Bloomsday, an annual celebration of James Joyce’s Ulysses, is upon us today with more excitement than ever. Even with the festivities, the book’s reputation for density, erudition, and inscrutability still daunts many readers–leading to a glut of guidebooks, summaries, and annotations. Ironically, rather than inviting first-time readers to the text, the sheer volume of these guides to Ulysses can paradoxically repel. Their very existence seems predicated on an intense need, and although some of the guides out there can be helpful, others can get in the way. This need not be. Ulysses deserves its reputation as one the best books in the English language. It generously overflows with insight into the human experience, and it’s very, very funny. And, most importantly, anyone can read it.

Here are a few thoughts on how to read Ulysses, enumerated–because people like lists:

1. Ignore all guides, lists, maps, annotations, summaries, and lectures. You don’t need them; in fact, they could easily weigh down what should be a fun reading experience. Jump right into the text. Don’t worry about getting all the allusions or unpacking all the motifs.

Pretty soon though, you’ll get to the third chapter, known as “Proteus.” It’s admittedly hard to follow. You might want a guide at this point. Or you might just want to give up. (Of course, you might be a genius and totally get what Stephen is thinking about as he wanders the beach. Good for you). If frustration sets in, I suggest skipping the chapter and getting into the rich, earthy consciousness of the book’s hero, Leopold Bloom in chapter four, “Calypso.” It’s great stuff. You can always go back to chapter three later, of course. The real key, at least in my opinion, to reading (and enjoying) Ulysses is getting into Bloom’s head, matching his rhythm and pacing. Do that and you’re golden.

I’ve already advised you, gentle reader, not to follow any guides, so please, ignore the rest of my advice. Quit reading this post and start reading Ulysses.

For those who wish to continue–

2. Choose a suitable copy of the book. The Gabler edition will keep things neat and tidy and it features wide margins for all those clever game-changing annotations you’ll be taking. Several guides, including Harry Blamire’s The New Bloomsday Book align their annotation to the Gabler edition’s pagination.

3. Make a reading schedule and stick to it. The Gabler edition of Ulysses is nearly 700 pages long. That’s a long, long book–but you can read it in just a few weeks. There are eighteen episodes in Ulysses, some longer and more challenging than others, but reading one episode every two days should be no problem. If you can, try to read one episode in one sitting each day. As the book progresses, you’ll find yourself going back to previous chapters to find the figures, motifs, and traces that dance through the book.

4. So you’ve decided you need a guide. First, try to figure out what you want from the guide. Basic plot summary? Analysis? Explication? There’s plenty out there–too much really–so take the time to try to figure out what you want from a guide and then do some browsing and skimming before committing.

The most famous might be Stuart Gilbert’s James Joyce’s Ulysses, a dour book that manages to suck all the fun out of Joyce’s work. In a lecture on Ulysses, Vladimir Nabokov warned “against seeing in Leopold Bloom’s humdrum wanderings and minor adventures on a summer day in Dublin a close parody of the Odyssey,” noting that “it would be a complete waste of time to look for close parallels in every character and every scene in the book.” Nabokov scathingly continued: “One bore, a man called Stuart Gilbert, misled by a tongue-in-cheek list compiled by Joyce himself, found in every chapter the domination of one particular organ . . . but we shall ignore that dull nonsense too.” It’s perhaps too mean to call Gilbert’s guide “nonsense,” but it’s certainly dull. Harry Blamire’s The New Bloomsday Book is a line-by-line annotation that can be quite helpful when Joyce’s stream of consciousness gets a bit muddy; Blamire’s explications maintain a certain analytical neutrality, working mostly to connect the motifs of the book but letting the reader manage meaning. Don Gifford’s Ulysses Annotated is an encyclopedia of minutiae that will get in the way of any first time reader’s enjoyment of the book. Gifford’s notes are interesting but they can distract the reader from the text, and ultimately seem aimed at scholars and fanatics.

Most of the guidebooks I’ve seen for Ulysses share a common problem: they are obtrusive. I think that many readers who want some guidance or insight to aid their reading of Ulysses, rather than moving between books (what a chore!), should listen to some of the fantastic lectures on Joyce that are available. James Heffernan’s lectures for The Teaching Company provide a great overview of the book with some analysis; they are designed to be listened to in tandem with a reading of the book. Frank Delaney has initiated a new series of podcast lectures called re:Joyce; the first lecture indicates a promising series. The best explication I’ve heard though is a series of lectures by Joseph Campbell called Wings of Art. Fantastic stuff, and probably the only guide you really need. It’s unfortunately out of print, but you can find it easily via extralegal means on the internet. Speaking of the internet–there’s obviously a ton of stuff out there. I’ll withhold comment–if you found this post, you can find others, and have undoubtedly already seen many of the maps, schematics, and charts out there.

