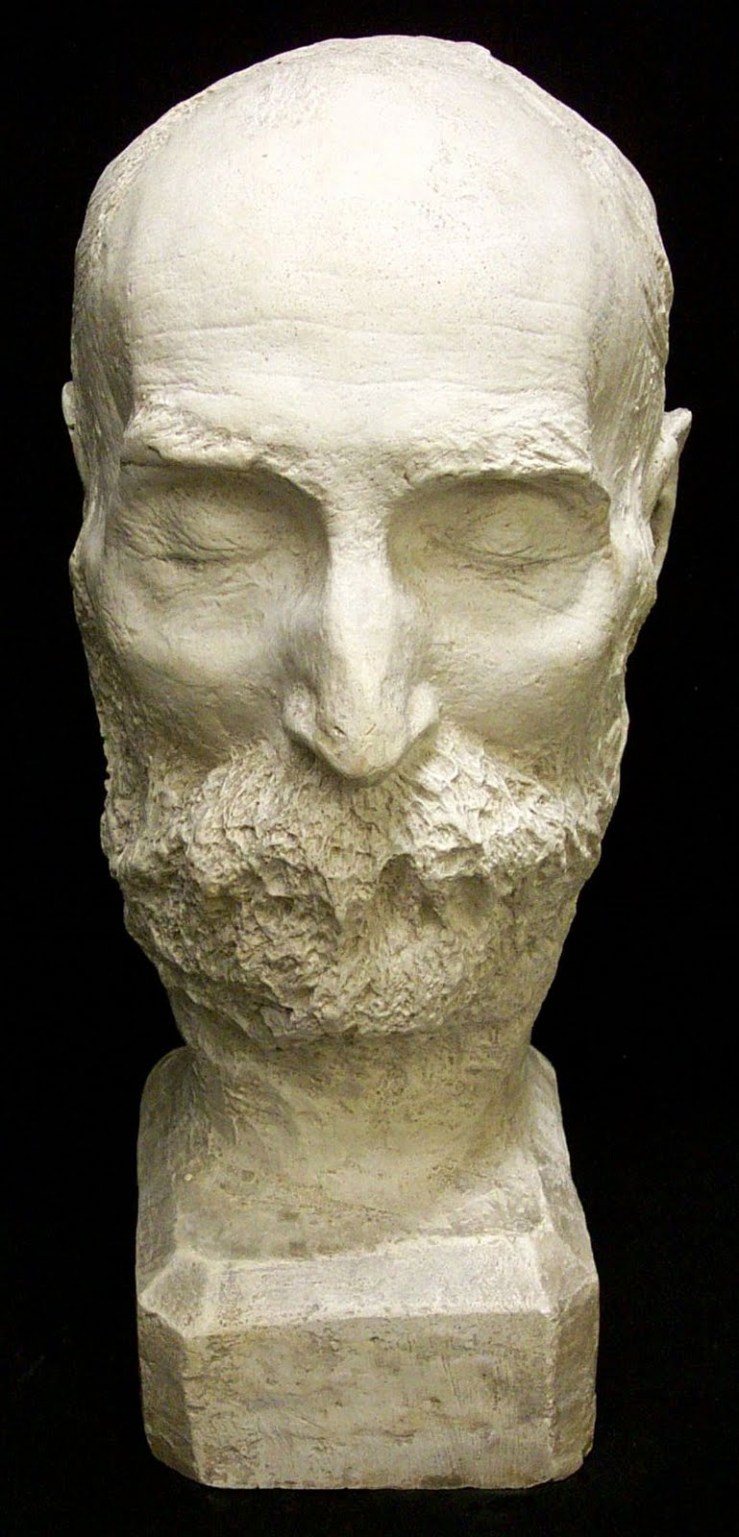

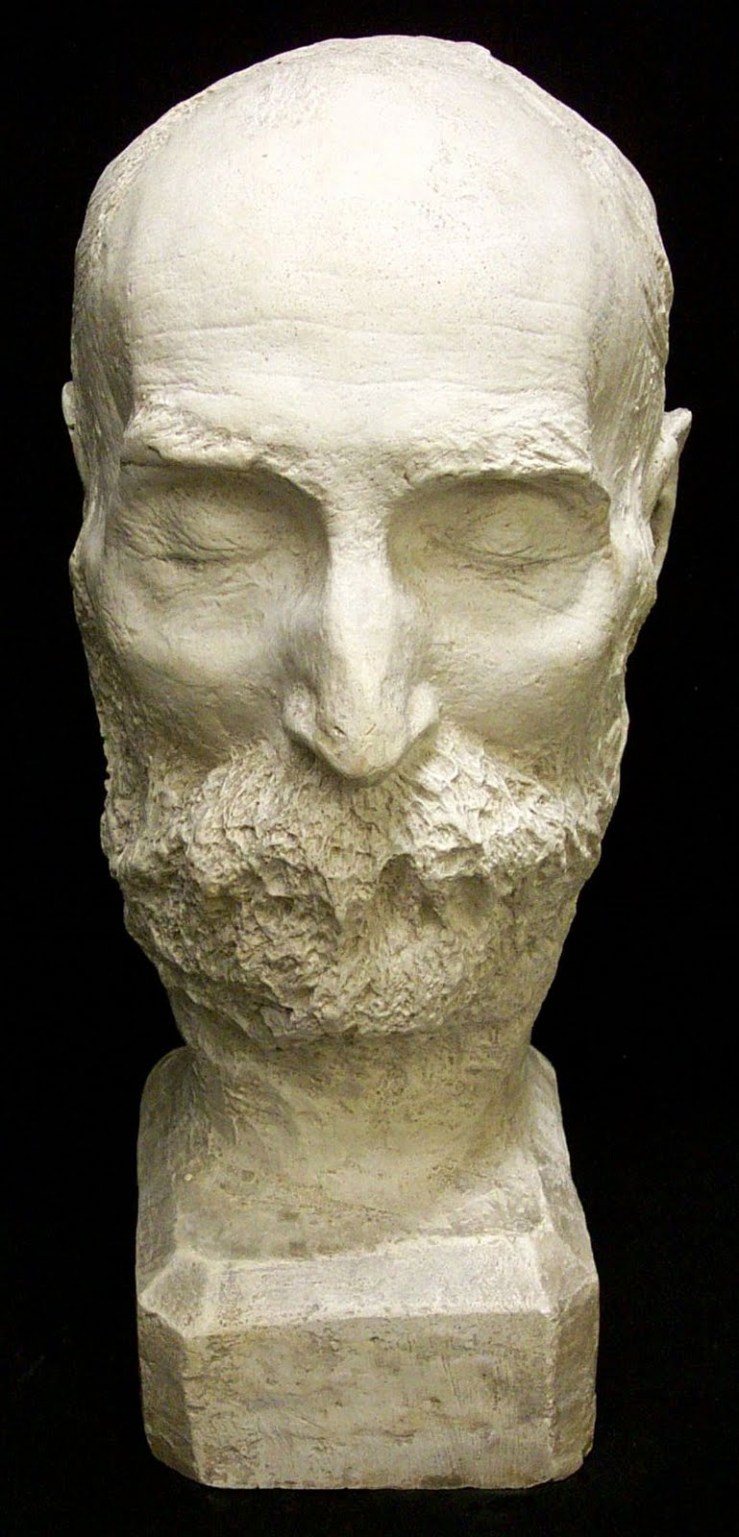

Read more about Walt Whitman’s death mask here. Read Whitman’s poem “Starting from Paumonak,” where he claims “I will show that nothing can happen more beautiful than death.”

Read more about Walt Whitman’s death mask here. Read Whitman’s poem “Starting from Paumonak,” where he claims “I will show that nothing can happen more beautiful than death.”

More Intelligent Life interviews Tom McCarthy about his new novel C. From the interview–

MIL: It seems many avant-garde works rely on a single conceit. “Tristam Shandy” used lies, “Motherless Brooklyn” used a tourettic narrator. Must avant-garde literature have a single mechanism to be intelligible to its readers?

TM: What’s the conceit of “Finnegans Wake” then? I’m not sure “Tristram Shandy” has a single conceit. I suppose there’s an inversion of the ‘Life and Adventures of’ tradition into ‘The Life and Opinions of—plus an obvious refusal of certain narrative conventions, for example in Tristram’s inability to get himself born for the first third of his own book. But Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” is equally full of such refusals: it subverts just about every dramatic convention that it purports to buy into. I’m suspicious of the term ‘avant-garde’. I think it should be restricted to its strict historical designation: Futurists, Dadaists, Surrealists etc. “Tristram Shandy” and “Motherless Brooklyn” aren’t avant-garde novels; they’re novels. And very good ones too!

