From “A MAD Look at Alfred Hitchcock Movies” by Sergio Aragones, MAD Magazine #10, Dec. 2019.

From “A MAD Look at Alfred Hitchcock Movies” by Sergio Aragones, MAD Magazine #10, Dec. 2019.

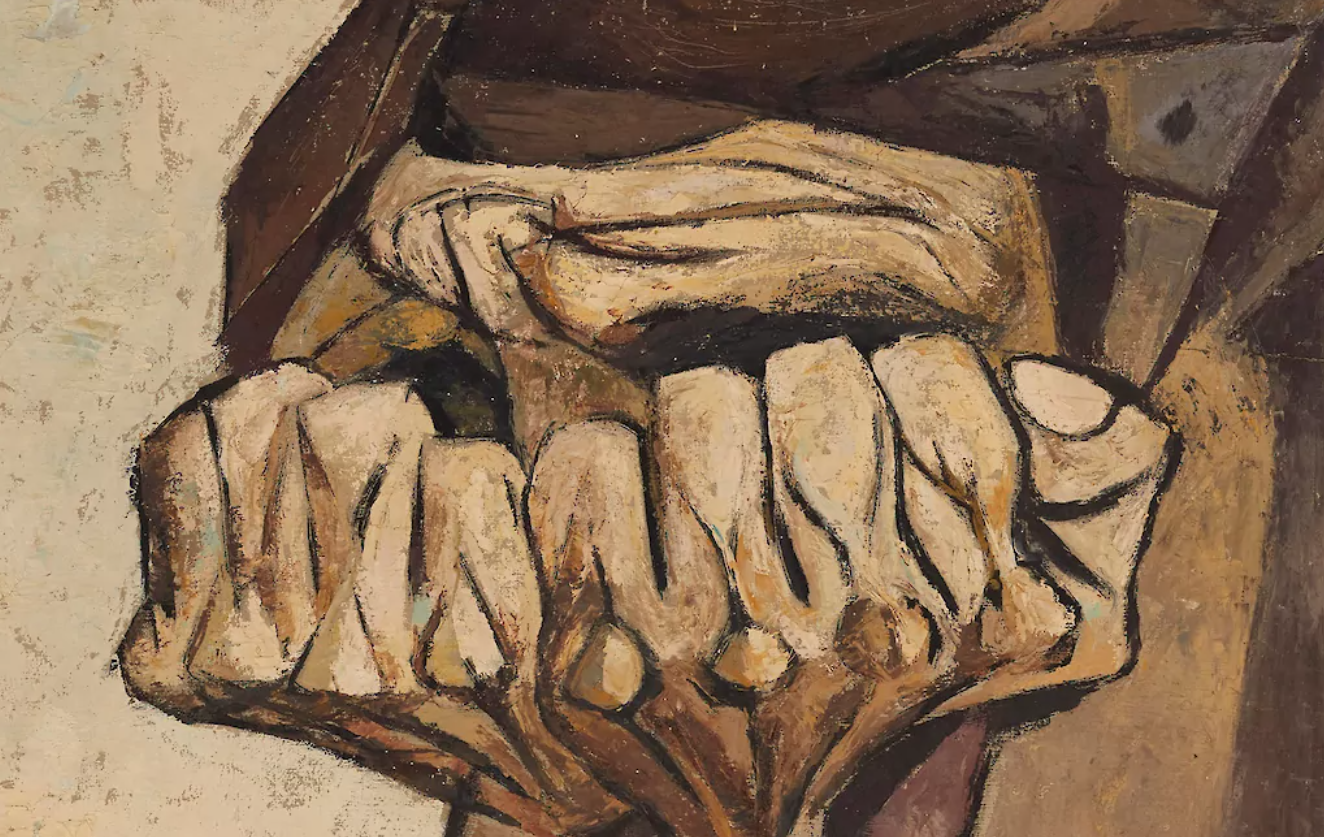

Untitled (Detail), 1964 by Eduardo Kingman (1913-1997)

I don’t want to write what I’m writing, but if I don’t write it I don’t think I will be able to write anything here again. I am not going to work on the thing that I am writing right now, I’m just going to write it and let it be messy and incomplete, riddled with absences, mistakes, oversights, smaller and larger failures, possible and probable grammatical and mechanical errors — but no erasures.

On Monday, this Monday, two days ago, my closest friend, my best friend of over three decades, died unexpectedly in his sleep. He went to sleep and did not wake up. He was there and then he wasn’t, or his consciousness wasn’t there, or isn’t here, or isn’t here in a form I can communicate with, that I know of. I feel as if something unnameable has been ripped out of my world. (He has a name, but the thing ripped out of the world is more than the name, more than the friendship, more than the years.) I have experienced grief before, for both friends and family, social grief and cultural grief and political grief and even parasocial grief. Nothing has ever hurt this intensely, and when the pain disappears it is replaced with hollow anxiety and muted dread.

I first met my friend when my family returned to the United States in 1991. It was during the final semester of the sixth grade. The city we moved to, where my parents had more or less grown up, was conducting a short, miserable experiment which was to put all of the city’s sixth graders into two schools. So, instead of having a junior high or middle school with its separate grades and hierarchies of time, tradition, seniority, whatever, I landed in an asylum crowded with hormonal mutants trying to establish dominance over each other in endless games of petty cruelty. I don’t remember my friend, who was not yet my friend of thirty years, being especially kind to me in any way that I understood as kindness. I do know that he talked to me like I was an actual person and not just a freak who was maybe not actually American. He let me borrow his Aerosmith tapes and copy them on my dad’s tape player. He had no interest in my R.E.M. CD. (I don’t think he had a CD player). Through the end of the sixth grade year we collaborated well together, working diligently in tandem to erode our citizenship grades from A’s to D’s.

We attended different middle schools (I think middle school was a new term, a transition from junior high). The next time I saw him was in ninth grade orientation. The moment of recognition remains one of the most wonderful feelings I’ve ever had: Here was my old friend; maybe he could be my new friend. By the end of ninth grade we were on our third rock band. We had finally found a real drummer. Actually he wasn’t a real drummer, but he was very good at playing the drums, a natural. He played on borrowed sets and we practiced on pieces we slowly put together through different forms of theft. This person, this drummer who wasn’t actually a drummer, he’s dead too now. But back to my friend.

My friend–we played music together forever. Bands in high school, college, after college. House parties, punk shows at the Elk’s Club or whatever the fuck it was, churches, all ages clubs, shitty night clubs, shitty rock clubs. We opened for the Moe Tucker Band and stole all their oranges and beers and drank them on the roof of the club (I never saw the Velvets legend perform; later she joined the Tea Party, I think). We opened for Limp Bizkit when they were still Limp Biscuit. Our drummer’s alcoholic mother was there with some guy who wasn’t his dad. She had no idea her son was there. We opened and played with dozens and dozens of local and touring bands that were so, so fucking good, and sometimes we were so fucking good too. We put out an album. We made endless four track recordings, as a band but also as a duo, also just swapping tapes. (We also swapped notebooks for two years — I want to say most of tenth and eleventh grade — where we worked on a “novel.” The “novel” was awful but it was so so so much fun to write. We would trade off chapters with no plotting in mind, changing the genre or direction of the tale, mostly just practicing, I guess. I guess I just liked reading what he wrote and maybe he liked reading what I wrote.) In college we played fewer shows out but recorded music more seriously. We made a Christmas album and gave CDs to our friends and family. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to listen to it again, although I’ve had my friend’s vocal on “Silver Bells” running through my head since Monday morning, the morning I was sitting here on the black leather couch I pretend is an office where I am sitting here right now on Wednesday morning, forty-eight hours after his wife called me with the awful awful news that my friend had died in his sleep.

I am ranting of course, and I would apologize, but this isn’t for any reader and this isn’t an elegy for my friend, this is for me. Maybe what I am trying to emphasize is that our friendship, our love for each other, was deeply wrapped up in creation, in art, in a lifelong discussion of music, art, film, literature. He encouraged me to start a blog. He told me he thought I’d be good at it. He was, I’m pretty sure, the only reader for this blog for the first few months.

