Sugar Skull concludes the trilogy that Charles Burns began four years ago with X’ed Out (I reviewed it here) and its 2012 follow-up The Hive (I reviewed it here).

In X’ed Out, Burns introduces us to his protagonist Doug, a would-be art-punk poet whose Burroughsesque sound-collage performances are misunderstood by everyone but Sarah, a troubled artist whose photographs and installations reverberate with menacing violence. We first find Doug in the aftermath of an unnamed trauma involving Sarah and her tyrannical boyfriend—a trauma that Sugar Skull must and does answer to. The trauma transports Doug from his dead father’s office, where he’s been hiding and popping pills, into a fever-dreamscape reminiscent of William Burroughs’s Interzone. In this world, Doug becomes Nitnit, his own features transmuted to the Tintin mask he wears when performing his cut-ups.

The Hive takes Doug/Nitnit even deeper into Interzone, into its subterranean caverns, gaping like tumorous wombs, while simultaneously moving the “real” Doug forward and backward in time, through his doomed relationship with Sarah and into the fallout of their split, where Doug short circuits.

Sugar Skull completes this circuit, offering readers the complete picture—and an exit out of Interzone—even as it dooms Doug/Nitnit to repeat the past. We find here the traumatic violence of love, death, begetting, and denial.

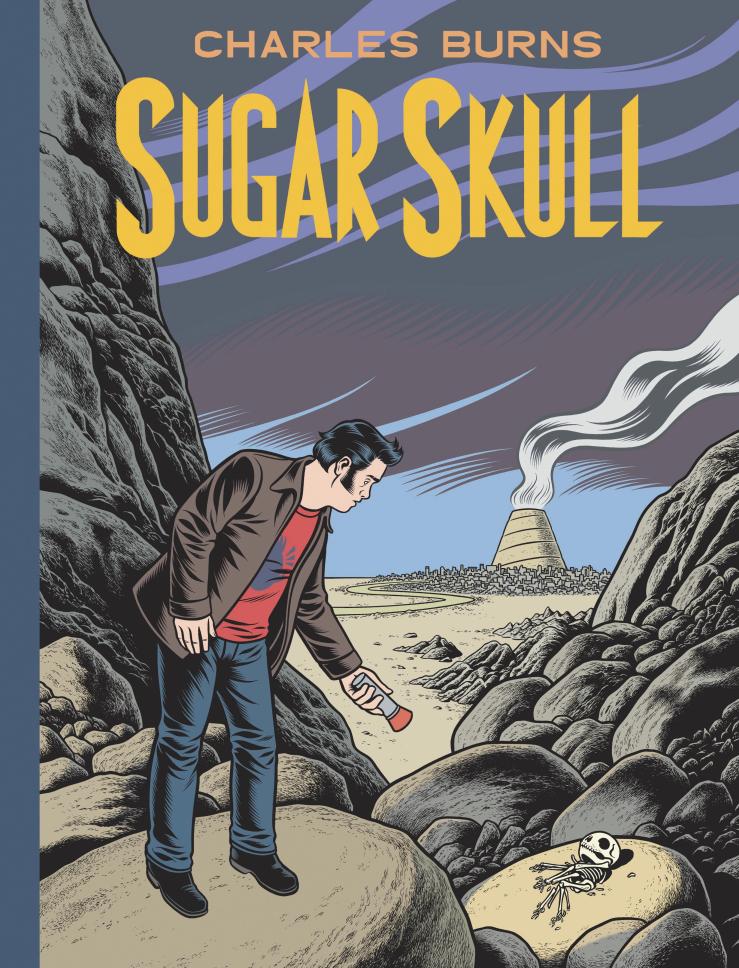

The trilogy’s development evinces in Burns’s rich cover art. X’ed Out shows us young, skinny Doug, his head bandaged, his haircut an echo of Tintin’s cowlick. Wrapped in his dead father’s purple robe and set against utter wreckage, young Doug regards a massive egg, itself a visual echo of a Tintin cover. The cover of The Hive shows us an older, heavier Doug, lost and confused in the abject uterine labyrinth of the Hive. In the lower-right corner—the same space the egg occupies on the cover of X’ed Out—lurks one of Interzone’s mutable mutants. This figure repeats in the trilogy, an amorphous being who shifts from Nitnit’s aide and familiar, to a dog stranded in a flood, to a piglet in a jar, to a massive breed-sow, to, perhaps, Doug’s father—and then Doug himself.

The figure opposite an older, fatter Doug on the cover of Sugar Skull condenses these roles into the emblem of death: it is at once the skeleton of the mutant, but also the frame of Doug’s dead father and the emblem of the symbolic infanticide at the core of the trilogy. And so we get the natural progression of life—from egg and embryo to a pink bundle of mobile cells to skeletal remains—set against an uncanny, chaotic backdrop.

Throughout the trilogy, Burns forces reader and Doug alike to navigate that chaos. The first two volumes in the series propelled the reader (and Doug, of course) through different times, different realities, sifting through the awful wreckage for clues, for a pattern, for an answer that might explain poor Doug’s trauma. By the beginning of Sugar Skull, our hero is finally equipped with a map to guide him through the underworld:

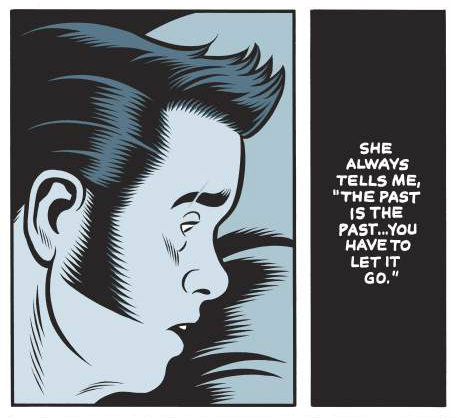

“Why does this have to be so difficult?” our hero wonders. Because of repressed fear, anger, hurt—and failure. The real trauma, the secret trauma, of the trilogy is Doug’s radical failure. This failure keeps him up at night, both in waking sweat, but also in his Interzone, the fantasy world where the repressed returns, where his alter-ego Nitnit can play boy detective. And yet, as we see in Sugar Skull, Nitnit, dream warrior, is ultimately unequipped to right the wrongs of the past. He can only replay them in a dark, surreal space. The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

“Why does this have to be so difficult?” our hero wonders. Because of repressed fear, anger, hurt—and failure. The real trauma, the secret trauma, of the trilogy is Doug’s radical failure. This failure keeps him up at night, both in waking sweat, but also in his Interzone, the fantasy world where the repressed returns, where his alter-ego Nitnit can play boy detective. And yet, as we see in Sugar Skull, Nitnit, dream warrior, is ultimately unequipped to right the wrongs of the past. He can only replay them in a dark, surreal space. The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

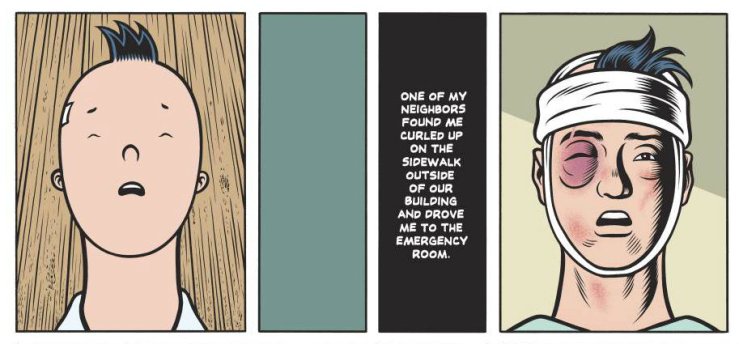

X’ed Out and The Hive point repeatedly to the specter of violence and infanticide, both through implication in the dialogue as well as intense imagery. Both novels ominously arrange events that could only lead to the head wound that our hero sustains before the trilogy begins—a head wound that may or may not be a primary cause of Doug’s excursions into irreality.

The infanticidal images that haunt the first two books pointed to a deeper mystery though, one beyond the physical violence Doug suffered. Those books hinted at abortion or miscarriage. But there are other ways to lose children.

Have I over shared the plot? Or am I hinting too vaguely? Reviewing my lines, it seems like I’ve said nothing at all, or perhaps dwelled on the first two books too much.

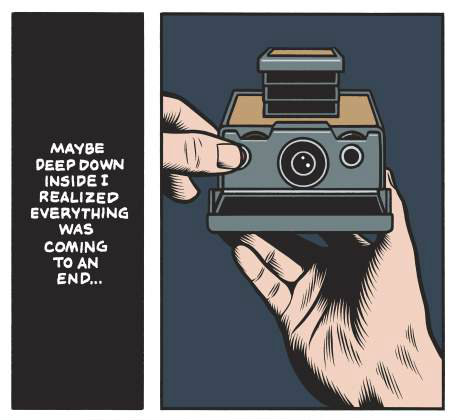

To simplify: Sugar Skull is sad and beautiful and strange and deeply human—this is not the tale of a doppelgänger’s adventures in wonderland, but rather the story of youth’s cowardice, of how we fail ourselves and others, how the versions of ourselves that we try to pin down—like Doug, who takes endless selfies with a Polaroid—are not nearly as stable as we might like them to be. Sugar Skull also explores how we cover over those instabilities and failures—I didn’t do those things; This isn’t happening to me.

The final moments of Sugar Skull enact a shock to stability, to sense of self. Burns fulfills a narrative promise to his readers, and to Doug—one that, if I’m honest, was not what I had predicted at all—and then sends Doug’s altered-ego Nitnit into the desert wilds. The last few pages of Sugar Skull seem to borrow as much from McCarthy’s Blood Meridian as they do from Hergés Tintin or William Burroughs.

And yet Doug passes through the wasteland to a refuge of sorts, the dream-double of two other settings that figure prominently in the trilogy, condensed into a place that is and is not. The setting mirrors Doug’s doomed double-consciousness, a consciousness condemned to repeat the same cycle, to respond again and again to the same terrifying call to nightmare-adventure.

I’ve neglected to comment on Burns’s wonderful art, mostly because I think it speaks for itself. His heavy inks and rich colors help unify the shift in styles that mark Doug’s movement between worlds. The trilogy would be worth the admission price alone just for the art, but Burns offers so much more with his storytelling. What’s perhaps most impressive is how thematically precise Burns’s images are—how panels, angles, shots, poses, gestures, and expressions repeat with difference from volume to volume. Burns uses these repeated images to subtly evoke his theme of cycles, doubles, and reiterations. In rereading we see again, recognize again—but from a different perspective.

And if Burns strands Doug/Nitnit in a loop of repetition, he also extends, perhaps, that same chance to his hero—to see again, but from a different perspective. If Sugar Skull forecloses the possibility of escape from the past, it doesn’t cut off a generative futurity. And as our protagonist awakes—again—to follow Inky into the strange wreckage of the past, many readers will feel prompted to follow the pair—again, and then again.

Sugar Skull is available now in hardback from Pantheon.

[…] Charles Burns via this isn’t happiness™ […]

LikeLike

This is an awesome review of a great book. I became interested in this new trilogy after first reading Black Hole. Your review makes a number of good observations about the story that some might otherwise miss, some of which I had also thought about. I also wrote reviews of the three books in the trilogy. My writing/analysis may not be as good, but I can send you the link if you want to check it out.

LikeLike

[…] Sugar Skull, Charles Burns […]

LikeLike