- Robert Walser

- Franz Kafka

- Henry Miller

- Thomas Bernhard

- David Markson

- Renata Adler

- W.G. Sebald

- Lydia Davis

- Ben Marcus

1. I’ve been rewatching David Simon’s Baltimore epic The Wire, generally regarded as one of the best if not the best, TV series ever. I’ve been watching with my wife, who’s never seen the show before. I’m going to riff on a few of the themes of season four of The Wire here, and there will be spoilers.

If you’ve never seen The Wire and you think that some day you want to see it (it’s as good as everyone says it is, so you should want to see it) you shouldn’t read this post because of the spoilers.

2. Season four of The Wire takes education as its central subject. Specifically, it examines the different ways in which personal circumstance and chance (and maybe fate) intersect with institutions. The simplest example of one of these institutions might be Edward J. Tilghman Middle School, but there are other institutions too—the city’s political core, including the Mayor and his advisers, the police and their various detention centers, and even the criminal organizations that foster their own trainees.

3. Season four gives us four eighth graders to care about. The first episode of the season, “The Boys of Summer,” establishes these characters as they prepare to head from childhood into a more complex—and violent—world:

Childish joy and youthful agitation mixes with real territorial violence here; everything that follows in the season shades this scene with a bleak irony.

4. Season four presents a series of possible mentor relationships, wherein various principal characters contend to steward, foster, educate, or otherwise help these four kids turn into four men.

Roland Pryzbylewski, one-time detective-cum-fuck-up, becomes the teacher Mr. Presbo. He idealistically tries to help the four kids, who all take his class together. Parallel to Pryzbylewski’s efforts in the classroom are Dennis “Cutty” Wise’s efforts in the boxing gym; he hopes to take these kids off the corners as well. Initially, Presbo fosters Randy and Dukie while Cutty tries to make headway with Namond and Michael.

As the season develops, different mentors present themselves for each of the kids. Almost all fail.

Cutty loses whatever inroads he had on mentoring Michael, who comes under the tutelage of the dark assassin Chris. Tellingly, Michael enlists Chris in killing off his brother Bug’s father; the assassination is Oedipal.

Mr. Presbo helps Dukie in real and meaningful ways, making sure that the indigent child has clean clothes and a place to shower, but also showing him a kind of loving respect wholly absent in his relationship with “his people,” hopeless, horrible drug addicts. However, after Dukie is promoted to high school early, Mr. Presbo realizes that he will have to limit his involvement with the boy. He sees that there will always be another Dukie to come along, and that he can’t “keep” the boy—only steward him for a year or two.

After a series of institutional bungles, Carver tries to protect Randy, but loses him to a group home. The last time we see Randy he receives a savage beating at the hands of his roommates.

5. (I should now bring up Sherrod, a dim bulb of maybe 15 who seems to have dropped out of school years ago. Homeless, he’s “schooled” by Bubbles, who first tries to make him return to Tilghman, and then, seeing the boy won’t go, tries to teach him some basic survival skills. Sherrod ends up dead though, and Bubbles, feeling that the death is his fault (which it is in part), attempts suicide. Another failed mentor.

We can also bring up Bodie, whom McNulty attempts to help, albeit the relationship here is hardly on the mentor/avuncular (which is to say, displaced father/son) axis that the other five boys experience. Still, McNulty tries to steer Bodie to a path that would help absolve the young man’s conscience. The path leads to the young man’s murder).

6. And Namond?

Namond is perhaps the most fascinating figure in season four, at least for me. He’s a spoiled brat, hood rich, the son of infamous Barksdale enforcer Wee-Bey Brice who is doing life for multiple murders. Namond is petulant and mean and immature. He bullies Dukie, yet he doesn’t have the “heart” (in the series’s parlance) to manage selling drugs on his corner, a weakness that comes to harsh light when a child of no more than eight steals his package of drugs. Namond is a mama’s boy, but bullied by an overbearing mother, a woman who encourages him to drop out of school to sell drugs for her own material comfort. He is not made of the same stuff as his father.

Namond is also creative, funny, charismatic, individualistic, and intelligent. Bunny Colvin sees these qualities and sees an opportunity to help—to really help—one person. And here is the moment of consolation in season four. It’s a consolation for Colvin, who has experimented twice now with programs that bucked the institutional path (Hamsterdam in season three; the corner kids project in season four), and perhaps it’s a consolation for Cutty, who is instrumental in connecting Colvin with Wee-Bey. But it’s also a consolation for the audience, who perhaps will concede that one out of four ain’t bad. (Although clearly, three out of four children are left behind).

7. The Wire’s emphasis on Baltimore locations, specific regional dialects, and its use of local, semi-professional actors afforded the show a strong sense of realism. Straightforward shots and short scenes added to this realism. What I perhaps like most about The Wire’s realism is its near-complete lack of musical cues: other than the opening song and closing credits soundtrack, the only music that appears in any scene in The Wire is internal to the scene, i.e., we only hear music if the characters are hearing it (in their cars, on their stereos, etc. — a la rule two of Dogme 95).