He always gave me his honest opinion. When I was doing something that he thought was not good, he told me. If he thought I could do better, he told me. People use the term “partner in crime” as a cute way to describe their closest friend; we were actual partners in actual crimes. Most of the crimes were petty and none of them were violent. They were all stupid, and we learned from them, I think.

We traveled together, we were in each other’s weddings. We walked into adulthood, or whatever it is we are dealing with here, in different ways. I married at a younger age and had kids much younger than he did, which made him erroneously believe that I had some expertise in these matters. We were texting about his wife and his kids on the Sunday that he did not wake up from. We were texting about the finale of The Righteous Gemstones, which we were both looking forward to. (My wife was too tired to watch it that night–did my friend get to see the end? Is this the stupidest thought I’ve had over the past few days? Maybe because it’s one of the last things we were texting about. And the last thing he texted in our last conversation: how excited he was about the forthcoming Stereolab record. We were reminiscing about cruising around in his old jeep, the “Red Death,” as we called it, blasting Emperor Tomato Ketchup all summer, the summer before senior year. I am not a God I wish I could go do that one more time person, but now maybe I am, maybe like, God I wish I could cruise around just one more time like that with you person.) So well anyway, we were texted about Big things but also Small things, mundane stuff, day-to-day stuff. We texted every day, throughout the day. He only lived forty minutes from me, but we didn’t get to see each other as often as we’d like to (work, kids, life…). So we were in a state of constant written communication, passing ideas and jokes and observations back and forth, then bursting into the Big stuff, the new challenges of Growing Up.

I don’t think I ever really felt scared of any new frontier in my life because he was there with me in some way. I was never really alone. I had a partner. I had a true, great friend. And I think if you can have a true friend in your life that’s the greatest gift. But he’s gone somewhere ahead of me now, and he went way too fucking soon, and the gift he left behind is a New Feeling for me, a pain I cannot express or articulate but rather try to displace here in words, words, words that do nothing. I miss you Nick.

“Poem”

by

Langston Hughes

I loved my friend.

He went away from me.

There’s nothing more to say.

The poem ends,

Soft as it began,—

I loved my friend.

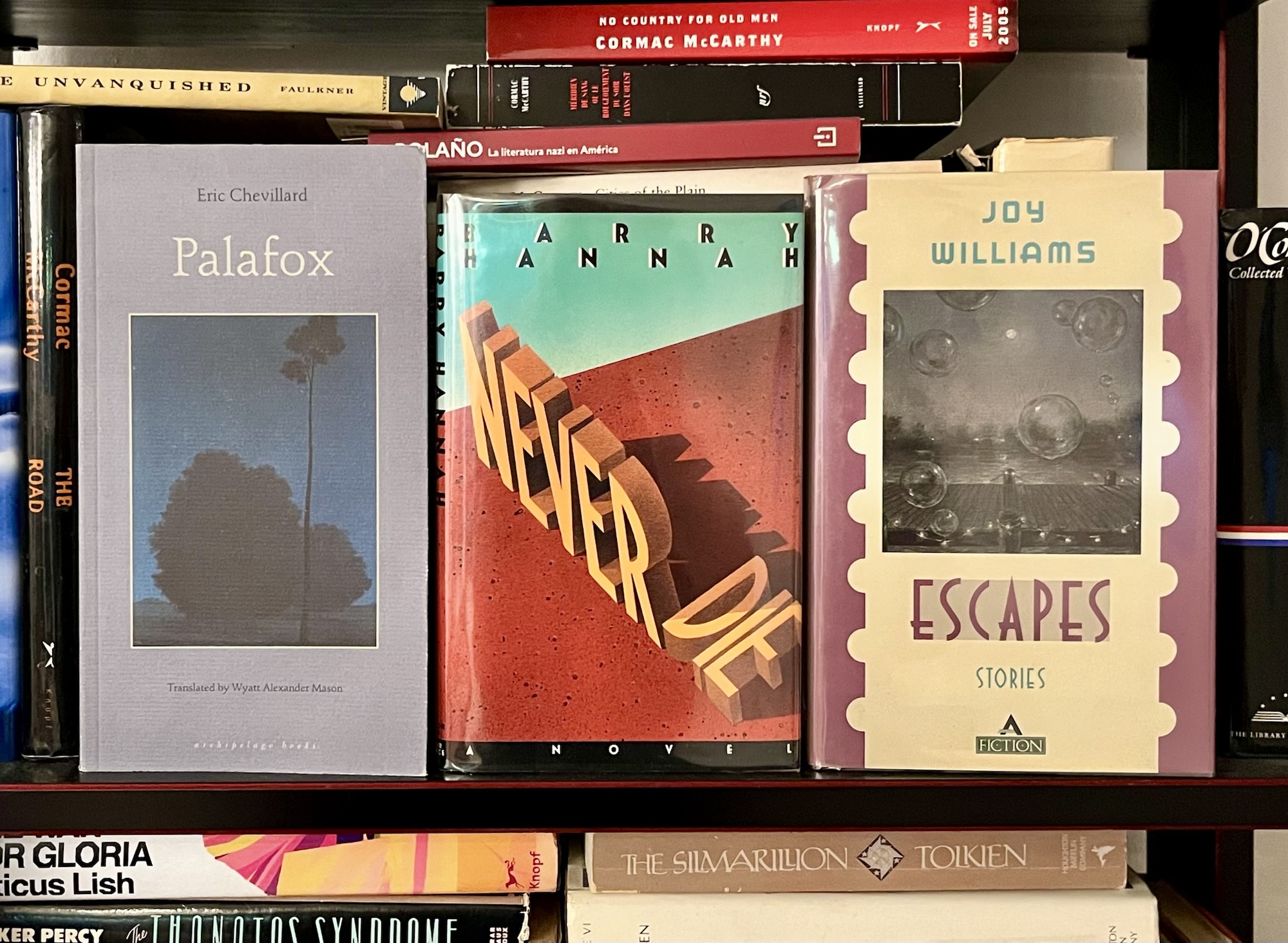

I dropped off a few books for trade credit and wound up with hardback first editions of Barry Hannah’s Never Die and Joy Williams’ 1990 collection Escapes. I also couldn’t pass up on Éric Chevillard’s Palafox in translation by Wyatt Mason. (I really dug Chris Clarke’s translation of Chevillard’s short novel The Posthumous Works of Thomas Pilaster.)

If you feel like feeling a little depressed and feeling a little amused in a way that creates a new, not-so-little feeling, you can read the title track of Joy Williams’ Escapes, “Escapes” (by Joy Williams) at Granta. From the story:

My mother was a drinker. Because my father left us, I assumed he was not a drinker, but this may not have been the case. My mother loved me and was always kind to me. We spent a great deal of time together, my mother and I. This was before I knew how to read. I suspected there was a trick to reading, but I did not know the trick. Written words were something between me and a place I could not go. My mother went back and forth to that place all the time, but couldn’t explain to me exactly what it was like there. I imagined it to be a different place.

As a very young child, my mother had seen the magician Houdini. Houdini had made an elephant disappear. He had also made an orange tree grow from a seed right on the stage. Bright oranges hung from the tree and he had picked them and thrown them out into the audience. People could eat the oranges or take them home, whatever they wanted.

How did he make the elephant disappear, I asked.

‘He disappeared in a puff of smoke,’ my mother said. ‘Houdini said that even the elephant didn’t know how it was done.’

Was it a baby elephant, I asked.

My mother sipped her drink. She said that Houdini was more than a magician, he was an escape artist. She said that he could escape from handcuffs and chains and ropes.

‘They put him in straitjackets and locked him in trunks and threw him in swimming pools and rivers and oceans and he escaped,’ my mother said. ‘He escaped from water-filled vaults. He escaped from coffins.’

