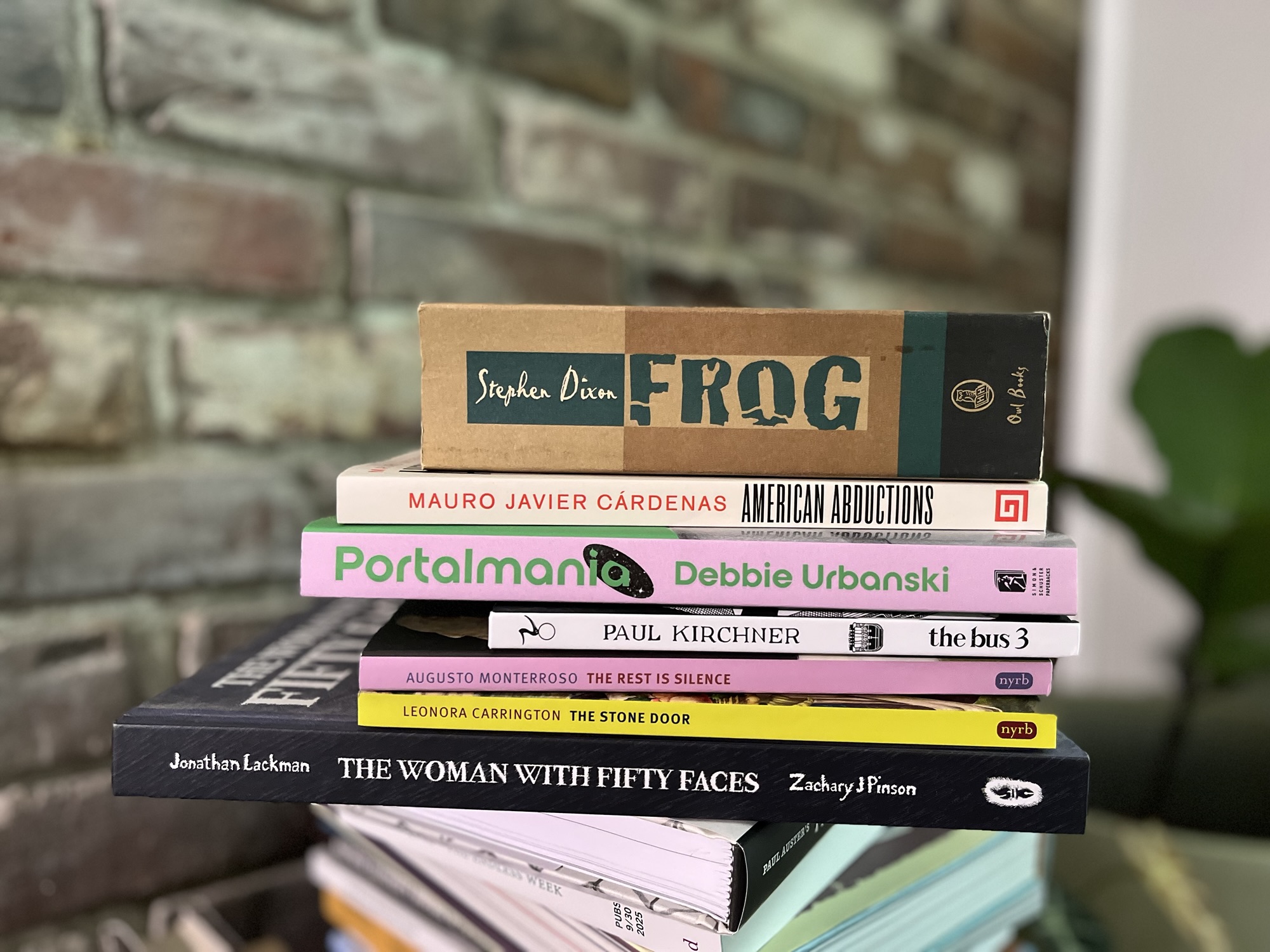

I read one novel in May 2025, the historical graphic biography The Woman with Fifty Faces: Maria Lani and the Greatest Art Heist That Never Was, by Jon Lackman and Zack Pinson. I think it was the only book I’ve read in full in the past two months. It was excellent and I owe it a full review.

I’ve read so so so many Wikipedia pages lately, tunneling down there almost every night (even all night) over the last six weeks. Last night I think I started, for some reason I can’t recall, on Julia Lennon’s page, maybe around eleven pm, and a few hours later I was reading about the visual systems of cuttlefish (this is when my wife woke up and told me to go to sleep). I didn’t start Leonora Carrington’s The Stone Door and I didn’t finish Augusto Monterroso’s The Rest Is Silence, even though they were on my cute little night stand.

