints, contradictions, reversals, and the occasional backflip, none of which could really hold up to a logician’s scrutiny, which adds to his mystery. Strauch, a failed artist who only painted in total darkness, is opposed to nearly everything, and lest you think he’s a humanist at the core, with a fondness for the arts (that classic virtue of the misanthrope), he claims that “artists are the sons and daughters of loathsomeness, of paradisiac shamelessness, the original sons and daughters of lewdness; artists, painters, writers and musicians are the compulsive masturbators on the planet.”

From Ben Marcus’s 2011 essay “Misery Loves Nothing,” first published in Harper’s and available in full for free at Marcus’s site. I’m about halfway through Bernhard’s early novel Frost, a book that is very dark, bitter, intriguing, and funny. Very very funny.

Gargoyles, Thomas Bernhard’s Philosophical Novel of Abject Madness

In its English translation, Thomas Bernhard’s 1967 breakthrough novel Verstörung received the title Gargoyles. Verstörung translates to something like distress or disturbance, while Gargoyles (obviously) evokes Gothic monsters. Considered together, both titles communicate this philosophical novel’s themes of abjection, decay, and madness.

Bernhard explores these themes by dividing the novel into two sections that occur over the span of the same day. In the first section, “First Page,” a country doctor takes his son on his daily rounds in rural Stryia, “a relatively large and ‘difficult’ district.” The son, a mining engineer student and aspiring scientist, is ostensibly the narrator of Gargoyles. He tells us that his father “was taking me with him for the sake of my studies.” Their journey culminates in a visit to Hochgobernitz, the gloomy castle of Prince Saurau, an insane, suicidal aristocrat who mourns his own son’s self-exile to England, where he has gone to study. While the doctor’s son remains the narrator of the book in “The Prince,” the second part of Gargoyles, Prince Saurau overwhelms the novel with the force of his monologue, a tirade that gobbles up all that comes before it. His monologue ventriloquizes the narrator’s consciousness, echoing in the young man’s skull long after he’s left the castle.

The prince’s monologue is a prototypical Bernhardian rant that will be familiar to anyone who’s read The Loser or Correction (and undoubtedly other Bernhard novels I haven’t read yet). Unlike those novels, Gargoyles offers its first section “First Page” as a point of contrast to the monologue that will come later. These episodes are short and digestible, and while hardly conventional, they are far easier to handle than the sustained intensity of the prince’s monologue. The grotesque cavalcade that the doctor and son trek through in “First Page” allows Bernhard to set out his themes — not neatly or precisely, but clearly — before the prince commences to swallow and then vomit them.

Here are the first two paragraphs of the novel:

On the twenty-sixth my father drove off to Salla at two o’clock in the morning to see to a schoolteacher whom he found dying and left dead. From there he set out toward Hüllberg to treat a child who had fallen into a hog tub full of boiling water that spring. Discharged from the hospital weeks ago, it was now back with its parents.

He liked seeing the child, and dropped by there whenever he could. The parents were simple people, the father a miner in Köflach, the mother a servant in a butcher’s household in Voitsberg. But the child was not left alone all day; it was in the care of one of the mother’s sisters. On this day my father described the child to me in greater detail than ever before, adding that he was afraid it had only a short time to live. “I can say for a certainty that it won’t last through the winter, so I am going to see it as often as possible now,” he said. It struck me that he spoke of the child as a beloved person, very quietly and without having to consider his words.

The specter of infanticide and the doctor’s resistance to it haunts the novel. We can also sense a cerebral chilliness in the narrator, who is “struck” by his father’s empathy. The doctor’s empathy repeats throughout the novel; we next see it clearly when he’s brought to attend an innkeeper’s wife assaulted in the early morning “without the slightest provocation” by one of the drunken miners who frequented her inn. Unconscious for hours before police or doctor are even called for, the woman dies. But—

It was of no importance that the innkeeper had not notified him of the fatal blow until three hours after the incident, my father said. The woman could not have been saved. The deceased woman was thirty-three, and my father had known her for years. It had always seemed to him that innkeepers treated their wives with extreme callousness, he said. They themselves usually went to bed early, having overworked themselves all day on their slaughtering, their cattle dealing, their farms. But because they thought of nothing but the business, they left their wives to take care of the taverns until the early morning hours, exposed to the male clients who drank steadily so that as the night wore on their natural brutality became less and less restrained.

As the day unfolds, the “natural brutality” that the doctor is up against evinces again and again in the various gargoyles he attends to. The rumor of the innkeeper’s wife’s murder floats in the background as a reminder of violence and brutality that bizarrely unites this community of outsiders.

Those outsiders: a bedridden, dying woman with a feeble-minded son and a murderer for a brother; a retired industrialist, living “like man and wife” with his half-sister, who devotes “himself to a literary work over which he agonized, even as it kept his mind off his inner agony”; the school teacher whose death initiates the novel; mill workers murdering exotic birds with the help of a young bewildered Turk; an insane and deformed man, the son’s age, attended to and cared for by his sister. And the prince. But I’ve rushed through so much here, so much force of language, so much terror, so much horror.

These gargoyles live, if it can be called that, in abject, isolated otherness. The doctor diagnoses it for his son:

. . . no human being could continue to exist in such total isolation without doing severe damage to his intellect and psyche. It was a well-known phenomenon, my father said, that at a crisis in their lives some people seek out a dungeon, voluntarily enter it, and devote their lives—which they regard as philosophically oriented—to some scholarly task or to some imaginative scientific obsession. They always take with them into their dungeon some creature who is attached to them. In most cases they sooner or later destroy this creature who has entered the dungeon with them, and then themselves. The process always goes slowly at first.