I said that I wanted to see Houdini.

‘Oh, Houdini’s dead, Lizzie,’ my mother said. ‘He died a long time ago. A man punched him in the stomach three times and he died.’

Dead. I asked if he couldn’t get out of being dead.

‘He met his match there,’ my mother said.

From “Rude Interlude” by Robert E. Armstrong, Mickey Rat #4, 1982.

“The Nose”

by

Nikolai Gogol

translated by Claud Field

On the 25th March, 18—, a very strange occurrence took place in St Petersburg. On the Ascension Avenue there lived a barber of the name of Ivan Jakovlevitch. He had lost his family name, and on his sign-board, on which was depicted the head of a gentleman with one cheek soaped, the only inscription to be read was, “Blood-letting done here.”

On this particular morning he awoke pretty early. Becoming aware of the smell of fresh-baked bread, he sat up a little in bed, and saw his wife, who had a special partiality for coffee, in the act of taking some fresh-baked bread out of the oven.

“To-day, Prasskovna Ossipovna,” he said, “I do not want any coffee; I should like a fresh loaf with onions.”

“The blockhead may eat bread only as far as I am concerned,” said his wife to herself; “then I shall have a chance of getting some coffee.” And she threw a loaf on the table.

For the sake of propriety, Ivan Jakovlevitch drew a coat over his shirt, sat down at the table, shook out some salt for himself, prepared two onions, assumed a serious expression, and began to cut the bread. After he had cut the loaf in two halves, he looked, and to his great astonishment saw something whitish sticking in it. He carefully poked round it with his knife, and felt it with his finger.

“Quite firmly fixed!” he murmured in his beard. “What can it be?”

He put in his finger, and drew out—a nose!

Ivan Jakovlevitch at first let his hands fall from sheer astonishment; then he rubbed his eyes and began to feel it. A nose, an actual nose; and, moreover, it seemed to be the nose of an acquaintance! Alarm and terror were depicted in Ivan’s face; but these feelings were slight in comparison with the disgust which took possession of his wife.

“Whose nose have you cut off, you monster?” she screamed, her face red with anger. “You scoundrel! You tippler! I myself will report you to the police! Such a rascal! Many customers have told me that while you were shaving them, you held them so tight by the nose that they could hardly sit still.”

But Ivan Jakovlevitch was more dead than alive; he saw at once that this nose could belong to no other than to Kovaloff, a member of the Municipal Committee whom he shaved every Sunday and Wednesday.

“Stop, Prasskovna Ossipovna! I will wrap it in a piece of cloth and place it in the corner. There it may remain for the present; later on I will take it away.”

“No, not there! Shall I endure an amputated nose in my room? You understand nothing except how to strop a razor. You know nothing of the duties and obligations of a respectable man. You vagabond! You good-for-nothing! Am I to undertake all responsibility for you at the police-office? Ah, you soap-smearer! You blockhead! Take it away where you like, but don’t let it stay under my eyes!”

Ivan Jakovlevitch stood there flabbergasted. He thought and thought, and knew not what he thought.

“The devil knows how that happened!” he said at last, scratching his head behind his ear. “Whether I came home drunk last night or not, I really don’t know; but in all probability this is a quite extraordinary occurrence, for a loaf is something baked and a nose is something different. I don’t understand the matter at all.” And Ivan Jakovlevitch was silent. The thought that the police might find him in unlawful possession of a nose and arrest him, robbed him of all presence of mind. Already he began to have visions of a red collar with silver braid and of a sword—and he trembled all over.

At last he finished dressing himself, and to the accompaniment of the emphatic exhortations of his spouse, he wrapped up the nose in a cloth and issued into the street.

He intended to lose it somewhere—either at somebody’s door, or in a public square, or in a narrow alley; but just then, in order to complete his bad luck, he was met by an acquaintance, who showered inquiries upon him. “Hullo, Ivan Jakovlevitch! Whom are you going to shave so early in the morning?” etc., so that he could find no suitable opportunity to do what he wanted. Later on he did let the nose drop, but a sentry bore down upon him with his halberd, and said, “Look out! You have let something drop!” and Ivan Jakovlevitch was obliged to pick it up and put it in his pocket.

A feeling of despair began to take possession of him; all the more as the streets became more thronged and the merchants began to open their shops. At last he resolved to go to the Isaac Bridge, where perhaps he might succeed in throwing it into the Neva.

But my conscience is a little uneasy that I have not yet given any detailed information about Ivan Jakovlevitch, an estimable man in many ways.

Like every honest Russian tradesman, Ivan Jakovlevitch was a terrible drunkard, and although he shaved other people’s faces every day, his own was always unshaved. His coat (he never wore an overcoat) was quite mottled, i.e. it had been black, but become brownish-yellow; the collar was quite shiny, and instead of the three buttons, only the threads by which they had been fastened were to be seen. Continue reading ““The Nose,” an absurd tale by Nikolai Gogol”

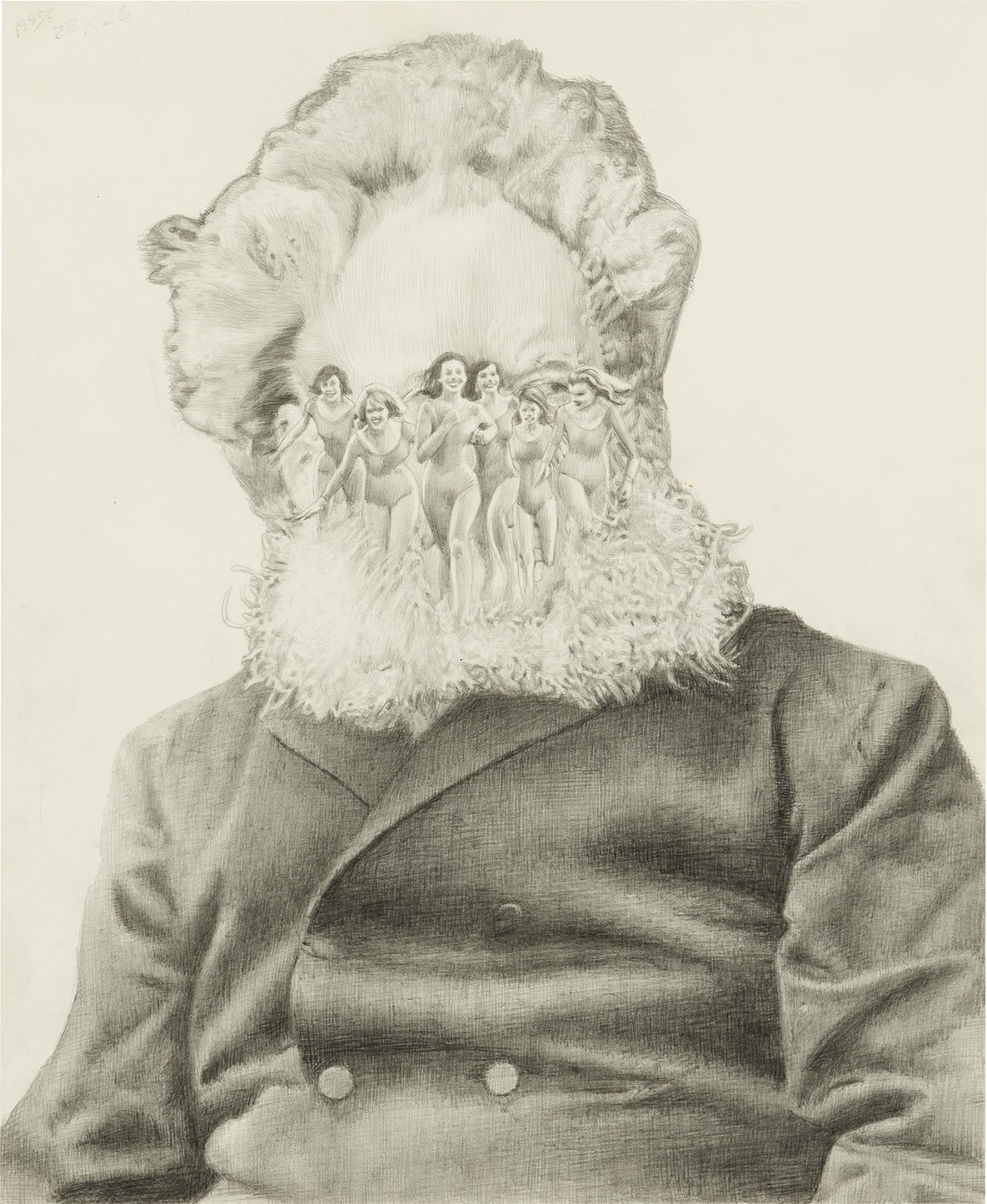

Couragemodell(a), 2022 by Giulia Andreani (b. 1985)

