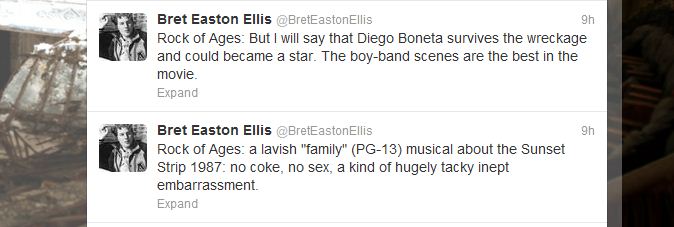

Late last night, Bret Easton Ellis took to Twitter to review the film Rock of Ages:

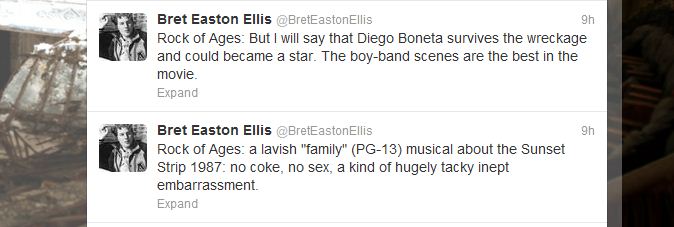

He then offered this bizarre nugget:

And here’s his evidence:

Late last night, Bret Easton Ellis took to Twitter to review the film Rock of Ages:

He then offered this bizarre nugget:

And here’s his evidence:

1984’s Dune is unquestionably the worst movie of Lynch’s career, and it’s pretty darn bad. In some ways it seems that Lynch was miscast as its director: Eraserhead had been one of those sell-your-own-plasma-to-buy-the-film-stock masterpieces, with a tiny and largely unpaid cast and crew. Dune, on the other hand, had one of the biggest budgets in Hollywood history, and its production staff was the size of a small Caribbean nation, and the movie involved lavish and cutting-edge special effects (half the fourteen-month shooting schedule was given over to miniatures and stop-action). Plus Herbert’s novel itself is incredibly long and complex, and so besides all the headaches of a major commercial production financed by men in Ray-Bans Lynch also had trouble making cinematic sense of the plot, which even in the novel is convoluted to the point of pain. In short, Dune’s direction called for a combination technician and administrator, and Lynch, though as good a technician as anyone in film, is more like the type of bright child you sometimes see who’s ingenious at structuring fantasies and gets totally immersed in them but will let other kids take part in them only if he retains complete imaginative control over the game and its rules and appurtenances—in short very definitely not an administrator.

Watching Dune again on video you can see that some of its defects are clearly Lynch’s responsibility, e.g. casting the nerdy and potato-faced Kyle MacLachlan as an epic hero and the Police’s resoundingly unthespian Sting as a psycho villain, or—worse—trying to provide plot exposition by having characters’ thoughts audibilized (w/ that slight thinking-out-loud reverb) on the soundtrack while the camera zooms in on the character making a thinking-face, a cheesy old device that Saturday Night Live had already been parodying for years when Dune came out. The overall result is a movie that’s funny while it’s trying to be deadly serious, which is as good a definition of a flop as there is, and Dune was indeed a huge, pretentious, incoherent flop. But a good part of the incoherence is the responsibility of De Laurentiis’s producers, who cut thousands of feet of film out of Lynch’s final print right before the movie’s release, apparently already smelling disaster and wanting to get the movie down to more like a normal theatrical running-time. Even on video, it’s not hard to see where a lot of these cuts were made; the movie looks gutted, unintentionally surreal.

In a strange way, though, Dune actually ended up being Lynch’s “big break” as a filmmaker. The version of Dune that finally appeared in the theaters was by all reliable reports heartbreaking for him, the kind of debacle that in myths about Innocent, Idealistic Artists In The Maw Of The Hollywood Process signals the violent end of the artist’s Innocence—seduced, overwhelmed, fucked over, left to take the public heat and the mogul’s wrath. The experience could easily have turned Lynch into an embittered hack (though probably a rich hack), doing f/x-intensive gorefests for commercial studios. Or it could have sent him scurrying to the safety of academe, making obscure plotless l6mm.’s for the pipe-and-beret crowd. The experience did neither. Lynch both hung in and, on some level, gave up. Dune convinced him of something that all the really interesting independent filmmakers—Campion, the Coens, Jarmusch, Jaglom—seem to steer by. “The experience taught me a valuable lesson,” he told an interviewer years later. “I learned I would rather not make a film than make one where I don’t have final cut.”

—From “David Lynch Keeps His Head” by David Foster Wallace; collected in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.

There’s a part in William Gaddis’s big novel The Recognitions where Basil Valentine talks about how forged paintings are always outed as fakes over time because they ultimately illustrate not the original genius of the artist, but instead show how the current zeitgeist interprets the artist. Film adaptations of books aren’t painted forgeries, but they are highly susceptible to the same critical limitations that Valentine discusses. We can see this plainly in Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 adaptation of Romeo & Juliet, a messy, vibrant, flaky film thoroughly shot-through with the aesthetic spirit of the nineties. I like Luhrmann’s R&J, despite its many, many faults. One of its great saving graces is that it seems aware of its own spectacle—it unselfconciously acknowledges itself as a product of its time, as just one of many, many adaptations of Shakespeare’s deathless work.