There is something of a warning here for the doctor’s son, who tells us at one point: “Every day I completely built myself up, and completely destroyed myself.” Like Roithamer of Correction, the son is something of a control freak (“Only through such control can man be happy and perceive his own nature”), and, like Roithamer and so many other Bernhardian figures, he has a frail (perhaps suicidal) sister who could perhaps fall prey to his idealism—who might indeed be the “creature who has entered the dungeon” with him.

There’s also the risk, one which the doctor perhaps did not account for when he set out to help his son with his “studies,” that the son might fall into the prince’s dungeon. But perhaps I’m making too much of the doctor’s empathy, of his resistance to brutality and his commitment to caring for those who repel all others. His own philosophy seems coded in misanthropy and failure. “All of living is nothing but a fervid attempt to move closer together,” he says at one point. But also: “Communication is impossible.”

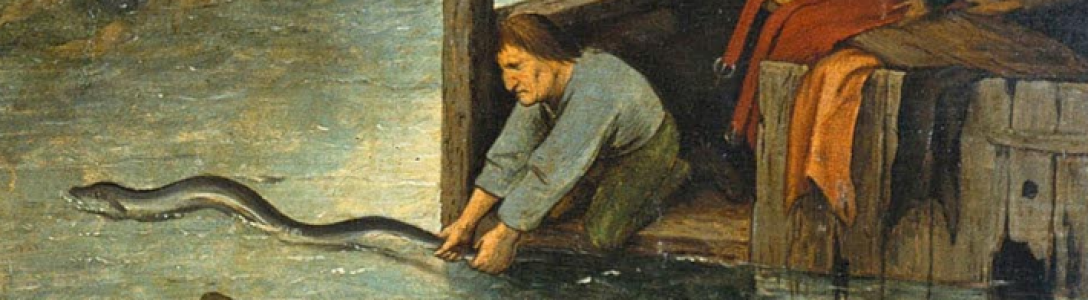

The resistance to abjection is paradoxical—as the doctor points out, the “philosophically oriented” and “imaginative scientific obsession[s]” often lead people deeper into the abyss—as the prince’s monologue will illustrate. Each of the gargoyles presented in the text offers a rare and special talent—art, music, philosophy, etc. Sussing out the novel’s treatment of the philosophies it invokes is beyond my ken, but I can’t resist lazily dropping a few names: Kant, Marx, Nietzsche, Pascal, Diederot (all on the doctor’s reading list), and Schopenhauer, whose philosophy of the will surely informs the text more than I can manage here. (From the prince’s father’s suicide note: “Schopenhauer has always been the best nourishment for me”). And while I’m lazily dropping names: Edgar Allan Poe, King Lear, Macbeth, Dostoevsky, and Francisco Goya—especially his Los caprichos, a few of which accompany this review . (And although he came after, I can’t help but read Roberto Bolaño in some of the more grotesque, horrific passages).

The levels of ventriloquizing and the layers of madness set against the novel’s depiction of radical repression lead to an abyssal paradox, perhaps best figured not in the philosophers Bernhard invokes but in the novel’s backdrop: a dark, enveloping gorge, the yawning chasm that surrounds the high walls of the castle the prince walks with his auditors. These walls are the stage from which the prince performs his monologue; their visceral dramatic emphasis derives from the abyss below. In an ironic note at the beginning of “The Prince,” the son remarks, “From here, I thought, you probably had the finest view of the entire country.”

Upon this stage, Bernhard’s main characters function as asymmetrical parallels (forgive the purposeful absurdity of this oxymoron). The father and his son the narrator are set against the prince and his absent son. In a particularly bizarre episode, the prince recounts a dream:

“But my son,” he said, “will destroy Hochgobernitz as soon as he receives it into his hands.”

Last night, the prince said, he had had a dream. “In this dream,” he said, “I was able to look at a sheet of paper moving slowly from far below to high up, paper on which my own son had written the following. I see every word that my son is writing on that sheet of paper,” the prince said. “It is my son’s hand writing it. My son writes: As one who has taken refuge in scientific allegories I seemed to have cured myself of my father for good, as one cures oneself of a contagious disease. But today I see that this disease is an elemental, shattering fatal illness of which everyone without exception dies. Eight months after my father’s suicide—note that, Doctor, after his father’s suicide, after my suicide; my son writes about my suicide!—eight months after my father’s suicide everything is already ruined, and I can say that I have ruined it. I can say that I have ruined Hochgobernitz, my son writes, and he writes: I have ruined this flourishing economy! This tremendous, anachronistic agricultural and forest economy. I suddenly see, my son writes,” the prince said, “that by liquidating the business even though or precisely because it is the best, I am for the first time implementing my theory, my son writes!” the prince said.

Note the strange layers of narration and creation here. The prince’s son, a creation of the prince, exists in the prince’s dream (another creation) where he creates a manuscript. All this creation though points to destruction—of the father, of the ancestral estate. The prince’s impulses signal self-erasure, suicide as a kind of radical return of the repressed (here, Austria’s inability to speak about, reconcile, admit its complicity in the horrors of World War 2).

The doctor contrasts with the prince, perhaps representing an order, health, and sanity that serve to sharpen and darken the abject decay of the crazed aristocrat. “My father goes to see the prince only to treat him for his insomnia,” observes the narrator, “without doing anything about his real illness . . . his madness.” But can the doctor really treat the prince’s illness?

