I can’t remember which particular Surrealist I was googling when I learned about Gisèle Prassinos. I do know that it was just a few weeks ago, and I’ve had an interest in Surrealist art and literature since I was a kid, so I was a bit stunned that I’d never heard of her before now—strange, given the origin of her first publication. In 1934, when she was 14, Prassinos was “discovered” by André Breton, and the Surrealists delighted in what they called her “automatic writing.” (Prassinos would later reject that label, and go as far as to declare that she had never been a surrealist). Her first book, La Sauterelle arthritique (The Arthritic Grasshopper) was published just a year later.

I somehow found a .pdf of one of her stories, “A Nice Family,” a bizarre little tale that runs on its own surreal mythology. The story struck me as simultaneously grandiose and miniature, dense but also skeletal. It was impossible. Surreal. I wanted more.

Luckily, just this spring Wakefield Press released The Arthritic Grasshopper: Collected Stories, 1934-1944, a new English translation of a 1976 compendium of Prassinos’s tales, Trouver sans checher. The translation is by Henry Vale and Bonnie Ruberg, whose introduction to the volume is a better review and overview than I can muster here. Ruberg offers a miniature biography, and shares details from her letters and visits with Prassinos. She situates Prassinos within the Surrealists’ gender biases: “For a young writer such as Prassinos, being involved with the surrealists would have meant gaining access to resources like publishers, but it also would have meant being fetishized and marginalized.” Ruberg characterizes Prassinos’s tales eloquently and accurately—no simple feat given the material’s utter strangeness:

Taken collectively, their effect is a piercing cackle, a complete disorientation, rather than an ethical lesson. The politics of these stories are absurdist. They upend the world by making children dangerous, by reanimating the dead, by letting the carefully tended domestic deform, foam, and melt. No social structure holds power in the world of these stories—not on the basis of gender, or nationality, or class. The force that reigns is chaos.

Let’s look at that reigning chaos.

In “The Sensitivity of Others,” one of the earliest tales in the volume, we get the sparest narrative action seemingly possible: A speaker walks forward. And yet dream-nightmare touches impinge on all sides and on all senses. The opening line shows a world that is never stable, and if monsters and other dangers lurk just on the margins of our narrator’s shifting path, so do wonders and the promise of strange knowledge. Here’s the tale in full:

I still have no idea what to make of the punchline there at the end, but those final images—a father, a faulty library, a power failure—hang heavy against the narrator’s trembling walk.

Many of Prassinos’s anti-fables conclude with such apparent non sequiturs, and yet the final lines can also cast a weird light back over the previous sentences. In “Photogenic Quality,” a dream-tale about the act of writing itself, the final line at first appears as sheer absurdity. A man receives a pencil from a child, whittles it into powder, blots the powder on paper, and throws the paper in the river (more things happen, too). The tale concludes with the man declaring, “Brass is made from copper and tin.” It’s possible to enjoy the absurdity here on its own; however, I think we can also read the last line as a kind of Abracadabra!, magic words that describe an almost alchemical synthesis—a synthesis much like the absurd modes of transformative writing that “Photogenic Quality” outlines.