Lurhmann has taken a stab at F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. He’s not the first. Others attempted to turn Fitzgerald’s classic novel of the jazz age into a movie in 1926 (the film is lost), 1949 (there’s a reason you never saw it in high school), and 1974 (I’ll come back to the Redford Gatsby in a moment). Most recently, a 2000 anemic TV production featured Mira Sorvino as Daisy and Paul Rudd as a terribly miscast Nick Carraway. Up until now, high school teachers across the country who wanted to foist an adaptation on their students (and maybe free up a day or two of lesson planning) have had to choose between the 2000 A&E production or Jack Clayton’s 1974 Francis Ford Coppola-penned debacle—this is the one I was subjected to in high school. It features Robert Redford as Gatsby, Sam Waterston as Nick, and Mia Farrow as Daisy, and none of them are terrible, but the movie is dull, overly-reverential of its source material, and heavy-handed. It also looks incredibly dated now, its evocations of the 1920’s jazz age petrified in gauzy ’70s soft-focus shots. It just looks and feels very 1970s.

Judging by its trailer, Lurhmann’s Gatsby is making absolutely no play at all for timelessness. Just as his earlier mashup, 2001’s Moulin Rouge!, essentially uses the Belle Époque as a sounding board for transgenerational spectacle, Lurhmann’s Gatsby looks like another thoroughly interpretative gesture, a hyperkinetic, hyperstylized film that makes no bid at realism. This is what 2012 thinks 1922 should look like (or at least this is 2012’s ideal, shimmering, sexy version of 1922.) Here’s the trailer:

Overwrought, frenetic spectacle is exactly what I would expect from Luhrmann. There’s a transposition of meaning here, where Gatsby’s famous party turns into a rave of sorts, where Daisy’s phrasing of “You always look so cool” takes on anachronistic dimensions. But the trailer seems faithful (if hyperbolic) to images described in the book. By way of comparison, let’s look at the first shot in the trailer, the car full of young black people treating said car as a party scene. Here’s the text:

As we crossed Blackwell’s Island a limousine passed us, driven by a white chauffeur, in which sat three modish Negroes, two bucks and a girl. I laughed aloud as the yolks of their eyeballs rolled toward us in haughty rivalry.

“Anything can happen now that we’ve slid over this bridge,” I thought; “anything at all. . . .”

Even Gatsby could happen, without any particular wonder.

The energy of the scene is expressed—and magnified—in Luhrmann’s shot, but it’s impossible to say yet whether or not the invocation to change expressed in this citation will transfer to film.

It’s also obviously too early to make any pronouncements on the casting, although I’ll submit that you could find a worse Jay Gatsby than Leonardo DiCaprio (who I think, for the record, was great as petulant, whiny Romeo in Luhrmann’s breakthrough film). I’m not sure about Tobey Maguire as Nick Carraway, but there’s a certain, I don’t know, emptiness to him that may work well in our unreliable narrator. My big concern is Carey Mulligan, who I think is very sweet and I will admit to having a mild crush on—is she right for Daisy Buchanan, one of the meanest, most selfish creatures in literature? The other Buchanan, husband Tom, is portrayed by Joel Edgerton with a kind of seething rage here in the clip. Dude looks positively evil—cartoonishly so (which is really saying something, because Luhrmann seems to turn everything into a cartoon). Edgerton’s Tom presents as the glowering obstacle to the pure, positive love between Daisy and Gatsby. And here might be the biggest trip up with the film: The trailer seems to be advertising a love story.

Now, of course reading is an act of interpretation, a highly subjective experience dependent on any number of factors (see also: the opening paragraph to this riff). But good reading and good interpretation is generally supported by textual evidence, and the textual evidence in Gatsby reveals not so much a love story, but a bunch of nefarious creeps and awful liars who ruin the lives of the people around them with little thought or introspection. I mean, really, the principal characters are basically vile people (hence the reason your high school English teacher loved to point out Nick Carraway’s signature unreliability as a narrator—he glosses over so much evil). But again, it’s just a trailer, and trailers are made to make people buy tickets to movies, and people will pay to see a love story. We’ll have to wait for the film to assess Lurhmann’s interpretation. For now, it’s enough to suggest that the trailer achieved what it needed to—as of now, The Great Gatsby is still trending on Twitter. This is buzz; this is what a trailer is supposed to create. And if a byproduct of that buzz is to get more people reading or rereading, that can’t be a bad thing.

Let’s get this out of the way first:

I love W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn.

I think it’s an important book—but more than that I think it’s an engrossing, good, excellent book, an enlarging book, a bewildering book, a depressing book, an intelligent book, an extraordinarily affecting book.

I reviewed The Rings of Saturn and you can read that review if you feel the urge for me to support those claims in greater detail.

Better yet, read Sebald’s book.