Both fathers in their respective philosophies signal the possible paths that might be inherited by their sons (and, if you like, by allegorical extension the sons could represent Austria, or perhaps even Western Europe). How to live against the promise of suicide, against the perils of infanticide, against the kind of “natural brutality” that leads to murder, insanity, the abyss?

This problem is encoded into Bernhard’s rhetorical technique. The prince’s devastating monologue consumes the narrative, reader and narrator alike. By the end of the novel, he’s infiltrated (and perhaps infected) the narrator’s consciousness, highlighting the dramatic stakes here—of being ventriloquized, possessed by the diseases of history and authority—an illness that trends to self-destruction. It’s worth sharing a passage at some length; the following section highlights and perhaps even condenses what I take to be the core themes of Gargoyles:

“Whenever I look at people, I look at unhappy people,” the prince said. “They are people who carry their torment into the streets and thus make the world a comedy, which is of course laughable. In this comedy they all suffer from tumors both mental and physical; they take pleasure in their fatal illness. When they hear its name, no matter whether the scene is London, Brussels, or Styria, they are frightened, but they try not to show their fright. All these people conceal the actual play within the comedy that this world is. Whenever they feel themselves unobserved, they run away from themselves toward themselves. Grotesque. But we do not even see the most ridiculous side of it because the most ridiculous side is always the reverse side. God sometimes speaks to them, but he uses the same vulgar words as they themselves, the same clumsy phrases. Whether a person has a gigantic factory or a gigantic farm or an equally gigantic sentence of Pascal’s in his head, is all the same,” the prince said. “It is poverty that makes people the same; at the human core, even the greatest wealth is poverty. In men’s minds and bodies poverty is always simultaneously a poverty of the body and a poverty of the mind, which necessarily makes them sick and drives them mad. Listen to me, Doctor, all my life I have seen nothing but sick people and madmen. Wherever I look, the worn and the dying look back at me. All the billions of the human race spread over the five continents are nothing but one vast community of the dying. Comedy!” the prince said. “Every person I see and everyone I hear anything about, no matter what it is, prove to me the absolute obtuseness of this whole human race and that this whole human race and all of nature are a fraud. Comedy. The world actually is, as has so often been said, a stage on which roles are forever being rehearsed. Wherever we look it is a perpetual learning to speak and learning to walk and learning to think and learning by heart, learning to cheat, learning to die, learning to be dead. This is what takes up all our time. Men are nothing but actors putting on a show all too familiar to us. Learners of roles,” the prince said. “Each of us is forever learning one (his) or several or all imaginable roles, without knowing why he is learning them (or for whom). This stage is an unending torment and no one feels that the events on it are a pleasure. But everything that happens on this stage happens naturally. A critic to explain the play is constantly being sought. When the curtain rises, everything is over.” Life, he went on, changing his image, was a school in which death was being taught. It was filled with millions and billions of pupils and teachers. The world was the school of death. “First the world is the elementary school of death, then the secondary school of death, then, for the very few, the university of death,” the prince said. People alternate as teachers or pupils in these schools. “The only attainable goal of study is death,” he said.

Such searing nihilism here—the prince angrily mourns the grotesqueness of the world, the lack of agency of people to control their own fate, to be but players, dummies mumbling someone else’s script. And it all leads to death. For the prince, dialogue is impossible in the face of this death: “All interlocutors are always mutually pushing one another into all abysses.” But the prince, notably, is his own interlocutor; he pushes himself into abysses of his own contrivance.

Neither is love a solution for the prince:

“We face questions like an open grave about to be filled. It is also absurd, you know, for me to be talking of the absurdity,” he said. “My character can justly be called thoroughly unloving. But with equal justice I call the world utterly unloving. Love is an absurdity for which there is no place in nature.

And community?

We see in a person frailties which at once make us see the frailties of the community in which we live, the frailties of all communities, the state; we feel them, we see through them, we catastrophize them.

But is this necessarily the essential view of the novel? I don’t think it plausible to argue that the prince’s monologue be read entirely ironically, but it’s worth bearing in mind that both his auditors understand him to be mentally ill and terribly isolated. The guy is histrionic, a drama fiend holding forth on his stage. And while his acerbic misanthropy and nihilism may scorch, it’s also very, very funny. I chuckled a lot reading Gargoyles.

But yes—the prince is sincere in his pain. “We assume the spirit of the walls that surround us,” he declares near the end of the novel. He’s a a prisoner in his own gloomy castle, the dungeon he refuses to leave. He resents his son’s self-exile to London, but also longs—literally dreams for—his son to return to destroy that dungeon.

Of his family: “But probably all these creatures deserve ruthlessness more than pity.” I think that But is important here. The doctor, like the prince, also situates everyone on an axis of ruthlessness and pity. The doctor is full of cruel observations about the gargoyles he encounters. But: But he gets up, goes out, does his rounds, tries in some way to mitigate some of the “natural brutality” of the world. And he tries to show this world—and this method—to his son this as well, for his son’s “studies.” In the room of the lonely, dying woman, the son remarks of his father: “I noticed that he made an effort to stretch out the call, for all his eagerness to leave.” The son, in thrall to the prince’s monologue, perhaps fails to notice that his father also stretches out his time on the castle wall despite an eagerness to leave the prince.

By the end of the novel, we see the prince’s consciousness inhabiting the son’s thoughts:

In bed I thought: What did the prince say? “Always wanting to change everything has been a constant craving with me, an outrageous desire which leads to the most painful disputes. The catastrophe begins with getting out of bed.

