The style of this review is probably a bad idea.

In fact, it’s such a bad idea that it’s probable someone has already done it. Or considered doing it but had the good sense to refrain.

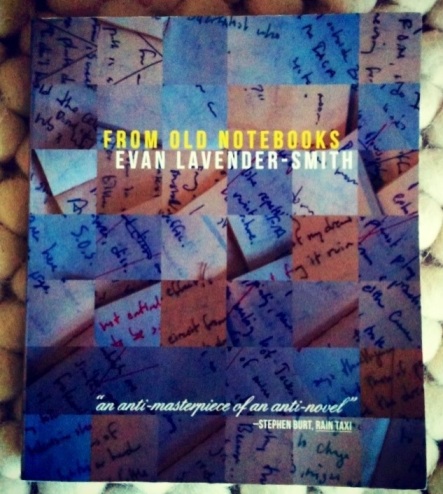

From Old Notebooks as the presentation of a subject through his daily jotting downs.

To clarify: All block quotes—like the one above—belong to Evan Lavender-Smith’s From Old Notebooks.

Which I read twice last month.

And am writing about here.

From Old Notebooks: A Novel: An Essay.

From Old Notebooks: An Essay: A Novel.

From Old Notebooks blazons its anxiety of influence: Ulysses, Infinite Jest, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein. Shakespeare.

Joycespeare.

References, critiques, ideas about Joyce, DFW, Wittgenstein, Nietzsche repeatedly evince in From Old Notebooks—and yet David Markson, whose format E L-S so clearly borrows, is evoked only thrice—and not until page 74 (this in a book of 201 pages):

I count David Markson’s literary-anecdote books among the few things I want to read over and over again, yet I have no idea whether they are actually any good. They’re like porn for English majors.

And then again on page 104:

If David Markson hadn’t written his literary-anecdote novels, would I have ever thought to consider F.O.N. a novel? Would I have ever thought to write such a book?

(I should point out that the page numbers I cite are from Dzanc Book’s first edition of From Old Notebooks; Dzanc’s 2012 printing puts the book back in print).

Like Markson’s anti-novels (Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, The Last Novel), E L-S’s F.O.N. is constantly describing itself.

There may be some question as to F.O.N.’s status as fiction, poetry, philosophy, nonfiction, etc., but hopefully there will be no question about its status as a book.

Is E L-S’s book postmodern? Post-postmodern?

Perhaps there is nothing quintessentially postmodern about the self-reflexivity, fragmentation and pastiche of F.O.N., if only because all of it follows from form.

From Old Notebooks as a document constantly performing its self-critique:

If there were a Viking Portable Lavender-Smith containing an abridgment of F.O.N., I would be very interested to read it, because there’s no reason that the total value of the book wouldn’t be gained, through editorial happenstance, with much greater efficiency.

From Old Notebooks as a document of authorial anxiety.

A reader could make a case that there are a number of elided texts within or suggested by From Old Notebooks, including the one that gives the author the authority to write such a book.

F.O.N. is also a generative text, bustling with ideas for short stories, novels, plays, films, pamphlets, somethings—it is E L-S’s notebook after all (maybe). Just one very short example—

Novel about a haunted cryonics storage facility.

F.O.N.’s story ideas reminded me of my favorite Fitzgerald text, his Notebooks.

Reading From Old Notebooks is a pleasurable experience.

Personal anecdote on the reading experience:

Reading the book in my living room, my daughter and wife enter and begin doing some kind of mother-daughter yoga. My wife asks if they are distracting me from reading. I suggest that the book doesn’t work that way. The book performs its own discursions.

I shared the tiniest morsel here of my family; E L-S shares everything about his family in F.O.N.:

I know that the reconciliation of my writing life and my family life is one of the things that F.O.N. is finally about, but I can’t actually see it in the book; I don’t imagine I could point to an entry and say, Here is an example of that.

It would be impossible for me not to relate to the character of the author or novelist or narrator of F.O.N. (let me call him E L-S as a simple placeholder): We’re about the same age, we both have a son and a daughter (again of similar ages); we both teach composition. Similar literary obsessions. Etc. After reading through F.O.N. the first time I realized how weird it was that I didn’t feel contempt and jealousy for what E L-S pulls off in F.O.N.—that I didn’t hate him for it. That I felt proud of him (why?) and liked him.

There are moments where our obsessions diverge; the E L-S of F.O.N. is preoccupied with death to an extent that I simply don’t connect to. He:

1) Think always about sex. 2) Have a family. 3) Think always about death.

I:

1) Think always about sex. 2) Have a family. 3) Think always about sex.

But generally I get and feel and empathize with his descriptions of his son and daughter and wife.

And his work. Big time:

Getting up the motivation to grade student essays is like trying to pass a piece of shit through the eye of a needle.

Or

I have perfected my lecture after giving it for the third time, but my fourth class never gets to realize it because my voice is hoarse and I’m so tired from giving the same lecture four times in one day, so their experience of my perfect lecture at 8-9:40 PM is of approximately equal value to that of my students receiving my imperfect lecture at 8-9:40 AM, as well as my students at 2:30-3:55 and 5:30-7:10—and it all evens out to uniform mediocrity in the end.

The novel is not jaded or cynical or death-obsessed though (except when it is).

What E L-S is trying to do is to remove as much of the barrier between author and reader as possible:

Contemporary authors who construct a thick barrier between themselves and their readers such that authorial vulnerability is revealed negatively, i.e., via the construction of the barrier.

Perhaps my suggestion that E L-S tries to remove the barrier is wrong. Maybe instead: E L-S’s F.O.N. maps the barrier, points to the barrier’s structure, does not try to deny the barrier, but also tries to usher readers over it, under it, through its gaps—-and in this way channels a visceral reality that so much of contemporary fiction fails to achieve.

I really, really liked this book and will read it again.