“A Christmas Number” — A.A. Milne

The common joke against the Christmas number is that it is planned in July and made up in September. This enables it to be published in the middle of November and circulated in New Zealand by Christmas. If it were published in England at Christmas, New Zealand wouldn’t get it till February. Apparently it is more important that the colonies should have it punctually than that we should.

Anyway, whenever it is made up, all journalists hate the Christmas number. But they only hate it for one reason—this being that the ordinary weekly number has to be made up at the same time. As a journalist I should like to devote the autumn exclusively to the Christmas number, and as a member of the public I should adore it when it came out. Not having been asked to produce such a number on my own I can amuse myself here by sketching out a plan for it. I follow the fine old tradition. First let us get the stories settled. Story No. 1 deals with the escaped convict. The heroine is driving back from the country- house ball, where she has had two or three proposals, when suddenly, in the most lonely part of the snow-swept moor, a figure springs out of the ditch and covers the coachman with a pistol. Alarms and confusions. “Oh, sir,” says the heroine, “spare my aunt and I will give you all my jewels.” The convict, for such it is, staggers back. “Lucy!” he cries. “Harold!” she gasps. The aunt says nothing, for she has swooned. At this point the story stops to explain how Harold came to be in knickerbockers. He had either been falsely accused or else he had been a solicitor. Anyhow, he had by this time more than paid for his folly, and Lucy still loved him. “Get in,” she says, and drives him home. Next day he leaves for New Zealand in an ordinary lounge suit. Need I say that Lucy joins him later? No; that shall be left for your imagination. The End.

So much for the first story. The second is an “i’-faith-and-stap- me” story of the good old days. It is not seasonable, for most of the action takes place in my lord’s garden amid the scent of roses; but it brings back to us the old romantic days when fighting and swearing were more picturesque than they are now, and when women loved and worked samplers. This sort of story can be read best in front of the Christmas log; it is of the past, and comes naturally into a Christmas number. I shall not describe its plot, for that is unimportant; it is the “stap me’s” and the “la, sirs,” which matter. But I may say that she marries him all right in the end, and he goes off happily to the wars.

We want another story. What shall this one be about? It might be about the amateur burglar, or the little child who reconciled old Sir John to his daughter’s marriage, or the ghost at Enderby Grange, or the millionaire’s Christmas dinner, or the accident to the Scotch express. Personally, I do not care for any of these; my vote goes for the desert-island story. Proud Lady Julia has fallen off the deck of the liner, and Ronald, refused by her that morning, dives off the hurricane deck—or the bowsprit or wherever he happens to be—and seizes her as she is sinking for the third time. It is a foggy night and their absence is unnoticed. Dawn finds them together on a little coral reef. They are in no danger, for several liners are due to pass in a day or two and Ronald’s pockets are full of biscuits and chocolate, but it is awkward for Lady Julia, who had hoped that they would never meet again. So they sit on the beach back to back (drawn by Dana Gibson) and throw sarcastic remarks over their shoulders at each other. In the end he tames her proud spirit—I think by hiding the turtles’ eggs from her—and the next liner but one takes the happy couple back to civilization.

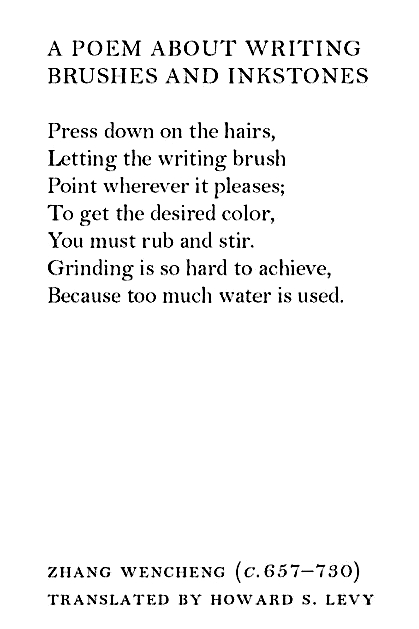

But it is time we had some poetry. I propose to give you one serious poem about robins, and one double-page humorous piece, well illustrated in colours. I think the humorous verses must deal with hunting. Hunting does not lend itself to humour, for there are only two hunting jokes —the joke of the horse which came down at the brook and the joke of the Cockney who overrode hounds; but there are traditions to keep up, and the artist always loves it. So far we have not considered the artist sufficiently. Let us give him four full pages. One of pretty girls hanging up mistletoe, one of the squire and his family going to church in the snow, one of a brokendown coach with highwaymen coming over the hill, and one of the postman bringing loads and loads of parcels. You have all Christmas in those four pictures. But there is room for another page—let it be a coloured page, of half a dozen sketches, the period and the lettering very early English. “Ye Baron de Marchebankes calleth for hys varlet.” “Ye varlet cometh righte hastilie—-” You know the delightful kind of thing.

I confess that this is the sort of Christmas number which I love. You may say that you have seen it all before; I say that that is why I love it. The best of Christmas is that it reminds us of other Christmases; it should be the boast of Christmas numbers that they remind us of other Christmas numbers.

But though I doubt if I shall get quite what I want from any one number this year, yet there will surely be enough in all the numbers to bring Christmas very pleasantly before the eyes. In a dull November one likes to be reminded that Christmas is coming. It is perhaps as well that the demands of the colonies give us our Christmas numbers so early. At the same time it is difficult to see why New Zealand wants a Christmas number at all. As I glance above at the plan of my model paper I feel more than ever how adorable it would be—but not, oh not with the thermometer at a hundred in the shade.