Through tatter’d clothes small vices do appear;

Robes and furr’d gowns hide all. Plate sin with gold,

And the strong lance of justice hurtless breaks;

Arm it in rags, a pigmy’s straw does pierce it.

King Lear, 4.6

Through tatter’d clothes small vices do appear;

Robes and furr’d gowns hide all. Plate sin with gold,

And the strong lance of justice hurtless breaks;

Arm it in rags, a pigmy’s straw does pierce it.

King Lear, 4.6

A scene from the Peter Brook directed version of King Lear. Cornwall gouges out old man Gloucester’s eyes. The horror!

Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading, hardly short on strong opinions, contains a fantastic chapter on Chaucer, who Pound submits is superior in some ways to Shakespeare. A taste—

Sloth is the root of much bad opinion. It is at times difficult for the author to retain his speech within decorous bounds.

I once heard a man, how has some standing as writer and whom Mr. Yeats was wont to defend, assert that Chaucer’s language wasn’t English, and that one ought not to use it as basis of discussion, ETC. Such was the depth of London in 1910.

Anyone who is too lazy to master the comparatively small glossary necessary to understand Chaucer deserves to be shut out from the reading of good books for ever.

As to the relative merits of Chaucer and Shakespeare, English opinion has been bamboozled for centuries by a love of the stage, the glamour of the theatre, the love of bombastic rhetoric and of sentimentalizing over actors and actresses; these, plus the national laziness and unwillingness to make the least effort, have completely obscured values. People even read translations of Chaucer into a curious compost, which is not modern language but which uses a vocabulary comprehended of sapheads

Wat se the kennath

Chaucer had a deeper knowledge of life than Shakespeare.

Let the reader contradict that after reading both authors, if he chooses to do so.

I recently moved, which means that there’s been a great deal of shuffling around of books. Anyway, I came across these late 1950s Dell editions of Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays with these fantastic covers designed by Jerome Kuhl. The image of Falstaff on the cover of Part One strikes me as both humorous and iconic; the kneeling scene on the cover of Part Two is poignant and even a little sad. Makes me want to reread them.

“Therefore good and ill are one.” Heraclitus, Fragment 57

“Well, um, you know, something’s neither good nor bad but thinking makes it so, I suppose, as Shakespeare said.” Donald Rumsfeld

Harold Bloom’s esteem for Blood Meridian may have done much to advance the novel’s reputation over the past decade. His essay on the book, first published in his 2000 collection How to Read and Why and later included as the preface to Random House’s Modern Library editions, makes a strong case for Blood Meridian’s canonical status. Bloom begins, in typical Bloomian fashion–the anxiety of influence is always at work–by situating McCarthy’s book against other heavies–

Blood Meridian (1985) seems to me the authentic American apocalyptic novel, more relevant even in 2000 than it was fifteen years ago. The fulfilled renown of Moby-Dick and of As I Lay Dying is augmented by Blood Meridian, since Cormac McCarthy is the worthy disciple both of Melville and of Faulkner. I venture that no other living American novelist, not even Pynchon, has given us a book as strong and memorable as Blood Meridian . . .

Bloom goes on to rate Blood Meridian over DeLillo’s Underworld, several books by Philip Roth, and even McCarthy’s own All the Pretty Horses. Indeed, Bloom proclaims Blood Meridian “the ultimate Western, not to be surpassed.” This doesn’t mean that Bloom is at home with the book’s violence; he confesses that it took him two attempts to read through its “overwhelming carnage.” Still, he makes a case for reading it in spite of its gore–

Nevertheless, I urge the reader to persevere, because Blood Meridian is a canonical imaginative achievement, both an American and a universal tragedy of blood. Judge Holden is a villain worthy of Shakespeare, Iago-like and demoniac, a theoretician of war everlasting. And the book’s magnificence–its language, landscape, persons, conceptions–at last transcends the violence, and converts goriness into terrifying art, an art comparable to Melville’s and to Faulkner’s.

Bloom repeatedly invokes Melville and Faulkner in his essay, arguing that Blood Meridian’s “high style” is one of its key strengths (unlike fellow aesthetic critic James Wood, who seems to think that McCarthy is a windbag). The trajectory of Bloom’s essay follows Melville and Shakespeare, finding in Judge Holden both a white whale (and not so much an Ahab) and an Iago. He writes–

Since Blood Meridian, like the much longer Moby-Dick, is more prose epic than novel, the Glanton foray can seem a post-Homeric quest, where the various heroes (or thugs) have a disguised god among them, which appears to be the Judge’s Herculean role. The Glanton gang passes into a sinister aesthetic glory at the close of chapter 13, when they progress from murdering and scalping Indians to butchering the Mexicans who have hired them.

I think that Bloom’s great insight here is to read the book as a prose epic as opposed to a linear novel; to see that Blood Meridian foregrounds a deeply tragic and ironic reworking of the great American myth of Manifest Destiny. While hardly a pastiche, the book is somehow a collage; a massive, deafening collage that numbs, stuns, and overwhelms with its layers of thick, bloody prose. The effect is akin to the apocalyptic paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel. Dense and full of allusion, paintings like The Triumph of Death and The Garden of Earthly Delights surge over the senses, destabilizing narrative logic. Like Blood Meridian, these paintings employ a graphic grammar that disorients and then reorients. They are apocalyptic in all senses of the word: both revelatory and portentously conclusive. And like Blood Meridian, they showcase “a sinister aesthetic glory” (to use Bloom’s term), a terrible, awful, awesome ugliness that haunts us with repulsive beauty.

I hadn’t heard of Conor McCreery and Anthony Del Col’s new comic book series Kill Shakespeare until this afternoon, when I heard Neal Conan interview them on NPR’s Talk of the Nation. From the print edition:

In Kill Shakespeare, Conor McCreery and Anthony Del Col’s graphic novel, the Bard’s heroes and villains conspire to track down the evil wizard, William Shakespeare.

McCreery says you might be surprised at how big the crossover is between Shakespeare and comic books. “Kill Shakespeare‘s actually really done a nice job of reaching out to … the hard-core comic fan,” he tells NPR’s Neal Conan. “But we’ve also had a lot of first-time readers of comics come in because they’re really interested in this whole mash-up of the Bard we’re doing.”

The series brings all of Shakespeare’s trademarks to its panels — action, drama, lust, violence, double-crossing and cross-dressing.

NPR’s also published an excerpt from Kill Shakespeare.

The series seems appealing, and I’m all for anything that might introduce Shakespeare to a wider audience. At the same time, Kill Shakespeare seems indicative of a larger trend of literary mash-ups–think of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, for instance–and I’m not sure how I feel about all of that. But maybe I should go to my local comic book shop and buy an issue and read one of the damn things, and then, you know, make some kind of informed judgment.

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In truth, Bloom’s word invention is an enthusiastic Wildean necessary exaggeration. It is Bloom’s way of registering our almost religious sense that we live in Shakespeare’s shadow and that he does not simply represent human beings but brings new life, more life, into the world. . . . Bloom’s determination to honor Shakespeare’s godly primacy is a kind of secular theology.

The second section of Wood’s essay should be required reading for all English majors (or anyone serious about literary criticism). Here, Wood provides a wonderfully succinct overview of the history of literary criticism, connecting Freudian analysis and the New Critics to the various theories that Bloom would come to call the “The School of Resentment.”  As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

This is a long way around to Bloom, but it may explain the venom and desperation of his attacks. For although deconstruction did not intend to, it has produced mutant modes of reading that, when combined with leftish political guilt or ressentiment, seem to threaten the existence of literature as a discipline.

Wood espouses some common sense here uncommon in literary criticism, taking a long view that recognizes–and attempts to step outside of–the fact that it’s not all academic when it comes to how we read our books. History and politics matter, but so does our passion, our love for our books (as silly as that may sound). He defends Bloom’s work even as he calls it an overreaction. He credits deconstruction as having “produced some brilliance and many distinguished readings (no one could deny the acuities of Derrida, of Paul de Man, of Barbara Johnson).” Wood’s essay “Shakespeare in Bloom” is the kind of thing that students and aspiring critics alike should read before they feel the need to draw arms. You can read it in the second printing (the first in a decade) of Wood’s essay collection The Broken Estate, which debuts in June, 2010 from Picador.

Literature seems to have an ambivalence toward fatherhood that’s too complex to address in a simple blog post–so I won’t even try. But before I riff on a few of my favorite fathers from a few of my favorite books, I think it’s worth pointing out how rare biological fathers of depth and complexity are in literature. That’s a huge general statement, I’m sure, and I welcome counterexamples, of course, but it seems like relationships between fathers and their children are somehow usually deferred, deflected, or represented in a shallow fashion. Perhaps it’s because we like our heroes to be orphans (whether it’s Moses or Harry Potter, Oliver Twist or Peter Parker) that literature tends to eschew biological fathers in favor of father figures (think of Leopold Bloom supplanting Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses, or Merlin taking over Uther Pendragon‘s paternal duties in the Arthur legends). At other times, the father is simply not present in the same narrative as his son or daughter (think of Telemachus and brave Odysseus, or Holden Caulfield wandering New York free from fatherly guidance). What I’ve tried to do below is provide examples of father-child relationships drawn with psychological and thematic depth; or, to put it another way, here are some fathers who actually have relationships with their kids.

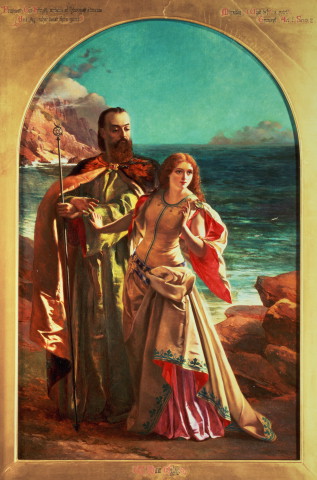

1. Prospero, The Tempest (William Shakespeare)

Prospero has always seemed to me the shining flipside to King Lear’s dark coin, a powerful sorcerer who reverses his exile and is gracious even in his revenge. Where Lear is destroyed by his scheming daughters (and his inability to connect to truehearted Cordelia), Prospero, a single dad, protects his Miranda and even secures her a worthy suitor. Postcolonial studies aside, The Tempest is fun stuff.

2. Abraham Ebdus, The Fortress of Solitude, (Jonathan Lethem)

Like Prospero, Abraham Ebdus is a single father raising his child (his son Dylan) in an isolated, alienating place (not a desert island, but 1970’s Brooklyn). After Dylan’s mother abandons the family, the pair’s relationship begins to strain; Lethem captures this process in all its awkward pain with a poignancy that never even verges on schlock. The novel’s redemptive arc is ultimately figured in the reconciliation between father and son in a beautiful ending that Lethem, the reader, and the characters all earn.

3. Jack Gladney, White Noise (Don DeLillo)

While Jack Gladney is an intellectual academic, an expert in the unlikely field of “Hitler studies” (and something of a fraud, to boot), he’s also a pretty normal dad. Casual reviewers of White Noise tend to overlook the sublime banality of domesticity represented in DeLillo’s signature novel: Gladney is an excellent father to his many kids and step-kids, and DeLillo draws their relationships with a realism that belies–and perhaps helps to create–the novel’s satirical bent.

4. Oscar Amalfitano, 2666 (Roberto Bolaño)

Sure, philosophy professor Amalfitano is a bit mentally unhinged (okay, more than a bit), but what sane citizen of Santa Teresa wouldn’t go crazy, what with all the horrific unsolved murders? After his wife leaves him and their young daughter, Amalfitano takes them to the strange, alienating land of Northern Mexico (shades of Prospero’s island?) Bolaño portrays Amalfitano’s descent into paranoia (and perhaps madness) from a number of angles (he and his daughter show up in three of 2666‘s three sections), and as the novel progresses, the reader slowly begins to grasp the enormity of the evil that Amalfitano is confronting (or, more realistically, is unable to confront directly), and the extreme yet vague danger his daughter is encountering. Only a writer of Bolaño’s tremendous gift could make such a chilling episode simultaneously nerve-wracking, philosophical, and strangely hilarious.

5. The father, The Road (Cormac McCarthy)

What happens when Prospero’s desert island is just one big desert? If there is a deeper expression of the empathy and bonding between a child and parent, I have not read it. In The Road, McCarthy dramatizes fatherhood in apocalyptic terms, positing the necessity of such a relationship in hard, concrete, life and death terms. When the father tells his son “You are the best guy” I pretty much break down. When I first read The Road, I had just become a father myself (my child was only a few days old when I finished it), yet I was still critical of McCarthy’s ending, which affords a second chance for the son. It seemed to me at the time–as it does now–that the logic McCarthy establishes in his novel is utterly infanticidal, that the boy must die, but I understand now why McCarthy would have him live–why McCarthy has to let him live. Someone has to carry the fire.

Every year, I try to pick a different Shakespeare play to read with my students, preferably one I haven’t read in a long time. This year, I have one group of tenth graders, and right now we’re reading A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere on this blog, most of the students at my school read well below their grade level, so Shakespearean language can often be a challenge. I’ve found that Alan Durband’s Shakespeare Made Easy series does a great job at clarifying the narrative action without sacrificing too much of Shakespeare’s poetry. It presents the original text on the left side with the clarified “translation” on the right, which allows us to read and act out the play without spending too much time and effort breaking down every little (or long…) speech. Every couple of pages I’ll pick out a key passage from the original text which we’ll read and discuss. I’ve also been showing them the film adaptation that came out in the nineties (with Kevin Kline, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Christian Bale). We’re about half way through so far, and we’re enjoying the whole process.

I haven’t read this play since I was in the tenth grade, and I really didn’t think too much of it then–it certainly didn’t seem as weighty as, say, Othello, Macbeth, or Hamlet. Anyway, in re-reading it, I notice now that there’s an underlying rape motif throughout the text. For example, Theseus has captured his bride Hippolyta by seizing her in a classical rape; Demetrius threatens taking the “rich worth” of Helena’s virginity if she won’t quit stalking him in the woods; Lysander forces himself onto Hermia in the woods, and she’s barely able to keep him off. Oberon and Titania’s quarrel over the beautiful Indian boy is pretty weird, and is just one strange detail in a play full of aggressive sexuality, possibly most neatly summed up in the bestiality implicit in Titania’s affair with ass-headed Bottom. Of course, Titania doesn’t really love bottom–she’s just been dosed by her jealous hubby, who has a frat boy’s penchant for drugging people to get the love buzz going. Good stuff.

K is for King Richard III, the misanthropic Machiavellian megolomaniacal hero of Shakespeare’s Richard III. Marvel as cruel Richard psychotically removes all those who stand in between him and the throne of England, including his own little nephews. At the same time, sympathize for poor “deformed, unfinish’d” Richard, whose hunchedback and game leg have kept him from any saucy fun with the ladies. Throughout his ambitious quest, Richard wavers from a proto-Iago, devilishly–gleefully even–manipulating the hapless pawns around him, to a manic depressive unhorsed on the battlefield, less than half a man. Poor guy.

Check out Sir Ian McKellen (y’know, Gandalf) doing Richard III in the 1995 film version set in a fictional fascist England of the 1930s. Because, um, Shakespeare’s like, um, better when recontextualized.

1. Titus (1999; directed by Julie Taymor)

Titus Andronicus, one of Shakespeare’s most overlooked plays, comes to lurid, gory glory in this late nineties adaptation. Gang rape, incest, and mutilation mark Titus as one of the downright nastiest Shakespearean works. Throw in a Thyestean banquet, and you’ve got the makings of a nightmare. The villain Aaron is on par with Iago as one of the bard’s greatest baddies.

This trailer makes the movie seem way cheesier than it really is. Trust me.

2. Romeo + Juliet (1996; directed by Baz Luhrmann)

Baz Lurhmann’s take on the ultimate boy-meets-girl story dazzles viewers in a cacophony of glitter and fireworks that captures the sheer silliness of adolescence–the real theme of Romeo and Juliet. Despite a myriad of critical naysayers, I believe Lurhmann’s hypercolor vision far superior to Zeffirelli’s 1968 version (“the one with the boobies”) so often thrust on high school kids. I actually used this version when I used to teach 9th graders. They loved it. I love it too, particularly John Leguizamo’s standout turn as Tybalt.

The first 10 minutes are excellent, if you don’t recall.

3. Macbeth (1972; directed by Roman Polanski)

Another one I show to my students. Polanski’s Macbeth is one of my favorite films, Shakespeare aside. Filmed relatively shortly after Polanski’s wife Sharon Tate was horrifically stabbed to death by the Manson family, Macbeth captures a forbidding spirit of bloody doom, sexual violence, and inescapable guilt. Beautifully shot and superbly acted, every other attempt has paled in comparison.

