Joshua Henkin’s new novel, The World Without You, tells the story of the Frankels, a large Jewish American family who gather over the Fourth of July weekend to mourn the death of their son Leo, a journalist who was kidnapped and then murdered in Iraq. The World Without You is Henkin’s third novel after Matrimony and Swimming Across the Hudson. Henkin directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The World Without You is new in hardback from Pantheon. You can learn more about Henkin at his website. He was gracious enough to talk to me over a series of emails about writing, teaching, verb tense, sympathy, and his new novel.

Joshua Henkin’s new novel, The World Without You, tells the story of the Frankels, a large Jewish American family who gather over the Fourth of July weekend to mourn the death of their son Leo, a journalist who was kidnapped and then murdered in Iraq. The World Without You is Henkin’s third novel after Matrimony and Swimming Across the Hudson. Henkin directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The World Without You is new in hardback from Pantheon. You can learn more about Henkin at his website. He was gracious enough to talk to me over a series of emails about writing, teaching, verb tense, sympathy, and his new novel.

Biblioklept: There’s a lot going on in The World Without You, but it seems to be essentially a novel about a family—what it means to be a family, what it means to be in a family, what it means to be in conflict with a family—where did the Frankels come from?

Josh Henkin: The most simple answer is, My imagination. The Frankels aren’t based on anyone I know, and like all characters in fiction (at least the kind of fiction I write), they developed slowly over time; I discovered them in the writing process over the course of quite a number of years. What I would say is that I think that in the same way that people speak of “rebound relationships,” I think of my novels as “rebound novels.” Matrimony took place over twenty years and focuses on a small cast of characters, and I wanted to write something different this time. So, whether consciously or not, I set out to write a book that was more compressed, on one hand (it takes place over 72 hours instead of over 20 years), and more spacious, on the other hand (there are many more characters, and we go into many points of view). If you’re asking where the inspiration for the book came from, I’d say it came mostly from the following. I had a first cousin who died of Hodgkin’s disease when he was in his late twenties. I was only a toddler at the time, but his death hung over my extended family for years. At a family reunion nearly thirty years later, my aunt, updating everyone on what was happening in her life, began by saying, “I have two sons….” Well, she’d once had two sons, but her older son had been dead for thirty years at that point. It was clear to everyone in that room that the pain was still raw for her and that it would continue to be raw for her for the rest of her life. By contrast, my cousin’s widow eventually remarried and had a family. This got me thinking how when someone loses a spouse, as awful as that is, the surviving spouse eventually moves on; but when a parent loses a child they almost never move on. That idea was the seed from which The World Without You grew. Although there are many tensions in the novel (between siblings, between couples, between parents and children), the original tension was between mother-in-law and daughter-in law, caused by the gulf between their two losses, by the different ways they grieve.

Biblioklept: You mention the compression of The World Without You, which here strikes me as form of realism. The book takes place over the July 4th holiday—why did you choose this setting? Was the Independence Day setting always part of your design?

JH: I knew I wanted a compressed period of time–mostly because Matrimony took place over twenty years and I think of books like relationships: one book is a rebound from the previous one. I also knew that I wanted the book to be told in many points of view; this, too, makes it different from Matrimony, which was told only in Julian and Mia’s points of view. In terms of Independence Day, I think that was a little more unconscious, though probably intentional as well. Part of the issue was a practical one: how do you get a large, disperse family together in one place? You need an occasion for the telling, and a holiday like July 4th provides one. Though of course the real occasion for the telling is Leo’s memorial. But I think even there Independence Day is relevant because although the book is obviously about the specific characters (I think all fiction worth its salt is always first and foremost about the particular, not the general), I do think this novel in its own indirect way is a novel about America more broadly, and certainly about a certain segment of America, of which I consider myself a part. The Frankels are a political family, with strong opinions about Bush and about the Iraq War, but they’re also privileged. They’ve really known no one who has fought in the war, have been insulated from it in their day-to-day lives–and then, with Leo’s death, it comes and touches them in the most horrific and personal way. And I wondered what that’s like–to be mourning while the rest of the country is celebrating, to be commemorating the independence of a country that has sent its young men and women to war, a country that’s responsible for their son and brother’s death.