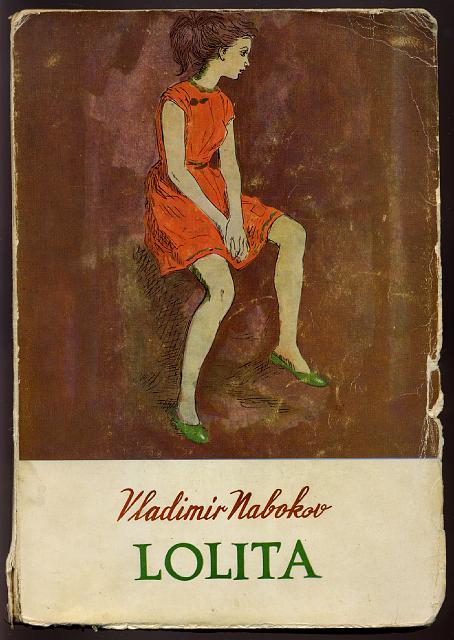

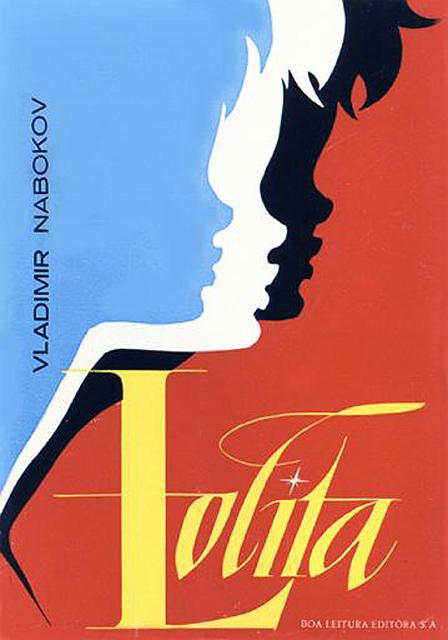

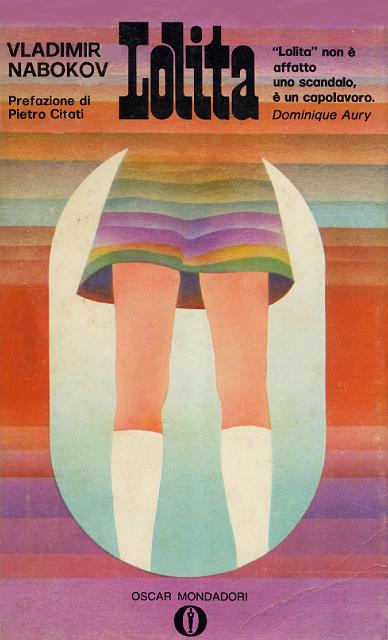

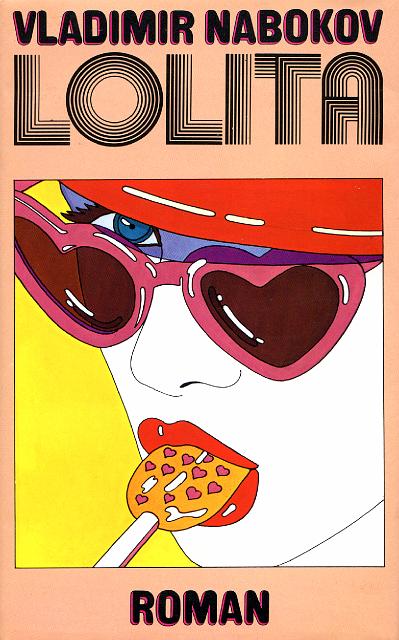

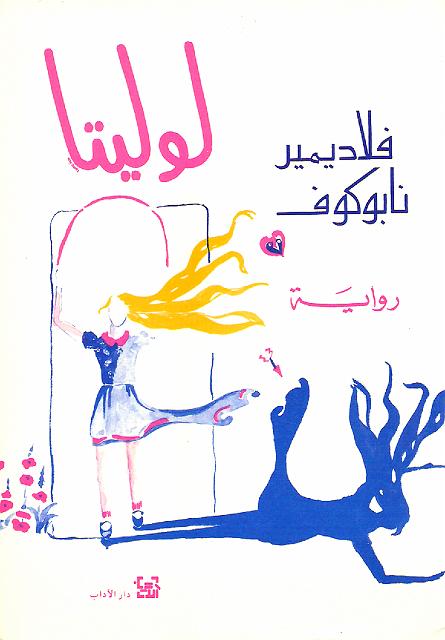

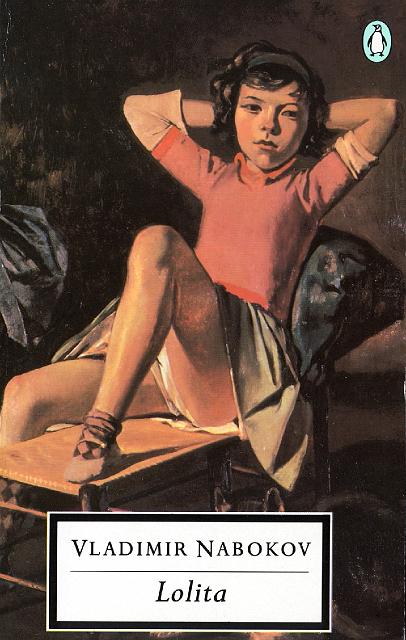

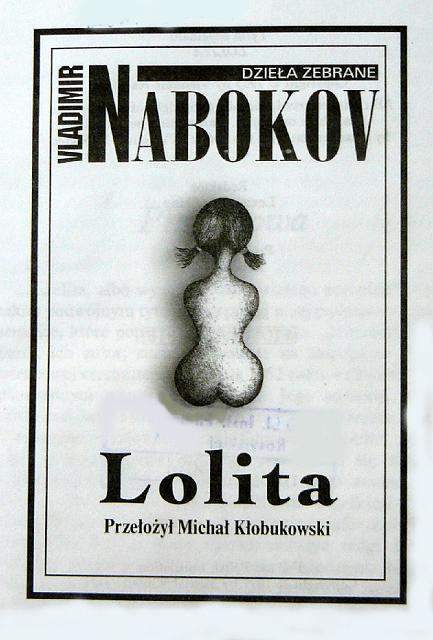

Checkout this great cover gallery archiving over 150 covers of Vladimir Nabokov’s masterpiece Lolita. A few favorites–

This 1957 Swedish cover is a pretty subtle/creepy upskirt.

1962, Brazil.

1962, Brazil.

A 1964 LP with Pop Art undertones–seems a little too frank.

This 1970 Italian cover seems to be the earliest “girl in socks” theme that pops up again and again in the archive.

This 1972 Norwegian cover picks up the voyeur theme again, but it seems awfully goofy.

The poster for the Stanley Kubrick film adaptation inspired a rash of bad covers, but I think that this 1977 German cover works really well.

A Lebanese edition from 1988. Pretty and simple.

Balthus and Lolita seem like a natural fit, if a bit too obvious. I counted two other covers sporting Balthus paintings in addition to this 1995 English edition.

This Polish cover from 1997 is nine kinds of creepy.

Tin House #45, out in September, focuses on “Class in America.” You can read Gerald Howard’s essay from that issue, “Never Give an Inch,” in full now. The essay discusses shifting ideas of the social class of the American novelist, with an emphasis on “working class” writers. Howard discusses Raymond Carver and Russell Banks at some length, as well as Richard Price and Dorothy Allison (he also mentions Gilbert Sorrentino, whose work seems to be enjoying a late reappraisal). From the essay–

I don’t suppose anyone has ever done an in-depth study of that interesting form of literary ephemera, the author dust jacket biography. But if they did, I’m sure they would notice a distinct sociological shift over the past decades. Back in the forties and fifties, the bios, for novelists at least, leaned very heavily on the tough and colorful professions and pursuits that the author had had experience in before taking to the typewriter. Popular jobs, as I recall, were circus roustabout, oil field roughneck, engine wiper, short-order cook, fire lookout, railroad brakeman, cowpuncher, gold prospector, crop duster, and long-haul trucker. Military experiences in America’s recent wars, preferably combat-related, were also often mentioned. The message being conveyed was that the guy (and they were, of course, guys) who had written the book in your hand had really been around the block and seen the rougher side of life, so you could look forward to vivid reading that delivered the authentic experiential goods.