I read a big chunk of The Rest Is Silence last Monday at the beach. I took my son and his friends there; despite their claims to being “goth” (or whatever, false claims) they wanted to hang out all day at Hannah Park. So we did that. I walked for a few miles and then discreetly drank a carton of sauvignon blanc and almost finished The Rest Is Silence and then promptly forgot all of the feeling of having read it, having replaced that feeling with the blazing Florida heat (a heat obscured by a heavy gray Atlantic breeze). There was a camp of young musicians wading in the water. I don’t know how I recognized them as teenage musicians, other than years of recognizing such persons in public — the same way I can recognize, say, college football coaches out for barbecue on a Saturday afternoon or late Friday. Some people just look like some people. I chatted with one of the music camp coaches. A lot of these kids hadn’t ever been to the ocean, he assured me, which he didn’t have to. Their movements against the waves showed it. I’m sure they are all graceful with their chosen instruments. Like I said, the slim novella was gone. The sand covered it over (this is a stupid metaphor; I am all rotten inside lately).

I have also not finished Paul Kirchner’s The Bus 3, mostly because I wanted to not finish it, to save it for a different shade of my disposition that is sure to arrive any day now. I love what Paul Kirchner has done, and I have never felt the strips whimsical; or, rather, their whimsy struck me as wise, a sharper whimsy. I’m having a hard time laughing lately.