Couragemodell(a), 2022 by Giulia Andreani (b. 1985)

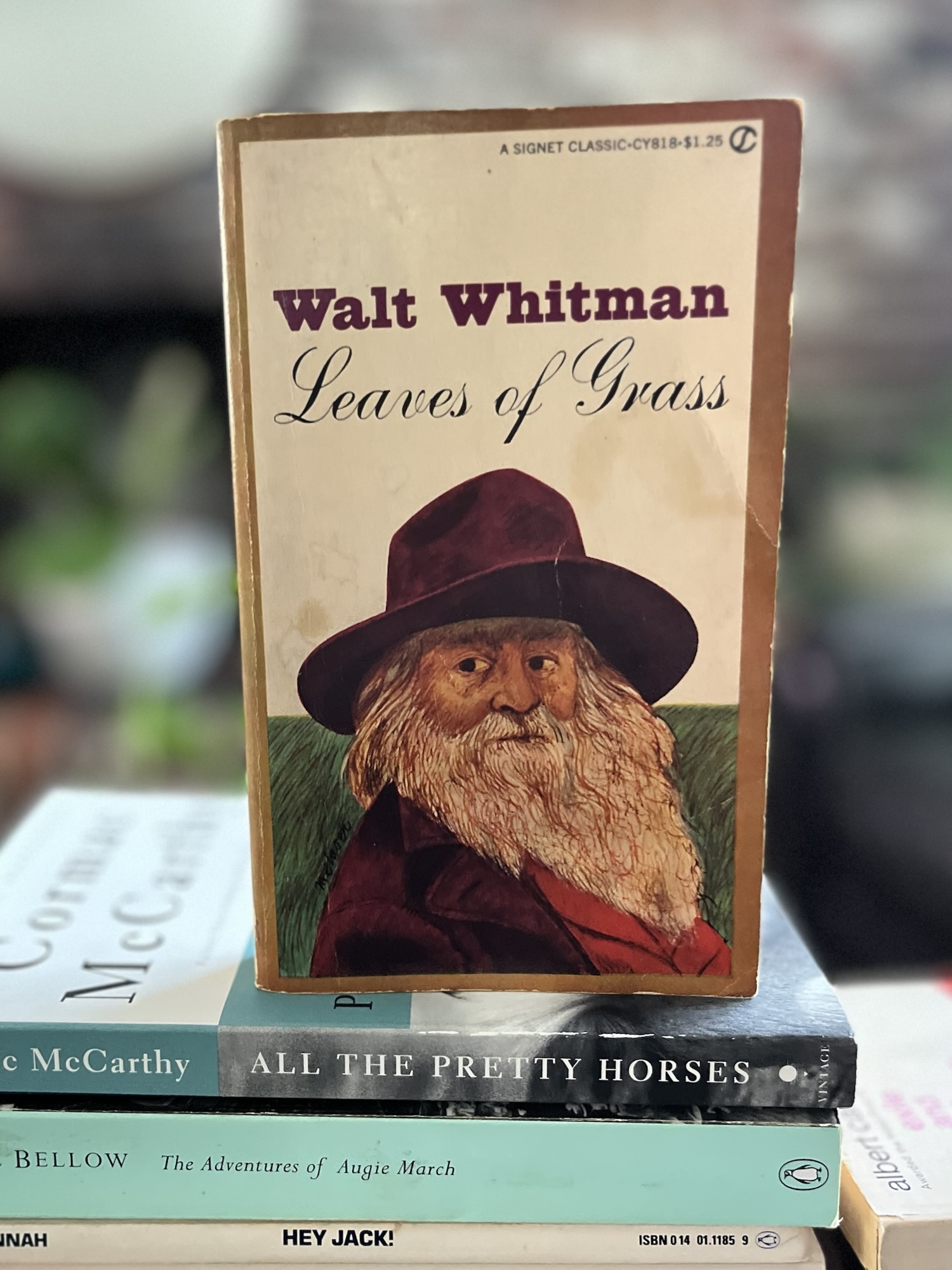

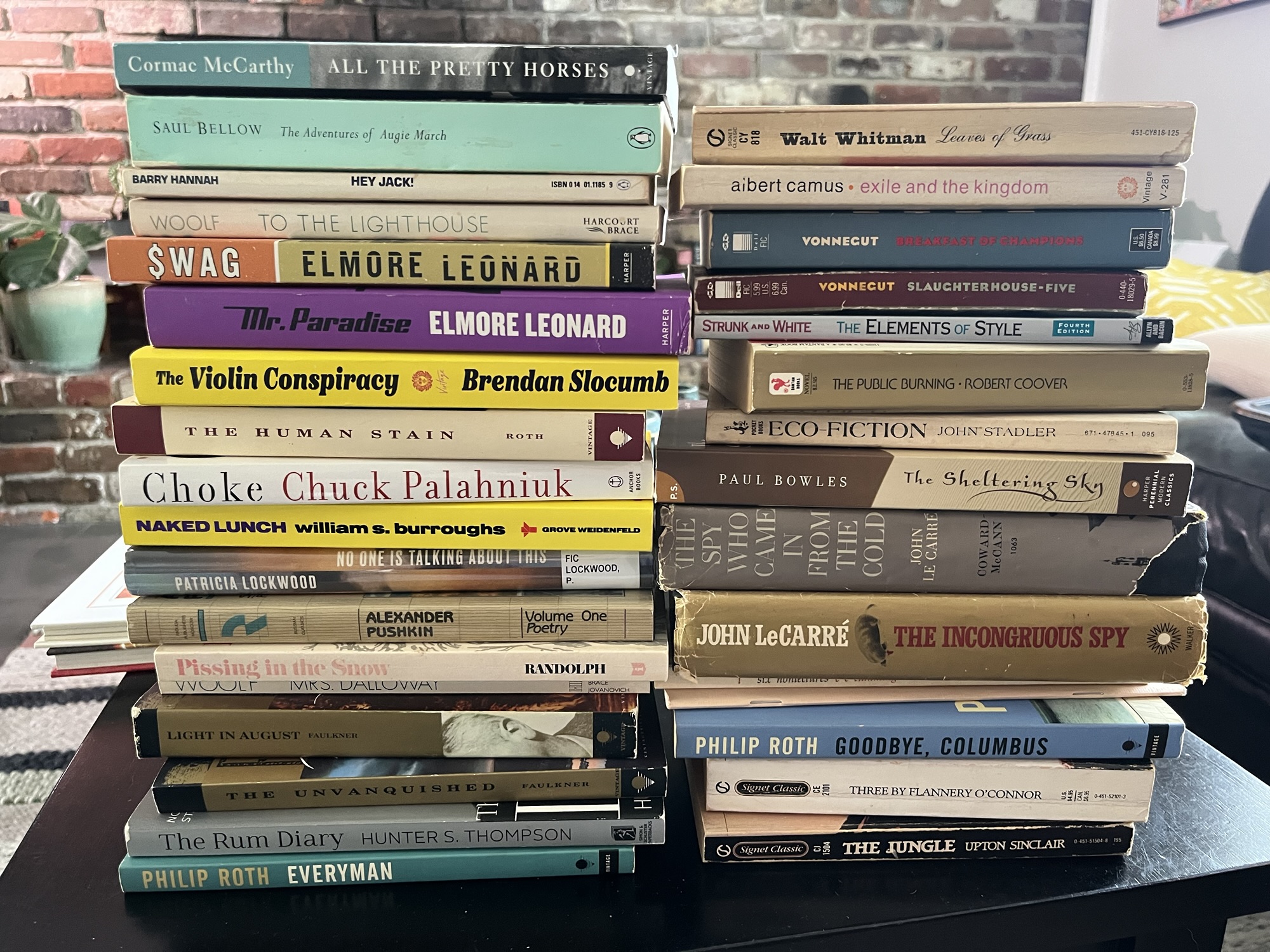

My move over the last few years when I go to a Friends of the Library Sale is to fill the ten dollar paper bag with a handful of pristine trade paperbacks I think will recoup the ten bucks in trade at my local used bookstore. I then pick through for titles to bolster my children’s growing personal libraries and for books that I might want to give away to friends, family, and students. And maybe I might get lucky with some overlooked gem — a first edition, a rarity, an oddity.

