Vladimir Sorokin’s novel Their Four Hearts (in English translation by Max Lawton) made me physically ill several times. To be clear, the previous statement is a form of praise. I finished it a few weeks ago and put it on a high shelf where no one in my family might come across it.

I picked up Their Four Hearts on the strength of the first Sorokin novel I read, Telluria, and the third, Blue Lard (both also in translation by Max Lawton). The kinetic energy of those novels evoked cinema in my mind’s eye—something akin to Alejandro Jodorowsky’s surreal Holy Mountain or Luis Buñuel’s comic masterpiece L’Age d’Or—narratives that engender their own new visual grammars. In Their Four Hearts, I again found a cinematic comparison, this time in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s study of depravity and cruelty, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.

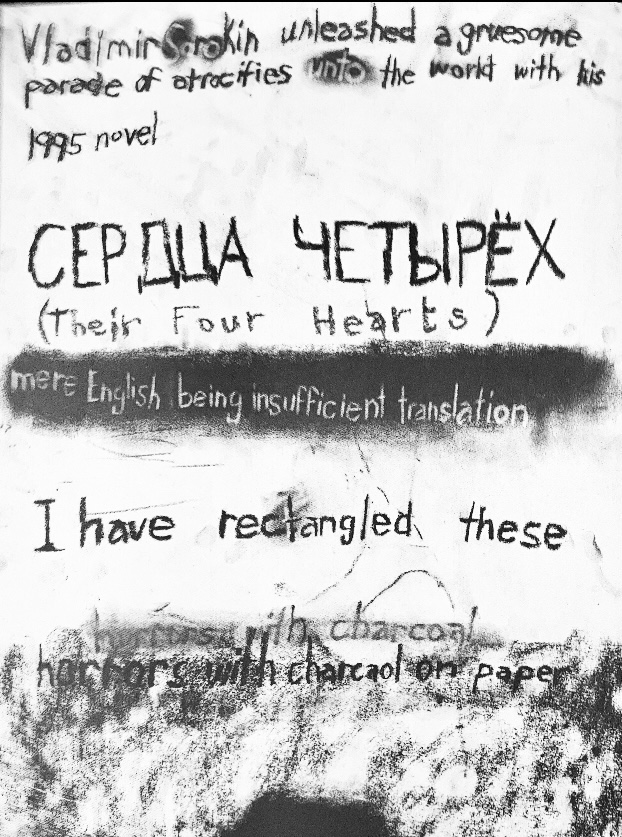

Like Salò, Sorokin’s Their Four Hearts explores seemingly every form of depravity in extreme detail. It is not for the faint of heart or stomach. (Sorokin’s potent language, in Lawton’s sharp translation, would eviscerate the cliches that precede this parenthetical aside.) Their Four Hearts is fairly short—200 pages, including over 30 pages of charcoal illustrations by Greg Klassen—but I had parcel it out over four distinct sittings. (After the second time I had to put it down because of nausea, I decided to avoid reading it close to mealtimes.)

Before I touch briefly on that depravity, it might be useful to interested readers to offer a gloss on the plot of Their Four Hearts. There is no recognizable plot. Or, rather, the plot hides behind the accumulation of violent, abject details, forever unavailable to a reader, no matter how keen a detective that reader might be. It is a cannibalizing plot, both literally and figuratively, stochastic, absurd, consuming its own horrific iterations.

But, like, what is it about?, hypothetical you might ask. In lieu of a list of depravities, let me cannibalize the back cover copy:

Their Four Hearts follows the violent and nonsensical missions carried out by a group of four characters who represent Socialist Realist archetypes: Seryozha, a naive and optimistic young boy; Olga, a dedicated female athlete; Shtaube, a wise old man; and Rebrov, a factory worker and a Stakhanovite embodying Soviet manhood. However, the degradation inflicted upon them is hardly a Socialist Realist trope. Are the acts of violence they carry out a more realistic vision of what the Soviet Union forced its “heroes” to live out? A corporealization and desacralization of self-sacrificing acts of Soviet heroism? How the Soviet Union truly looked if you were to strip away the ideological infrastructure? As we see in the long monologues Shtaube performs for his companions––some of which are scatological nonsense and some of which are accurate reproductions of Soviet language––Sorokin is interested in burrowing down to the libidinal impulses that fuel a totalitarian system and forcing the reader to take part in them in a way that isn’t entirely devoid of aesthetic pleasure.

Libidinal forces . . . totalitarian system . . . forcing the reader . . . aesthetic pleasure?

Aesthetic pleasure? Pleasure is doing a lot in that phrase, although I was admittedly alternately rapt by Their Four Hearts even while I was (quite literally) disgusted. I’ve read enough Sorokin to this point that I didn’t have to be forced into the surreal, jarring logic of the plot, finding instead deeply dark humor in it, where possible (although more often than not, horror without humor).

I have resisted turning this ostensible “review” into a catalog of the horrors Sorokin offers in Their Four Hearts. These horrors are all the more horrible for their sensory evocation set against their seemingly senseless (lack of) meaning. When the foursome, very early in the novel, drug and murder Seryozha’s parents, remove the glans from his father’s penis, and pop into the kid’s mouth to suck on, does that mean something exterior to the novel’s own aesthetics? That the quartet continues to trade the glans off, taking turns sucking on it throughout the novel—are we to plumb that for some kind of allegorical gloss? Or do we simply ride with it? Their Four Hearts confounds its readers, creating not only its own inventions of vocabulary, but its own grammar of storytelling.

Instead of my describing further the horrors of Their Four Hearts (murder, pedophilia, parricide, torture, mutilation, coprophagia, rape, cannibalism, etc. ), it might be more profitable for interested readers to inspect the illustrations by Greg Klassen I’ve included in this review. Reminiscent of George Grosz or Hans Bellmer, Klassen’s charcoals capture the tone and vibe of Their Four Hearts. They add to the text’s cinematic quality. (Publisher Dalkey Archive should have given Klassen the cover.)

By now you likely have a clear idea if Their Four Hearts is For You or Not For You. I found the experience of reading Sorokin’s novel paradoxically compelling and repellent. (One of the closest experiences I can compare reading it to was eating beef chitterlings at a Korean restaurant in Tokyo. The waitress brought the raw gray intestines to our table, where we grilled them ourselves over charcoal, dipping them in sauces. We ate three orders.)

Telluria and the forthcoming Blue Lard are much better starting places for those interested in Sorokin, but his translator Lawton suggested in an interview that,

…any new reader of Sorokin [should] immediately chase TELLURIA with THEIR FOUR HEARTS: those two combined give something like a complete picture of the master at work.

It’s a strange chaser, and it leaves a flavor unlike anything else I’ve ever tasted. Highly recommended.