Biblioklept: You mention the Frankels’s privileged background. They are, for the most part, liberal, secular, refined. Leo dies in Iraq, but, significantly, he’s a journalist, not a soldier. Do you worry that not all readers will connect to these characters? How do you make your characters sympathetic—or does sympathy even matter in fiction?

JH: My feeling is that people are people, and they merit as little or as much sympathy as they merit whether they’re rich or poor, healthy or sick, beautiful or ugly. There’s a strand of anti-elitism in American culture (one can see it every day, tirelessly, in our politics), and one sees it, too, in certain attitudes toward literature–the idea being that only the humble, the uneducated are worthy of our fiction. But I find the idea pretentious; it smacks of a kind of reverse snobbery. And tell it, in any case, to Fitzgerald, or Cheever, or Yates. One of the things good literature does is it humanizes people we might not otherwise be drawn to. And (this is at least as important) it allows us to enjoy the company of people on the page whose company we might not enjoy off the page. Which is another way of saying that sympathy doesn’t matter in fiction, at least not sympathy narrowly construed. In fiction, as in life, some people are likable and some people aren’t likable, and the world would be boring if everyone were likable. The fiction writer’s job is to make his characters complex, interesting, fully human, not (or at least not necessarily) likable.

Biblioklept: The World Without You is conveyed in the present tense. I’m curious what led you to compose in the present tense, or if you drafted parts of the novel in the past tense—what advantages can the present tense offer the writer and reader? What are its limitations?

Biblioklept: The World Without You is conveyed in the present tense. I’m curious what led you to compose in the present tense, or if you drafted parts of the novel in the past tense—what advantages can the present tense offer the writer and reader? What are its limitations?

JH: I think about tense a lot, probably because I teach fiction writing and, more specifically, because I direct Brooklyn College’s Fiction MFA program, and so I end up reading 500 application manuscripts a year, a good number of which are written in the present tense. It’s said that present tense makes the story feel more immediate, yet year after year I notice among our graduate applications that the present-tense stories are usually the least immediate, most inert stories in the bunch. Why is that? I think it’s because some writers use present tense as a substitute for narrative, as a way of hiding that nothing is happening in their stories. They think that if they write in present tense their stories will feel immediate.

I also think that present tense is deceptive because it’s easy in present tense to slip out of scene and into general/habitual time. In the past tense, you would write “She went to the store on Tuesday” to suggest that the character is going to the store at a specific time. If, on the other hand, you wanted to indicate repeated or habitual action, you would write, “She would go to the store on Tuesday.” But in the present tense there generally isn’t such a distinction between the specific and the habitual. “She goes to the store on Tuesday” can mean either that she’s going to the store right now on Tuesday or that she’s a habitual store-goer on Tuesdays. I think what happens in present tense is that a lot of writers end up slipping into the habitual, and so what seems immediate is actually not at all immediate.

The other thing I’d say is that it’s very hard to write a present-tense novel that takes place over ten years because it’s likely to feel artificial for all that time to be in present tense. Present tense works best, then, in novels and stories told in compressed time.

The World Without You simply came to me in present tense. That was the tense that felt right for the book. This may be true, in part, because I’d been influenced by Richard Ford’s Independence Day, another novel told over a single July 4th holiday that’s told in present tense. But I think it’s more than that. The World Without You takes place over 72 hours, so it’s ideally suited for present tense, and it’s also told in confined space; most of the book is situated in the Frankel family home and the streets that surround it in Lenox, Mass. One thing I was trying to do was balance the sprawling quality of the book (there are many characters and lots of different points of view) with the more focused time and space that I just mentioned, and I think present tense allowed me to do that. But all this is post-facto, a case of me looking back at what I did. I proceeded intuitively, which is what I always do, and present tense simply felt right (it was the right sound, the right voice) for this book.

Biblioklept: You bring up your position as Brooklyn College’s MFA fiction program director—I’m curious if reading so many manuscripts affects your own writing.