Most of what I picked up today was for my son to pick through. He took the Camus, Vonnegut, O’Connor, Palahniuk, and McCarthy. My daughter had zero interest in any of the haul.

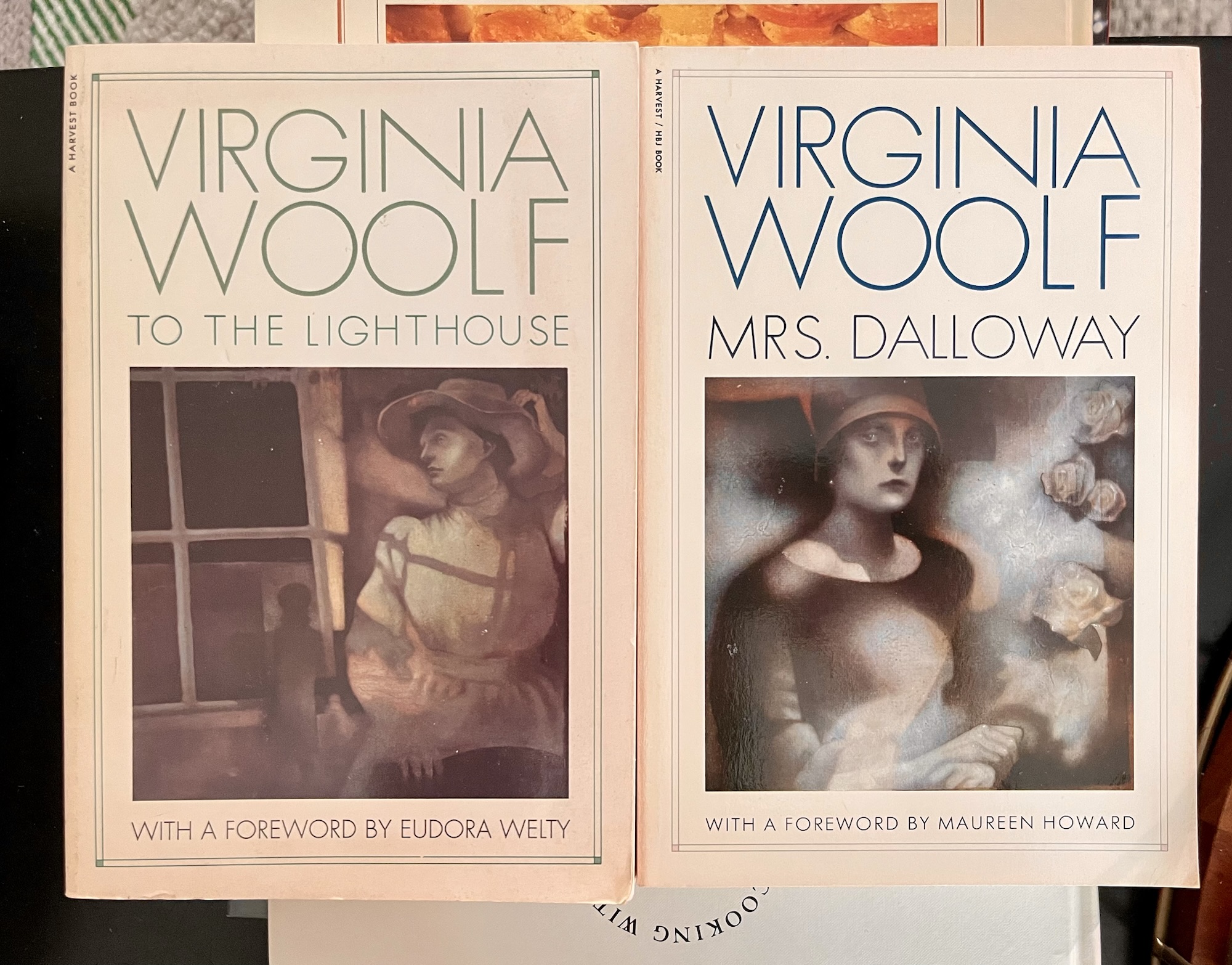

I wound up with several of the exact same editions of titles I already own (Camus’ Exile and Kingdom; Faulkner’s A Light in August; William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch) and lots of books we already have in other editions, most of which I’ll give away or trade. But I’ll be happy to trade out the cheap mass markets of Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse I’ve had forever in favor of these HBJ Woolfs (Wolves?):