The Wire breaks from these formal realistic conventions at the end of each season, using a montage—a device it almost always avoids—overlaid with a song. Here’s the montage from the end of season four:

8. I include the montage as a means to return to point 6, Namond. The images unfold, giving a sense of where our characters (those who survive season four) will go next (the universe of The Wire is never static; our characters are always in motion). The montage settles (about 4:40 in the video above) to rest on Namond, working on his homework, clearly more comfortable if not at ease in his new life with the Colvins. A family embraces on the porch of the house behind the Colvin house, signaling that Namond has finally arrived in an institution that can protect and foster and nourish him—a loving family. A reminder of his old life as a corner boy enters the scene as the young car thief Donut pulls up, smiling; there’s an implicit offer to return to the corner life here. Then Donut blazes through a stop sign, almost causing a wreck. Namond’s troubled face signals that he’s learned something, but it also twists into a small grin. The shot lingers on the crossroads: open possibility, but also the burden of choice.

9. (Parenthetical personal anecdote that illustrates why season four is, for me, easily the most emotionally affecting entry in The Wire:

For seven years I taught at an inner city high school that was plagued by low test scores, low student interest, and violence. The school’s population was about 95% black, with most students receiving free or reduced lunch. I was still working at this school when I first saw The Wire’s Edward J. Tilghman Middle School, and although the depiction was hyperbolic in places, the general tone of chaos and apathy was not at all unfamiliar to me. There were fights at my school. Brawls. Gang violence. Murders even—student-on-student murders that still haunt me today (these didn’t happen on campus, but they were still our students). I recall one day leaving early—I had fourth period planning and my principal allowed me to leave once a week to attend a graduate school course—and being stunned to see two swat trucks pull up around the school and unload teams of militarized police.

Most of our students were good people trying to get a good education despite very difficult circumstances that were beyond their own control—poverty, unstable family environments, severe deficits in basic skills like reading and math. And most of our teachers were good people trying to help these students as best as they knew how in spite of a draconian, top-heavy management structure that emphasized the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT) as the end-all be-all of education.

I’m tempted here to rant about tests like the FCAT and legislation like the No Child Left Behind Act, rant about how they drain schools of resources, rob children of a true education, and limit teachers’ and schools’ ability to differentiate instruction—but that’s not the point of this riff.

Probably more productive to let The Wire illustrate. I’ve sat in meetings like this one (I imagine many educators have):

The primary goal of the institution is always to maintain the institution, no matter what the mission statement might be.

What I’m trying to say here is that The Wire’s Edward J. Tilghman Middle School strikes me as very, very real).

10. I’ll conclude by returning to Namond and Colvin and suggest that this is the closest thing to a happy ending that The Wire could possibly produce. The Wire perhaps boils down to the evils of institutionalism (of any kind); Colvin (and, to be fair, Cutty and Wee-Bey to a certain extent) must take an individualistic response to bypass institutional evils. (In season five, McNulty will carry out an individualistic response to institutional apathy—which is to say practical evil—on a whole new level).

The Wire plainly shows us that life costs, that all decisions cost, and that decisions cost in ways that we cannot calculate or measure or foresee. Namond’s future comes at the cost, perhaps, of Michael, Dukie, and Randy, the children who are left behind. And here is the real evil of a mantra like “no child left behind”—its sheer meaningless as a philosophy inheres in its essentially paradoxical nature, whereby if no single child can be left behind then all children can be left behind—the institution simply redefines or “jukes” what “behind” means. Colvin’s solution, on one hand, is to pragmatically assess the costs and payoffs of managing his interest in education, in being “a teacher of sorts” (as he calls it). (This pragmatic side echoes his Hamsterdam experiment in season three). Colvin’s pragmatism is successful though not only because he realizes his limitations—he cannot help just any child, and certainly not every child—it is also successful because it is tempered in love.