The pessimism and sheer despair here erupts into black comedy with that last line, one echoed in Bernhard’s later novel Correction: “Waking up is the always frightening minimum of existence.” If to simply get out of bed (which, of course, is where the son is as he work’s through the prince’s ideas) is to invoke and invite disaster and despair, it’s worth noting that this simple action—getting out of bed—is what the doctor performs each day, even if it means he wakes to a dead teacher, a boiled infant, a murdered wife. While hardly a beacon of optimism or hope, the doctor nonetheless figures an alternative to the prince’s abject madness. If we “assume the spirit of the walls that surround us,” the doctor understands that it’s important to leave those walls, to not seek out dungeons—and drag others into dungeons with us.

Gargoyles is by turns bleak and nihilistic. It’s also energetic, profound, and at times very, very funny. Its opening section will likely provide an accessible introduction to readers interested in Bernhard, with the prince’s monologue offering the full Bernhardian experience. Dark, cruel, and taxing, Gargoyles isn’t particularly fun reading—except when it is. Highly recommended.

“Whenever I look at people, I look at unhappy people” (Thomas Bernhard’s Gargoyles)

“Whenever I look at people, I look at unhappy people,” the prince said. “They are people who carry their torment into the streets and thus make the world a comedy, which is of course laughable. In this comedy they all suffer from tumors both mental and physical; they take pleasure in their fatal illness. When they hear its name, no matter whether the scene is London, Brussels, or Styria, they are frightened, but they try not to show their fright. All these people conceal the actual play within the comedy that this world is. Whenever they feel themselves unobserved, they run away from themselves toward themselves. Grotesque. But we do not even see the most ridiculous side of it because the most ridiculous side is always the reverse side. God sometimes speaks to them, but he uses the same vulgar words as they themselves, the same clumsy phrases. Whether a person has a gigantic factory or a gigantic farm or an equally gigantic sentence of Pascal’s in his head, is all the same,” the prince said. “It is poverty that makes people the same; at the human core, even the greatest wealth is poverty. In men’s minds and bodies poverty is always simultaneously a poverty of the body and a poverty of the mind, which necessarily makes them sick and drives them mad. Listen to me, Doctor, all my life I have seen nothing but sick people and madmen. Wherever I look, the worn and the dying look back at me. All the billions of the human race spread over the five continents are nothing but one vast community of the dying. Comedy!” the prince said. “Every person I see and everyone I hear anything about, no matter what it is, prove to me the absolute obtuseness of this whole human race and that this whole human race and all of nature are a fraud. Comedy. The world actually is, as has so often been said, a stage on which roles are forever being rehearsed. Wherever we look it is a perpetual learning to speak and learning to walk and learning to think and learning by heart, learning to cheat, learning to die, learning to be dead. This is what takes up all our time. Men are nothing but actors putting on a show all too familiar to us. Learners of roles,” the prince said. “Each of us is forever learning one (his) or several or all imaginable roles, without knowing why he is learning them (or for whom). This stage is an unending torment and no one feels that the events on it are a pleasure. But everything that happens on this stage happens naturally. A critic to explain the play is constantly being sought. When the curtain rises, everything is over.” Life, he went on, changing his image, was a school in which death was being taught. It was filled with millions and billions of pupils and teachers. The world was the school of death. “First the world is the elementary school of death, then the secondary school of death, then, for the very few, the university of death,” the prince said. People alternate as teachers or pupils in these schools. “The only attainable goal of study is death,” he said.

—From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Gargoyles.

From Thomas Bernhard’s Novel Gargoyles, The Story of the Deceased Teacher

While we ate, my father also told me the following story about the deceased teacher. Once when he was a boy, his grandmother had taken him along into the deep woods to pick blackberries. They lost their way completely, wandered for hours, and could not find the way out of the woods. Darkness fell, and still they had not found the path. They kept going in the wrong direction all the time. Finally grandmother and grandson curled up in a hollow, and lying pressed close together, survived the night. They were lost all the next day and spent a second night in another refuge. Not until the afternoon of the second day did they suddenly emerge from the woods, only to find they had all along gone in a direction opposite from that of their home. Totally exhausted, they had struggled on to the nearest farmhouse.

This ordeal had quickly brought about the grandmother’s death. And her grandson, not yet six, had had his entire future ruined by it, my father said.

You could always conclude that the disasters in a man’s life derived from earlier, usually very early, injuries to his body and his psyche, my father averred. Modern medicine was aware of this, but still made far too little use of such knowledge.

“Even today most doctors do not look into causes,” my father said. “They concern themselves only with the most elementary patterns of treatment. They’re hypocrites who do nothing but prescribe medicines and close their eyes to the psyches of people who because of their helplessness and a disastrous tradition entrust themselves completely to their doctors. And most doctors are lazy and cowardly.”

Putting yourself at their mercy meant putting yourself at the mercy of chance and total unfeelingness, trusting to a pseudo-science, my father said. “Most doctors nowadays are unskilled workers in medicine. And the greatest mystifiers. I never feel more insecure than when I’m among my colleagues. Nothing is more sinister than medicine.”

In the last months of his life the teacher had developed an astonishing gift for pen drawing, my father said. The demonic elements that more and more came to light in his drawings shocked his parents. In delicate lines he drew a world “intent upon self-destruction” that terrified them: birds torn to pieces, human tongues ripped out by the roots, eight-fingered hands, smashed heads, extremities torn from bodies not shown, feet, hands, genitals, people suffocated as they walked, and so on. In those last months the bony structure of the young man’s skull became more and more prominent. And he drew his own portrait frequently, hundreds, thousands of times. When the young teacher talked, the disastrous way his mind was set became apparent. My father had considered taking some of the drawings and showing them to a gallery owner he knew in Graz. “They would make a good exhibition,” he said. “I don’t know anyone who draws the way the teacher did.” The teacher’s surrealism was something completely original, for there was nothing surreal in his drawings; what they showed was reality itself. “The world is surrealistic through and through,” my father said. “Nature is surrealistic, everything is surrealistic.” But he felt that art one exhibited was destroyed by the very act of being exhibited, and so he dropped the idea of doing anything with the teacher’s drawings. On the other hand, he was afraid the schoolmaster’s parents would throw away the drawings or burn them—thousands of them!—from ignorance of how good they were and because they were still frightened, anxious, and wrought up about these drawings. So he had decided to take them. “I’ll simply take them all with me,” he said. He had no doubt they would be handed over to him.