Whatever you do, please don’t use Grant Gee’s new documentary Patience (After Sebald) as a substitution for actually reading Sebald. It’s not that Gee’s film doesn’t lovingly attempt to approximate the spirit of Saturn. No, Gee and his cast of writers, architects, historians, and other Sebaldians clearly attempt to match the rhythms and moods and content of Saturn—and herein lies the film’s failure.

In an essay on Virginia Woolf—a writer who shows up in both Sebald and in Patience—literary critic (and Sebald champion) James Wood notes the anxiety of influence always at work between the artistic subject and the would-be critic: “The competition is registered verbally. The writer-critic is always showing a little plumage to the writer under discussion.” Wood here is specifically calling attention to Woolf’s own critical powers—of her ability to transcend merely reviewing a work, of her status as a poet-critic—but I think he gives us a simple little rubric for evaluating critical work in general: the truly excellent stuff goes its own route. Gee’s film so dutifully commits to visually and aurally replicating the melancholy and erudite mood of Saturn that it often seems cartoonish or clumsy—or, even worse, dreadfully boring.

It’s not fair to put down one filmmaker for not being more like another, but I wish Gee had taken a page out of, say Errol Morris’s book. Morris’s style is, in a sense, to remove style, to eliminate the aesthetic shield between the subject and the camera/audience. In contrast, Patience is overstylized to an almost embarrassing degree. The film veers between lethargic, numbing black and white shots of the places that Sebald visited on his walking tour in Saturn, occasional archival footage, and slippery impositions of text, maps, documents, and talking heads—sometimes delivered in a bizarre, agitated pace. Perhaps the tone I’ve just described may seem appropriate to any critical measurement of Saturn; in my review of Sebald’s novel, I noted that one element of saturnine melancholy is “sluggishness and moroseness, paradoxically paired with an eagerness for action” — but Gee’s lack of restraint here is bad art school stuff. It’s as if he doesn’t trust the viewer to simply listen to (let alone watch) a talking head for a minute.

A few notes on those talking heads:

There are some very smart people here saying some really cool things about Sebald—writers like Rick Moody and Iain Sinclair, lit critic Barbara Hui (if you’re a Sebald fan you might’ve already seen her maps of his walks), some historians and architects and so on. There are also excerpts of Michael Silverblatt’s Bookworm interview with Sebald woven into the film, sometimes to great effect. Especially interesting are remarks from Christopher MacLehose, Sebald’s publisher, who recounts the time he asked the author which genre his book belonged to. Sebald replied, “Oh, I like all of the categories.”

Gee’s technique with his band of experts is to mostly cast their voices over cold landscape shots, occasionally superimposing a head for a few seconds in a ghostly mishmash that dissolves—along with the voice—into another shot or another voice. Sometimes this is really frustrating because, hey, maybe we’re missing some enlightening remarks, but more often than not it’s frustrating in its sloppiness. Film editing that constantly calls attention to itself is tiresome. The film is at its best when it it stops trying to honor/compete with Saturn and instead imparts some meaningful information about the man and his work. When Patience relaxes enough to simply show archival footage of RAF training flights, it’s a welcome moment from the film’s earnest, torpid buzz.

I realize “torpid buzz” is an oxymoron, but I think it fits Patience. In fact, it might be exactly what Gee was going for. There’s an oppressiveness about the film that belies the often gorgeous and expansive and empty shots of Suffolk, and yes, to be clear, there’s often a similar oppressiveness in Sebald’s book—an oppression of history, of self, of other—but this paradox does not translate well into film.

Sebald makes ample room for his reader; we get to go on this excursion with him. He lets us puzzle out his themes, connect all his strange dots (or not, if we so choose, or, perhaps just as likely, find ourselves unable). The gaps in clear meaning make Saturn such a strange, engrossing book, the kind of book that you return to again and again, the kind of book you press on others (I’ve given away two copies to date). In contrast to the breathing room that Sebald allows his readers, Patience feels somehow stifling and simultaneously small. There’s a brickishness to it, a forceful inclination to fill in all those marvelous Sebaldian gaps. And while yes, some of these people have some really keen insights about Sebald and Saturn, over the film’s interminable 80 minutes these opinions and insights and back stories start to torture meaning out of the text. Any potential reader has had much of her intellectual work removed at this point.

But perhaps I’ve been harsh without illustrating enough. Here’s psychoanalytic critic Adam Phillips who probably gets more voice time than anyone else in Patience; throughout the film he repeatedly over-explains Sebald’s project. I’ll shut up and let him talk (these are a few clips strung together, if my memory is sussing this out right):

Did you watch it? I watched it too—and it seems pretty cool at under four minutes, I’ll admit. But over the course of the film the heavy, “arty” edits, the overexplaining, well . . . it’s too much.

Admittedly, only ten minutes into the film I asked myself who the film was for. As a fan of the book I’d much prefer to just spend 80 minutes of my time rereading parts of it. Or, alternately, a straightforwardish biography would be nice too. And I suppose there are many, many people who will love what Gee’s done (the film has gotten plenty of rave reviews, including one by A.O. Scott at the Times). I also suppose many folks will commend Gee for trying out his own hybrid, for showing a little plumage. This is another way of saying that I think that Gee has turned in the film he intended to make—it just wasn’t for me.