“That wasn’t quite my contention,” he began simply and modestly. “Yet I admit that you have stated it almost correctly; perhaps, if you like, perfectly so.” (It almost gave him pleasure to admit this.) “The only difference is that I don’t contend that extraordinary people are always bound to commit breaches of morals, as you call it. In fact, I doubt whether such an argument could be published. I simply hinted that an ‘extraordinary’ man has the right… that is not an official right, but an inner right to decide in his own conscience to overstep… certain obstacles, and only in case it is essential for the practical fulfilment of his idea (sometimes, perhaps, of benefit to the whole of humanity). You say that my article isn’t definite; I am ready to make it as clear as I can. Perhaps I am right in thinking you want me to; very well. I maintain that if the discoveries of Kepler and Newton could not have been made known except by sacrificing the lives of one, a dozen, a hundred, or more men, Newton would have had the right, would indeed have been in duty bound… to eliminate the dozen or the hundred men for the sake of making his discoveries known to the whole of humanity. But it does not follow from that that Newton had a right to murder people right and left and to steal every day in the market. Then, I remember, I maintain in my article that all… well, legislators and leaders of men, such as Lycurgus, Solon, Mahomet, Napoleon, and so on, were all without exception criminals, from the very fact that, making a new law, they transgressed the ancient one, handed down from their ancestors and held sacred by the people, and they did not stop short at bloodshed either, if that bloodshed—often of innocent persons fighting bravely in defence of ancient law—were of use to their cause. It’s remarkable, in fact, that the majority, indeed, of these benefactors and leaders of humanity were guilty of terrible carnage. In short, I maintain that all great men or even men a little out of the common, that is to say capable of giving some new word, must from their very nature be criminals—more or less, of course. Otherwise it’s hard for them to get out of the common rut; and to remain in the common rut is what they can’t submit to, from their very nature again, and to my mind they ought not, indeed, to submit to it. You see that there is nothing particularly new in all that. The same thing has been printed and read a thousand times before. As for my division of people into ordinary and extraordinary, I acknowledge that it’s somewhat arbitrary, but I don’t insist upon exact numbers. I only believe in my leading idea that men are in general divided by a law of nature into two categories, inferior (ordinary), that is, so to say, material that serves only to reproduce its kind, and men who have the gift or the talent to utter a new word. There are, of course, innumerable sub-divisions, but the distinguishing features of both categories are fairly well marked. The first category, generally speaking, are men conservative in temperament and law-abiding; they live under control and love to be controlled. To my thinking it is their duty to be controlled, because that’s their vocation, and there is nothing humiliating in it for them. The second category all transgress the law; they are destroyers or disposed to destruction according to their capacities. The crimes of these men are of course relative and varied; for the most part they seek in very varied ways the destruction of the present for the sake of the better. But if such a one is forced for the sake of his idea to step over a corpse or wade through blood, he can, I maintain, find within himself, in his conscience, a sanction for wading through blood—that depends on the idea and its dimensions, note that. It’s only in that sense I speak of their right to crime in my article (you remember it began with the legal question). There’s no need for such anxiety, however; the masses will scarcely ever admit this right, they punish them or hang them (more or less), and in doing so fulfil quite justly their conservative vocation. But the same masses set these criminals on a pedestal in the next generation and worship them (more or less). The first category is always the man of the present, the second the man of the future. The first preserve the world and people it, the second move the world and lead it to its goal. Each class has an equal right to exist. In fact, all have equal rights with me—and vive la guerre éternelle—till the New Jerusalem, of course!”

From Chapter V of Part III of Dostoevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment.

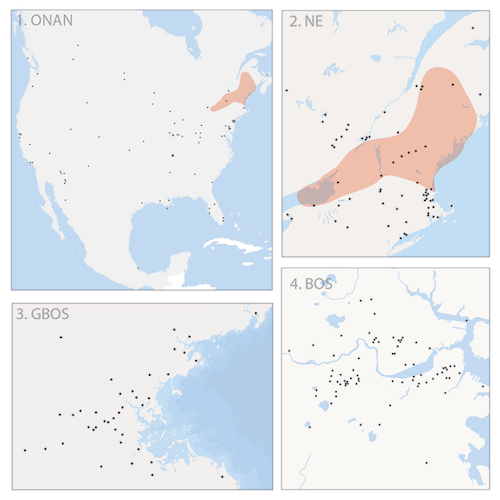

For the past few years, D.C.-based artist William Beutler has been mapping the real and fictional locations of David Foster Wallace’s giant novel Infinite Jest in a project called Infinite Atlas, a Google Maps-based guide to over 600 locations described in Infinite Jest. Beutler’s project has sprawled (appropriately) to include several dimensions, including Infinite Map (shown above), which identifies and describes 250 locations from the novel and Infinite Boston, a travel blog of sorts that documents and reflects on Beutler’s Wallace-based trip to Boston. Beutler was kind enough to talk to me about his projects over a series of emails.

Biblioklept: How did the Infinite Atlas project start?

William Beutler: I think, like a lot of long-term projects, I’d point to a few different points of inspiration. The first is just going back and reading Infinite Jest for a second time in 2009, after I’d say it went from being a favorite novel to my actual favorite novel. I’d also become interested in infographics, I suppose as a kind of art form based on the expression of data—and what better stockpile of data than a thousand-page, encyclopedic novel? I cycled through a lot of ideas, finding that some of them had already been done before, and then finally deciding to focus on geography.

Biblioklept: How did the geography focus come about?

WB: The geography focus owes to a few different things. One is simply that I wasn’t the first to arrive at the idea of creating an infographic based on Infinite Jest, so I had to take that into consideration. Sam Potts, who is the designer of John Hodgman’s books, had released an elaborate graphic drawing connections between the various characters in the novel. I’d been considering that when his came out, but he did that pretty definitively, so I went with one oft he other. And hey, I just like maps. I started my career in political journalism, where districts are always being redrawn, and maps are always being shaded this much red or this much blue, so it was a natural focus in that regard. And there’s always been something I’ve liked about adding a layer of information to geographic features. I don’t know that I could have credibly called myself a geography enthusiast before this—but I have friends who definitely are, and even some who work with GIS professionally. They helped me figure out what I was doing.

Biblioklept: Did you consciously start using Google Maps? Was Google Maps a starting point in and of itself or just a tool?

WB: Google Maps was probably one of the very last decisions we made. And all the web development was relatively late in the process, starting about early summer of this year. Most of the work before that was simply building the database, which lived in Google Docs for most of this research period. The decision to use Google Maps wasn’t necessarily random, although I had actually made an early conscious decision to not use it. I’d suggested Open Street Maps, partly because I like open source projects, and Foursquare had switched to it, which seemed like a noteworthy endorsement. But my developers said Google Maps was going to be less time-consuming, and less expensive, and I was willing to take this advice.

