“Fans”

by

Barry Hannah

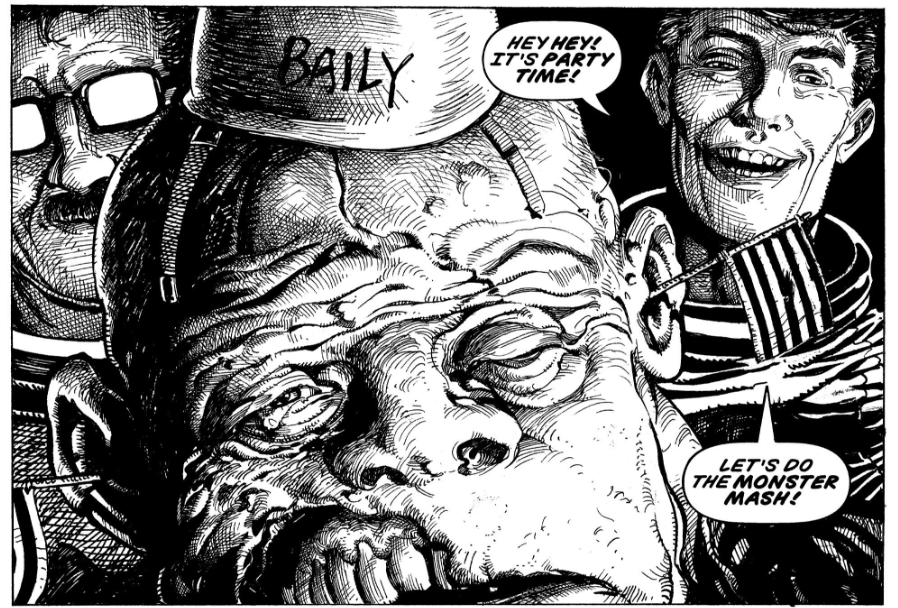

Wright’s father, a sportswriter and a hack and a shill for the university team, was sitting next to Milton, who was actually blind but nevertheless a rabid fan, and Loomis Orange, the dwarf who was one of the team’s managers. The bar was out of their brand of beer, and they were a little drunk, though they had come to that hard place together where there seemed nothing, absolutely nothing to say.

The waitress was young. Normally, they would have commented on her and gone on to pursue the topic of women, the perils of booze, or the like. But not now. Of course it was the morning of the big game in Oxford, Mississippi.

Someone opened the door of the bar, and you could see the bright wonderful football morning pouring in with the green trees, the Greek-front buildings, and the yelling frat boys. Wright’s father and Loomis Orange looked up and saw the morning. Loomis Orange smiled, as did Milton, hearing the shouts of the college men. The father did not smile. His son had come in the door, swaying and rolling, with one hand to his chest and his walking stick in the other.

Wright’s father turned to Loomis and said, “Loomis, you are an ugly distorted little toad.”

Loomis dropped his glass of beer.

“What?” the dwarf said.

“I said that you are ugly,” Wright said.

“How could you have said that?” Milton broke in.

Wright’s father said, “Aw, shut up, Milton. You’re just as ugly as he is.”

“What’ve I ever did to you?” cried Milton.

Wright’s father said, “Leave me alone! I’m a writer.”

“You ain’t any kind of writer. You an alcoholic. And your wife is ugly. She’s so skinny she almost ain’t even there!” shouted the dwarf.

People in the bar—seven or eight—looked over as the three men spread, preparing to fight. Wright hesitated at a far table, not comprehending.

His father was standing up.

“Don’t, don’t, don’t,” Wright said. He swayed over toward their table, hitting the floor with his stick, moving tables aside.

The waitress shouted over, “I’m calling the cops!”

Wright pleaded with her: “Don’t, don’t, don’t!”

“Now, please, sit down everybody!” somebody said.

They sat down. Wright’s father looked with hatred at Loomis. Milton was trembling. Wright made his way slowly over to them. The small bar crowd settled back to their drinks and conversation on the weather, the game, traffic, etc. Many of the people talked about J. Edward Toole, whom all of them called simply Jet. The name went with him. He was in the Ole Miss defensive secondary, a handsome figure who was everywhere on the field, the star of the team. Continue reading ““Fans” — Barry Hannah” →