“Among the Beanwoods”

by

Donald Barthelme

The already-beautiful do not, as a rule, run.

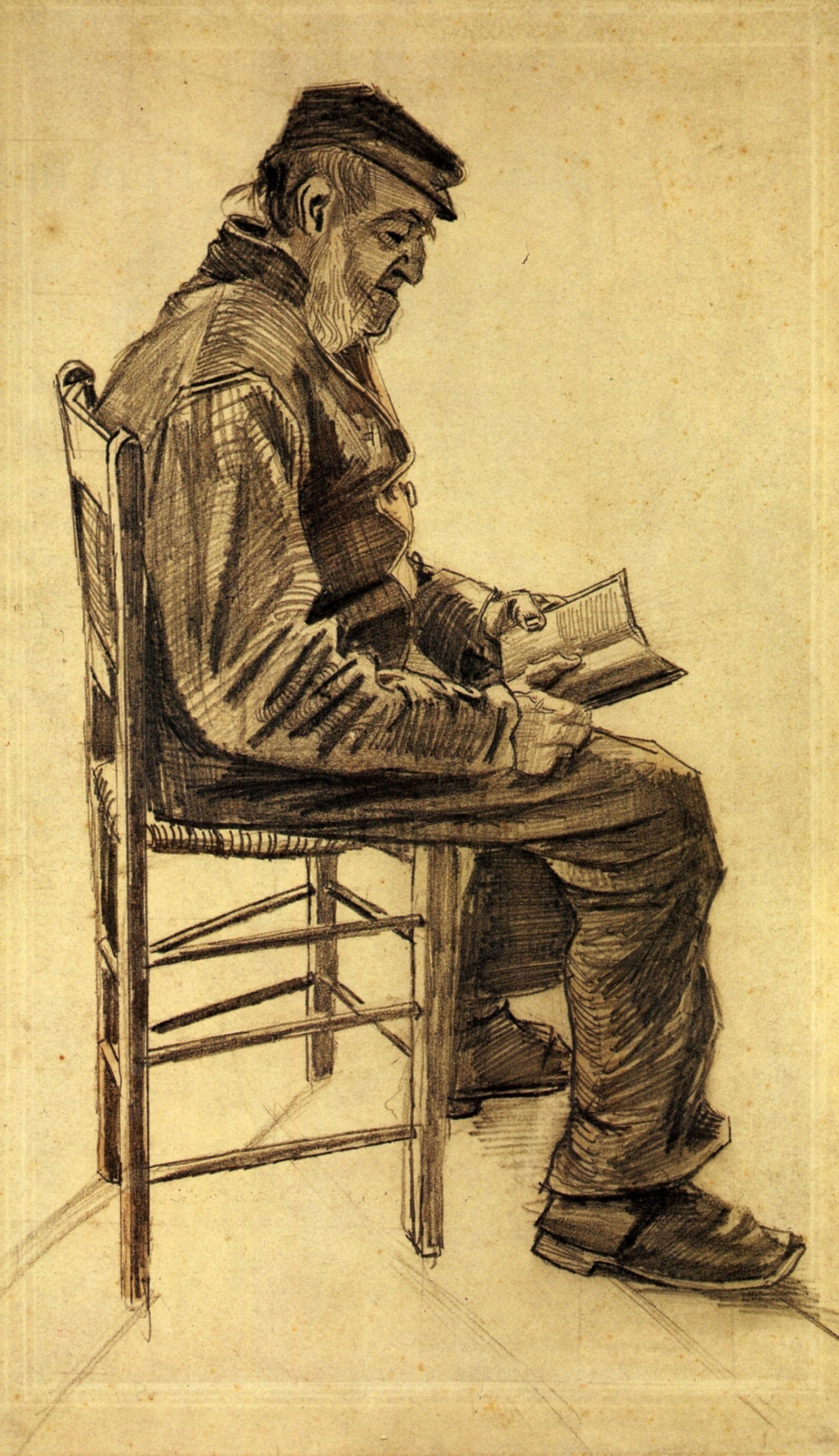

I am, at the moment, seated.

Ireland and Scotland are remote; Wales fares little better. Here in this forest of tall, white beanwoods, the already-beautiful saunter. Some of them carry plump red hams, already cooked.

I am, at the moment, seated. On a chair in the forest, listening. I will rise, shortly, to hold the ladder for you. Every beanwood will have its chandelier scattering light on my exercise machine, which is made of cane. The beans you have glued together are as nothing to the difficulty of working with cane, at night, in the dark, in the wind, watched by insects. I will not allow my exercise machine to be photographed. It sings, as I exercise, like an unaccompanied cello. I will not allow my exercise machine to be recorded.

Tombs are scattered through the beanwoods, made of perfectly ordinary gray stone. All are empty. The chandeliers, at night, scatter light over the tombs, little houses in which I sleep, from time to time, with the already-beautiful, and they with me. We call to each other, at night, saying “Hello, hello” and “Who, who, who?” That one has her hips exposed, for rubbing.

Holding the ladder, I watch you glue additional chandeliers to appropriate limbs. You are tiring, you have worked very hard. Iced beanwater will refresh you, and these wallets made of ham. I have been meaning to speak to you. I have set bronze statues of alert, crouching Indian boys around the periphery of the forest, for ornamentation. Each alert, crouching Indian boy is accompanied by a large, bronze, wolf-like dog, finely polished.

I have been meaning to speak to you. I have many pages of notes. I have a note about cameras, a note about recorders, a note about steel wool, a note about the invitations. On weightier matters I will speak without notes, freely and passionately, as if inspired, at night, in a rage, slapping myself, great tremendous slaps to the brow which will fell me to the earth. The already-beautiful will stand and watch, in a circle, cradling, each, an animal in mothering arms — green monkey, meadow mouse, tucotuco. That one has her hips exposed, for study. I make careful notes. You snatch the notebook from my hands.

The pockets of your smock swinging heavily with the lights of chandeliers. Your light-by-light, bean-by-bean career.

I am, at this time, prepared to dance. The already-beautiful have, historically, danced. The music made by my exercise machine is, we agree, danceable. The women partner themselves with large bronze hares, which have been cast in the attitudes of dancers. The beans you have glued together are as nothing to the difficulty of casting hares in the attitudes of dancers, at night, in the foundry, the sweat, the glare. Thieves have been invited to dinner, along with the deans of the great cathedrals. The thieves will rest upon the bosoms of the deans, at dinner, among the beanwoods. Soft benedictions will ensue.

I am privileged, privileged, to be able to hold your ladder.

Pillows are placed in the tombs, together with pot holders and dust cloths. The already-beautiful strut. England is far away, and France is scarcely nearer. I am, for the time being, reclining. In a warm tomb, with Concordia, who is beautiful. Mad with bean wine she has caught me by the belt buckle and demanded that I hear her times tables. Her voice enchants me. Tirelessly you glue. The forest will soon exist on some maps, a tribute to the quickness of the world’s cartographers. This life is better than any life I have lived, previously. I order more smoke, which is delivered in heavy glass demi-johns, twelve to a crate. Beautiful hips abound, bloom. Your sudden movement toward red kidney beans has proved, in the event, masterly. Everywhere we see formal gowns of red kidney beans, which have been polished to the fierceness of carnelians. No ham hash does not contain two beans, polished to the fierceness of carnelians.

Spain is distant, Portugal wrapped in an impenetrable haze. These noble beans, glued by you, are mine. Thousand-pound sacks are off-loaded at the quai, against our future needs. The thieves are willing workers, the deans, straw bosses of extraordinary tact. I polish hares, dogs, Indian boys in the chill of early morning. Your weather reports have been splendid. The fall of figs you predicted did in fact occur. There is nothing like ham in fig sauce, or almost nothing. I am, at the moment, feeling very jolly. Hey hey, I say. It is remarkable how well human affairs can be managed, with care.