Biblioklept: Can you talk a bit about how you put the atlas together? What was your approach? How did you start?

WB: In the very early going, it was as simple and painstaking as going page-by-page through the book, scanning each one for proper nouns, and taking notes down in Google Docs. This was myself and another friend who had read the book, Olly Ruff, who is one of the credited editorial advisers. We debated what really counted as a “location”—Orin’s “Norwegian deep-tissue therapist” lives “1100 meters up in the Superstition Mountains,” overlooking Mesa-Scottsdale. So is that one location, or two?And once we realized we had so many locations, this was about the time I realized the original idea, which was just the map, was not going to be the comprehensive accounting for the novel’s locations I had imagined. Once I decided we had to explore an interactive version as well, then we had to decide which locations were just going on the map, and how many. Then we had to figure out where certain locations were actually located, and that was a considerable amount of research as well. Sometimes it was very obvious-—Harvard Square is very easy to find, but some places I didn’t even know were real until I visited Boston. We also had to figure out how to show both the scope of North America alongside the detail of central Boston, and this just took an agonizingly long time. This is where some of my friends who worked with maps for a living proved helpful. The further into this I got, the bigger of a project it kept revealing itself to be. And since the point of no return was never clear, I just kept at it, never entirely sure how long it would all take, until we actually started working with designers.

Biblioklept: How did actually visiting Boston help to inform the project?

WB: About a year into the research, I realized that I was hitting a wall with some of the local details in Boston, which has the greatest concentration of locations of anywhere in the novel. More specifically, the neighborhoods of Allston and Brighton already kind of run together, and then Wallace invented a whole new unincorporated community called Enfield, where most of the primary characters live, and its relationship to Allston-Brighton was very confusing. The trip helped me get a better sense for what was Enfield and what was Brighton, although there’s only textual support for boundary lines to the east and south.Also regarding certain locations, I knew the Brighton Marine hospital complex was the basis for Enfield Marine, and I knew that the hill behind it was where the Enfield Tennis Academy would be, if it existed, but Google Maps and Google Street View have some pretty obvious limitations. So putting boots on the ground was really the only way to be sure about some of these places. I was surprised by some things I found: there’s a “Professional Building” mentioned as being at one intersection when it’s really another, which I had no idea until I walked right up to it. And the Infinite Boston Tumblr simply couldn’t have existed without the trip, but the trip was also absolutely necessary for getting a lot of details right for Infinite Atlas and Infinite Map.

Biblioklept: How long have you been working on the Infinite Boston blog?

WB: The Boston trip was in July 2011, and the notion of doing a Tumblr travelogue to the project was probably in the back of my head at the time, but I didn’t really start thinking about seriously doing it until earlier this year. I’d been sifting through the photos—I came back with about 4,000—since then, and in the spring I started making decisions about what I had acceptable photos of, and what I had enough to write about, then I started planning the sequence in June, and putting together notes in early July. And though I had quite a few entries planned out weeks in advance to begin with, these days I’m finishing them the night before, or up to the last few minutes before publishing.

Biblioklept: The Infinite projects clearly will resonate with fans of Wallace’s novel. What do you hope they take away from your work?

WB: I can’t begin to tell you the number of people who’ve told me they started Infinite Jest, and gave up after making it a surprisingly long way through it. One friend of mine spent the better part of a decade having read to at least page 600 before finally finishing it earlier this year. (He ended up helping out as a backup researcher.) I’ve heard it said that the book doesn’t really start coming together until about 400 pages, and it’s been much too long since I first read it for me to remember, but I know the feeling of hopelessness that goes along with struggling early in a long novel (I’m still working myself back up to revisiting Gravity’s Rainbow and Europe Central…). I think a project like this can serve as a kind of promise to the uninitiated that there really is something here that people feel very strongly about, that it rewards the effort one must put into it. There’s much more to it than just being a hipster status symbol. And then I think it can help those who are reading it, both to confirm details they may have misread the first time or—better still—to make connections they might never have made without this kind of tool. And of course to visualize it as David Foster Wallace surely did, if they’re so inclined. That said, I’m not sure the Atlas is a resource I would have consulted when I first read the book. I tend to be very spoiler-sensitive, oftentimes purposefully going into a novel or a film or television series trying to know as little as possible. Of course, I know now that Infinite Jest can’t be “ruined” by knowing about a particular story arc, and I’m sure that others so wracked with fear over knowing that two storylines connect, so I hope they’ll find this a useful resource.

Biblioklept: I’m curious if you’ve read Houellebecq’s novel The Map and the Territory?

WB: I have not actually read any Houellebecq; I’m primarily familiar with him for various controversies, and I do remember the allegations that he had plagiarized Wikipedia for The Map and the Territory, and the possibility then that his book would be judged a Creative Commons-licensed work. Anyhow, I am familiar with the map-territory relationship as described by Alfred Korzybski, and Infinite Jest was my introduction to it. I think it’s very relevant here, not that anyone would necessarily mistake the atlas as anything but a supplement to the novel. Actually, one of my early working titles for the project was “Map / Territory,” and the website includes a kind of epigraph, taken from the Eschaton section: “The real world’s what the map here stands for!”

