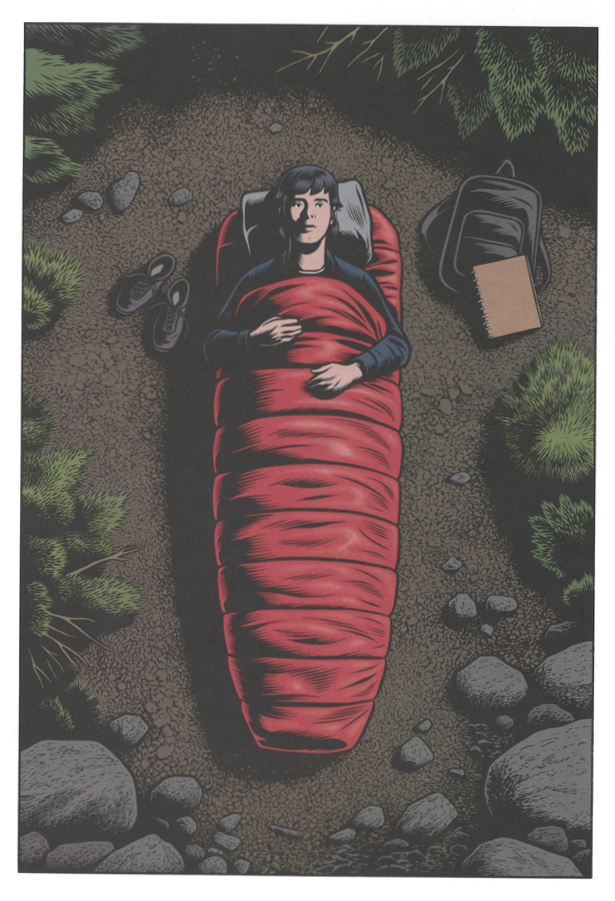

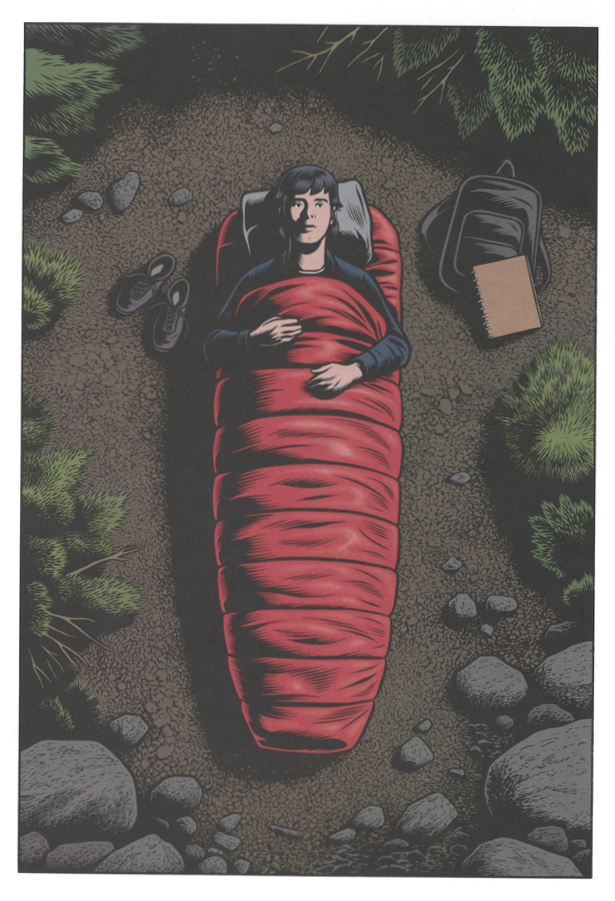

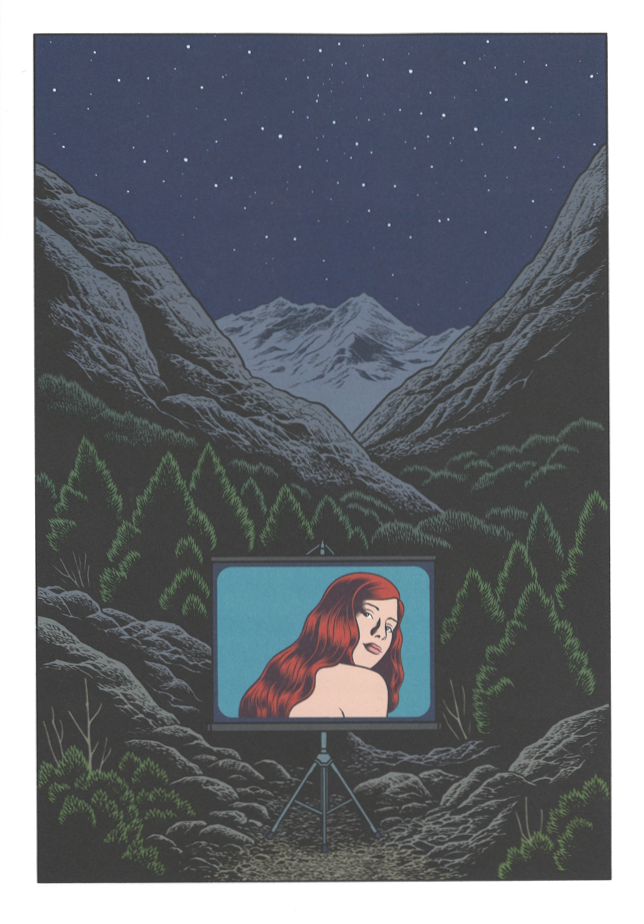

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel Final Cut tells the story of Brian, an obsessive would-be auteur grappling with an unrealized film project. Brian hopes to assemble his film — also titled Final Cut — from footage he shoots with friends on a weekend camping trip, but the messiness of reality impinges the weird glories of his vibrant imagination. He cannot bring his vision to the screen. He cannot capture all the “fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel Final Cut tells the story of Brian, an obsessive would-be auteur grappling with an unrealized film project. Brian hopes to assemble his film — also titled Final Cut — from footage he shoots with friends on a weekend camping trip, but the messiness of reality impinges the weird glories of his vibrant imagination. He cannot bring his vision to the screen. He cannot capture all the “fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”

Capturing all the fucked-up shit going on inside my head is a neat encapsulation of the Artistic Problem in general. It’s not that Brian doesn’t try; if anything, he tries too hard. His best friend and erstwhile cameraman Chris is there to help him, along with his crush Laurie and their friend Tina—but ultimately, these are still kids at play. They indulge Brian’s artistic whims, but at a certain point they’d rather swim, drink, and smoke than shoot yet another scene they can’t comprehend.

Capturing all the fucked-up shit going on inside my head is a neat encapsulation of the Artistic Problem in general. It’s not that Brian doesn’t try; if anything, he tries too hard. His best friend and erstwhile cameraman Chris is there to help him, along with his crush Laurie and their friend Tina—but ultimately, these are still kids at play. They indulge Brian’s artistic whims, but at a certain point they’d rather swim, drink, and smoke than shoot yet another scene they can’t comprehend.

