Early on in W.G. Sebald‘s strange and beautiful novel The Rings of Saturn, the erudite narrator (seemingly) offhandedly alludes to Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving Melencolia I. Rings is larded with such references, stuffed to the gills with analysis of history and literature and art (and so much more), but the quick allusion to Melencolia I seems a particularly informative way of interpreting–or at least comprehending–Sebald’s grand, glorious book. Before we begin though, it will be useful to quickly summarize the plot: In 1992, a German intellectual named W.G. Sebald takes a walking tour of the east coast of England. He visits old English manors, the homes of dead writers, decaying seaside resorts, abandoned islands, and many other melancholy spots. In true King Lear style, he wanders the heath a bit. But this walking tour is not the real plot: no, instead, Sebald, in a casual, sometimes wryly humorous, and mostly melancholy tone reflects on the global and historical implications of a host of subjects far too numerous to try to list here. In other words, this is a very smart book about everything.

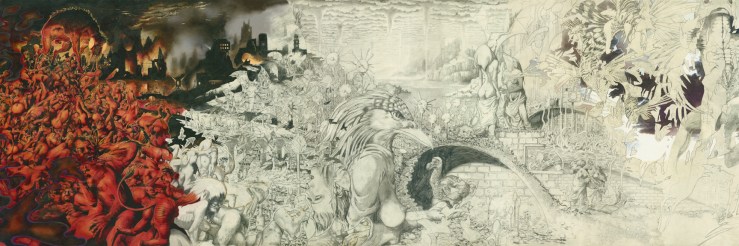

The Rings of Saturn, as its title suggests, is a book about melancholy (Renaissance medical texts identified Saturn with the bodily humor melancholy–black bile–indicated by sluggishness and moroseness, paradoxically paired with an eagerness for action (hence the modern word saturnine)). The melancholy of Rings pervades the whole text and even infiltrates each sentence. Like Dürer’s engraving, Sebald’s text is complexly and richly detailed, overflowing with allusion and symbolic registry that defies simple or easy interpretation. Just as Dürer situates the winged figure of genius at the (slightly off-) center of his image, contemplative yet dreamy, we find Sebald’s narrator to be a flighty genius made forlorn by the world he sees. And yet, just as Dürer’s figure is ultimately ambiguous (is he despondent or merely in the throes of absent fancy? Is he shirking his duty or contemplating a new grand work?) so too does Sebald’s narrator resist any simple interpretation. The narrative bulk of Rings consists of the narrator’s perspectives on history and memory, art and economics, literature and suffering. Like the myriad strange objects that surround the figure of genius in Dürer’s engraving, the connections between the subjects of the narrator’s lessons seem tenuous at first (indeed, several interpretations of Dürer’s piece have argued that it is simply a failed allegorical vision). As the text develops, we begin to see how the narrator’s obsession with, say, Thomas Browne’s skull connects to a biographical account of Joseph Conrad, or early English colonial forays into Imperial China, or reflections on the life cycle of the herring. Like the objects that litter Dürer’s engraving, the narrator’s varied lessons are detailed things, concretizations of history, or art, or literature, or science, and, at the same time–like Dürer’s objects–the narrator’s lessons are also symbols connected to grander abstractions. The work–and joy–of the reader is to link these symbols, these abstractions, into meaning. This is no simple task, but Sebald’s masterful writing ensures that it is a rewarding (and downright fun) adventure.

The flip side to melancholy is the potential energy writhing within its dramatic inertia. The very nature of the narrator’s simple quest–a walking tour–dramatizes this energy; at the same time, the decay and erosion of English coastal life threatens to overwhelm it for good. The narrator’s access to so much human knowledge, both miserable and horrible, attests to the power of history to survive through–but also to paradoxically crush–the living. This paradox of melancholy, dramatized in Dürer’s Melencolia I, is neatly summed up in a line from the first page of The Rings of Saturn (a page I immediately returned to after finishing the book, I must add):

At all events, in retrospect I became preoccupied not only with the unaccustomed sense of freedom but also with the paralysing horror that had come over me at various times when confronted with the traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident to me even in that remote place.

In this “remote place,” this forlorn milieu, Sebald’s narrator (Sebald?) again and again uses the lens of history to–again paradoxically–attempt to come to terms with history, both collective and individual.

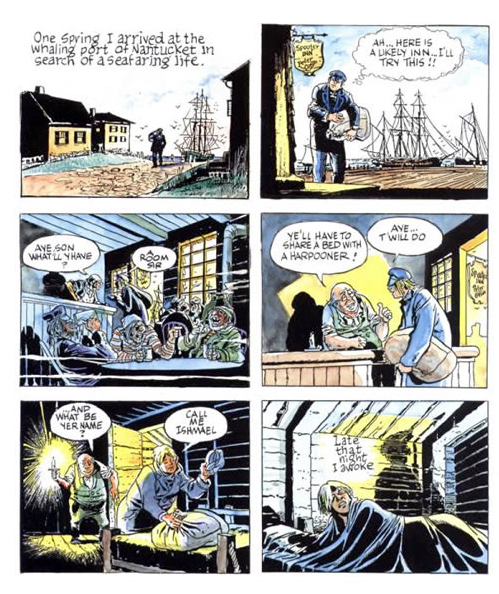

The result of all this is a wonderful, engaging read, on par with the greatest books I’ve read. Sebald’s command of language, his ability to dip into another’s voice recalls Roberto Bolaño’s great work 2666; Sebald’s narrator, in his will to understand and catalog recalls Ishmael in Melville’s masterpiece Moby-Dick, as does his human sympathy, humor, and sensitivity. At the same time, Sebald’s scope spills out of the conventional borders of what we’ve come to know as the novel. While hardly as dry–or neutral–as a history or science text, Sebald’s narrator’s takes on sericulture, or the life of Joseph Conrad, or the relationship between art museums and the sugar trade of the 18th century all vibrate with an intense truthfulness that informs and engages the reader without ever falling into didactic prattle.

At the end of The Rings of Saturn, Sebald’s narrator returns to Thomas Browne’s skull again–only this time resurrected, a living brain. He discusses at length Browne’s Musaem Clausum, an imaginary library that Browne invented containing texts, artifacts, and relics of every manner of wonder. Sebald’s narrator goes on for pages listing the contents of Musaem Clausum with fervor and passion–the reader realizes that the book, and the narrator, could go on and on, detailing these wonders and their connected histories under more intense scrutiny. Rings replicates both Browne’s Musaem Clausum and Dürer’s engraving, offering readers a tour through myriad marvels–and if the walk is melancholy and strange, it is also profound and beautiful, and very, very rewarding. Very highly recommended.

More

More