; ‘ . . , , , , , , , , , . — — , , . ; – , , , . — — , — — — — – — — — — — — – — — – — — . , , — — . — — — — ? ; . , , , , . , , , , , ; , , , — — — — , – , – . , . , , ; . , , — — — — , , . . . — — — — , , , , . , , — — — — ; . , , , . . , , , , , , , , , , , , , . , , , , – , , , ; , , , , . , , , , , — — , , , , , , , , ” ” — — , , . — — — — . — — ? — — . , , . , , , , — — , , . — — , , , — — , , , , – . , . . . , – . . ; , . – , . , , . , , , , . , . , . , , , , . , , . — — , , , , , , — — — — . , . , , . . . . , , , . , ; , , , . . , , , . , . . , , . , , , , — — . , , . ; , , , . , , , ! . . ; , , ; , ; , ; , , , ; – ; — — , , . , , . , , . , , , , , , , , . — — ; — — . , , , . . ( ) — — , , , – — — , – , , , . , , . , , . , , , — — , , . . , , ; , , . ; ; ; ; ; , , . . ” , ” , ” . , , , . , , . , , , . , , , — — . , , , , . ” , , , , . , , , — — – — — , , , — — , , , , . , , , — — – — — — — , , . ” , ” , , ” ( ) . ” , ( ) , , , . ; . . , , , ; , . . , , . , ; , ( ) ; — — , , . , ; . , , , . , , , , . . , , , . . . , . , , , , — — ( ) . , , . , . , , , , . , , , , . , , , , . . , ; , . , . , , , , . . , , , ( ) , . . , , , , , , , . , ” , ” , , : — — . , , — — — — . ‘ — — ! . . , , , ; ( — — — — ) ; , , , . . ‘ – ; , ( ! ) , . . , , , , , , . . , , ‘ ; ( , , , ! ) , , – . . , – ; , , , , — — . , ‘ ( * ) , . , , . , , , , , . , . , , ( ) . , , — — , , — — , , . — — — — , , ( ) , . , , , — — . , . — — , , — — , , . ” ” ; ” ” ; ” ” ; ” ” ; ” ” , ‘ , ; ” ” ; ” ” . ” , ” ; , , . , , — — — — . , , , , , ( ) , . , , , . ( ) , , – . , , , , . , . , . ( , , ) , , ; , , . , , , – , , , , , , , . , , , , . , , . , , . ; , , , , , . , , — — . , , , , . , , , , , . , , . . . , , . , , — — . ; , , . , , , . , , , , , . — — . , , . , , , . — — . . , , — — , , , , . . ; , , . , , , , — — , — — , , , . , , ( ) , , . , . . , , , , . , , — — , , — — . — — , . ” ? ” , — — ” ? — — , ! . ” , , , . . , , , . ; ; ( ) – , . — — , . , , . ” — — ! ” , , , , , . ” , , — — . ; — — . . , : — — . ” ” ” ; ‘ ; , , . , , ; , ( ) . , , , , , . – , , , . , , : ” , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ; , , , , – . ” , , ; ( ) — — , , , , , , ( ) . , , ; , , , , , , , . : ” , , ; , , , , , ; — — , ; , . , , , , , , , . ” , — — , , ( ) , , , — — ‘ . , , , , , , , . ; , , , , . , , ; , . — — , . , , — — . , , : ” , , , , , , ; , , . ” , — — , , — — , , , , , . , ; . . , . , , ; ; , , , . , . ” ? — — , , . — — — — — — , , , — — — — , , ! — — — — ! ! ? . — — , — — — — ! — — – — — — — ! ! — — ‘ , – , ! — — , , , , ! ! ? ? ? ? ? ! ” — — , , — — ” ! ! ” , , , . — — . , . — — , , , – , , . , , . . , ; . , , – – , , . , — — — — — — — — — — ” . ” * , . , , . — — ” , ” . .

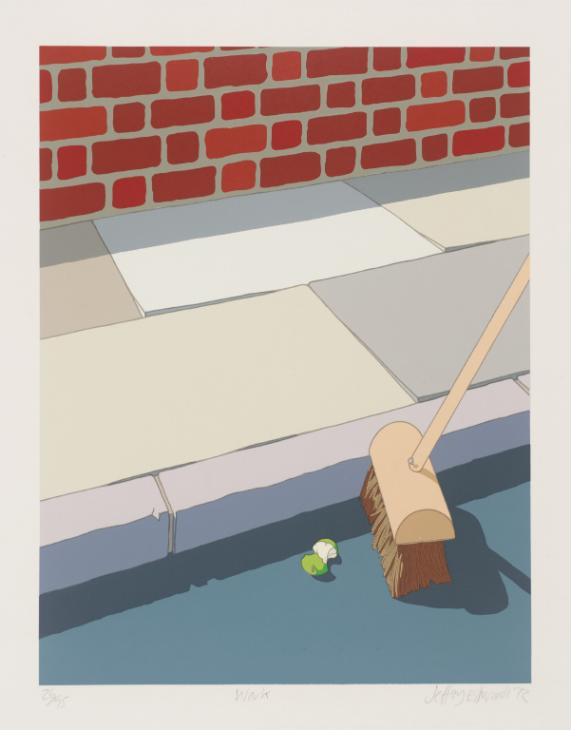

Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” but just the punctuation.