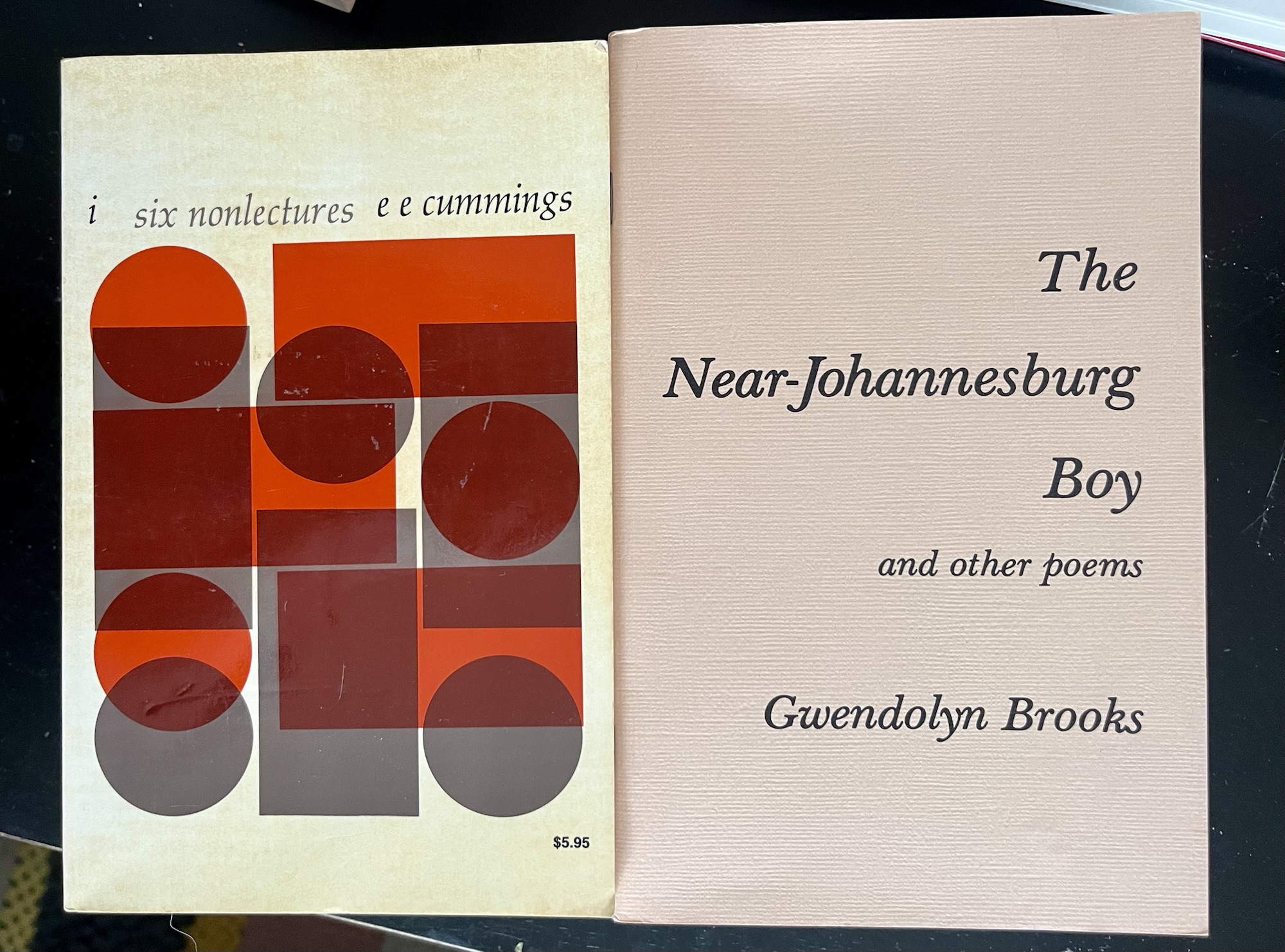

My two favorite finds today were cummings’ six nonlectures (the midcentury cover is lovely) and a Gwendolyn Brooks chapbook, The Near-Johannesburg Boy:

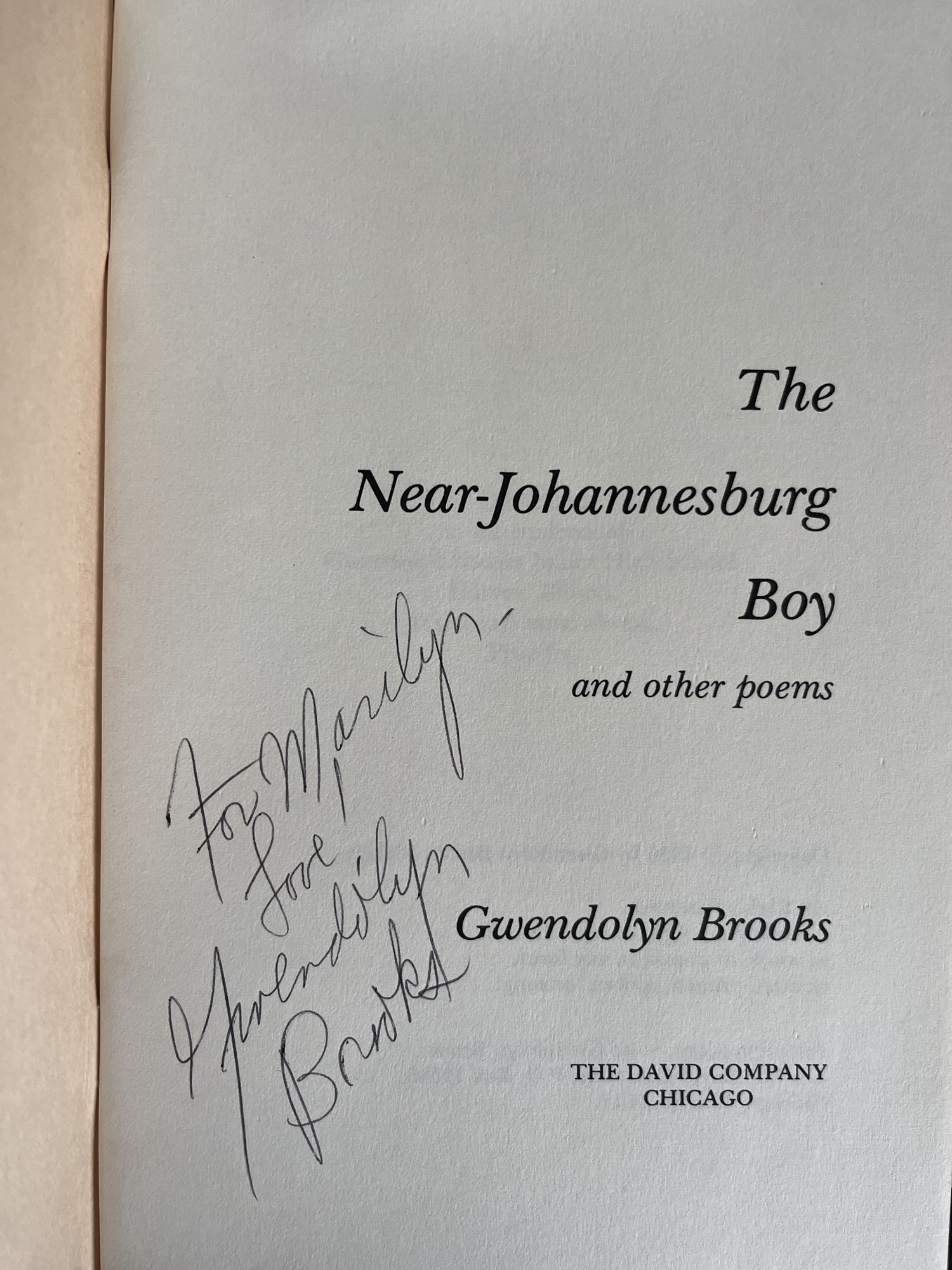

It wasn’t until I got home that I realized the Brooks’ chapbook was signed:

I had actually found two signed Brooks’ books at my favorite local used shop, also both inscribed to “Marilyn” (one was Blacks; I can’t remember the other one; they were both priced a bit beyond my casual range).

But maybe my favorite find was this Kmart bookmark:

The Kmart bookmark was tucked into a trade paperback University of Illinois Press copy of Randolph’s Pissing in the Snow. I doubt the collection of Ozark folktales was originally purchased at Kmart. But who knows.

Pissing in the Snow was one of the first books I wrote about on this blog, nearly twenty years ago. I look forward to passing it on to a student sooner or later.

The Workers’ May-Pole, 1894 by Walter Crane (1845-1915)

Here are 873 words from Stephen Dixon’s long looping loopy lucid antilaconic 1991 novel Frog; the words are a segment of the ninth chapter, “Frog’s Brother”:

Alex was the only passenger on the freighter. His father’s patient called his son in England and asked as a favor to the man who’s treated his family’s teeth for forty years if he could take Alex aboard free. Alex was in London then, wanted to get back home, had little money, could have borrowed plane or ocean liner fare from his parents or Jerry, wanted the experience of being on a freighter during a long crossing. Though he got free passage, he asked to work without pay at any job the captain wanted him to. He’ll clean latrines, even, he said in his last letter to Howard. Anything the lowest-grade seaman does, just to get the full feel of it and perhaps seaman’s papers for a paid trip later. He was a newsman turned fiction writer. Two months after the ship disappeared a parcel of manuscripts arrived at their parents’ apartment from England by surface mail. Maybe the manuscripts he didn’t much care about. Maybe the ones he cared most about he took with him on the ship. Howard read the stories and vignettes soon after and then some of them every three or four years till about ten years ago. He never found them very good, but Alex was just starting. Two diaries and some oriental figurines in the parcel also, and lots of letters from his parents, brothers, friends. He’d traveled around the world. Saved up for three years to do it. Did it for a year. A prostitute in a dilapidated hut in a small village outside Bangkok. Why’s that experience come to mind first? It was in a letter to Howard, not the diaries. He searched the diaries for it, thinking an elaboration of it might be interesting, revealing, sexually exciting. She was fourteen years old. That made Alex sad. She asked him to marry her. She said she’d be devoted, would learn to cook and make love American, bear him many children if he wanted, all boys if he wanted (she knew how), would return to grade school. He gave her his silver ID bracelet, pleaded with her to give up prostitution. Then he did it a third time with her the same day and came back the next. Talk about hypocrisy! he said. What’s the trick of turning a customer into a suitor? he asked. But one who’ll be good to her and an adequate provider. If he knew, he’d give it to her. Sent her a pearl necklace from Manila. If he got a venereal disease from her he’d worry more about her than himself. He might go back for her before he leaves for India, or send for her once he gets back to America, and maybe even marry her when she comes of age. Keep this between them just in case it does happen. Taught English to Malaysian businessmen for a month. Met two old men in New Guinea—Canadians—who were living the primitive jungle life. They were good friends of his till they tried to drug and rape him. He’s afraid he had to kick them both in the balls to get out of there and then steal their canoe to get back to town. Fell in love with a witch. Read Proust’s Remembrances in five nearly sleepless days, an experience that’s left him dreaming of the books every night for the last six weeks. A Goan fortuneteller told him his trip would end badly. He said to go home by plane, don’t sail. Remind him when the time comes, for the man wouldn’t take any money. Had a fifteen-year-old girl in Nairobi. What can he tell Howard?—he likes young girls. It’s more than just the way their hair blows and breasts point and bellybuttons dimple and thighs are so even. Maybe it’s because of all the girls who barely let him pet them when he was a teenager. Rode a camel through part of the Sahara. Ate lizard, locusts, grasshoppers, grubs. Never felt very Jewish before till he started hitting all the old synagogues and Jewish cemeteries he could find in the Orient and Middle East. Wait’ll he gets to Poland and Prague and also tries to look the old families up. He’s afraid it’s converted him, but not to the point of wearing a skullcap. Hitchhiked with a sixteen-year-old sabra through Turkey and Yugoslavia, though she might have been younger. When she had to go back she said she thinks he got her pregnant—her device wasn’t put in right a few times, she was so new at it. He told her he’s heard that one before, but if she has the baby and the calendrical configurations fix it as his, or just if she still says it is, he’ll love and provide for it, adopt it if she wishes and take it to America with or without her or emigrate to Israel if she prefers, marry her if that’s what she wants—she’s quite striking and clever and potentially very artistic and smart. He’s written what he thinks is fairly decent work recently, he said in his last letter. He’s glad he’s found something he wants to do for the next twenty to thirty years, has Howard?

The titular “Frog’s Brother” is Alex. (“Frog,” by the way, is “Howard,” the protagonist of Frog.) Alex’s freighter goes missing in the North Atlantic; the ship is never recovered nor are lifeboats. No bodies. The only evidence of the disaster is absence.

In this absence, Frog imagines and reimagines Alex’s death at sea in different looping cycles; these reimaginings are also framed within Frog’s attempt to accurately recall his receiving the news that his brother Alex is lost at sea–was it by phone, that he received this awful news? in his other brother’s apartment? what were the specific conditions of this heartbreak?

Imagining and then reimagining the specific details of a horrifying, horrible, horrendous event is the rhetorical gist of Dixon’s 1995 follow-up to Frog, Interstate, a fucked-up eight-way riff on the narrator’s daughter’s murder by way of random highway violence.

I have read around 120 of Fog’s near 800 pages, and many of those pages feature the same rhetorical and narratological techniques or repetitions with differences that were so off-centered in Interstate: fraying phrases, looping tics, paranoid passages. In the absence of the one thing, Dixon’s narrators pony up iteration after iteration, something after something. But the narrators know that there’s not enough somethings to ever even come close to approximating everything. The iterations sharpen and highlight the beauty of the absence’s abyss.

That abyss was real, or true, or True, for Stephen Dixon, whose brother “Jimmy, a magazine writer, died in 1960 when the freighter he was on in the North Atlantic disappeared,” as the New York Times reported in Dixon’s 2019 obituary. The Times obituary continued: “Mr. Dixon felt that he was continuing his brother’s work. Jimmy Dixon had a short story published after his death.” If Jimmy Dixon was prototype to Alex Frogbrother, what are we to make of the fantastic paraphrase of his letters, above? The passage reads like a bizarre failed adventure tale, something we might expect from William T. Vollmann, who, with his heart of gold, tried to “free” sex workers. It’s also quite queasy when it comes to sex (a constant I’ve noticed in Dixon): “What can he tell Howard?—he likes young girls,” our narrator flatly, grossly reports.

The saddest and realest bit might be this though, the admission that “Howard read the stories and vignettes soon after and then some of them every three or four years till about ten years ago. He never found them very good, but Alex was just starting.” But Alex was just starting. The last bit of the section, “He’s glad he’s found something he wants to do for the next twenty to thirty years, has Howard?” seems both boon and curse, a door that opens and shuts simultaneously, cursing our Stephen Dixon, our Frog, to write write write write write write write write write…

“Painter and Magician”

by

Alice Rahon

From Surrealist Women: An International Anthology (ed. Penelope Rosemont). The text is from the catalog, Alice Rahon, Willard Gallery, New York, 1951

In earliest times painting was magical; it was the key to the invisible. In those days the value of a work lay in its powers of conjuration, a power that talent alone could not achieve. Like the shaman, the sibyl, and the wizard, the painter had to make himself humble, so that he could share in the manifestation of spirits and forms. The rhythm of our life today denies the primordial principle of painting; conceived in contemplation, the emotional content of of the picture cannot be perceived without contemplation.

The invisible speaks to us, and the world it paints takes the form of apparitions; it awakens in each of us that yearning for the marvelous and shows us the way back to it—the way that is the great conquest of childhood, and which is lost to us with the rational concepts of education.

Perhaps we have seen the Emerald City in some faraway dream that belongs to the common emotional fund of man. Entering by the gate of the Seven Colors, we travel along the Rainbow.

Radio Free Albemuth, 1985, Philip K. Dick. Avon Bard (1987). Cover art by Ron Walotsky. 212 pages.

From Philip K. Dick’s posthumous (and likely never-fully revised) novel Radio Free Albemuth:

The human being has an unfortunate tendency to wish to please.

I was in effect exactly like those captured Americans: a prisoner of war. I had become that in November 1968 when F.F.F. got elected. So had we all; we now dwelt in a very large prison, without walls, bounded by Canada, Mexico, and two oceans. There were the jailers, the turnkeys, the informers, and somewhere in the Midwest the solitary confinement of the special internment camps. Most people did not appear to notice. Since there were no literal bars or barbed wire, since they had committed no crimes, had not been arrested or taken to court, they did not grasp the change, the dread transformation, of their situation. It was the classic case of a man kidnapped while standing still. Since they had been taken nowhere, and since they themselves had voted the new tyranny into power, they could see nothing wrong. Anyhow, a good third of them, had they known, would have thought it w

as a good idea. As F.F.F. told them, now the war in Vietnam could be brought to an honorable conclusion, and, at home, the mysterious organization Aramchek could be annihilated. The Loyal Americans could breathe freely again. Their freedom to do as they were told had been preserved.I returned to the typewriter and drafted another statement. It was important to do a good job.

Study for Official Portrait #3 (Pillars of Society), 2018 by Jim Shaw (b. 1952)

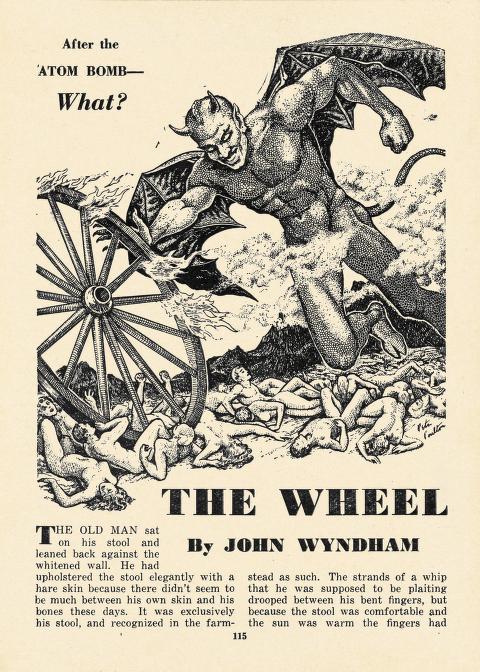

“The Wheel”

by

John Wyndham

THE OLD MAN sat on his stool and leaned back against the whitened wall. He had upholstered the stool elegantly with a bare skin because there didn’t seem to be much between his own skin and his bones these days. It was exclusively his stool, and recognized in the farmstead as such. The strands of a whip that he was supposed to be plaiting drooped between his bent fingers, but because the stool was comfortable and the sun was warm the fingers had stopped moving, and his head was nodding.