5. Keep reading. Reread. Add time to that reading schedule you made if you need to. But most of all, have fun. Skip around. If you’re excited about Molly’s famous monologue at the end of the book, go ahead and read it. Again, the point is to enjoy the experience. If you can trick a friend into reading it with you, so much the better. Have at it.

New York’s WBAI

New York’s WBAI In This Is Where We Live, Janelle Brown’s follow-up to her 2008 début All We Ever Wanted Was Everything, an artsy newly wed couple find their dreams and their marriage unraveling when the payments on their adjustable rate mortgage suddenly double. Claudia and Jeremy are happy at the novel’s outset, living comfortably in their Los Angeles bungalow. Her film Spare Parts garners a huge buzz at Sundance and he reforms a new band after the breakup of his old group The Invisible Spot; they envision their new neighborhood as a contemporary counterpart to the Laurel Canyon creative scene of the 1960s. But then their ARM adjusts and Spare Parts flops. Claudia has to take a job teaching (Gasp! Oh, the terror! In a particularly funny scene, she shows The Graduate to her film students and one of them raises her hand to declare that her father was one of the film’s executive producers). The couple soon has to take in a roommate. Complicating matters even more is the return of Aoki, Jeremy’s unstable–and now famous–ex-girlfriend, who manipulates him every chance she gets. Aoki, a cartoonishly unhinged avant-gardiste, serves as a foil to the more grounded figure of Claudia; as Claudia begins to mature into a more pragmatic, adult personality, Aoki’s siren song calls Jeremy to return to chaos. This Is Where We Live is timely, of course, and Brown takes pains to show how these two “creatives” could overlook such meaningful financial details when looking to buy a home. Some will find Brown’s sympathetic vision of the privileged L.A. art scene off-putting or even shallow, but the novel’s core exploration of a troubled young marriage will resonate with many readers. This Is Where We Live is available in hardback from

In This Is Where We Live, Janelle Brown’s follow-up to her 2008 début All We Ever Wanted Was Everything, an artsy newly wed couple find their dreams and their marriage unraveling when the payments on their adjustable rate mortgage suddenly double. Claudia and Jeremy are happy at the novel’s outset, living comfortably in their Los Angeles bungalow. Her film Spare Parts garners a huge buzz at Sundance and he reforms a new band after the breakup of his old group The Invisible Spot; they envision their new neighborhood as a contemporary counterpart to the Laurel Canyon creative scene of the 1960s. But then their ARM adjusts and Spare Parts flops. Claudia has to take a job teaching (Gasp! Oh, the terror! In a particularly funny scene, she shows The Graduate to her film students and one of them raises her hand to declare that her father was one of the film’s executive producers). The couple soon has to take in a roommate. Complicating matters even more is the return of Aoki, Jeremy’s unstable–and now famous–ex-girlfriend, who manipulates him every chance she gets. Aoki, a cartoonishly unhinged avant-gardiste, serves as a foil to the more grounded figure of Claudia; as Claudia begins to mature into a more pragmatic, adult personality, Aoki’s siren song calls Jeremy to return to chaos. This Is Where We Live is timely, of course, and Brown takes pains to show how these two “creatives” could overlook such meaningful financial details when looking to buy a home. Some will find Brown’s sympathetic vision of the privileged L.A. art scene off-putting or even shallow, but the novel’s core exploration of a troubled young marriage will resonate with many readers. This Is Where We Live is available in hardback from  Little Green, Loretta Stinson’s début novel, tells the story of Janie, an orphan who runs away from her stepmother. Life on the road is tough, and Janie has to make money somehow, dancing in strip bars and even bartering for sex when necessary. When she meets a charmer named Paul who is ten years older than her, she feels instantly closer to him–and naturally hits the road again. Hitchhiking is never a good idea though, kids, especially in a loner’s van, and Janie is brutally beaten. She finds herself under the care of the man who owns the last bar she danced at, and in time, under the care of Paul, reiterating one of the novel’s major themes of cyclical violence and female dependence on a man. Paul is a small-time drug dealer whose habits extend beyond weed and acid into heroin and meth. As his drug addiction spirals, he tries to find some control by manipulating Janie; in time, he beats her so terribly that she has to go to the hospital. Janie leaves him but he stalks her wherever she goes, forcing her to find her own strength and self-reliance as the novel reaches its redemptive climax. Paul is probably the most interesting character in Little Green, and although it would be unfair to call Janie a flat character, she spends much of the novel as a victim. In contrast, Paul’s addiction and behaviors are studied with a psychological depth that attempts to understand–without ever rationalizing–his actions. While the novel is hardly sympathetic to him, Stinson resists painting Paul as a static monster; the payoff is a villain far-more frightening because of his authenticity. Authenticity is what keeps Little Green (for the most part) from verging into melodramatic Lifetime movie of the week territory. Stinson’s finely detailed evocation of the Pacific Northwest