Biblioklept: I figured the Eschaton episode clearly resonated with your project. What sections or characters of IJ stand out as favorites to you?

WB: Believe it or not, Eschaton was one of the last location segments that I added to the Atlas. Early on we’d focused on real places where scenes actually took place, or references to North American locations that fell inside the confines of the map. And Chris Ayers of Poor Yorick Entertainment had already made a pretty nifty Eschaton infographic, so I was hesitant to do too much with that. But it became clear that we were going to take a maximalist approach, and really locate absolutely everything that could be located, so then I went through and included everything from Eschaton as best I could.If I had to name a favorite section, it might be the very last, with Gately and Fackelman holed up with Mt. Dilaudid, avoiding the wrath of Whitey Sorkin. It’s just beautifully written, and for whatever criticisms anyone might still make about the novel lacking a proper ending plot-wise, it makes perfect sense emotionally. In close contention, though, is Gately’s first chapter, about the disastrous burglary in a “wildly upscale part of Brookline” that turns his life around. It’s the first section in the story really that took my breath away—that or I was holding my breath waiting in vain for a paragraph break to exhale. Anyway, the unsurprising answer regarding my favorite character is Don Gately. He’s maybe DFW’s single greatest creation.

Biblioklept: I agree with you on Gately being Wallace’s greatest achievement—I love the sections you mention as well. I think many people who can’t get into IJ probably don’t get to that burglary/toothbrush episode quick enough.

WB: I don’t know, the number of people who have made it to halfway or further and then still give up, just speaking anecdotally, is staggering. I’ve personally given up on much shorter books, which is probably every book I’ve given up on, considering I haven’t bothered to try Imperial or some of Vollmann’s other longer stuff. Plus, it’s not like there isn’t grabby material early on: the “where was the woman who said she’d come” scene with Erdedy is very dense, but I think immediately rewarding in a way some of the Hal and Orin material up front is not. And there’s no way around the fact it’s just a months-long project in a way few novels are.

Biblioklept: Have you had any response from Wallace’s estate about your project?

WB: I haven’t, nor have I solicited any. In development on the project, I had considered reaching out to Bonnie Nadell, but I didn’t really know what I’d be asking. This wasn’t going to be the first infographic project or fan art based on the book, so I didn’t think permission was an issue. A friend had offered to put me in contact with D.T. Max, if I needed, but I didn’t want to bother him, either. The most response I’ve had is two retweets and one reblog from whomever’s running social media for Little, Brown, and it’s more than I would have asked for.

Biblioklept: Do you have another project on the horizon after this one?

WB: To be honest, I’m not even sure I’m totally done with Infinite Jest yet. I’m still writing Infinite Boston on a daily basis through the end of this month, and we’re actually putting in some further refinements on the Infinite Atlas website. Besides that, I’d been editing a very short film when I turned to focus on this, so I’d like to complete that now. And I’m sure this isn’t my last map, either.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

WB: Haha, that’s a great question. And the answer is yes. One that comes to mind in particular I found in a teacher’s lounge in the j-school at the University of Oregon, where I worked and never quite completed my journalism double major. And I don’t have it handy—I’m afraid I’ve left stolen property on a shelf at my parents’ house—but it was called something like The Declining American Newspaper and its publication date could have been no later than 1965. Even when I found it, this was still early days of the Internet. I wasn’t sure whether it was prophetic or preposterous, which is basically why I pocketed it. Less a book, more a conversation piece. Next visit, I’ll try to make partial amends by actually reading it.