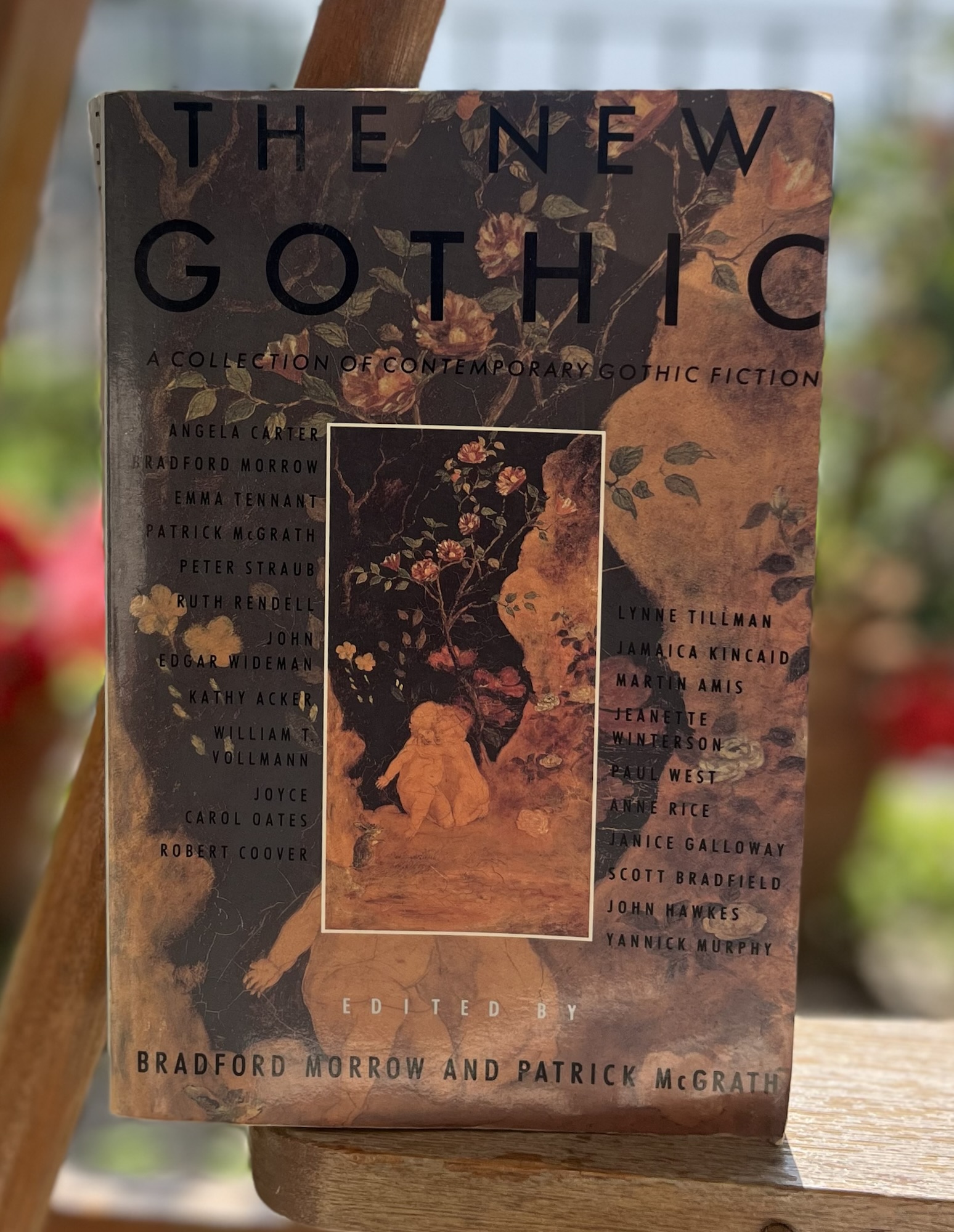

I read a big chunk of an anthology called The New Gothic about three weeks ago. It was in the house we — we my family, my wife and kids — were staying at in Minori, a smallish town in the Amalfi Coast of Italy. We spent the first fifteen days of June in Italy to celebrate my daughter’s 18th birthday and high school graduation. In a lovely little house on the side of a mountain (maybe it was a big hill, I’m a Florida boy), in a small shelf of mostly non-English language books, I picked out The New Gothic and read tales by Coover, Carter, Vollmann and others. The book is a love letter to Poe, really, with a wonderful introductory essay by editors Bradford Morrow and Patrick McGrath.

The story that really stood out though was Lynne Tillman’s “A Dead Summer.” This particular paragraph made me cry:

The Mets were doing better, but with so many new players on the team, she didn’t have the same relationship to them. Her dead friend had loved the Mets too. Sometimes she watched a game just for him, as if he could use her as a medium. She was sure his spirit was hovering near her, especially at those times. But she did not speak of this to her boyfriend who was talking about breaking up. That night she let him gag her. She didn’t have anything to say anyway, not anything worthwhile. She read that the Ku Klux Klan had marched in Palm Beach.

The story is about grief and bad dreams set against a terrifying American political backdrop. The notion of witnessing something so that one’s dead friend might use your eyes as a medium is what did me in. I’ve had such thoughts a few times in the last two months after my best friend died unexpectedly, moments where I thought I might somehow channel his spirit to, say, listen to the new Pulp record. But I don’t think he’s haunting me.

(I didn’t steal The New Gothic from the house in Minori, although I thought about it for two or three minutes.)