It’s been a long time since an author has been identified as a one-time circus roustabout. These days such occupations have become so exotic to the average desk-bound American that they serve as fodder for cable television reality shows—viz., The Deadliest Catch, Dirty Jobs, and Ice Road Truckers. Contemporary dust jacket biographies tend to document the author’s long march through the elite institutions, garnering undergraduate and postgraduate and MFA degrees, with various prizes and publications in prestigious literary magazines all duly noted. Vocational experiences generally get mentioned only when pertinent to the subject of the novel at hand—e.g., assistant DA or clerk for a Federal judge if the book deals with crime or the intricacies of the law. Work—especially the sort of work that gets your hands dirty and that brands you as a member of the working class—no longer seems germane to our novelists’ apprenticeships and, not coincidentally, is no longer easy to find in the fiction they produce. Whether one finds this scarcity something to worry about or simply a fact to be noted probably says a lot about one’s class origins and prejudices.

The Rumpus interviews David Mitchell. Topics include his brilliant new novel The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, diction, syntax, and other writerly concerns. And stammering. I’m currently finishing up Mitchell’s novel Black Swan Green, which is hilarious and sad and beautiful. I will review it here shortly.

The Guardian reports that the detainees/living Kafka characters at Guantánamo Bay can’t get enough Dan Brown, John Grisham, Agatha Christie, and J.K. Rowling.

Best paragraph:

Civil rights lawyer H Candace Gorman sent the library an Arabic edition of a Harry Potter book herself because it did not have all of the published titles and her client, the Libyan national Abdul al-Ghizzawi, was keen to keep up with the boy wizard’s adventures. “The guards were telling him things that had happened in the book, but he didn’t know if it was true or not,” she told Time. Ghizzawi saw similarities between his own situation and that of the prisoners of Azkaban, and between George W Bush and Voldemort, she said.

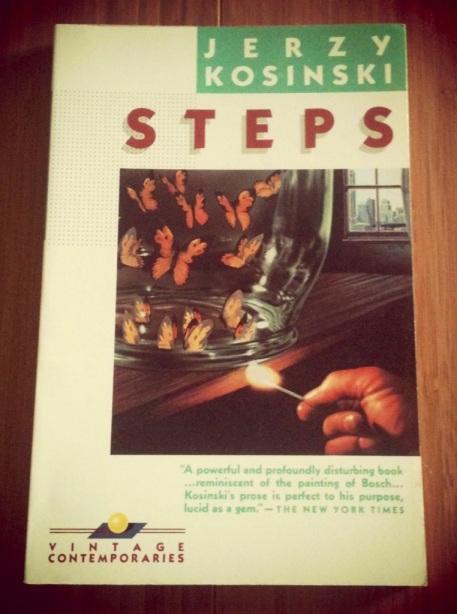

One of the many small vignettes that comprise Jerzy Kosinski’s 1968 book Steps begins with the narrator going to a zoo to see an octopus that is slowly killing itself by consuming its own tentacles. The piece ends with the same narrator discovering that a woman he’s picked up off the street is actually a man. In between, he experiences sexual frustration with a rich married woman. The piece is less than three pages long.

There’s force and vitality and horror in Steps, all compressed into lucid, compact little scenes. In terms of plot, some scenes connect to others, while most don’t. The book is unified by its themes of repression and alienation, its economy of rhythm, and, most especially, the consistent tone of its narrator. In the end, it doesn’t matter if it’s the same man relating all of these strange experiences because the way he relates them links them and enlarges them. At a remove, Steps is probably about a Polish man’s difficulties under the harsh Soviet regime at home played against his experiences as a new immigrant to the United States and its bizarre codes of capitalism. But this summary is pale against the sinister light of Kosinski’s prose. Consider the vignette at the top of the review, which begins with an autophagous octopus and ends with a transvestite. In the world of Steps, these are not wacky or even grotesque details, trotted out for ironic bemusement; no, they’re grim bits of sadness and horror. At the outset of another vignette, a man is pinned down while his girlfriend is gang-raped. In time he begins to resent her, and then to treat her as an object–literally–forcing other objects upon her. The vignette ends at a drunken party with the girlfriend carried away by a half dozen party guests who will likely ravage her. The narrator simply leaves. Another scene illuminates the mind of an architect who designed concentration camps. “Rats have to be removed,” one speaker says to another. “Rats aren’t murdered–we get rid of them; or, to use a better word, they are eliminated; this act of elimination is empty of all meaning. There’s no ritual in it, no symbolism. That’s why in the concentration camps my friend designed, the victim never remained individuals; they became as identical as rats. They existed only to be killed.” In another vignette, a man discovers a woman locked in a metal cage inside a barn. He alerts the authorities, but only after a sinister thought — “It occurred to me that we were alone in the barn and that she was totally defenseless. . . . I thought there was something very tempting in this situation, where one could become completely oneself with another human being.” But the woman in the cage is insane; she can’t acknowledge the absolute identification that the narrator desires. These scenes of violence, control, power, and alienation repeat throughout Steps, all underpinned by the narrator’s extreme wish to connect and communicate with another. Even when he’s asphyxiating butterflies or throwing bottles at an old man, he wishes for some attainment of beauty, some conjunction of human understanding–even if its coded in fear and pain.