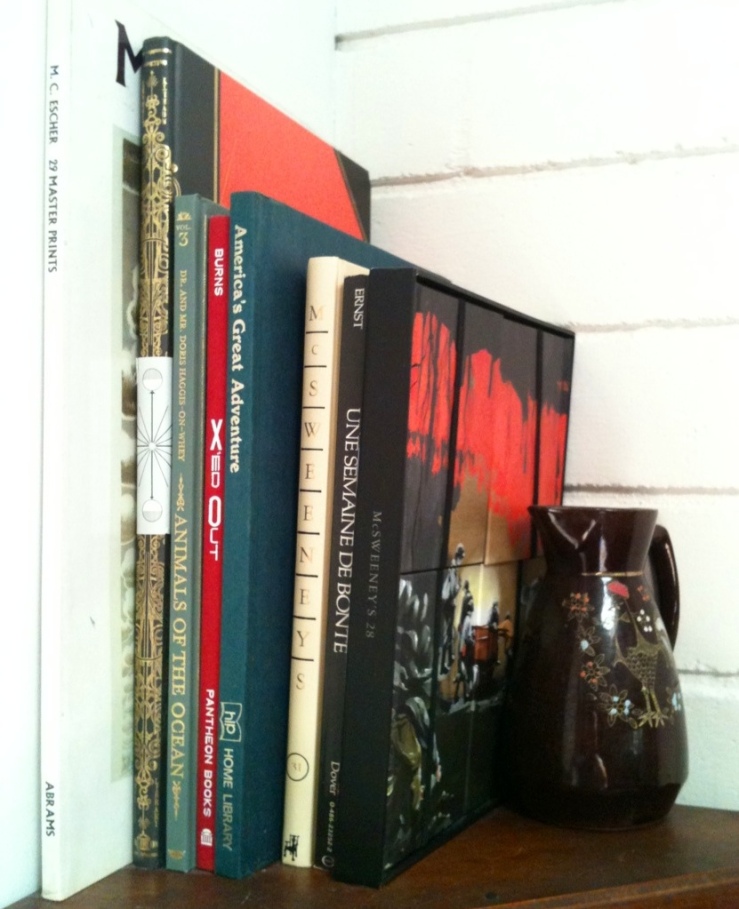

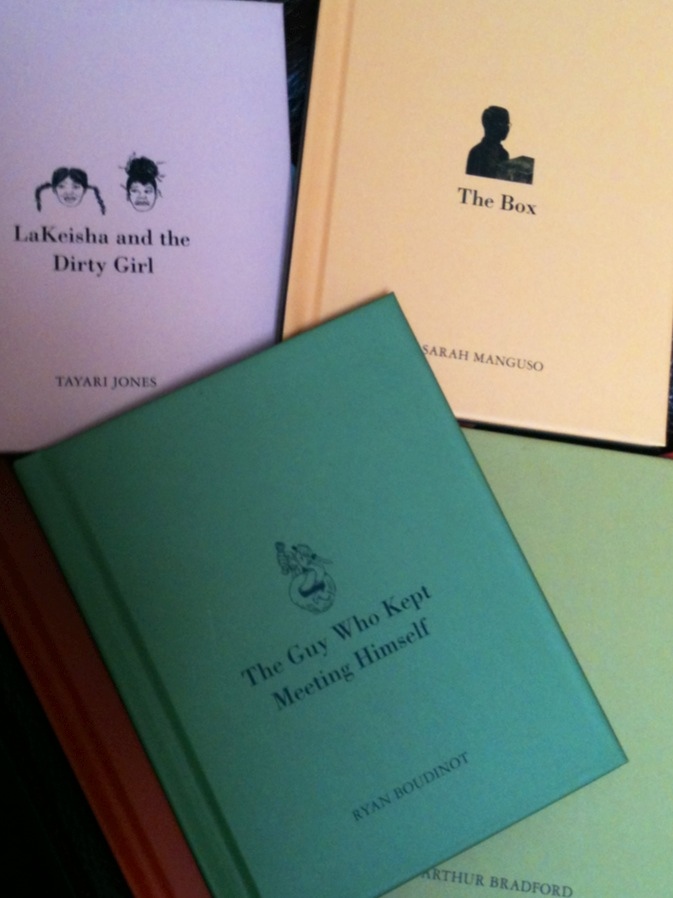

Book shelves series #38, thirty-eighth Sunday of 2012

The final entry on this corner piece.

What have these volumes in common? They are all aesthetically pleasing.

They are all too tall to fit elsewhere comfortably.

Several issues of McSweeney’s, some art books, and some graphic novels:

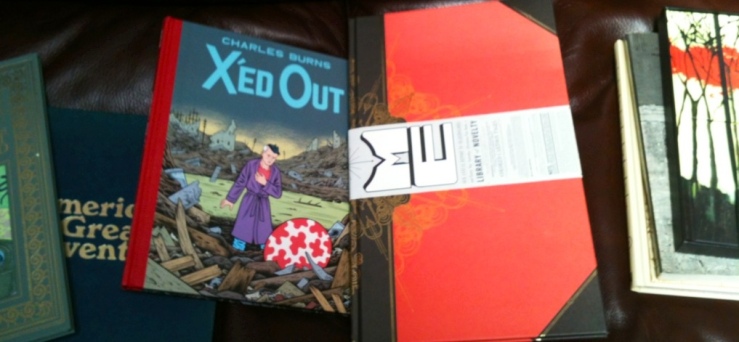

I’ve already expressed my strong enthusiasm for Charles Burns’s X’ed Out. The Acme Library pictured is part of Chris Ware’s series, and is beautiful and claustrophobic.

McSweeney’s #28 comprises eight little hardbacked fables that arrange into two “puzzle” covers:

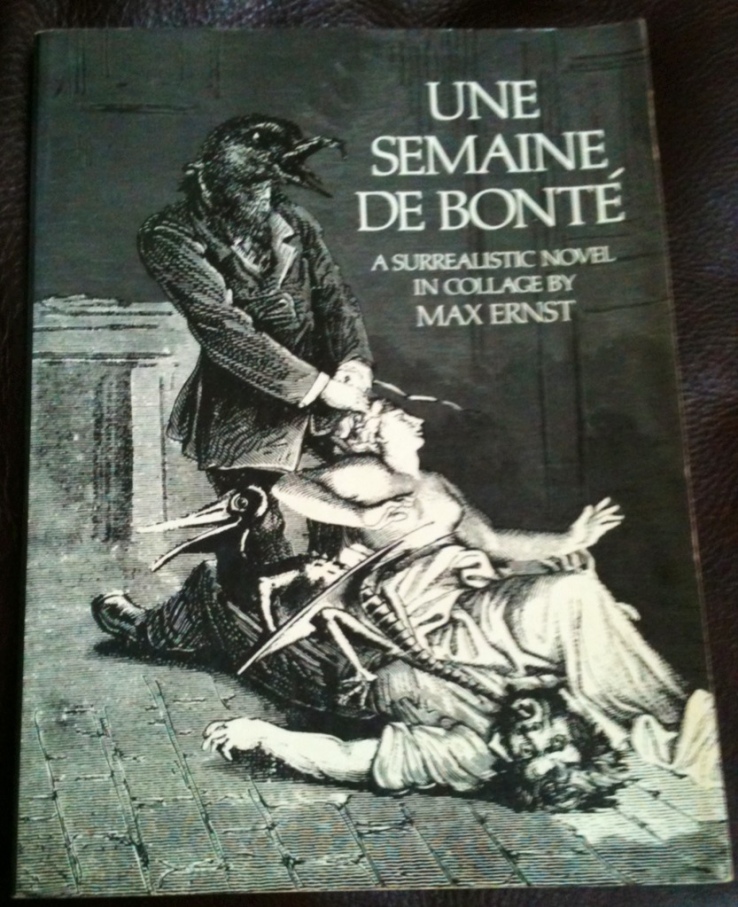

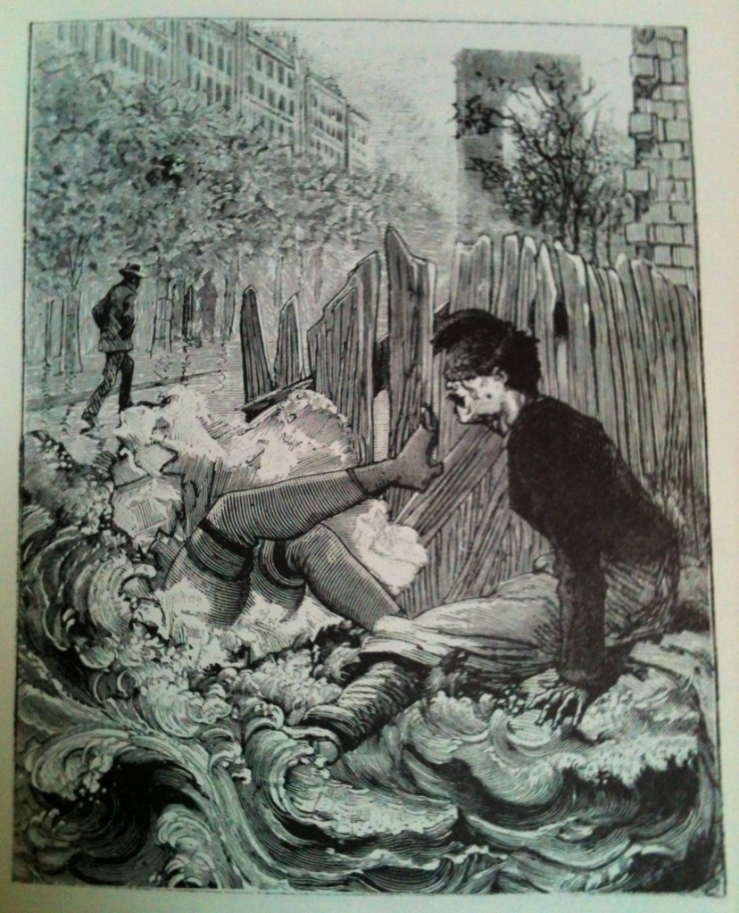

I’ve also written enthusiastically about Max Ernst’s surreal graphic novel, Une Semaine de Bonte:

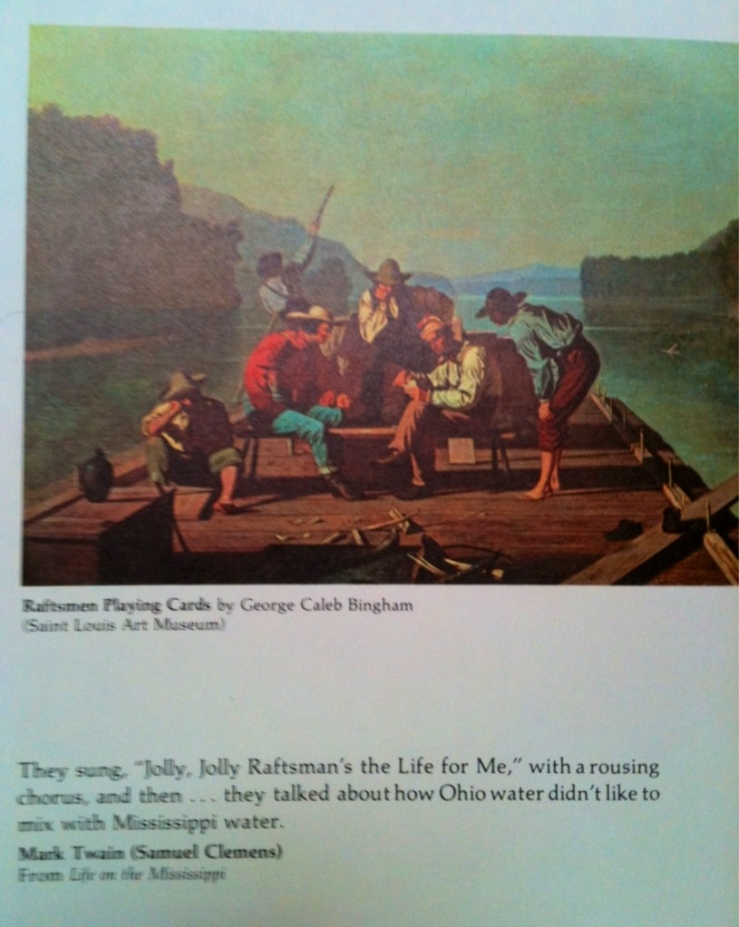

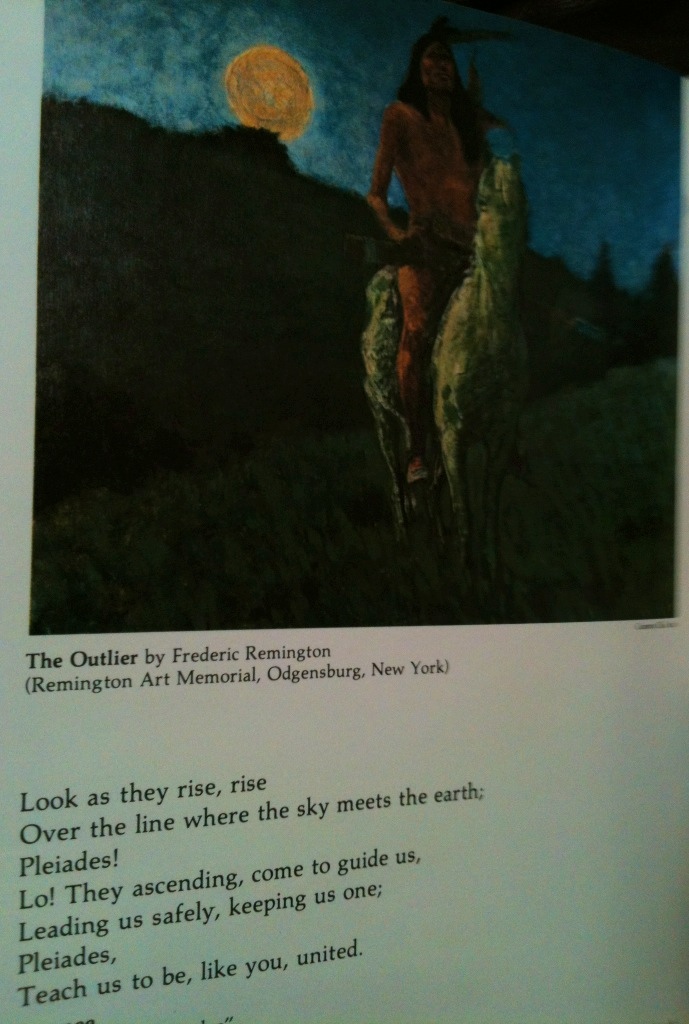

America’s Great Adventure is this wonderful book that pairs American writing (poems, songs, excerpts from novels and journals) with American paintings to tell a version of American history:

It probably deserves its own review. Short review: It’s a wonderful book if you can find it.

Our Eruptions.

Numberless things which humanity acquired in its earlier stages, but so weakly and embryonically that it could not be noticed that they were acquired, are thrust suddenly into light long afterwards, perhaps after the lapse of centuries: they have in the interval become strong and mature.

In some ages this or that talent, this or that virtue seems to be entirely lacking, as it is in some men; but let us wait only for the grandchildren and grandchildren s children, if we have time to wait, they bring the interior of their grandfathers into the sun, that interior of which the grandfathers themselves were unconscious. Often, the son already betrays the father and the father understands himself better after he has a son. We have all hidden gardens and plantations in us; and by another simile, we are all growing volcanoes, which will have their hours of eruption: how near or how distant this is, nobody of course knows, not even the good God.

—Fragment nine of The Gay Science by Friedrich Nietzsche.

John Hawkes and Javier Marías. Was looking for something else, spotted the ND spine (Hawkes) and The Believer Books aesthetic (Marías).

From the back of the Hawkes:

No synopsis conveys the quality of this now famous novel about an hallucinated Germany in collapse after World War II. John Hawkes, in his search for a means to transcend outworn modes of fictional realism, has discovered a highly original technique for objectifying the perennial degradation of mankind within a context of fantasy… Nowhere has the nightmare of human terror and the deracinated sensibility been more concisely analyzed than in The Cannibal. Yet one is aware throughout that such analysis proceeds only in terms of a resolutely committed humanism. (Hayden Carruth)

Here’s a description, sort of, of a 2006 review of Voyage Along the Horizon (from the NYT):

To judge the Spanish novelist and essayist Javier Marías solely on the basis of “Voyage Along the Horizon” would be akin to imagining Flaubert only from “Salammbô” or Nabokov from “Transparent Things.” Though these works aren’t insignificant in their own right, to read them without recourse to their authors’ larger bodies of work is to comprehend a complex organism only from its vestigial limbs.

Here is a picture of a colorful moth doing something to a basil plant in my back yard: