Previously,

Stories 60-55

Stories 54-49

Stories 48-43

Stories 42-37

Stories 36-31

Stories 30-25

Stories 24-19

Stories 18-13

Stories 12-7

Stories 6-1

I don’t know if there’s a need for a defense of Donald Barthelme, and I do know that I am not the person to mount that defense. I spent the last two months re-reading Sixty Stories along with/against Tracy Daugherty’s 2010 biography of Barthelme, Hiding Man. I read some other stuff, but most of the writing on this cursed website was about Barthelme’s stories.

Here’s the thing: these stories, even when soaked in the juices of their zeitgeist (“The Sandman,” “The Indian Uprising,” “Robert Kennedy Saved from Drowning”) more than hold up. They are still fresh, funny, strange, charming. I suppose they could be more upsetting–Barthelme’s world is never raw, and always displaces the visceral through a heavy salve of ironic refinements (and a three-martini haze).

But Barthelme’s rhetorical contortions vivify the forms that he parodies here—early French modernism (“Eugénie Grandet”) or Kafkaesque existentialism (“Me and Miss Mandible,” “The Sergeant”) or faux-academic essaying (“On Angels”). He transmutes the material into something more. In his introduction to the 2003 Penguin Classics edition of Sixty Stories that I read, David Gates remarks that,

Barthelme is a quintessential writer of the twentieth century, looking Janus-faced to both the past and future, and with a third eye turned inward. Yet he’s also an anomaly. Nobody before him really reads much like him: neither Beckett or Nabokov, nor such minimalist realists as Hemingway, nor such fabulists as Kafka and Borges…Nor has he become anyone’s Dead Father.

Gates’s appellation “Dead Father” is a nod to Barthelme’s best novel as well as the oedipal undercurrent that surges over and under his ouevre. Gates tries to situate Barthelme’s modernism, a modernism beholden to Dead Father Beckett, himself beholden to Dead Father Joyce.

But Gates never comes out and states what I think is clear after re-reading Sixty Stories (especially against Daugherty’s Barthelme biography)–Barthelme’s success is that he is a failed modernist. In his 1981 interview with J.D. O’Hara, Barthelme stated,

…my father was an architect of a particular kind—we were enveloped in modernism. The house we lived in, which he’d designed, was modern and the furniture was modern and the pictures were modern and the books were modern.

Raised a Modernist, Barthelme transcends Modernism.

And yet he was reticent of any terms that might fix him as something other. In a 1980 interview with Larry McCaffery, he called “‘postmodernism’…the least ugly, most descriptive” of the terms that had been used to pigeonhole his fiction.

He hedged more in his 1987 essay “Not Knowing,” musing that it was “not altogether clear as to who is supposed to be on the bus and who is not.” Postmodernism though is really just a descriptor. And we’re all on the bus.

Gates eventually settles on Barthelme as a “Dark Uncle” of literature, as opposed to a Dead Father. Like Nabokov, Gates suggests Barthelme may have imitators, but not true followers. (Gates does posit the potential of George Saunders to get there, and I’d argue no other living American writer (that I know of) would have at one time been fit to take up the Barthelme mantle, but kudos to Saunders for forging his own schmaltzy overly-empathetic path.)

But enough of Gates’s intro. It’s good. It’s very 2003–mentions of David Eggers, Harold Bloom, a lot of handwringing about postmodernism. (Somehow, unless I’m forgetting, Barthelme’s true contemporary Robert Coover isn’t mentioned.)

Anyway. The stuff in Sixty Stories still shines, still sings–and much of it is far more poignant than I would’ve initially credited.

So here are the silly lists.

If you want to turn Sixty Stories into Thirty Stories, here’s my edit (in reverse chronology):

“Bishop,” (previously uncollected, 1981)

“The Emerald,” (previously uncollected, 1981)

“The King of Jazz,” (Great Days, 1979)

“Cortes and Montezuma,” (Great Days, 1979)

“The Great Hug,” (Amateurs, 1976)

“The School,” (Amateurs, 1976)

“I Bought a Little City,” (Amateurs, 1976)

“At the End of the Mechanical Age,” (Amateurs, 1976)

“A Manual for Sons,” (The Dead Father, 1975)

“Eugénie Grandet,” (Guilty Pleasures, 1974)

“Nothing: A Preliminary Account” (Guilty Pleasures, 1974)

“Daumier” (Sadness, 1972)

“The Rise of Capitalism” (Sadness, 1972)

“The Sandman” (Sadness, 1972)

“The Glass Mountain” (City Life, 1970)

“The Policemen’s Ball” (City Life, 1970)

“Kierkegaard Unfair to Schlegel” (City Life, 1970)

“The Phantom of the Opera’s Friend” (City Life, 1970)

“On Angels” (City Life, 1970)

“Paraguay” (City Life, 1970)

“Views of My Father Weeping” (City Life, 1970)

“The Indian Uprising” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“See the Moon?” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Report” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Robert Kennedy Saved from Drowning” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Game” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

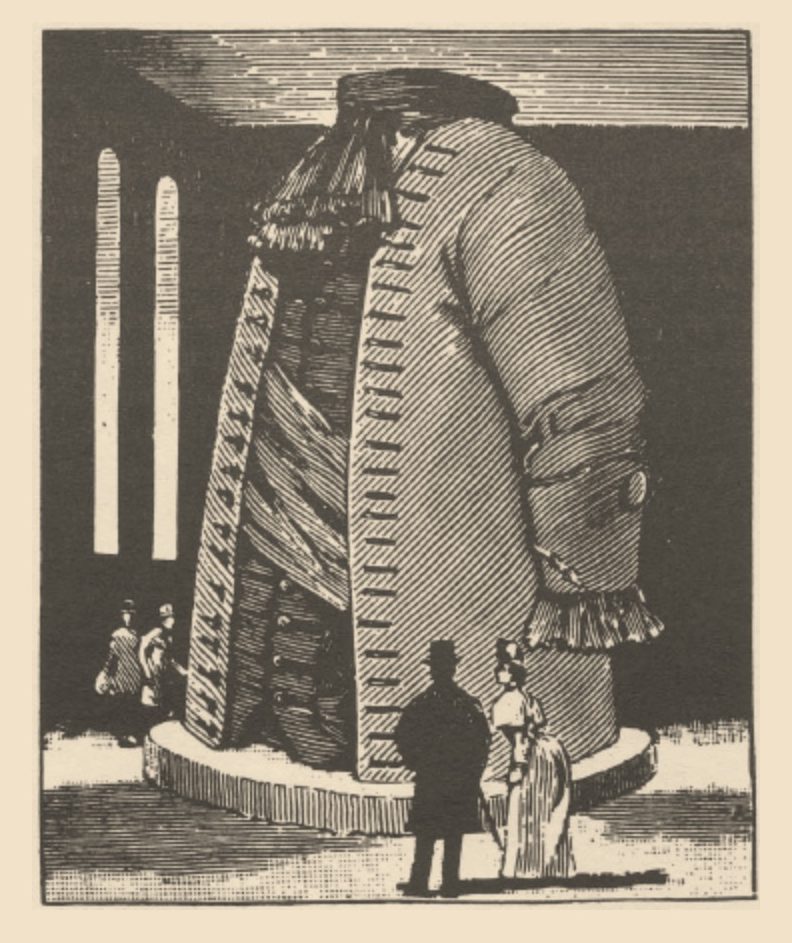

“The Balloon” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“For I’m the Boy” (Come Back, Dr. Caligari, 1964)

“Me and Miss Mandible” (Come Back, Dr. Caligari, 1964)

“A Shower of Gold” (Come Back, Dr. Caligari, 1964)

If you want to turn Sixty Stories into Fifteen Stories, here’s my edit (in reverse chronology):

“The Emerald,” (previously uncollected, 1981)

“The School,” (Amateurs, 1976)

“At the End of the Mechanical Age,” (Amateurs, 1976)

“A Manual for Sons,” (The Dead Father, 1975)

“Eugénie Grandet,” (Guilty Pleasures, 1974)

“Daumier” (Sadness, 1972)

“Kierkegaard Unfair to Schlegel” (City Life, 1970)

“On Angels” (City Life, 1970)

“Paraguay” (City Life, 1970)

“Views of My Father Weeping” (City Life, 1970)

“The Indian Uprising” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Robert Kennedy Saved from Drowning” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Game” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“The Balloon” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Me and Miss Mandible” (Come Back, Dr. Caligari, 1964)

If you want to turn Sixty Stories into Ten Stories, here’s my edit (in reverse chronology):

“The Emerald,” (previously uncollected, 1981)

“A Manual for Sons,” (The Dead Father, 1975)

“Eugénie Grandet,” (Guilty Pleasures, 1974)

“Daumier” (Sadness, 1972)

“Kierkegaard Unfair to Schlegel” (City Life, 1970)

“Views of My Father Weeping” (City Life, 1970)

“The Indian Uprising” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Game” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“The Balloon” (Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968)

“Me and Miss Mandible” (Come Back, Dr. Caligari, 1964)