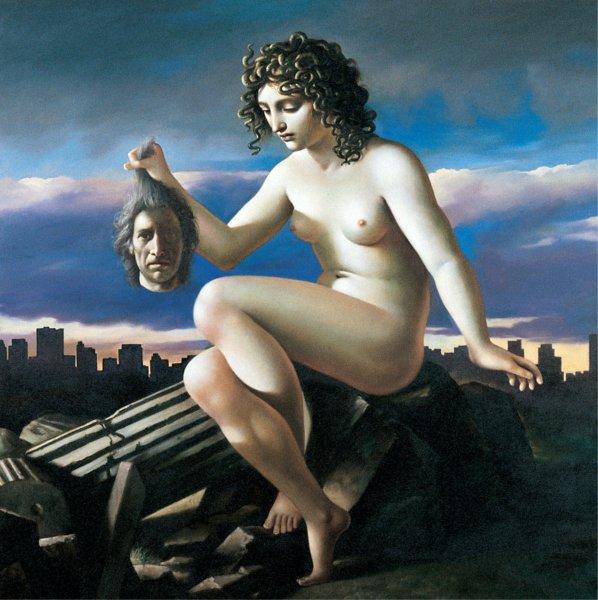

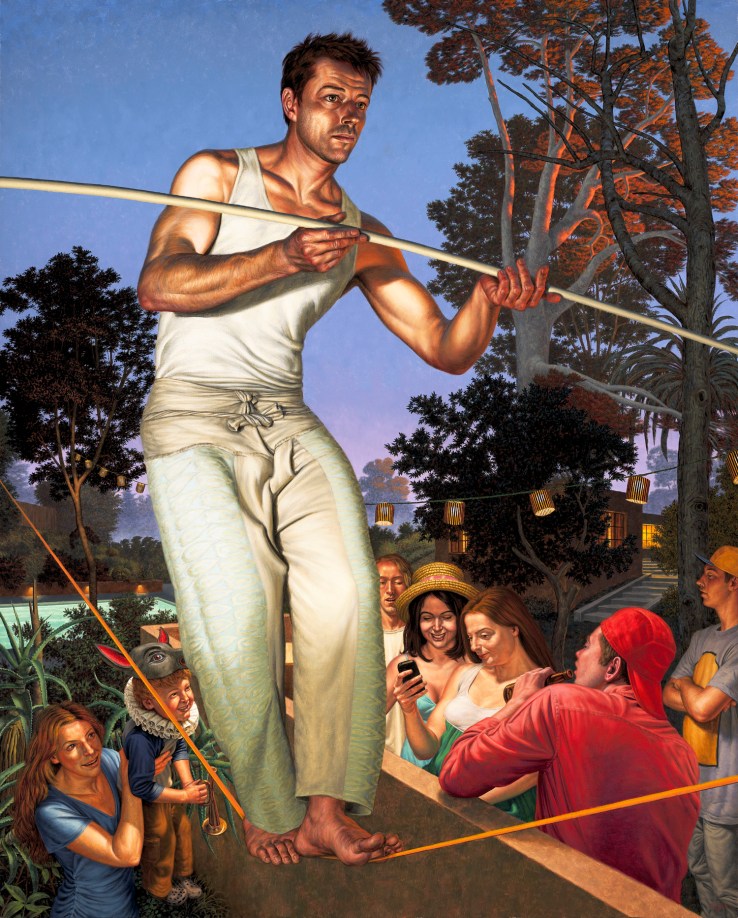

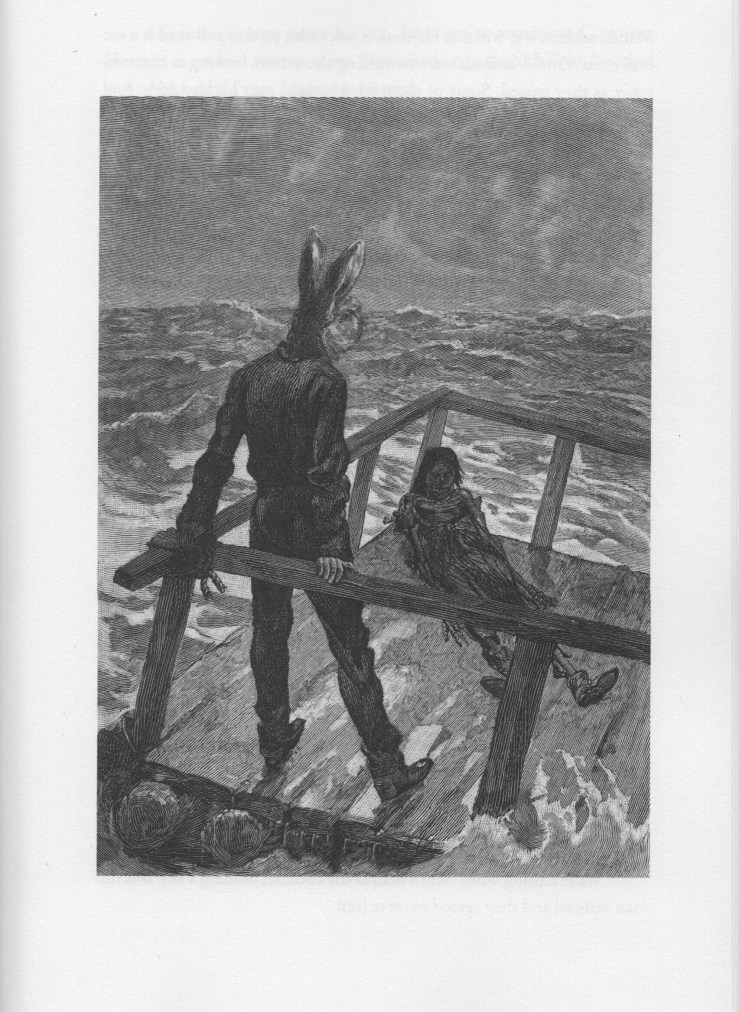

You’ll see above one of Allan Kausch’s illustrations for The Arthritic Grasshopper. Kausch’s collages pointedly recall Max Ernst’s surreal 1934 graphic novel Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness). Kausch’s work walks a weird line between horror and whimsy; images from old children’s books and magazines become chimerical figures, sometimes cute, sometimes horrific, and sometimes both. They’re lovely.

Surreal figures shift throughout the book—monks and kings, daughters and mothers, deep sea divers and knights and salesmen and talking horses—all slightly out of place, or, rather, all making new places. Even when Prassinos establishes a traditional space we might think we recognize—often a fairy trope—she warps its contours, shaping it into something else. “A Marriage Proposal,” with its unsuspecting title, opens with “Once upon a time” — but we are soon dwelling in impossibility: “the garter snake appeared in the doorway, arm in arm with the snail, who was slobbering with happiness.” Other stories, like “Tragic Fanaticism,” immediately condense fairy tales into pure images, leaving the reader to suss out connections. Here is that story’s opening line: “A black hole, a little old woman, animals.” At five pages, “Tragic Fanaticism” is one of the collection’s longer stories. It ends with a four line poem, sung by five red cats to the old woman: “Go home and burn / Darling / You’re the only one we’ll love / Trash Bin.”

I still have a number of stories to read in The Arthritic Grasshopper. I’ve enjoyed its tales most when taken as intermezzos between sterner (or compulsory) reading. There’s something refreshing in Prassinos’s illogic. In longer stretches, I find that I tire, get lazy—Prassinos’s imagery shifts quickly—there’s something even picaresque to the stories—and keeping up with its veering rhythms for