In his New York Times review of Steps, Hugh Kenner rightly compared it to Céline and Kafka. It’s not just the isolation and anxiety, but also the concrete prose, the lucidity of narrative, the cohesion of what should be utterly surreal into grim reality. And there’s the humor too–shocking at times, usually mean, proof of humanity, but also at the expense of humanity. David Foster Wallace also compared Steps to Kafka in his semi-famous write-up for Salon, “Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels > 1960.” Here’s Wallace: “Steps gets called a novel but it is really a collection of unbelievably creepy little allegorical tableaux done in a terse elegant voice that’s like nothing else anywhere ever. Only Kafka’s fragments get anywhere close to where Kosinski goes in this book, which is better than everything else he ever did combined.” Where Kosinski goes in this book, of course, is not for everyone. There’s no obvious moral or aesthetic instruction here; no conventional plot; no character arcs to behold–not even character names, for that matter. Even the rewards of Steps are likely to be couched in what we generally regard as negative language: the book is disturbing, upsetting, shocking. But isn’t that why we read? To be moved, to have our patterns disrupted–fried even? Steps goes to places that many will not wish to venture, but that’s their loss. Very highly recommended.

Proving that he’s the kind of elitist Harvard-educated snob who reads literature, President Barack Obama picked up an advance copy of Jonathan Franzen’s forthcoming novel Freedom today. Obama also picked up copies of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird and John Steinbeck’s The Red Pony for daughters Sasha and Malia (spoilers for S & M, undoubtedly faithful Biblioklept readers both: Boo Radley isn’t so bad, that white dude raped his daughters, and they have to kill the pony’s mama. But not all in the same book). Also, our president is photographed outside the bookstore wearing what appears to be socks and sandals. (Okay, looked like socks and sandals in the light. But we’ll give BO the benefit of the doubt).

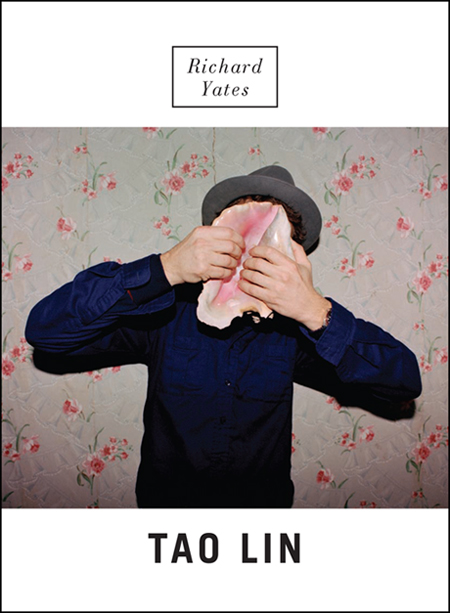

“Tao Lin Will Have the Scallops” by Christian Lorentzen. I’m about halfway through Lin’s forthcoming novel, Richard Yates, which is somehow both far out and totally banal at the same time. Its cover is pretty awesome–

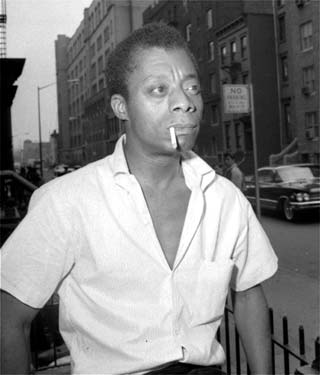

NPR’s Morning Edition featured James Baldwin today as part of their continuing “American Lives” series. Listen and read here. Their lede–

The writer James Baldwin once made a scathing comment about his fellow Americans: “It is astonishing that in a country so devoted to the individual, so many people should be afraid to speak.”

