Tao Lin has made the choice to be a very visible, very public author, one whose antics might lead audiences to form opinions on the 27 year old’s work before even reading it. I mention his age because he’s young, and not only is he young, he seems to be gunning to speak for his generation–always a precarious position.

Lin’s new novel Richard Yates is about young people. Specifically, it’s about a 22-year-old slacker named Haley Joel Osment and his 16-year-old girlfriend Dakota Fanning (I’ll address those names in a moment). Haley Joel Osment lives in Manhattan where he apparently is trying to make it as a writer–something that the book rarely delves into. Haley Joel Osment (Lin always writes the entire name out, part of the book’s numbing, trance-inducing program) meets fellow weirdo Dakota Fanning, and soon begins paying furtive visits to her New Jersey home, hiding in closets and under covers to avoid Dakota Fanning’s mother–who nevertheless soon discovers their illicit romance.

This is the primary conflict in the book–the age-of-consent gap between the young lovers–but the real trauma of the book lies in the couple’s urge toward self-annihilation. In conversations with each other–in person or in email, but primarily in Gmail chat–Haley Joel Osment and Dakota Fanning frequently promise to kill themselves, usually in a casual, detached tone. If “I will probably kill myself later this week” is one of their mantras, the other is “I’m fucked” or “We’re so fucked.” These are not happy people. Here’s Haley Joel Osment writing an email to Dakota Fanning, summarizing his philosophical position: “At each moment you can either kill yourself, try harder to detach yourself from people and reality, or be thinking of and doing what you can for the people you like.”

The bulk of the book consists of such conversations, mopey or mordant or mean. Haley Joel Osment accuses Dakota Fanning of being the type of person who wants to detach from others and reality, yet he’s just as guilty. Lin allows the audience into Haley Joel Osment’s interior, where we find a deeply troubled young man, alienated by his own inability to stop over-processing everything he sees. The problem is that Haley Joel Osment is the core referent of all of Haley Joel Osment’s observations; his solipsism prevents him from actually really knowing anyone else. Mulling over Dakota Fanning’s minutest movements, he repeatedly reads in them signs about her own regard for him. Even when he attempts to be the type of person who is “thinking of and doing what [he] can for the people” he likes, he’s not. He’s selfish and cannot see his own selfishness. The kernel of self-destruction at the heart of Haley Joel Osment and Dakota Fanning’s relationship doesn’t emerge from their age difference but rather his slow, cruel manipulation of her self-image. As the book progresses, Haley Joel Osment’s “advice” cripples Dakota Fanning, leading her down a path of bulimia and self-mutilation.

Lin’s style is flat, dry, and utterly concrete. The only metaphors or similes he employs come (quite artlessly) from his characters. Furthermore, these figures of speech seem incidental; even the couple’s code word “cheese beast” feels like a metaphor with no referent (or perhaps too many referents). There are no symbols (or perhaps the book is all symbols). In many ways, Richard Yates recalls Bret Easton Ellis’s early work, although Lin’s observations and comments on twenty-first century materialism are even more oblique and ambiguous than the moralism of Less Than Zero. The most immediate rhetorical technique, of course, is the book’s title. Although the text refers to the writer Richard Yates several times, his name seems utterly arbitrary, perhaps an obscure joke meant to purposefully confuse. And those character names. For the first few pages, Lin’s choice to name his protagonists after famous child stars seems gimmicky or overdetermined, but in time these names displace their original referents, as well as any other associations. They become like placeholders; Lin might as well have named them X and Y. As if to flatten out his characters even more, Lin also transliterates all of their speech. Much of the novel takes place in conversations over Gmail chat, email, and text messages, but Lin turns these truncated forms into full, affectless sentences. He even removes most contractions. His characters often speak like androids, albeit androids prone to spouting non sequiturs.

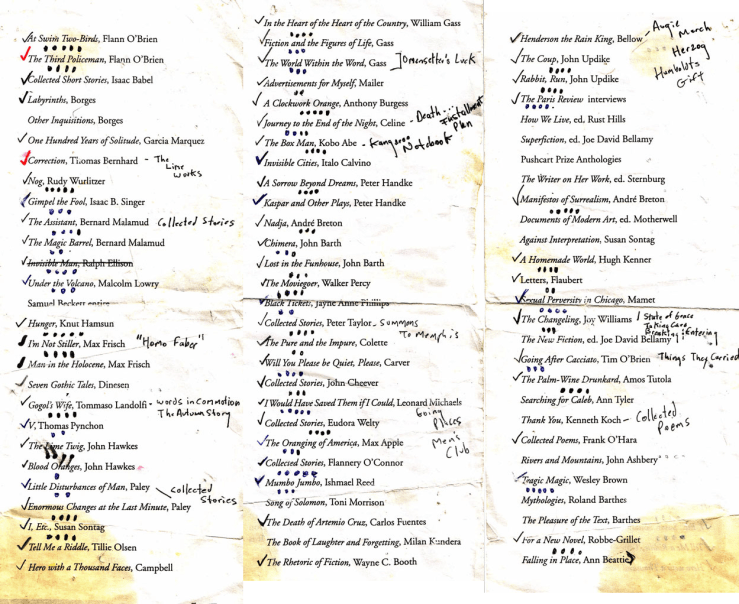

Lin also makes the odd decision to include an index to the book, part of which you can see above. In a sense, reading the index is like reading a condensed version of the book. It’s a lump sum of nouns that the book treats with more or less equal weight. The long list under the entry “facial expression” perhaps reveals the most about the book’s program, about its refusal to yield insights or give away anything beyond surfaces–it reads almost like a cheat sheet for someone with Asperger syndrome. The index seems like a postmodern gesture but it’s something else–I’m not sure exactly what else–but there’s nothing sly or even self-referential about it: it’s literal, it’s surface, it’s referential. In turn, Lin resists commenting on or satirizing the sundry brand names and corporate locations that populate his index (and, of course, his novel)–a marked contrast to the postmodern tradition.

This is all perhaps a way of saying that Lin is clearly attempting something new with his fiction, a kind of writing that abandons most conceits of post-modern cleverness and self-commentary, yet also compartmentalizes the pathos that characterizes social realist novels. This latter comparison might seem odd unless one considers the concreteness of social realist works, their emphasis on the body, on food, on places. Richard Yates shares all of these emphases, yet it divorces them from ideology; or, more accurately perhaps, it documents an as-yet-unnamed ideology, a 21st century power at work on body and soul. If Lin’s goal then is to document these forces, he succeeds admirably–but I want more; more soul, more insight, more, yes, abstraction. Richard Yates gives us the who and the what, replicates the when and where with uncanny ease; it even tells us how. But many readers, like me, will want to know the why, even if it is just a guess. And I’d love to hear Lin’s guess.

Richard Yates is new this week from Melville House.

(

(

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The