Little Green, Loretta Stinson’s début novel, tells the story of Janie, an orphan who runs away from her stepmother. Life on the road is tough, and Janie has to make money somehow, dancing in strip bars and even bartering for sex when necessary. When she meets a charmer named Paul who is ten years older than her, she feels instantly closer to him–and naturally hits the road again. Hitchhiking is never a good idea though, kids, especially in a loner’s van, and Janie is brutally beaten. She finds herself under the care of the man who owns the last bar she danced at, and in time, under the care of Paul, reiterating one of the novel’s major themes of cyclical violence and female dependence on a man. Paul is a small-time drug dealer whose habits extend beyond weed and acid into heroin and meth. As his drug addiction spirals, he tries to find some control by manipulating Janie; in time, he beats her so terribly that she has to go to the hospital. Janie leaves him but he stalks her wherever she goes, forcing her to find her own strength and self-reliance as the novel reaches its redemptive climax. Paul is probably the most interesting character in Little Green, and although it would be unfair to call Janie a flat character, she spends much of the novel as a victim. In contrast, Paul’s addiction and behaviors are studied with a psychological depth that attempts to understand–without ever rationalizing–his actions. While the novel is hardly sympathetic to him, Stinson resists painting Paul as a static monster; the payoff is a villain far-more frightening because of his authenticity. Authenticity is what keeps Little Green (for the most part) from verging into melodramatic Lifetime movie of the week territory. Stinson’s finely detailed evocation of the Pacific Northwest  of the late 1970s explores how attitudes about gender roles, women’s rights, and drugs came to a seething breaking point a decade after the summer of love. Significantly (and sadly), the novel’s depiction of domestic violence reads with a wholly contemporary immediacy. Little Green is new in handsome trade paperback this month from

of the late 1970s explores how attitudes about gender roles, women’s rights, and drugs came to a seething breaking point a decade after the summer of love. Significantly (and sadly), the novel’s depiction of domestic violence reads with a wholly contemporary immediacy. Little Green is new in handsome trade paperback this month from

On the heels of last year’s hugely successful first-time-in-English publication of Every Man Dies Alone, the good folks at Melville House have issued another of Hans Fallada’s epic novels,

On the heels of last year’s hugely successful first-time-in-English publication of Every Man Dies Alone, the good folks at Melville House have issued another of Hans Fallada’s epic novels,  A lovely little crop of new titles from independent publisher

A lovely little crop of new titles from independent publisher  Frank Meeink’s The Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead–told to Jody M. Roy (in the tradition of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley)–chronicles how one of America’s most notorious neo-Nazis spiraled into a cycle of criminal violence before eventually finding redemption and purpose. Meeink was a guest on NPR’s Fresh Air a few months ago–you can listen to that story

Frank Meeink’s The Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead–told to Jody M. Roy (in the tradition of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley)–chronicles how one of America’s most notorious neo-Nazis spiraled into a cycle of criminal violence before eventually finding redemption and purpose. Meeink was a guest on NPR’s Fresh Air a few months ago–you can listen to that story  (aka Sniffles) as she tries to realize her dreams of artistic freedom through, uh, clowning. But economic realities threaten to force her into satisfying the dark needs of clown fetishists. Damn! Earlier this month

(aka Sniffles) as she tries to realize her dreams of artistic freedom through, uh, clowning. But economic realities threaten to force her into satisfying the dark needs of clown fetishists. Damn! Earlier this month

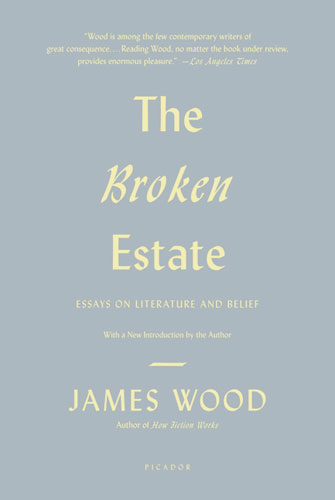

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says– As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–