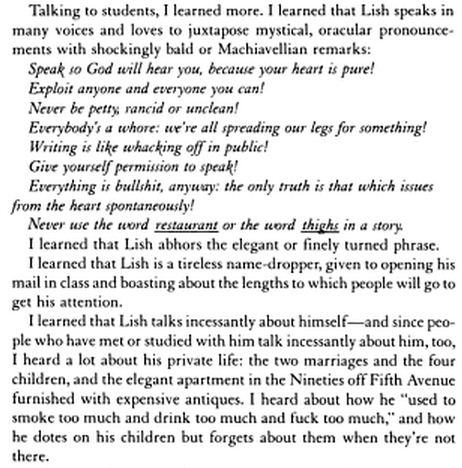

JH: I love teaching, and that’s in large part because I get to teach some of the most talented young writers out there. In the last few months alone, five of our recent MFA graduates have gotten book contracts. There are writers who wouldn’t know how to teach; for them, writing is an intuitive process and they aren’t fully conscious of what they’re doing. For me, it was the opposite. I could read someone else’s short story and figure out what wasn’t working long before I could make things work in my own stories. I needed to learn how to become a more intuitive writer, and critiquing other people’s stories helped me do that; it still helps me. I’ve been at this process longer than my students have, but we’re all struggling with the same thing—how to write convincing stories; how to make our characters comes so deeply to life they feel as real as, even realer than, the actual people in our own lives; how to use language in a way that’s precise and beautiful and utterly true. That never changes. So in a way, even though I’m the instructor, we’re all students in the room. Also, I’m a fairly social person, and writing is incredibly solitary, so teaching gives me the chance to be with other people and to talk about the work I love.

Biblioklept: Are there manuscripts that come in where you just kind of slap your forehead and go, “Not another story about ______ again!”

JH: Absolutely. Many of my graduate students are in their mid-twenties, and so they write about the concerns of people in their mid-twenties. How to find love in the big city, that kind of thing. That’s okay. If it’s done well, just about any subject matter can make for compelling fiction, and in any case, my students won’t be in their mid-twenties forever. That’s one of the nice things about being a writer. You mature; you get better over time. Writing is different from figure skating. It’s even different from playing the violin. You can be in your late forties and still be a young writer. At least that’s what I like to tell myself!

Often it’s less a similarity of subject matter that I see than a similarity of voice or sensibility. For a time I saw a lot of Lorrie Moore imitators. Then I saw a lot of George Saunders imitators. If you’re going to imitate someone, those are two pretty good choices, though in a lot of ways Moore and Saunders are inimitable. But that’s fine. Imitation is part of the maturing process. It’s how a writer achieves her own voice.

Biblioklept: Do you have any upcoming writing projects? What are you working on next?

JH: My most immediate project is a trip to Hawaii! Writing a novel takes a lot out of you. Right now, I’m trying to figure out what comes next. I promised myself I would go back to writing short stories. It’s weird, I’ve spent the last nearly twenty years writing novels, when in so many ways I think of myself as a short-story writer. It was certainly my first love, and because I teach MFA students, I spend a lot of time reading and thinking about short stories. So last fall, when I finished the final draft of The World Without You, I immediately sat down to write a short story, and what happened? The draft I wrote was 113 pages along! And then the second short story I wrote was over 200 pages long! I still think I’m capable of writing a regular old twenty-to-thirty-page short story, but we’ll have to see. In the meantime, I’m tossing around some ideas for a new novel, but it’s still in the very early, incubating stages, so I’m not saying anything more than that.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

JH: Alas, I have not. But I’m working on it.

Joshua Henkin’s new novel, The World Without You, tells the story of the Frankels, a large Jewish American family who gather over the Fourth of July weekend to mourn the death of their son Leo, a journalist who was kidnapped and then murdered in Iraq. The World Without You is Henkin’s third novel after Matrimony and Swimming Across the Hudson. Henkin directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The World Without You is new in hardback from

Joshua Henkin’s new novel, The World Without You, tells the story of the Frankels, a large Jewish American family who gather over the Fourth of July weekend to mourn the death of their son Leo, a journalist who was kidnapped and then murdered in Iraq. The World Without You is Henkin’s third novel after Matrimony and Swimming Across the Hudson. Henkin directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The World Without You is new in hardback from  Biblioklept: The World Without You is conveyed in the present tense. I’m curious what led you to compose in the present tense, or if you drafted parts of the novel in the past tense—what advantages can the present tense offer the writer and reader? What are its limitations?

Biblioklept: The World Without You is conveyed in the present tense. I’m curious what led you to compose in the present tense, or if you drafted parts of the novel in the past tense—what advantages can the present tense offer the writer and reader? What are its limitations?