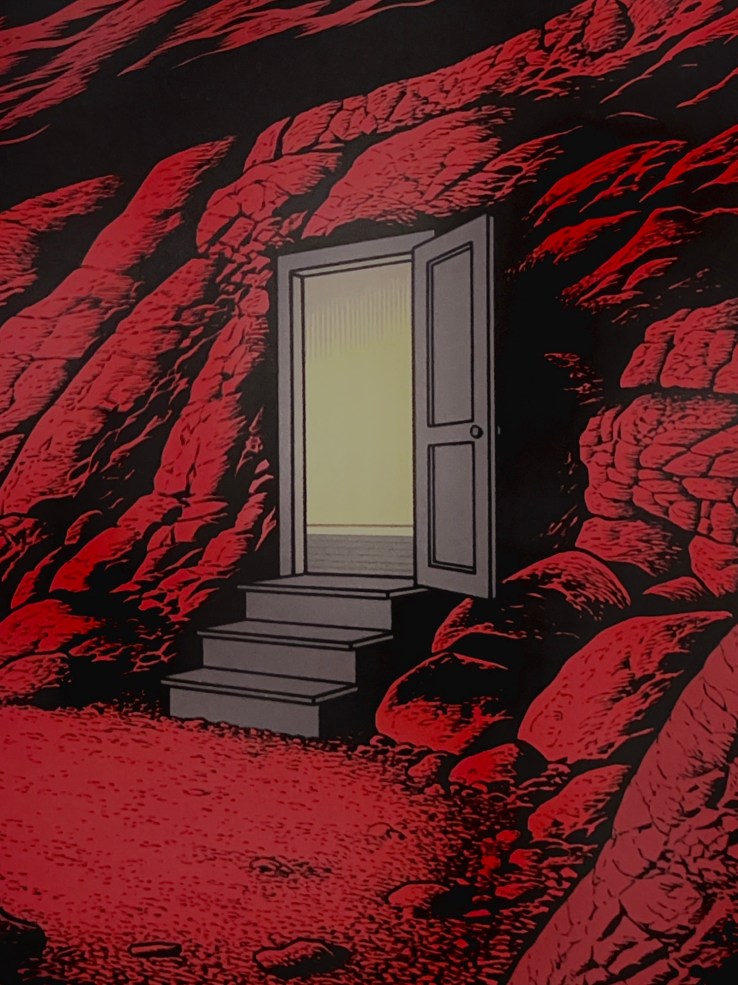

I have almost finished reading the stories in Debbie Urbanski’s collection Portalmania (it is a “collection” but I suspect it is a stealth novel — about escapes, transitions, aesexuality, monsters, uh, portals, etc.). Review to come. (I will absolutely get might shit together, any day now.)

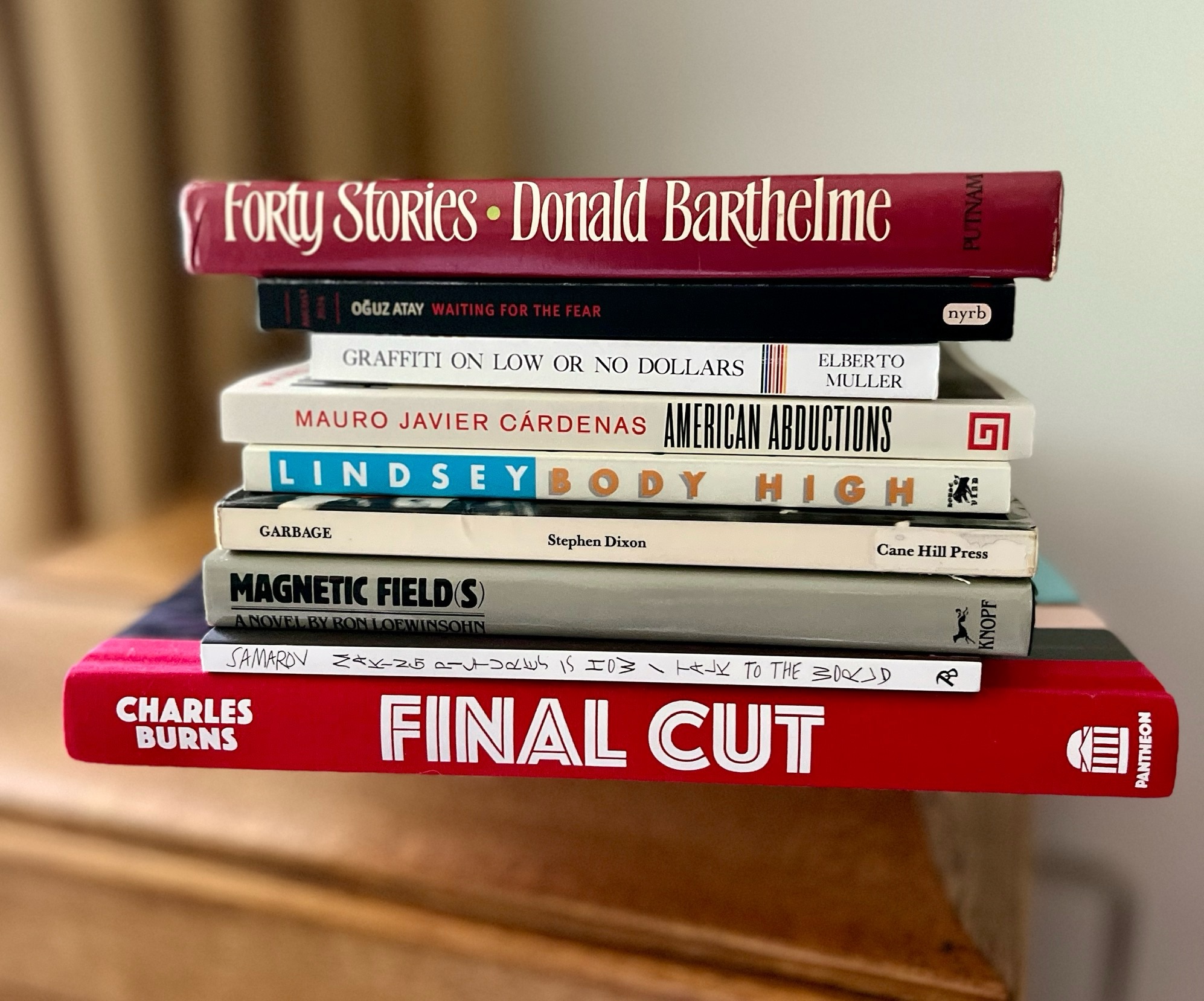

I read and reviewed Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s American Abductions back in March. It’s only in this stack — this organizing picture that I use as an outline — because it is the most timely novel in America right now. It is a novel I read, loved, and highly recommend. Its narrative power surpasses the timeliness I’ve imposed upon it.

