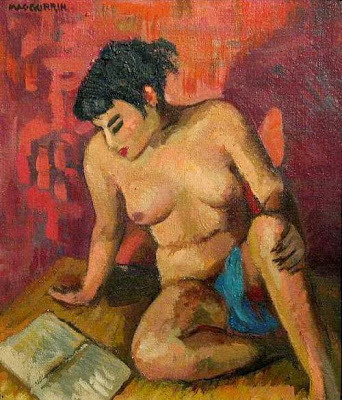

There are a number of difficulties with dirty words, the first of which is that there aren’t nearly enough of them; the second is that the people who use them are normally numskulls and prudes; the third is that in general they’re not at all sexy, and the main reason for this is that no one loves them enough. Contrary to those romantic myths which glorify the speech of mountain men and working people, Irish elves and Phoenician sailors, the words which in our language are worst off are the ones which the worst-off use. Poverty and isolation produce impoverished and isolated minds, small vocabularies, a real but fickle passion for slang, most of which is like the stuff which Woolworths sells for ashtrays, words swung at random, wildly, as though one were clubbing rats, or words misused in an honest but hopeless attempt to make do, like attacking tins with toothpicks; there is a dominance of cliché and verbal stereotype, an abundance of expletives and stammer words: you know, man, like wow! neat, fabulous, far-out, sensaysh. I am firmly of the opinion that people who can’t speak have nothing to say. It’s one more thing we do to the poor, the deprived: cut out their tongues . . . allow them a language as lousy as their lives.

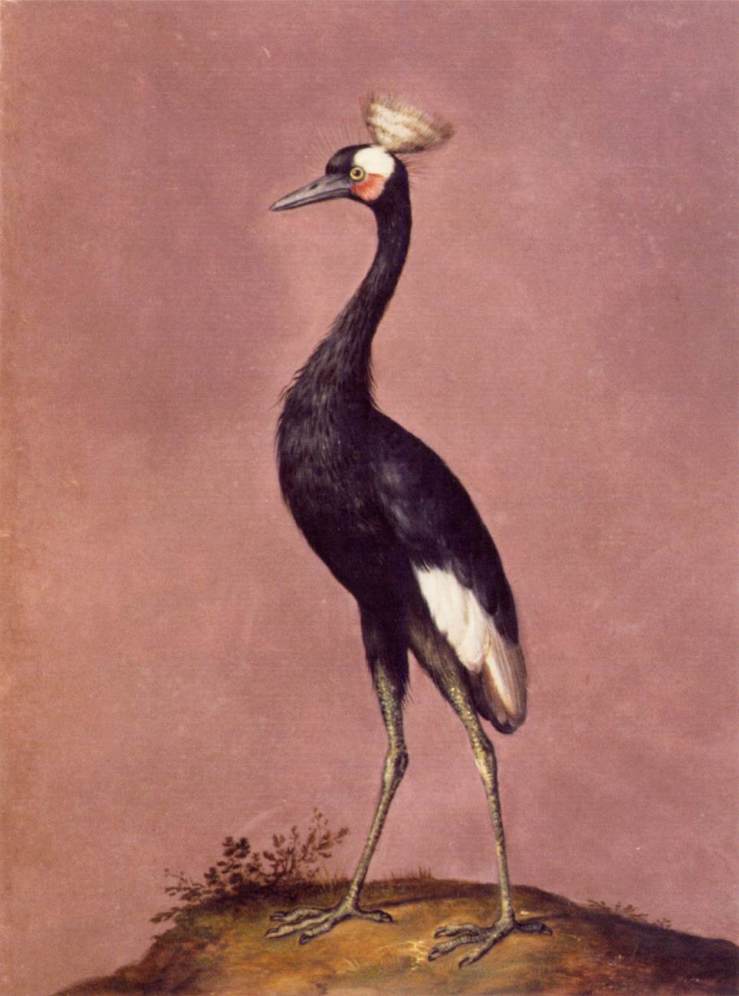

Thin in content, few in number, constantly abused: what chance do the unspeakables have? Change is resisted fiercely, additions are denied. I have introduced ‘squeer,’ ‘crott,’ ‘kotswinkling,’ and ‘papdapper,’ with no success. Sometimes obvious substitutes, like ‘socksucker,’ catch on, but not for long. What we need, of course, is a language which will allow us to distinguish the normal or routine fuck from the glorious, the rare, or the lousy one—a fack from a fick, a fick from a fock—but we have more names for parts of horses than we have for kinds of kisses, and our earthy words are all . . . well . . . ‘dirty.’ It says something dirty about us, no doubt, because in a society which had a mind for the body and other similarly vital things, there would be a word for coming down, or going up, words for nibbles on the bias, earlobe loving, and every variety of tongue track. After all, how many kinds of birds do we distinguish?

We have a name for the Second Coming but none for a second coming. In fact our entire vocabulary for states of consciousness is critically impoverished.

From William H. Gass’s On Being Blue.