As an openly gay, African-American writer living through the battle for civil rights, Baldwin had reason to be afraid — and yet, he wasn’t. A television interviewer once asked Baldwin to describe the challenges he faced starting his career as “a black, impoverished homosexual,” to which Baldwin laughed and replied: “I thought I’d hit the jackpot.”

In the piece, NPR talks with Randall Kenan, editor of a new collection of Baldwin’s essays, speeches, and articles called The Cross of Redemption. The link above includes a great excerpt of one of Baldwin’s essays, “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare.” A taste–

The greatest poet in the English language found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people. He could have done this only through love — by knowing, which is not the same thing as understanding, that whatever was happening to anyone was happening to him. It is said that his time was easier than ours, but I doubt it — no time can be easy if one is living through it. I think it is simply that he walked his streets and saw them, and tried not to lie about what he saw: his public streets and his private streets, which are always so mysteriously and inexorably connected; but he trusted that connection. And, though I, and many of us, have bitterly bewailed (and will again) the lot of an American writer — to be part of a people who have ears to hear and hear not, who have eyes to see and see not — I am sure that Shakespeare did the same. Only, he saw, as I think we must, that the people who produce the poet are not responsible to him: he is responsible to them.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden, Helen Grant’s debut novel, negotiates the razor’s edge between childhood’s rich fantasy world and the grim reality of adult life. When young girls start disappearing in her small German village, eleven year old protagonist Pia sets out to investigate, armed with her powers of imagination–an imagination fueled by the Grimmish tales spun by her elderly friend Herr Schiller for the pleasure of Pia and her only friend, StinkStefan. Like poor Stefan, Pia is ostracized by the town after her grandmother spontaneously combusts on Christmas. She takes to playing detective, but as she investigates the girls’ disappearances, the illusions of her fantasy life cannot protect her. As the story builds to its sinister climax, it reminds us that most of the folktales we grew up with are far darker than we tend to remember.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden, Helen Grant’s debut novel, negotiates the razor’s edge between childhood’s rich fantasy world and the grim reality of adult life. When young girls start disappearing in her small German village, eleven year old protagonist Pia sets out to investigate, armed with her powers of imagination–an imagination fueled by the Grimmish tales spun by her elderly friend Herr Schiller for the pleasure of Pia and her only friend, StinkStefan. Like poor Stefan, Pia is ostracized by the town after her grandmother spontaneously combusts on Christmas. She takes to playing detective, but as she investigates the girls’ disappearances, the illusions of her fantasy life cannot protect her. As the story builds to its sinister climax, it reminds us that most of the folktales we grew up with are far darker than we tend to remember.

The Vanishing of Katharina Linden makes its American debut this month from Delacorte Press.

Diego Trelles Paz remembers Roberto Bolaño at n +1. Although Paz never met the author (despite several attempts) they corresponded, and he shares some of the emails. Here’s Paz on The Savage Detectives—

What did I like about Bolaño’s novel?

In formal terms, it was clear to me that his prose, while apparently simple, has a restrained and suggestive lyricism and a powerful musicality that are very different than what the authors of the “Boom” produced. Reading Bolaño generated an instant addiction in me: whether due to the lucid and demystifying spirit with which he adopts diverse genres or to his eagerness to involve us as active readers, to offer us fragmented works so we might fill them in with our imaginations. We become accomplices who search for truth through narrative devices that blend reality with fiction, facts with conjectures, apocryphal characters with historical ones. As the critic José Miguel Oviedo has said, “Bolaño always ends up turning his readers into detectives.”

The article also features this marvelous image of Bolaño enjoying an ice cream cone–

The Guardian has published David Mitchell’s short story “Muggins Here” as part of its summer fiction special (other authors include Hilary Mantel and Roddy Doyle). Here’s an excerpt–

A proper mental Saturday it is, what with New Sue off with her hernia and the Lukes of Hazzard gone AWOL, so Muggins Here’ll have to cover for everyone else’s break. Not New Sue and Beverly are still giving me the silent treatment ’cause I can’t let them take the bank holiday off, but it’s water off a duck’s back by this point. By ten o’clock the queues are looping back, and it’s like all Greenland’s one of those swilling dreams you get with ‘flu. Full of eyes, drilling into me. Philpotts can’t get close enough to fire off a “What are half your team doing without their name-badges, Pearl?” but I need the loo – no chance, not ’til all the breaks are over. This beardy customer’s spitting, “Twenty-three minutes I’ve been in this queue!” I tell him, “It certainly is a busy morning” so in he leans, breath all pilchardy, and says, “Then hire – more – staff!”, like I’m backwards, like Gary used to do sometimes. I ask for his “I Love Greenland” Loyalty Card and while he’s fishing through his wallet I’m working out that I’ve still got three hundred and forty minutes ’til I can go home. Last week I turned forty-five so that’s nineteen years ’til I retire, though now they’re reckoning we’ll have to work ’til seventy. Seventy! Doesn’t bear thinking about, does it? I really really need the loo. When I ask the man, “Cash back?” he gives me this withering, “That’s exactly what landed the economy in the crappers in the first place” and then, “What’s so green about Greenland Supermarkets dishing out fifty plastic bags to every customer?”

Time profiles Jonathan Franzen this week (part of the push for his new novel Freedom, out later this month). Franzen also talks about five works that have “inspired him recently.” Here are his comments on those books–

Time profiles Jonathan Franzen this week (part of the push for his new novel Freedom, out later this month). Franzen also talks about five works that have “inspired him recently.” Here are his comments on those books–

The Charterhouse of Parma by Stendhal

Instead of sitting for years at his writing desk, pulling his hair, Stendhal served with the French diplomatic corps in his favorite country, Italy, and then came home and dictated his novel in less than eight weeks: what a great model for how to be a writer and still have some kind of life! The book is at once deeply cynical and hopelessly romantic, all about politics but also all about love, and just about impossible to put down.

The Greenlanders by Jane Smiley

There’s nothing fancy about the writing in Smiley’s masterpiece, and yet every sentence of its eight hundred pages is clean and necessary. For the two weeks it took me to read it, I didn’t want to be anywhere else but in late-medieval Greenland, following the passions and feuds and farming crises of European settlers trying to survive in the face of ecological doom. It all felt weirdly and plausibly contemporary.

Sabbath’s Theater by Philip RothI finally got tired of being angry at Roth for his self-indulgent excesses and weak dialogue and thin female characters and decided to open myself to his genius for invention and his heroic lack of shame. Whole chunks of Sabbath’s Theater can be safely skipped, but the great stuff is truly great: the scene in which Mickey Sabbath panhandles on the New York with a paper coffee cup, for example, or the scene in which Sabbath’s best friend catches him relaxing in the bathtub and fondling his (the friend’s) young daughter’s underpants.

The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

Wharton’s male characters suffer from some of the deficiencies that Roth’s female characters do, but the heroine of House of Mirth, Lily Bart, is one of the great characters in American literature, a pretty and smart but impecunious New York society woman who can’t quite pull the trigger on marrying for money. Wharton’s love for Lily is equal to the cruelty that Wharton’s story relentlessly inflicts on her; and so we recognize our entire selves in her.

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

A lifelong heavy drinker with his most famous novel well behind him, Steinbeck set out to write a mythic version of his family’s American experience that would embody the whole story of our country’s lost innocence and possible redemption. There are infelicities on almost every page, and the fact that the book succeeds brilliantly anyway is a testament to the power of Steinbeck’s storytelling: to his ferocious will to make sense of his life and his country.

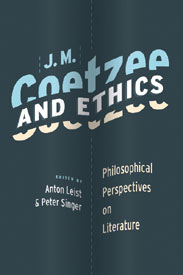

In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from Columbia University Press.

In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from Columbia University Press.

Spanish-language blog La fortaleza de la soledad has republished The Paris Review’s interview with Jonathan Lethem. Cool interview–Lethem talks about his hippie parents, going to school with Bret Easton Ellis, explains why William Gibson is the new Thomas Pynchon, and discusses his novels at length. From the interview —

I felt I ought to thrive on my fate as an outsider. Being a paperback writer was meant to be part of that. I really, genuinely wanted to be published in shabby pocket-sized editions and be neglected—and then discovered and vindicated when I was fifty. To honor, by doing so, Charles Willeford and Philip K. Dick and Patricia Highsmith and Thomas Disch, these exiles within their own culture. I felt that was the only honorable path.