The teacher’s parents must have kept thinking of their sick son’s unfortunate bent whenever they looked at him during his last illness, my father said. “What a terrible thing it is that when you know of some deviation, some unnaturalness, or some crime in connection with a person, as long as he lives you can never look at him without thinking about that deviation, unnaturalness, or crime.”

From his bed the teacher had a view of the peak of the Bundscheck on one side and the rounded top of the Wölkerkogel on the other side. “You can feel this whole stark landscape in his drawings,” my father said.

The teacher’s parents said, however, that during his last days he had not spoken at all, only looked at the landscape outside his window. But the landscape he saw was entirely different from theirs, my father said, and different from the landscape we see when we look at it. What he depicted was an entirely different landscape, “everything totally different.”

—From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Gargoyles.

“Translations are always disgusting / But they brought me a lot of money” (Thomas Bernhard)

From Thomas Bernhard’s play Der Weltverbesserer (The World-Fixer). The translation here is by Gitta Honegger and appears as an illustrating example in her fantastic essay “Language Speaks. Anglo-Bernhard: Thomas Bernhard in Translation,” collected in A Companion to the Works of Thomas Bernhard (ed. Matthias Konzett). At the time of Companion’s first publication, Der Weltverbesserer had yet to be released in an English edition; Ariadne released one in 2005.

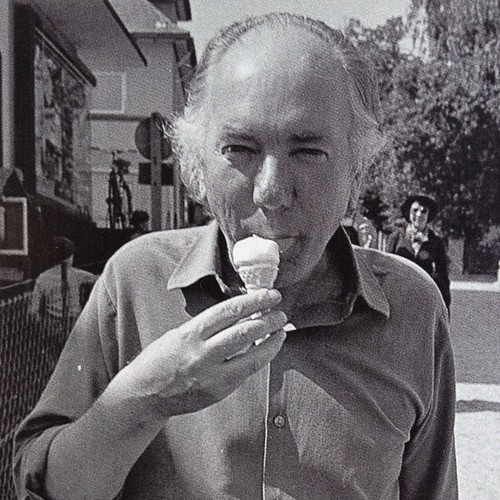

Thomas Bernhard Enjoying a Tiny Ice Cream Cone

(Via).

The Never-Ending Torture of Unrest | Georg Büchner’s Lenz Reviewed

Composed in 1836, Georg Büchner’s novella-fragment Lenz still seems ahead of its time. While Lenz’s themes of madness, art, and ennui can be found throughout literature, Büchner’s strange, wonderful prose and documentary aims bypass the constraints of his era.

Let me share some of that prose. Here is the opening paragraph of Lenz:

The 20th, Lenz walked through the mountains. Snow on the peaks and upper slopes, gray rock down into the valleys, swatches of green, boulders, firs. It was sopping cold, the water trickled down the rocks and leapt across the path. The fir boughs sagged in the damp air. Gray clouds drifted across the sky, but everything so stifling, and then the fog floated up and crept heavy and damp through the bushes, so sluggish, so clumsy. He walked onward, caring little one way or another, to him the path mattered not, now up , now down. He felt no fatigue, except sometimes it annoyed him that he could not walk on his head. At first he felt a tightening in his chest when the rocks skittered away, the gray woods below him shook, and the fog now engulfed the shapes, now half-revealed their powerful limbs; things were building up inside him, he was searching for something, as if for lost dreams, but was finding nothing. Everything seemed so small, so near, so wet, he would have liked to set the earth down behind an oven, he could not grasp why it took so much time to clamber down a slope, to reach a distant point; he was convinced he could cover it all with a pair of strides.

Büchner sets us on Lenz’s shoulder, moving us through the estranging countryside without any exposition that might lend us bearings. The environment impinges protagonist and reader alike, heavy, damp, stifling. Büchner’s syntax shuffles along, comma splices tripping us into Lenz’s manic consciousness, his mind-swings doubled in the path that is “now up, now down.” We feel the “tightening” in Lenz’s chest as the “rocks skittered away,” as the “woods below him shook” — the natural world seems to envelop him, cloak him, suffocate him. It’s an animist terrain, and Büchner divines those spirits again in the text. The claustrophobia Lenz experiences then swings to another extreme, as our hero, his consciousness inflated, feels “he could cover [the earth] with a pair of strides.

And that baffling line: “He felt no fatigue, except sometimes it annoyed him that he could not walk on his head.” Well.

The end notes to the Archipelago edition I read (translated by Richard Sieburth) offer Arnold Zweig’s suggestion that “this sentence marks the beginning of modern European prose,” as well as Paul Celan’s observation that “whoever walks on his head has heaven beneath him as an abyss.”

Celan’s description is apt, and Büchner’s story repeatedly invokes the abyss to evoke its hero’s precarious psyche. Poor Lenz, somnambulist bather, screamer, dreamer, often feels “within himself something . . . stirring and swarming toward an abyss toward which he was being swept by an inexorable force.” Lenz is the story of a young artist falling into despair and madness.

But perhaps I should offer a more lucid summary. I’ll do that in the next paragraph, but first: Let me just recommend you skip that paragraph. Really. What I perhaps loved most about Lenz was piecing together the plot through the often elliptical or opaque experiences we get via Büchner’s haunting free indirect style. The evocation of a consciousness in turmoil is probably best maintained when we read through the same confusion that Lenz experiences. I read the novella cold based on blurbs from William H. Gass and Harold Bloom and I’m glad I did.

Here is the summary paragraph you should skip: Jakob Lenz, a writer of the Sturm and Drung movement (and friend and rival to Goethe), has recently suffered a terrible episode of schizophrenia and “an accident” (likely a suicide attempt). He’s sent to pastor-physician J.F. Oberlin, who attends to him in the Alsatian countryside in the first few weeks of 1778. During this time Lenz obsesses over a young local girl who dies (he attempts to resurrect her), takes long walks in the countryside, cries manically, offers his own aesthetic theory, prays, takes loud late-night bath in the local fountain, receives a distressing letter, and, eventually, likely—although it’s never made entirely explicit—attempts suicide again and is thusly shipped away.

Büchner bases his story on sections of Oberlin’s diary, reproduced in the Archipelago edition. In straightforward prose, these entries fill in the expository gaps that Büchner has so elegantly removed and replaced with the wonder and dread of Lenz’s imagination. The diary’s lucid entries attest to the power of Büchner’s speculative fiction, to his own art and imagination, which so bracingly take us into a clouded mind.

In Sieburth’s afterword (which also offers a concise chronology of Lenz’s troubled life), our translator points out that “Like De Quincey’s “The Last Days of Immanuel Kant” or Chateaubriand’s Life of Rancé, Büchner’s Lenz is an experiment in speculative biography, part fact, part fabrication—an early nineteenth-century example of the modern genre of docufiction.” Obviously, any number of postmodern novels have explored or used historical figures—Public Burning, Ragtime, and Mason & Dixon are all easy go-to examples. But Lenz is more personal than these postmodern fictions, more an exploration of consciousness, and although we are treated to Lenz’s ideas about literature, art, and religion, we access this very much through his own skull and soul. He’s not just a placeholder or mouthpiece for Büchner.

Lenz strikes me as something closer to the docufiction of W.G. Sebald. Perhaps it’s all the ambulating; maybe it’s the melancholy; could be the philosophical tone. And, while I’m lazily, assbackwardly comparing Büchner’s book to writers who came much later: Thomas Bernhard. Maybe it’s the flights of rant that Lenz occasionally hits, or the madness, or the depictions of nature, or hell, maybe it’s those long, long passages. The comma splices.

Chronologically closer is the work of Edgar Allan Poe, whose depictions of manic bipolar depression resonate strongly with Lenz—not to mention the abysses, the torment, the spirits, the doppelgängers. Why not share another sample here to illustrate this claim? Okay:

The incidents during the night reached a horrific pitch. Only with the greatest effort did he fall asleep, having tried at length to fill the terrible void. Then he fell into a dreadful state between sleeping and waking; he bumped into something ghastly, hideous, madness took hold of him, he sat up, screaming violently, bathed in sweat, and only gradually found himself again. He had to begin with the simplest things in order to come back to himself. In fact he was not the one doing this but rather a powerful instinct for self preservation, it was as if he were double, the one half attempting to save the other, calling out to itself; he told stories, he recited poems out loud, wracked with anxiety, until he came to his sense.

Here, Lenz suspends his neurotic horror through storytelling and art—but it’s just that, only a suspension. Büchner doesn’t blithely, naïvely suggest that art has the power to permanently comfort those in despair; rather, Lenz repeatedly suggests that art, that storytelling is a symptom of despair.

What drives despair? Lenz—Lenz—Büchner (?)—suggests repeatedly that it’s Langeweile—boredom. Sieburth renders the German Langeweile as boredom, a choice I like, even though he might have been tempted to reach for its existentialist chain-smoking cousin ennui. When Lenz won’t get out of bed one day, Oberlin heads to his room to rouse him:

Oberlin had to repeat his questions at length before getting an answer: Yes, Reverend, you see, boredom! Boredom! O, sheer boredom, what more can I say, I have already drawn all the figures on the wall. Oberlin said to him he should turn to God; he laughed and said: if I were as lucky as you to have discovered such an agreeable pastime, yes, one could indeed wile away one’s time that way. Tedium the root of it all. Most people pray only out of boredom; others fall in love out of boredom, still others are virtuous or depraved, but I am nothing, nothing at all, I cannot even kill myself: too boring . . .

Lenz fits in neatly into the literature of boredom, a deep root that predates Dostoevsky, Camus, and Bellow, as well as contemporary novels like Lee Rourke’s The Canal and David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King.

Ultimately, the boredom Lenz circles around is deeply painful:

The half-hearted attempts at suicide he kept on making were not entirely serious, it was less the desire to die, death for him held no promise of peace or hope, than the attempt, at moments of excruciating anxiety or dull apathy bordering on non-existence bordering on non-existence, to snap back into himself through physical pain. But his happiest moments were when his mind seemed to gallop away on some madcap idea. This at least provided some relief and the wild look in his eye was less horrible than the anxious thirsting for deliverance, the never-ending torture of unrest!

The “never-ending torture of unrest” is the burden of existence we all carry, sloppily fumble, negotiate with an awkward grip and bent back. Büchner’s analysis fascinates in its refusal to lighten this burden or ponderously dwell on its existential weight. Instead, Lenz is a character study that the reader can’t quite get out of—we’re too inside the frame to see the full contours; precariously perched on Lenz’s shoulder, we have to jostle along with him, look through his wild eyes, gallop along with him on the energy of his madcap idea. The gallop is sad and beautiful and rewarding. Very highly recommended.

“Fear” — Thomas Bernhard

A Riff on Thomas Bernhard’s Novel The Loser

1. I finished Thomas Bernhard’s 1983 novel The Loser (English transl. Jack Dawson ’91) a few weeks ago and then picked over some of it again this week.

I’m not going to try to unpack all of The Loser here—it’s too thick, too loaded, too layered—its density is monochromatic, or monoglossic really, a monologue that threatens to drown the reader. One big paragraph.

2. The Loser is the second Bernhard novel I’ve read, after Correction, which is an even denser novel: Correction’s sentences are longer, its tone grimmer, its humor less readily apparent.

Correction is a novel about repetition. The Loser reads like a repetition of Correction: Like Correction, The Loser is one long uninterrupted monologue by an unnamed narrator who attempts to puzzle out the motives and meanings of a friend’s recent suicide. As in Correction, the suicide in The Loser (eponymous Wertheimer, whose name recalls Correction’s Roithamer) is a ridiculously wealthy man who obsesses almost incestuously over his sister, repressing her in the process. Like Correction, The Loser focuses on three friends. And like Correction, The Loser is ultimately about how idealism leads to breakdown, insanity, and suicide.

3. (I riffed on Correction here).

4. You might want a plot summary (always my least favorite business of a book review).

Here, straight from the text:

Wertheimer had wanted to compete with Glenn, I thought, to show his sister, to pay her back for everything by hanging himself only a hundred steps from her house in Zizers.

That’s more or less the plot: Our loser’s sister (whom he sought to control and constrain and confine) elopes to Switzerland to marry a Swiss millionaire. This is the proverbial last straw for Wertheimer, whose dream of being a great piano player was decimated the moment he heard Glenn Gould play piano years ago when they attended a conservatory together.

5. That’s like, the Glenn Gould of course—which is what our narrator calls him (that is, the).

Glenn Gould’s perfection—or rather the perfection Wertheimer (and the narrator, through whom Wertheimer lives (as a voice)) affords GG—stymies the pair forever:

Glenn is the victor, we are the failures

GG is their ideal, and the ideal shatters them:

. . . always Glenn Gould at the center, not Glenn but Glenn Gould, who destroyed us both, I thought.

And later:

. . . there’s nothing more terrible than to see a person so magnificent that his magnificence destroys us . . .

6. Glenn Gould has the gall to die of a stroke, upsetting Wertheimer to no end. (Wertheimer’s not upset that Glenn Gould has died—no, he can’t stand the perfection of Glenn Gould’s death)

7. Glenn Gould’s own idealism:

. . .to be the Steinway itself . . .

—an idealized self-erasure; a self that doesn’t think, that doesn’t theorize; a self that only acts.

8. Glenn Gould’s perfection shatters Wertheimer, but when his sister leaves him he starts to go insane:

We have an ideal sister for our needs and she leaves us at exactly the wrong moment . . .

9. More on our loser Wertheimer:

Do you think I could have become a great piano player? he asked me, naturally without waiting for an answer and laughing a dreadful Never! from deep inside.

—and—

. . . ultimately he was enamored of failure . . .

—and—

. . . he was addicted to people because he was addicted to unhappiness.

—and—

My constant curiosity got in the way of my suicide, so he said, I thought.

10. In that last example, we see the layering of The Loser’s narrative: “so he said, I thought.” The novel is entirely the narrator’s internal monologue, moving through time and space freely—yet Bernhard constantly anchors the monologue in these layered attributions. The effect is often jarring, as we experience the narrator move from memory to thought to observation on the present continuous world he is currently experiencing.

Here’s an example:

Parents know very well that they perpetuate their own unhappiness in their children, they go about it cruelly by having children and throwing them into the existence machine, he said, I thought, contemplating the restaurant.

We move from Wertheimer’s observation about throwing children into the “existence machine” to attribution of that thought to Wertheimer (“he”) to another layering of attribution (“I thought”) and then, bizarrely, to the narrator suggesting that he is “contemplating the restaurant” (the narrator’s concrete action for the first half of the book is entering an inn). The narrator simultaneously remembers and observes and contemplates—but there’s a deep anxiety here, I think, a refusal to slow down, to reflect.

11. Or perhaps this is just how “the existence machine”—consciousness—works.

12. More on “the existence machine”:

We exist, we don’t have any other choice, Glenn once said.

—and—(thus Wertheimer):

. . . we don’t exist, we get existed . . .

—and—-

Wertheimer had to commit suicide, I told myself, he had no future left. He’d used himself up, had run out existence coupons.

Existence coupons!

13. If you do not find the citation above (re: “existence coupons”) particularly and absurdly and perhaps cruelly funny, it is likely that you will not enjoy The Loser, a book that I found hilarious.

14. Another humorous passage—our narrator, having entered his “deterioration process,” elects to give away his piano:

I knew I was giving up my expensive instrument to an absolutely worthless individual and precisely for that reason I had it delivered to the teacher. The teacher’s daughter took my instrument, one of the very best, one of the rarest and therefore most sought after and therefore also most expensive pianos in the world, and in the shortest period imaginable destroyed it, rendered it worthless.

15. The Loser, like Correction, is very much about destruction, about breaking down both objects and ideas into a pure, idealized zero.

Take Wertheimer’s book, which echoes the narrator’s piano (and Glenn Gould’s own will to remove himself from the process of playing, to be “the Steinway itself”):

He wanted to publish a book, but it never came to that, for he kept changing his manuscript, changing it so often and to such an extent that nothing was left of the manuscript, of which finally nothing remained except the title, The Loser.

The narrator too plans to write a book, his Glenn Essay:

. . . everything we write down, if we leave it for a while and start reading it from the beginning, naturally becomes unbearable and we won’t rest until we’ve destroyed it again, I thought. Next week I’ll be in Madrid again and the first thing I’ll do is destroy my Glenn Essay in order to start a new one, I thought, an even more intense, even more authentic one, I thought. For we always think we are authentic and in truth we are not.

This is how idealism plays out in The Loser: a process of correction that leads to fragmentation, deterioration, nullification.

The fight against getting existed.

16. The Loser’s narrator repeatedly brings up the clash between idealism (theory) and existence (practice):

In theory he mastered all the unpleasantness of life, all the degrees of desperation, the evil in the world that grinds us down, but in practice he was never up to it. And so he went to pot, completely at odds with his own theories, went all the way to suicide, I thought, all the way to Zizers, his ridiculous end of the line, I thought. In theory he had always spoken out against suicide, deemed me capable of it however without a second thought, always went to my funeral, in practice he killed himself and I went to his funeral. In theory he became one of the greatest piano virtuosos in the world, one of the most famous artists of all time (even if not as famous as Glenn Gould!), in practice he accomplished nothing at the piano, I thought.

There is something simultaneously absurdly hilarious and tragic in the idea that even in his theoretical ideal state, Wertheimer is still not as accomplished as Glenn Gould!

17. For the narrator of The Loser, the tragic space between theory and practice is a deeply existential problem, the problem of the individual consciousness’s relation to other people:

In theory we understand people, but in practice we can’t put up with them, I thought, deal with them for the most part reluctantly and always treat them from our own point of view. We should observe and treat people not from our own point of view but from all angles, I thought, associate with them in such a way that we can say we associate with them so to speak in a completely unbiased way, which however isn’t possible, since we actually are always biased against everybody.

18. Watching some beer-truck drivers in the inn, the narrator undertakes a thought experiment that highlights a will to belong, to relate to others, coupled with the immediate dismissal—the internalized abject rejection—of this idea:

Again and again we picture ourselves sitting together with the people we feel drawn to all our lives, precisely these so-called simple people, whom naturally we imagine much differently from the way they truly are, for if we actually sit down with them, we see that they aren’t the way we’ve pictured them and that we absolutely don’t belong with them, as we’ve talked ourselves into believing, and we get rejected at their table and in their midst as we logically should get after sitting down at their table and believing we belonged with them or we could sit with them for even the shortest time without being punished, which is the biggest mistake, I thought.

19. Note in the later passages of The Loser ( including the two I cite in points 17 and 18) the dominant use of the pronoun we. The narrator’s we might be a simple rhythmic projection, a generalization of the narrator’s own anxieties displaced onto others. At the same time, the narrator’s we seems to hold the ghosts of Glenn Gould and Wertheimer, who possess, haunt, and ventriloquize the narrator’s voice—which is the novel, of course.

20. The Loser seems like a great starting place for someone interested in reading Bernhard. I think it’s a more manageable introduction to his themes than Correction is: the humor is more accessible, the book’s ironies perhaps more apparent, and its sentences are far, far shorter. (I feel the need to clarify: None of these comments should be interpreted as a knock against Correction, which I thought brilliant; neither should these comments be interpreted as a knock against the intelligence and abilities of readers interested in Bernhard).

21. I still have two Bernhards in the stack—Yes and Concrete—but I’ll hold off for a while. Dude’s writing is rewarding but taxing.

“He was an aphorism writer” (Thomas Bernhard)

He was an aphorism writer, there are countless aphorisms of his, I thought, one can assume he destroyed them, I write aphorisms, he said over and over, I thought, that is a minor art of the intellectual asthma from which certain people, about all in France, have lived and still live, so-called half philosophers for nurses’ night tables, I could also say calendar philosophers for everybody and anybody, whose sayings eventually find their way onto the walls of every dentist’s waiting room; the so-called depressing ones are, like the so-called cheerful ones, equally disgusting.

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel The Loser.

“All schools are bad” (Thomas Bernhard)

All schools are bad and the one we attend is always the worst if it doesn’t open our eyes. What lousy teachers we had to put up with, teachers who screwed up our heads. Art destroyers all of them, art liquidators, culture assassins, murderers of students.

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel The Loser.

Reading-as-Nature or Nature-as-Reading (From Thomas Berhnhard’s Correction)

We couldn’t endure a life in nature, necessarily always a free nature, without respite, so we always step outside nature, for no reason but survival, and take refuge in our reading, and live for a long time in our books, a more undisturbed life. I’ve lived half my life not in nature but in my books as a nature-substitute, and the one half was made possible only by the other half. Or else we exist in both simultaneously, in nature and in reading-as-nature, in this extreme nervous tension which as a form of consciousness is endurable only for the shortest possible time span. The question can’t be whether I live in nature as nature, or in reading-as-nature, or in nature-as-reading, in the nature of nature-as-reading andsoforth, so Roithamer. To everything that we think and fill our own life and that we hear and see, perceive, we always have to add: the truth, however, is … as a result, uncertainty has become a chronic condition with us. Those abrupt transitions from one nature into the other, from one form of awareness into the other, so Roithamer. When we think, we know nothing, everything is open, nothing, so Roithamer.

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Correction.