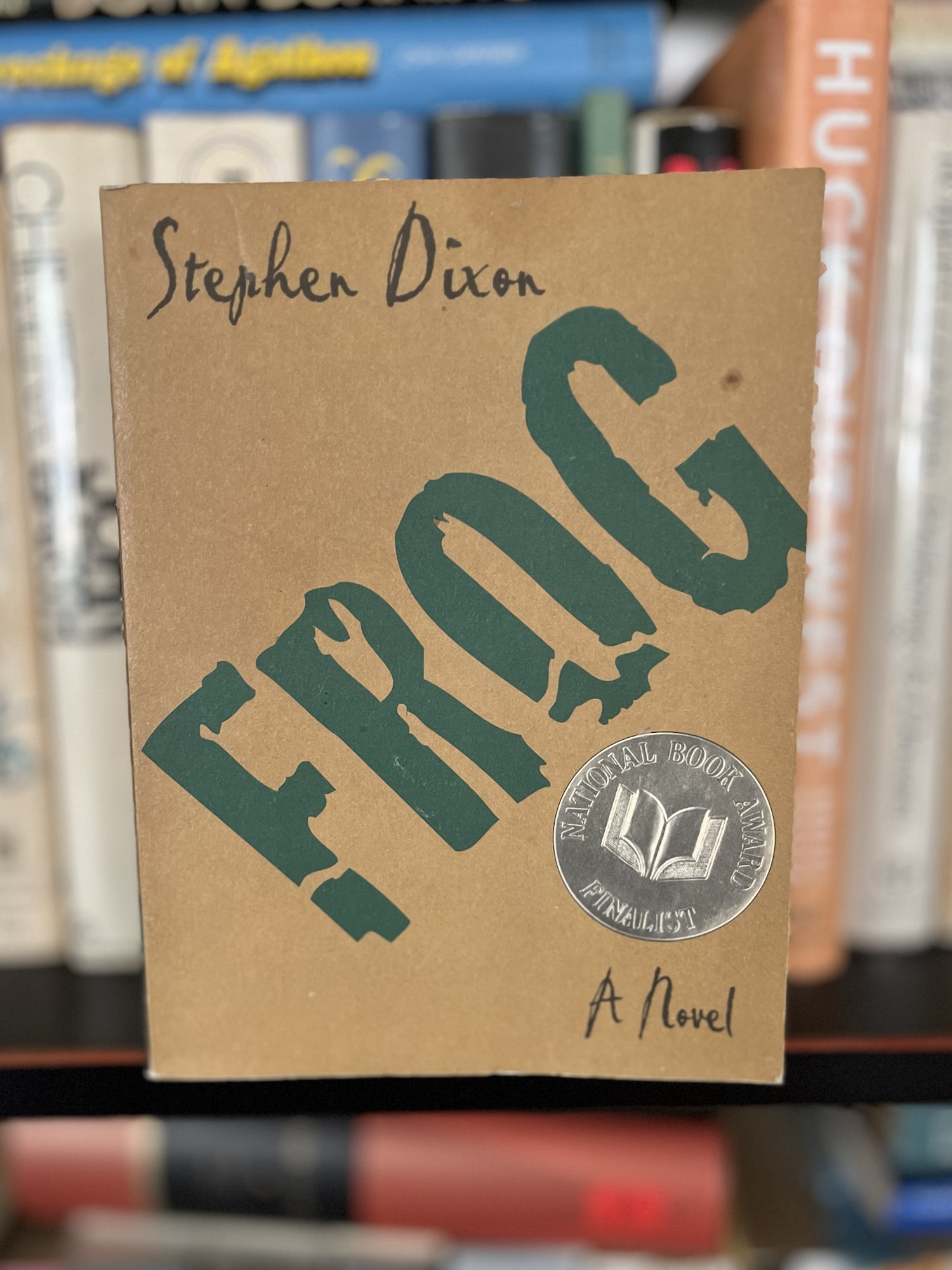

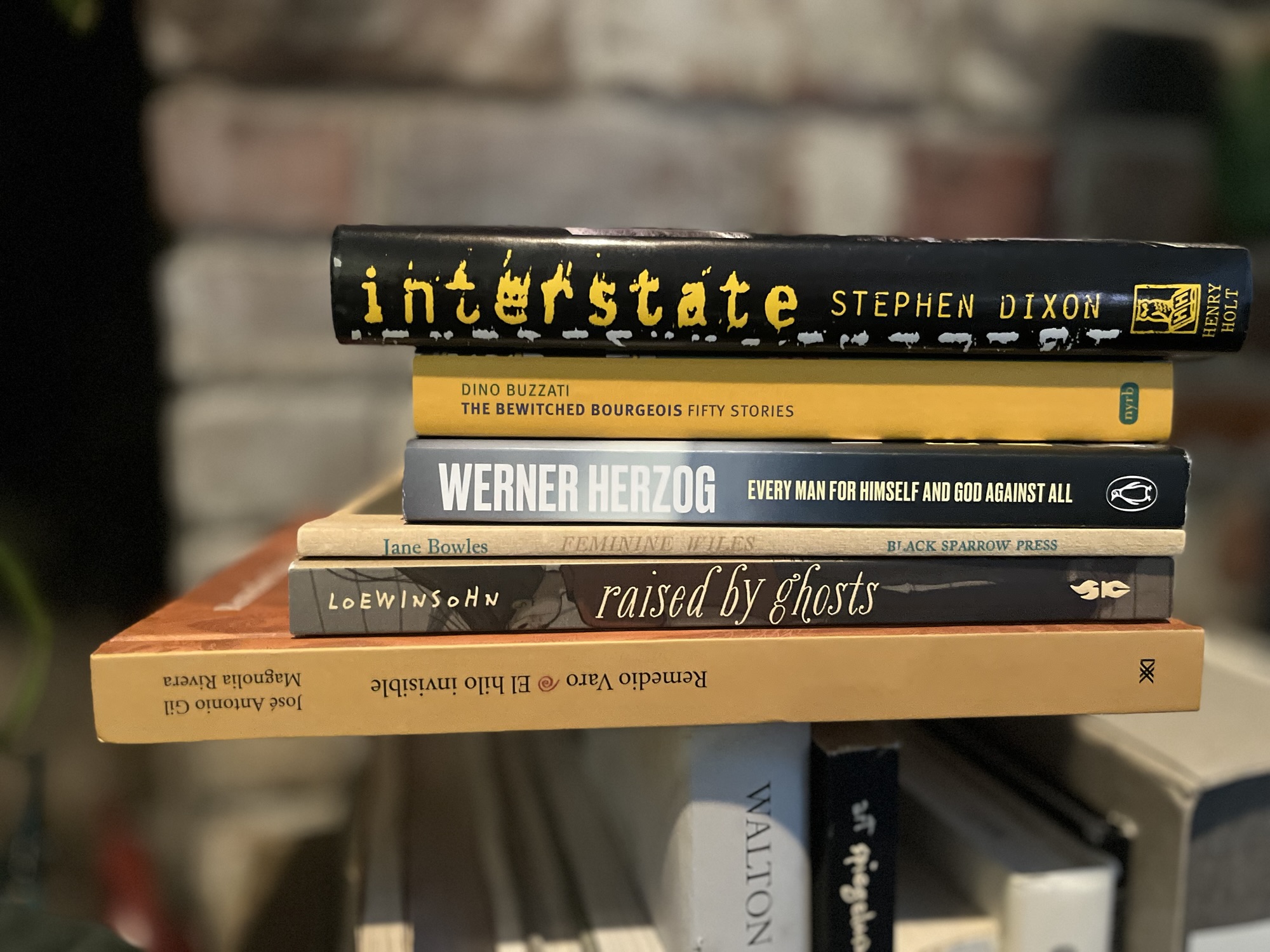

I was, what?, maybe 200, 225 pages? into Stephen Dixon’s massive novel Frog before I abandoned it. I was really loving it, its tics, repetitions, its noisy monotonous howl, its droll jabs at normal fucking people. It could have been one of my favorite novels ever, I think, but I’m not sure I’ll ever wade back in. I tried a few times, but it’s all enmeshed with some bad intense feelings I felt in early May.

Which is what? I guess? another way of saying that reading is just a series of feelings for me now. Maybe at some point I thought of reading novels as an intellectual exercise, and maybe at one point I turned that into an ideal of an aesthetics of reading — but I don’t care about any of that shit now.

I believe in reading for

pleasure

pain

other feelings, in between and otherwise.