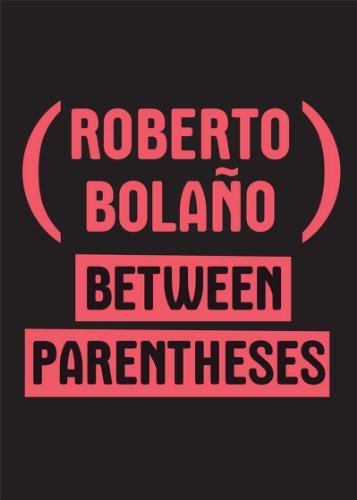

Between Parentheses (new from New Directions and deftly translated by Natasha Wimmer) collects over 400 pages of Roberto Bolaño’s essays, speeches, introductions, and newspaper columns, composed between 1998 and 2003, the year Bolaño died. The bulk of the book, as well as its title, comes from a column that Bolaño wrote for the Chilean newspaper Las Últimas Noticias. As one would expect, these pieces are relatively short, sometimes under 500 words, punctuated with a depth that belies their brevity. Bolaño writes about everything (or, everything worth writing about, I suppose), but, as those familiar will guess, literature is his main subject, whether he’s reviewing a Spanish-language translation of McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, comparing Kafka and Philip K. Dick, explaining his affection for William Burroughs, or discussing the merits of translating literature. If these samples tantalize you, let me go further: Bolaño writes about detective novels, Walter Mosley, Jonathan Swift, Jorge Luis Borges, magic, devils, memoirs, Gunter Grass, murder, troubadours, the Hell’s Angels, poetry, and more, more, more.

Despite its discursive topics, a unified tone inheres throughout Between Parentheses, a distinctly Bolañonian tone, at once grand and romantic (and Romantic) and profound and cynical and biting and flippant. In her blurb on the back of the book, Marcela Valdes (The Nation) declares that in Between Parentheses “we hear Bolaño’s real voice, the one he often disguised through the ventriloquism of his fiction.” This is perhaps a too-bold statement—I’m not sure if Bolaño can be said to have a “real voice”—instead, we find an author who’s constantly inventing and then reinventing, inflating and deflating, expanding and contracting.

And yet I think we’ll have to take Between Parentheses as Bolaño’s “real voice”—it’s perhaps the closest thing we’ll get to memoir or autobiography from the man (at least for now: his literary estate seems to be in a constant state of excavation, so who knows). But Bolaño, ever the winking imp, is there to warn us against taking memoir at face value—

Of all books, memoirs are the most deceitful because the pretense in which they engage often goes undetected and their authors are usually only looking to justify themselves. Ostentation and memoirs tend to go together. Lies and memoirs get along swimmingly.

If Bolaño may occasionally employ invention in some of the passages here, it’s all to his credit, and all perhaps in the service of Higher Artistic Truth (whatever that means). He shares much of himself in Between Parentheses, especially in the book’s first section, “Three Insufferable Speeches,” (you may have already read “Literature and Exile”) and its second section, “Fragments of a Return to the Native Land,” detailing the writer’s return to Chile in 1998. These are indeed fragments, sketchy, pained moments where we glimpse Bolaño trying to process a difficult and emotional journey. The tone is at once comic, analytical, and depressive—familiar territory to Bolaño’s readers, I suppose. Besides its obvious appeal as a Bolaño memoir, “Fragments” is also fine travel literature, as is the later section “Scenes,” which comprises evocations of various locales, chief among them Bolaño’s adopted home Blanes. Several of the pieces in “Scenes” seem to extend into the realm of pure fiction; a few are narrated by speakers who are only partly-Bolaño (if such a construction can be said to exist). In any case, they are the book’s closest approximations of short fiction.

The book’s fifth section, “The Brave Librarian,” features one of the highlights (and longer pieces) of the volume, a preface for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn called “Our Guide to the Abyss,” where Bolaño parses Twain and Melville, delving into American literature. I’m sure that for many this piece alone will be worth the price of admission. If you still need convincing, the book’s final section offers a treatise on book theft, advice on the art of writing short stories, a transcript of Bolaño’s last interview before his death, and more, more, more. “More, more, more” might be a simple way to summarize this book.

Between the Parentheses does little, ultimately, to explicate Roberto Bolaño. If anything, it helps to further confound those of us who’ve been puzzling out his fiction for the past few years. And thank God for that. I’ve written before about “the Bolañoverse,” about Bolaño’s labyrinthine genre-crossing intertextuality. Between Parentheses, despite its claims to reality or truth, is nevertheless a part of Bolaño’s maze, a maze by turns dark or illuminating, tragic or comic, and stark and enriching. Most of all, this maze is a strange joy to get lost in. Highly recommended.