tale after tale can be taxing. Better not to gobble it all up at once. In this sense, The Arthritic Grasshopper reminds me strongly of another recently-published volume of surreal, imagistic stories that I’ve been slowly consuming this year: The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. In their finest moments, both of these writers can offer new ways of looking at art, at narrative, at the world itself.

I described Prassinos’s tales as “anti-fables” above—a description that I think is accurate enough, as literary descriptions go—but that doesn’t mean there isn’t something that we can learn from them (although, to be very clear, I do not think literature has to offer us anything to learn). What Prassinos’s anti-fables do best is open up strange impossible spaces—there’s a kind of radical, amorphous openness here, one that might be neatly expressed in the original title to this newly-translated volume—Trouver sans checher—To Find without Seeking.

In her preface (titled “To Find without Seeking”) Prassinos begins with the question, “To find what?” Here is a question that many of us have been taught we must direct to all the literature we read—to interrogate it so that it yields moral instruction. Prassinos answers: “The spot where innocence rejoices, trembling as it first meets fear. The spot where innocence unleashes its ferocity and its monsters.” She goes on to describe a “true and complete world” where the “earth and water have no borders and each us can live there if we choose, in just the same way, without changing our names.” Her preface concludes by repeating “To find what?”, and then answering the question in the most perfectly (im)possible way: “In the end, the mind that doesn’t know what it knows: the free astonishing voice that speaks, faceless, in the night.” Prassinos’s anti-fables offer ways of reading a mind that doesn’t know what it knows, of singing along with the free faceless astonishing voice. Highly recommended.