4. Looking for Richard (1996; directed by Al Pacino)

Wow. What a film. Pacino leads a group of thespians who try to reclaim Shakespeare “from the academics,” as one actor puts it. There’s a problem though: they’re not really sure how Richard III should go. This film captures the pre-production process for a staging of one of Shakespeare’s greatest history plays, revealing a fascinating aspect of adaptation.

This clip sums it up much better than I could:

5. Ran (1985; directed by Akira Kurosawa)

Kurosawa’s take on King Lear proves that the work of one master can be translated into something new and marvelous when placed in the hands of another master. Ran transfers the Lear story to a feudal Japan rife with warring samurai. Ran is at once an epic action film as well as a philosophic meditation on aging, a commentary on gender roles as well as a study on familial duty and love. Again, a Biblioklept fave.

This is one of the best scenes in the film, or any film, really:

6. Henry V (1989; directed by Kenneth Branagh)

Branagh has given the world more filmed adaptations of Shakespeare than would seem possible for someone to do in one lifetime, and the man is still relatively young. That said, at times his work can be stodgy, if not downright plodding. Henry V is not for everyone. This is a very, very long film, and although the battle scenes are exciting, those unfamiliar with the play will no doubt have a hard time following it–particularly the scenes in French which lack subtitles. Still, if you’re studying the Henry tetralogy, or Shakespeare’s English histories in general, then there really isn’t a better supplement. In some ways Henry V is one of the most textually faithful adaptations of a Shakespeare play I can recall. Fans of Braveheart should also note that Mel “Sugartits” Gibson essentially ripped-off large sections of Henry V when crafting that turgid turd.

A famous speech:

7. Prospero’s Books (1991; directed by Peter Greenaway)

One of the Biblioklept’s favorite directors Peter Greenaway (8 1/2 Women; The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover) adapted one of the Biblioklept’s favorite plays, The Tempest, into a very weird, very surreal film called Prospero’s Books. As the title suggests, this is a movie very much about the act of writing itself (a theme Greenaway also explored in his unfortunate fiasco The Pillow Book); more poignant however are the themes of forgiveness and the letting go of the desire for revenge–aspects central to the original play.

Unfortunately, for some reason Prospero’s Books is still not available in DVD, and I have located no news of plans for that to happen any time soon. So, until that time, taste a little sample:

F is for Falstaff, Shakespeare’s knavish knight. Part rascally gnoff, part philosopher, this fat rascal appears in three of the bard’s plays. In Henry IV parts 1 and 2 he advises young Prince Hal (the future king) on matters of honor and drinking. In the comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor, Falstaff tries to cuckold some country farmers and steal their cash; the scalawag’s plans go awry and he ends up wearing the horns. Falstaff is one of Shakespeare’s most verbose characters–only Hamlet has more lines. And despite his fun-loving and roguish nature, Falstaff, like Hamlet, also provides several meditations on human nature, death, and the seeming futility of the individual’s ability to change social order.

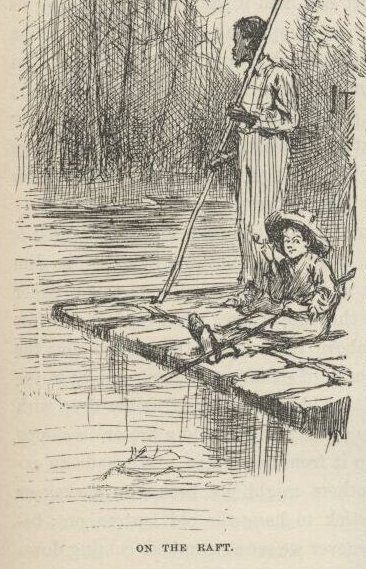

F is also for Finn, Huckleberry. Like Falstaff, Huck Finn is something of a rogue, albeit he is just a child. As the white trash double to middle class Tom Sawyer, Huck is one of Twain’s keenest tools for social satire. Huck escapes the Widow Douglas’s aspirations to give him a moral education, in turn helping her slave Jim make his own escape via the Mississippi River. While navigating the river, Huck must also navigate the perplexing and paradoxical moral codes of the strange South. Despite the happy ending of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the novel remains controversial over a hundred years after its publication, still appearing frequently on lists of challenged books.