The yard was empty save for a few hens that pecked more inquisitively than hopefully in the dust, but there were sounds that told of others who had not the old man’s leisure for siesta. From round the corner of the house came the occasional plonk of an empty bucket as it hit the water, and its scrape on the side of the well as it came up full. In the shack across the yard a dull pounding went on rhythmically and soporifically.

The old man’s head fell further forward as he drowsed.

Presently, from beyond the rough, enclosing wall there came another sound, slowly approaching. A rumbling and a rattling, with an intermittent squeaking. The old man’s ears were no longer sharp, and for some minutes it failed to disturb him. Then he opened his eyes and, locating the sound, sat staring incredulously toward the gateway.

The sound drew closer, and a boy’s head showed above the wall. He grinned at the old man, an expression of excitement in his eyes. He did not call out, but moved a little faster until he came to the gate. There he turned into the yard, proudly towing behind him a box mounted on four wooden wheels.

The old man got up suddenly from his seat, alarm in every line. He waved both arms at the boy as though he would push him back. The boy stopped. His expression of gleeful pride faded into astonishment. He stared at the old man who was waving him away so urgently. While he still hesitated the old man continued to shoo him off with one hand as he placed the other on his own lips, and started to walk towards him.

Reluctantly and bewilderedly the boy turned, but too late. The pounding in the shed stopped. A middle-aged woman appeared in the doorway. Her mouth was open to call, but the words did not come. Her jaw dropped slackly, her eyes seemed to bulge, then she crossed herself, and screamed….

Continue reading ““The Wheel,” a short story by John Wyndham”

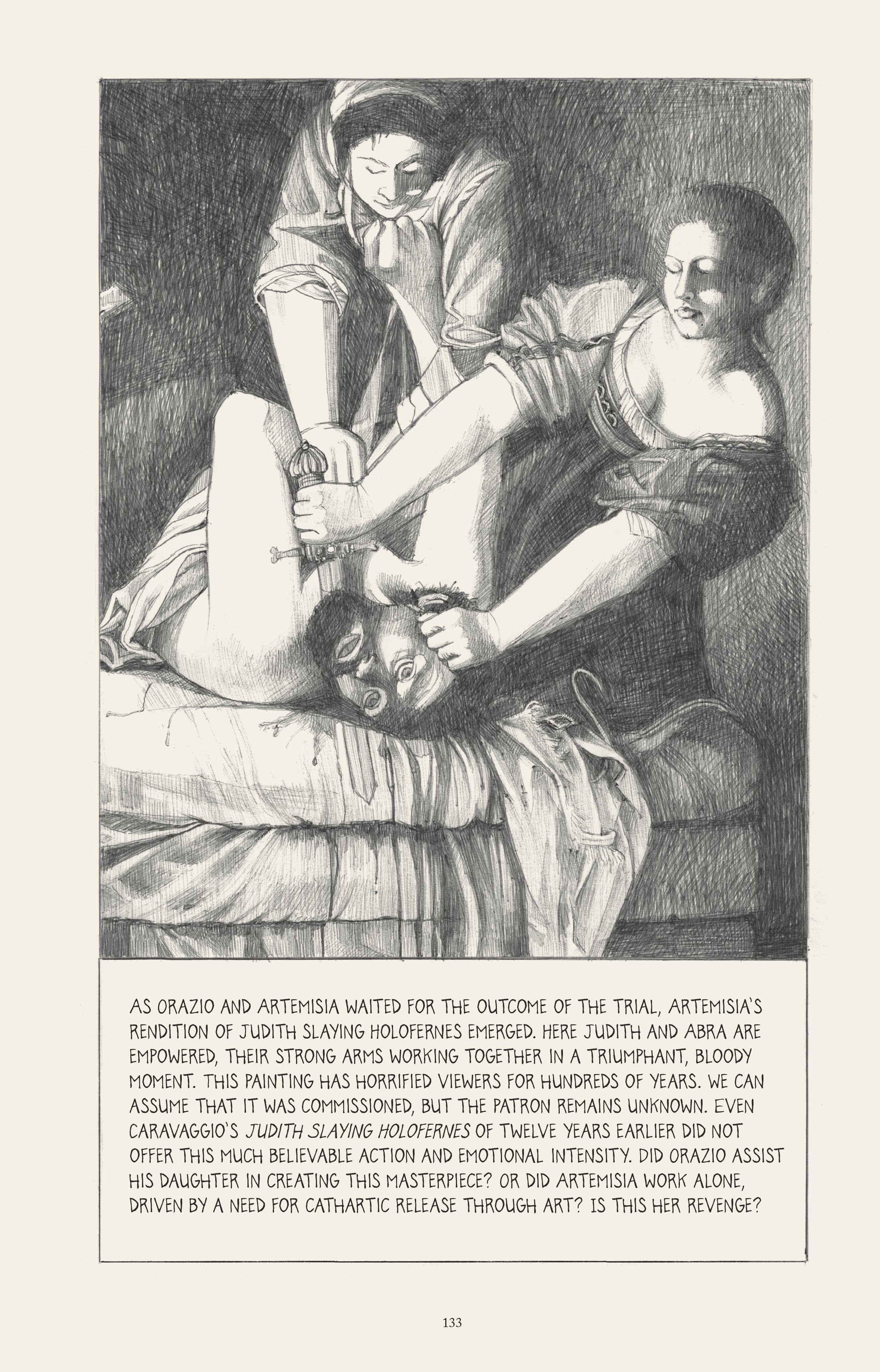

Judith Slaying Holofrenes (After Artemisia Gentileschi) by Gina Siciliano. From Siciliano’s brilliant biography, I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi.

Matt Bucher’s forthcoming novel The Summer Layoff is a semi-sequel to his debut, The Belan Deck. Blurb:

On Day 1, the narrator of The Summer Layoff is unceremoniously canned from his soul-sucking corporate job. But, he has a generous severance package that affords him the time off to do nothing, for once. Instead of attending virtual meetings and reviewing PowerPoint files relating to an amorphous Al project, he can now take long walks through his Texas suburb, write in his diary, scroll Wikipedia for hours at a time, and contemplate normal human anxieties. Part catalog, part self-help note-to-self, The Summer Layoff is a meditation on the modern metaphysics of work and stasis.

From my review of The Belan Deck:

Let’s talk about the spirit and form of The Belan Deck. Bucher borrows the epigraphic, anecdotal, fractured, discontinuous style that David Markson practiced (perfected?) in his so-called Notecard Quartet (1996-2007: Reader’s Block, This Is Not A Novel, Vanishing Point, and The Last Novel). “An assemblage…nonlinear, discontinuous, collage-like,” wrote Markson, to which Bucher’s narrator replies, “Bricolage. DIY culture. Amateurism. Fandom. Blackout poems.”

Bucher’s bricolage picks up Markson’s style and spirit, but also moves it forward. Although Markson’s late quartet is arguably (I would say, by definition) formally postmodernist, the object of the Notecard Novels’ obsession is essentially Modernism. Bucher’s book is necessarily post-postmodern, taking as its objects the detritus and tools of postmodern communication: PowerPoint, Google Street View, Wikipedia, social media, artificial intelligence.