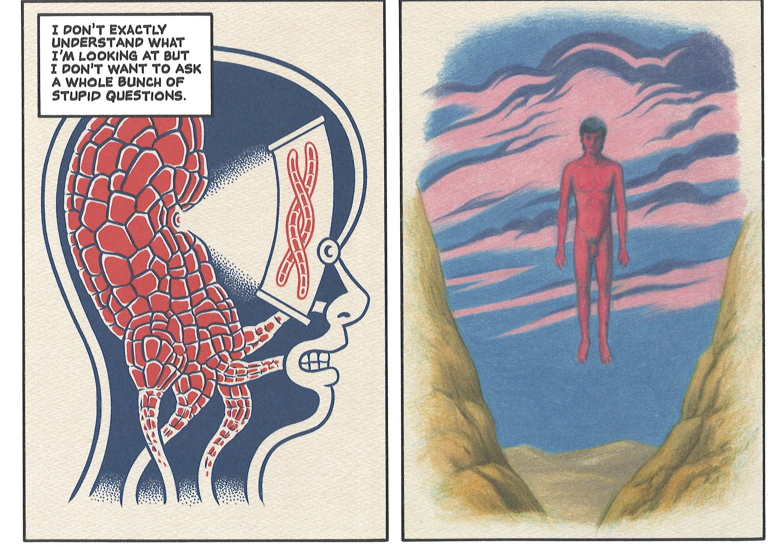

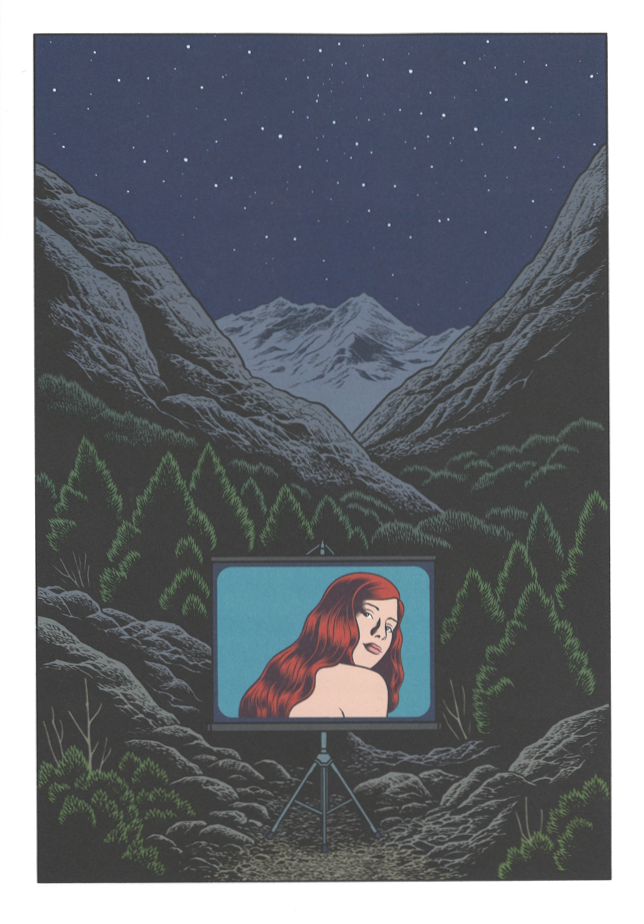

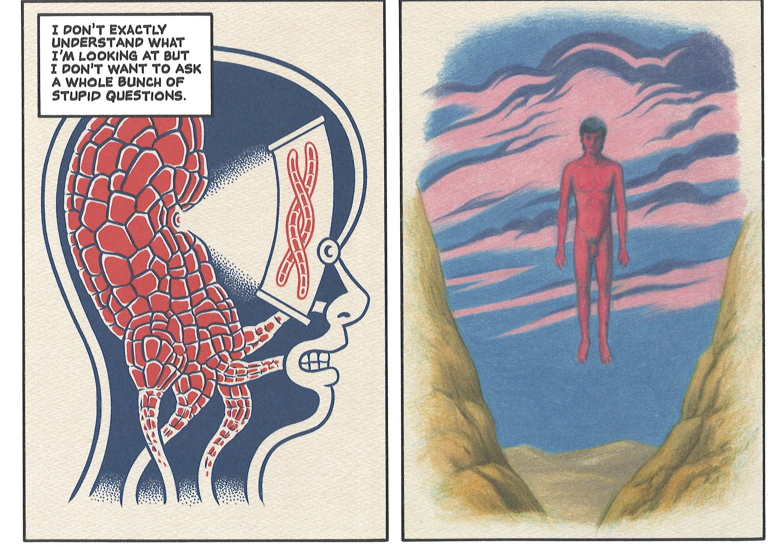

Eschewing straightforward narrative conventions, Final Cut unfolds in a blend of flashbacks, dreamscapes, and flights into Brian’s imagination. The book also gives over to Laurie’s consciousness, providing an essential ballast of realism to anchor Brian’s (and Burns’, I suppose) surrealism. Brian would have Laurie as his muse, trying to capture her in his sketchbook, in his film, and in the intense gaze of his mind’s eye. And while Laurie is fascinated by Brian’s visions, she doesn’t understand them.

The last member of Brian’s would-be acting troupe is Tina, an earthy, funny gal who drinks a bit too much. She plays foil to Brian’s ambitions; her animated spirit punctures the seriousness of his film shoot. Again, these are just kids in the woods with a camera and camping gear.

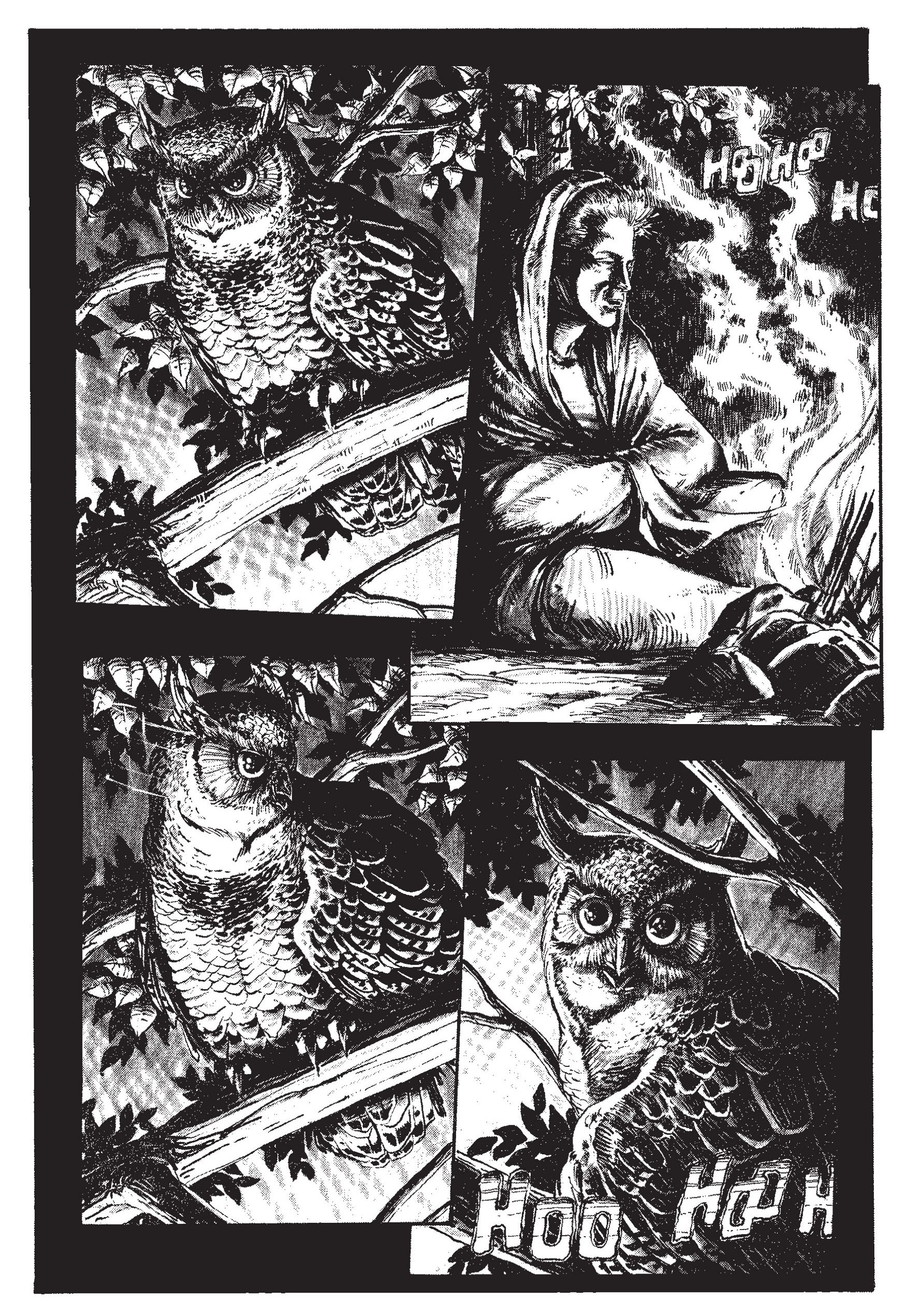

And the film itself? Well, it’s about kids camping in the woods. And an alien invasion. And pod people.

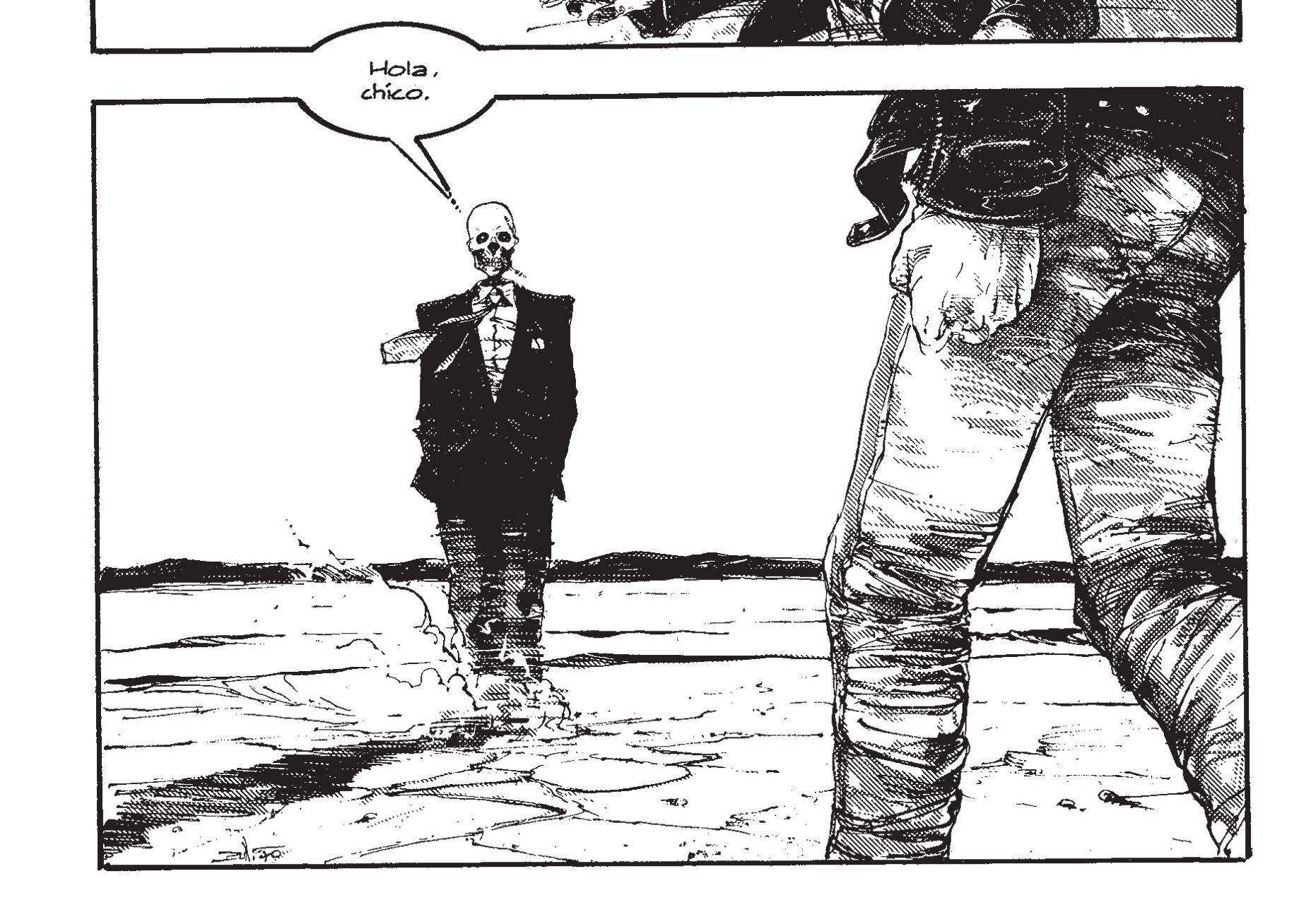

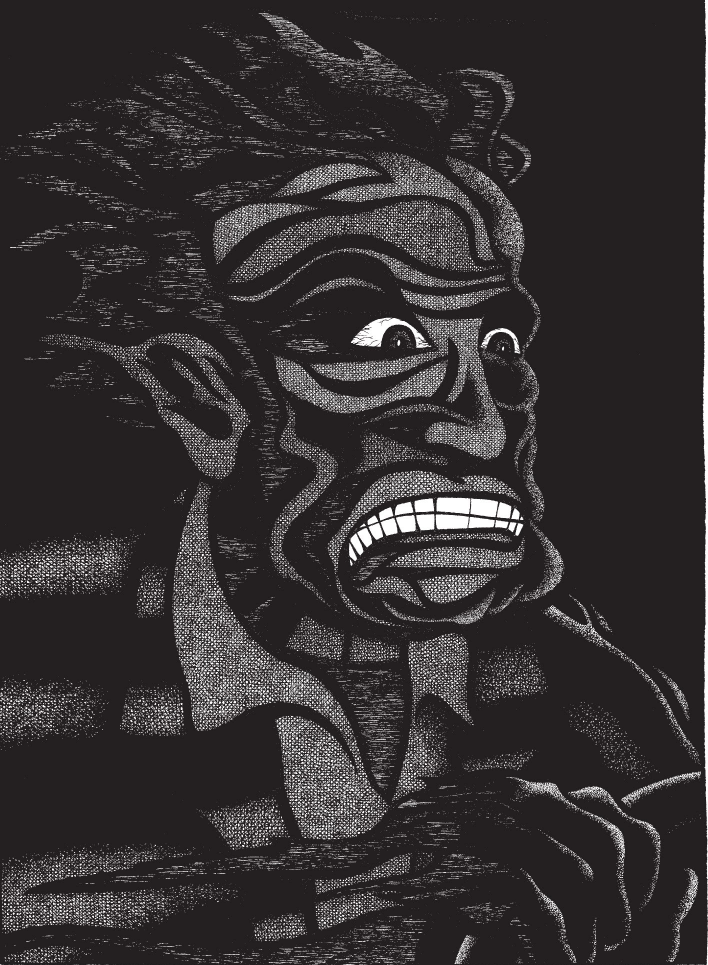

The pod-people motif dominates Final Cut. We get the teens in their larval sleeping bags, transformed into aliens in their cocoons (echoed again in Brian’s imagination and in his sketches). The motif looms larger: Can we really know who a person is? Could they be someone else entirely? Can we really ever know all the fucked-up shit going on inside their head?

Indeed, Don Siegel’s 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a major progenitor text for Final Cut. Brian even takes Laurie on a date to a screening of Invasion; he’s so mesmerized by the film that he weeps. Burns renders stills from the film in heavy chiaroscuro black and white, contrasting with the vibrant reds, maroons, and pinks that reverberate through the novel.

Burns recreates stills from another black and white film, Peter Bogdanovich’s 1971 coming-of-age heartbreaker The Last Picture Show. Again, Brian is obsessed with the film—or by the film, perhaps. In particular, he’s infatuated with Cybill Shepherd’s Jacy, whose character he imaginatively merges with his conception of Laurie.

While Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a science-fiction horror film, a deep sense of reality-soaked dread underpins it; The Last Picture Show is utterly real in its evocations of the emotional and physical lives of teenagers. Both films convey a maturity and balance of the fantastic with the real that Brian has not yet purchased via his own experiences, his own failures and heartbreaks.

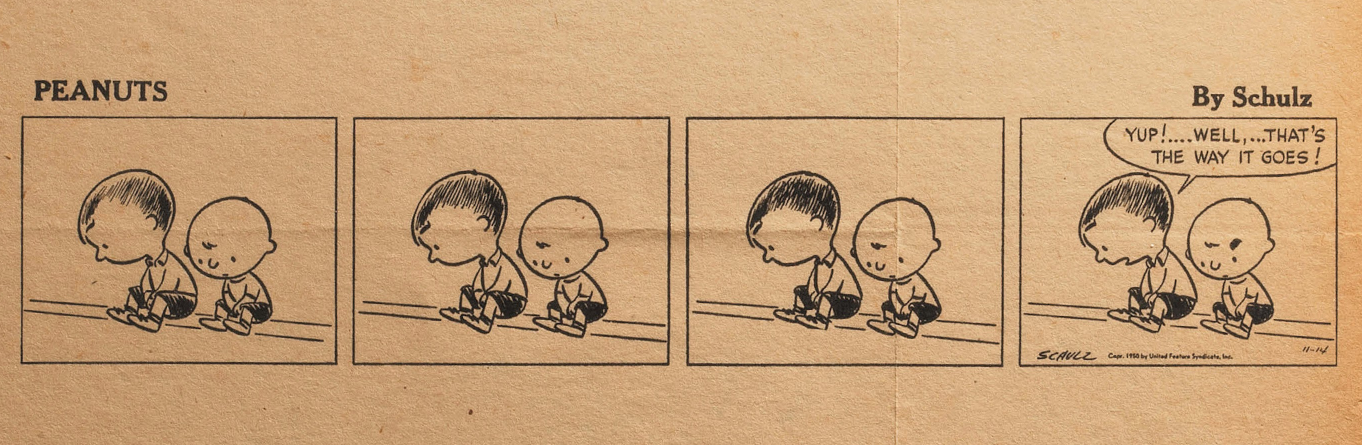

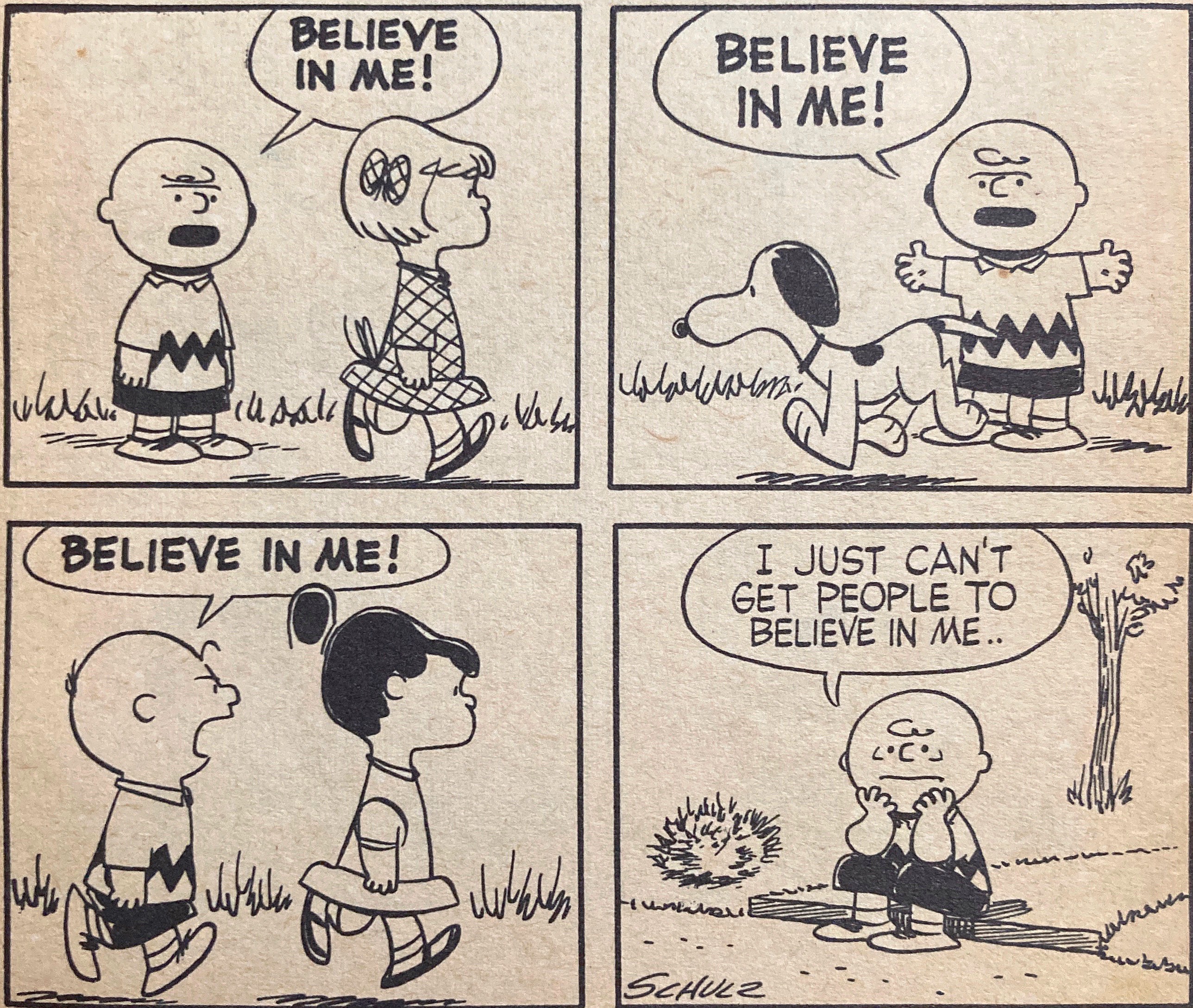

The maturity and balance that Brian can imagine but not execute in his Final Cut is precisely the maturity and balance that Burns achieves in his Final Cut. Simply put, Final Cut is the effort of a master performing at the heights of his power, rendered with inspired technical proficiency. It delivers on themes Burns has been exploring from the earliest days of his career.

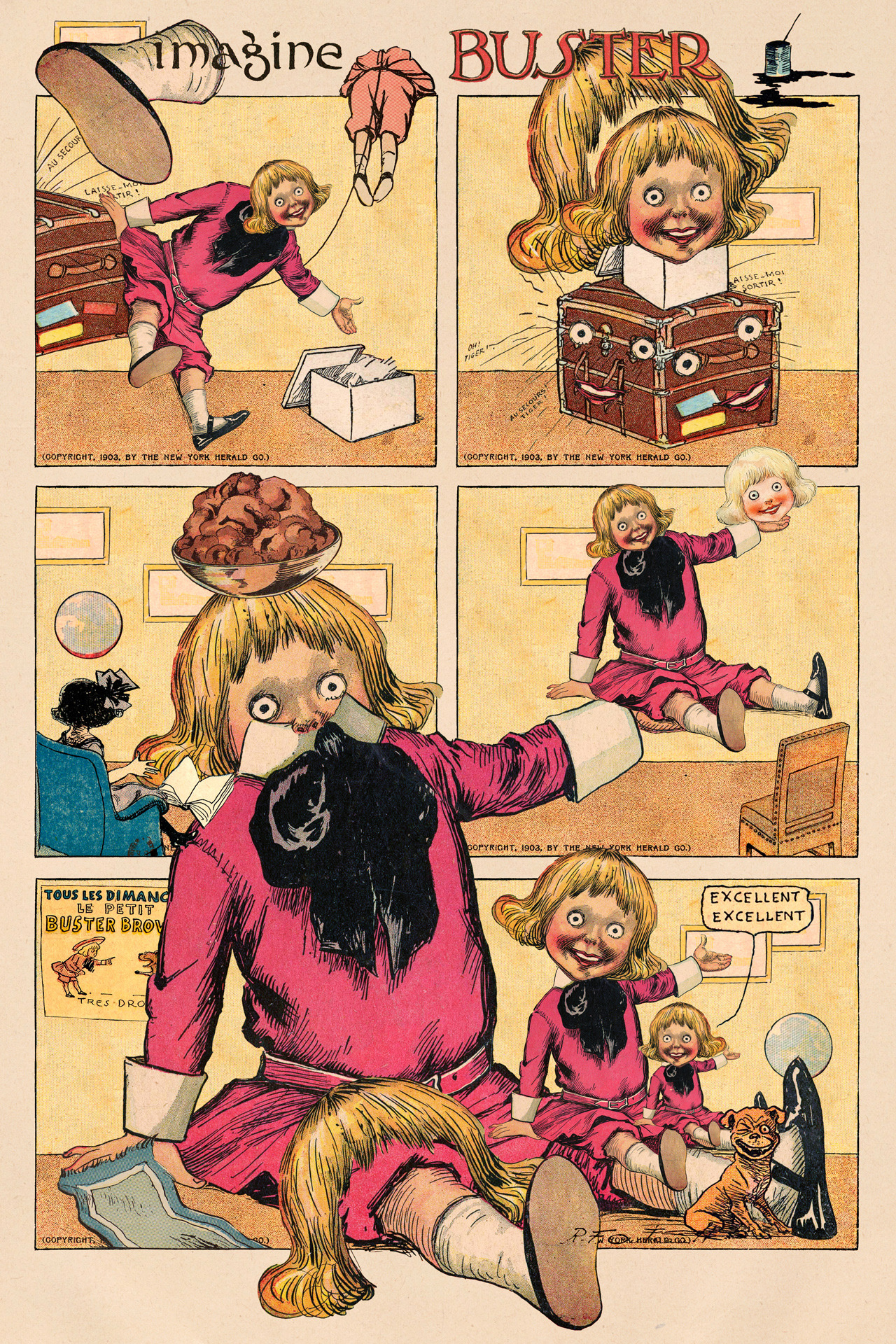

There’s the paranoia and alienation of adolescence Burns crafted in Black Hole, here delivered in a more vibrant, cohesive, and frankly wiser book. There’s the hallucinatory trauma and repression he conveyed in the X’ed Out trilogy (collected a decade ago as Last Look, the title of which prefigures Final Cut). There’s also an absence of parental authority here, a trope that Burns has deployed since 1991’s Curse of the Molemen. (In Final Cut, Brian’s mentally-unstable mother is a dead-ringer for Mrs. Pinkster, the domestic abuse victim rescued by the child-hero of Curse of the Molemen). There’s all the sinister dread and awful beauty that anyone following Burns’ career would expect, synthesized into his most lucid exploration of the inherent problems of artistic expression.

Ultimately, in Final Cut Charles Burns crafts a portrait of the artist as a weird young man. Brian wrestles with the friction sparked from his vital imagination butting up against cold reality. His ambitious unfinished film mirrors his own incomplete journey as an artist, highlighting the clash between youthful creative fervor and the inevitable constraints of life, experience, and maturity. Burns’ themes of alienation and artistic ambition may be familiar, but Final Cut feels fresh and vibrant, the culmination of the artist’s own entanglements with the irreality of reality. Highly recommended.

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel Final Cut tells the story of Brian, an obsessive would-be auteur grappling with an unrealized film project. Brian hopes to assemble his film — also titled Final Cut — from footage he shoots with friends on a weekend camping trip, but the messiness of reality impinges the weird glories of his vibrant imagination. He cannot bring his vision to the screen. He cannot capture all the “fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel Final Cut tells the story of Brian, an obsessive would-be auteur grappling with an unrealized film project. Brian hopes to assemble his film — also titled Final Cut — from footage he shoots with friends on a weekend camping trip, but the messiness of reality impinges the weird glories of his vibrant imagination. He cannot bring his vision to the screen. He cannot capture all the “fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”