My James M. Cain discovery tour continued with Double Indemnity, which I loved loved loved. The novel’s terse, mean, a bit queasy, and zippy as hell. Over the July 4th weekend my uncle and I made plans to watch Billy Wilder’s 1944 film adaptation, but maybe heat and alcohol got in the way. I’ll get to it soon. (I stalled out in Mildred Pierce, although I did see that film—the 1945 one with Joan Crawford.)

I checked out Roberto Bolaño’s “newest” collection of novellas, Cowboy Graves, from the library. I’ll probably pick it up in paperback or used when I get the chance. It’s a fragmentary affair, and paradoxically seems more complete because of this. Other “unfinished” pieces like Woes of the True Policeman and The Spirit of Science Fiction felt like dress rehearsals to his big boys—The Savage Detectives and 2666—but the trio in Cowboy Graves fit neatly if weirdly into the Bolañoverse proper. Good stuff.

I tore through four novels by British wrtier B.S. Johnson earlier this year before taking up his most gimmicky work— his “book in a box,” 1969’s The Unfortunates. The book consists of 27 pamphlets. One is labeled “FIRST”, another “LAST,” but it’s up to the reader to shuffle and go for it. I think there is a reason most novels are not composed in this format. If you are intrested in Johnson, check out Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry or Albert Angelo.

I will give Evan Dara’s new novel Permanent Earthquake a proper review when I finish it. I will simply state here that finishing it has been a slog. This may be a rhetorical conceit–the novel is about a world, or an island, which I suppose is its own world, in a state of permanent earthquake—or really the novel is about one dude in this world island of permanent earthquakes, trying to find a still spot. It’s clearly an allegory of late capitalist whatever butting up against climate disaster, and it’s very depressing, and it’s a slog slog slog. I think Dara is an important contemporary writer and I will do a better job assessing Permanent Earthquake when I finish it.

I picked up a used copy of Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics a couple of weeks ago, largely because of its lovely cover. I’d read the book years ago, and mostly remember being amused and frustrated by it. Shelving it, I pulled out a trio of Calvino’s I hadn’t read in ages: Invisible Cities, If on a winter’s night a traveler, and The Baron in the Trees.

I started in on Invisible Cities (trans. William Weaver); I first read it on a train from Bangkok to Chiang Mai twenty years ago. My friend loaned it to me. He spent the night drinking with Germans; I read Calvino’s prose-poem-essay-cyle-thing over a few hours. Rereading it I found so much more—more humor, more humanity, more life. As a young man I think I demanded its philosophy, its semiotics, its brains. There’s more heart there than I remembered.

I then took up If on a winter’s night a traveler (trans William Weaver). I realized that I’d never read the novel just to read it—I read it as an undergrad and then as a grad student, and both times, like a character in the novel, I read it looking for bits of evidence to support an idea I already had. Winter’s night is a bit too long; its metatextual postmodernism starts to wear thin—you can almost open the novel at random to find it describing itself—but it is probably the best postmodernist example of a novel about reading a novel I can think of. (It’s also hornier than I remember.)

And so well now I’m in the middle of Calvino’s much-earlier novel, The Baron in the Trees (trans. Archibald Colquhoun). The story of a rebellious young aristocrat who vows to live in the trees and never set foot on ground again, Baron burns with a focused narrative heat absent in Calvino’s later more self-consciously postmodern work. It’s not exactly a picaresque, but it’s still one damn thing happening after another, and I love it.

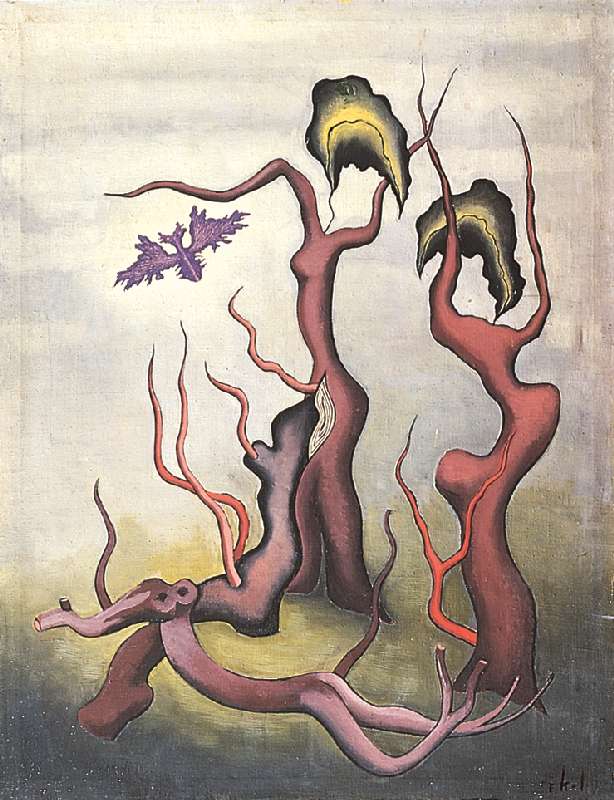

Entanglement, 2016 by

Entanglement, 2016 by