Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Notes on Chapters 15-18 | Ghostly crawl.

Notes on Chapters 21-23 | Phantom gearbox.

Notes on Chapters 27-29 | We’re in for some dark ages, kid.

Notes on Chapters 30-32 | Some occult switchwork

Chapter 33 is the big-budget action sequence of Shadow Ticket, in which the “pocket-size golem Zdeněk” and musician/secret agent Hop Wingdale rescue Ace Lomax from the clutches of the fascist Vladboys in their “Hungaro-Croatian terrorist training camp, located right on the borderline.” (Notably–significantly–Hicks is missing from the rescue team.)

The narrator informs us that the camp is “flexibly all-purpose Fascist, quivering in readiness to be deployed anywhere…briefly innocent as Fascism in its ‘springtime of beauty,’ as the old anthem goes, before it descended into paperwork and brutality…” We tend to think, rightly, that fascism is a rejection of progressive values, but it’s worth remembering that much of what we now think of as Modernism was wrapped up in proto-fascist idealizations of energy and action — consider Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism f’r’instance…

The camp where Ace is being held prisoner is a hotbed of action:

“Fascist adventurers have journeyed here from all over, Austrians sporting blue cornflowers and black grouse feathers, secret police, anti-Red goon squads, revolutionary cells, convicts escaped from internal exile and not sure where they are right now or what language they’re supposed to be speaking, colonial stooges in civvies in from as far afield as Indo-China and South America, irredentist aristos from the old Hungarian kingdom adrift in nostalgia, Polish freelancers working on spec for all of the above.”

I love the force of the sentence. For such a breezy novel, Shadow Ticket is dense. We might take it as a sketch of a much larger, thicker, denser novel.

Well so and anyway–

The deal is that Hop’s band shows up to play this fascist gig; he’s informed that they, the fascist paramilitary Vladboys, “are pretending to invade Fiume, which any number of potential clients want back.” The garrulous entertainment liaison who meets with the band opines that such an invasion would be “all over in a day or two. Anasa supo.”

That last phrase, anasa supo, is Esperanto for duck soup, an American idiom referring to a task easily accomplished. Duck Soup is also of course the title of the 1933 Marx Brothers that centers (oh-so-anarchically) around the tiny nation of Freedonia–a bilocation of Fiume? Here’s a bit of bilocation from Duck Soup:

Hop and his band will play their swing tunes in “ruined limestone amphitheater, once dedicated to bloodletting presented as amusement, back when the Fifth Macedonian Legion were busy here invading and occupying.“

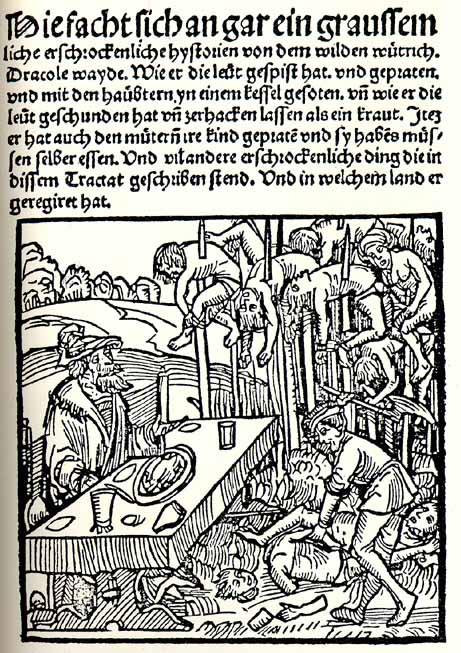

The entertainment menu is “A Gay Evening with Vlad Ţepeş,” with riffs including “Vlad’s Vegetarian Chef”…(“Turnip loaf again, remind me to have the chef impaled”) and “Vlad at the Office” (the Count laments that they never call him “Vlad the Spending Reducer.”)

Is this “Vlad Ţepeş” just a performer playing a character in the evening’s festivities, vamping on a riff–or is it, like, the Vlad Ţepeş, son of Vlad Dracul, Voivode of Wallachia, born half a century before the events of Shadow Ticket — like, Dracula man Vlad? A few paragraphs later, we are briefly introduced to the thug guarding Ace, “Csongor…a sort common in these parts, an apprentice vampire doomed never to develop past journeyman.” On one hand, the language here, and the general supernatural bent of Shadow Ticket suggests that these are like real (as in mythological) vampires — but the novel’s themes of bilocation also hedge the bet: vampire here could be a metaphor; the Vlad Ţepeş could be merely an actor playing a part.

Pynchon renders the scene in the kind of sexualized language we’d expect from vampire stories: “Vladboys have been building up, sending them out after prey each time in a more dangerous state of arousal. Trivial disputes are apt at any moment to erupt into violence. Local women go more and more in fear of their safety, cover their hair, stay in groups. The weirdly erotic charge accumulates, until vrrrooom! here’s the Vladboys out on another massive prowl…”

The prowl, as we’ve already learned, scores “Ace…an understandably welcome catch, with the Flathead an unexpected bonus, which the boys keep insisting is a Jewish motorcycle.” (The idiot vladboys reasoning? “Harley. David…Son, this is son of David, no?”)

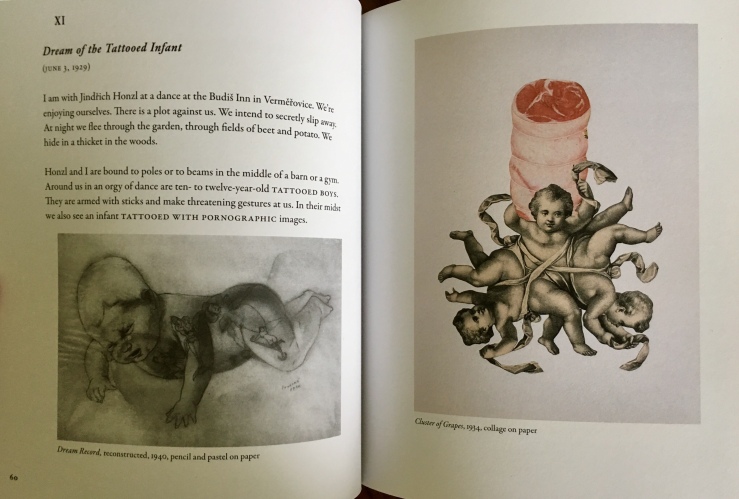

Standing guard over their “welcome catch,” journeyman vampire Csongor takes interest in Ace’s tattoo: “’Die Todten reiten schnell,’ the Vladboy reads from the Gothic lettering there. ‘Something about the dead ride fast.'”

The phrase “Denn die Todten reiten schnell” appears in the opening chapter of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a phrase recorded in Harker’s journal, which he identifies as the “line from [Gottfried August] Bürger’s ‘Lenore.'”

Csongor wants to know if the dead actually do ride fast. Ace’s answer is philosophical: “Over there, among the dead, time has no meaning anymore, so to get distance per hour you’d have to divide by zero, which even if it was legal would still give you infinite speed.”

But before he can really explain his riff on death-speed paradox though, Ace’s rescuers arrive: “the pocket-size golem Zdeněk [and] Hop Wingdale.” Our mini-golem is a cyborg: “Zdeněk’s left arm turns out to be a modified ZB-26 Czech light machine gun, with the magazine built into his shoulder.” He likens it to “one of many earthly variants of Azrael, the Angel of Death” — yet still spares Csongor.

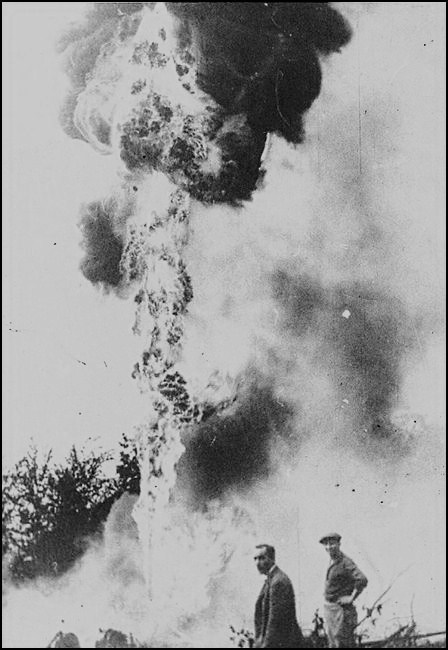

The chapter ends with our heroic trio escaping the fascist camp, fleeing their captors with the aid of a “pocket-size model” of a “a Bangalore torpedo” that Zdeněk has improvised from “a few sticks of dynamite thoughtfully borrowed last week in Transylvania off of a freelance firefighting crew passing through en route to a Romanian oil-well fire everybody could see from fifty miles away.”

The massive fire Pynchon’s narrator refers to here is, with most everything in Shadow Ticket, an historical event. The “torch of Moreni” burned for almost two and a half years, from September 1929 to November 1932.

Chapter 34 opens with a sentence that lays out the situation for us: “Daphne looking for Hop has blundered out into a territory she thought she knew, which in fact the political situation has changed to something unrecognizable and poisonous.”

The Weimar days are over; “Hamburg, once the Swing Kid metropol” is now a Nazi hotbed, where “Blues licks have largely given way to major triads.” Conformity reigns; difference is punished. Daphne finds this out the hard way when she “wanders into a beer garden [Hop’s band] the Klezmopolitans once played at, formerly named the Midnight Mouse after a poem by Christian Morgenstern, now converted to a Sturmlokal” — she’s stumbled into a Nazi bar, and immediately finds herself imperiled by the not-so-subtle sexual predations of fascist goons (“Looking for me, Schätzchen?”)

But before our “Cheez Princess…become[s] fondue” she’s by Glow Tripforth del Vasto in her autogyro-cum-deus-ex-machina. They alight to a tavern; on the way Glow complains that because gyros “are forgiving ships…there’s the danger [of] The idiot appeal…romance on the cheap.” Modern convenience will puncture Gothic adventures of flight. Any idiot can fly.

Glow, headed to “some kind of anarchist sainthood” in Spain, drops Daphne in Fiume, but first delivers another one of several hey-we’re-about-to-be-in-some-bigger-mess-than-we-thought-we-were-going-to-be-in proclamations: “Whatever it is that’s just about to happen, once it’s over we’ll say, oh well, it’s history, should have seen it coming, and right now it’s all I can do to get on with my life.”

Glow adds, “I don’t care to know more than I need to about the mysteries of time…You’re expecting spiritual wisdom from little G. T. del V.? you’ll be waiting a long time, sucker.”

The dead might ride fast–but they’re still dead.