Author: Biblioklept

A lurid paperback copy of Harry Crews’s lurid novel A Feast of Snakes (Lurid book acquired, 14 May 2021)

I love to browse my local used bookstore of a Friday afternoon. This afternoon I came across a copy of my favorite Harry Crews novel, A Feast of Snakes. It’s a 1978 massmarket edition from Ballantine. The lurid cover captures the novel’s lurid spirit. It wraps around; here’s the back (I’d scan the whole thing flat but I don’t think the book’s spine would survive):

The art seems to be signed with the (last I’m guessing?) name “Gentile.” If anyone can confirm I’d appreciate it.

I shared the cover on Twitter, where one user pointed out that the publishers seemed to be “pre-emptively casting the film,” with Ed Asner in a supporting role. I’m guessing they would’ve wanted Burt Reynolds for Joe Lon.

The cover captures the sweaty abjection of A Feast of Snakes—it’s a nasty, gnarly novel that pushes the so-called “Southern Grotesque” style into new, gross, territory. If you haven’t read Crews, it’s a perfect starting point (although I’m sure that the novel is like, problematic or whatever in many, many ways). I love the cover, as I’ve said–it fits the novel wonderfully, unlike the more “respectable” cover for my 1998 edition (which I’ll be trading in now):

From the novel: not quite a recipe for snakes:

When they got to his purple double-wide, Joe Lon skinned snakes in a frenzy. He picked up the snakes by the tails as he dipped them out of the metal drums and swung them around and around his head and then popped them like a cowwhip, which caused their heads to explode. Then he nailed them up on a board in the pen and skinned them out with a pair of wire pliers. Elfie was standing in the door of the trailer behind them with a baby on her hip. Full of beer and fascinated with what Joe Lon could feel—or thought he could—the weight of her gaze on his back while he popped and skinned the snakes. He finally turned and looked at her, pulling his lips back from his teeth in a smile that only shamed him.

He called across the yard to her. “Thought we’d cook up some snake and stuff, darlin, have ourselves a feast.”

Her face brightened in the door and she said: “Course we can, Joe Lon, honey.”

Elfie brought him a pan and Joe Lon cut the snakes into half-inch steaks. Duffy turned to Elfie and said: “My name is Duffy Deeter and this is something fine. Want to tell me how you cook up snakes?”

Elfie smiled, trying not to show her teeth. “It’s lots of ways. Way I do mostly is I soak’m in vinegar about ten minutes, drain’m off good, and sprinkle me a little Looseanner redhot on’m, roll’m in flour, and fry’m is the way I mostly do.”

The novel should now try simply to be Funny, Brutalist, and Short | From B.S. Johnson’s novel Christie Marly’s Own Double-Entry

‘Christie,’ I warned him, ‘it does not seem to me possible to take this novel much further. I’m sorry.’

‘Don’t be sorry,’ said Christie, in a kindly manner, ‘don’t be sorry. We don’t equate length with importance, do we ? And who wants long novels anyway ? Why spend all your spare time for a month reading a thousand-page novel when you can have a comparable aesthetic experience in the theatre or cinema in only one evening ? The writing of a long novel is in itself an anachronistic act : it was relevant only to a society and a set of social conditions which no longer exist.’

‘I’m glad you understand so readily,’ I said, relieved.

‘The novel should now try simply to be Funny, Brutalist, and Short,’ Christie epigrammatised.

‘I could hardly have expressed it better myself,’ I said, pleased, ‘I’ve put down all I have to say, or rather I will have done in another twenty-two pages, so surely. . . .”

‘So I do go on a little longer ?’ interrupted Christie.

‘Yes, Christie, you go on to the end,’ I assured him, and myself went on : ‘Surely no reader will wish me to invent anything further, surely he or she can extrapolate only too easily from what has gone before ?’

‘If there is a reader,’ said Christie. ‘Most people won’t read it.’

‘Politicians, policemen, some educators and many others treat “most people” as idiots.’

‘So writers may too ?’

‘On the contrary. “Most people” are right not to read novels today.’

‘You’ve said all this before.’

‘I’m very likely to say it again, too, since it’s true.’

A pause. Then suddenly Christie said :

‘Your work has been a continuous dialogue with form ?’

‘If you like,’ I replied diffidently.

‘Only one of the things it’s been,’ said Christie generously. ‘It’s something to aspire to, becoming a critic ! Though there are too many exclamation marks in this novel already.’

Another pause. One of the girls in what is ill-reputed to be a brothel opposite hung out the shirt of what might be her ponce. Christie smiled gently, turned back to me.

‘But I am to go on for a while ?’

‘Of course,’ I assured him again.

‘Until I have everything ?’

‘Yes, Christie, until you have everything.’

The excerpt above is the complete text of Ch. XXI of B.S. Johnson’s 1973 novel, Christie Marly’s Own Double-Entry. The title of the chapter is “In which Christie and I have it All Out; and which You may care to Miss Out.” The chapter begins with this epigraph:

. . . the novel, during its metamorphosis in respect of content and form, necessarily regards itself ironically. It denies itself in parodistic forms in order to be able to outgrow itself.

Széll Zsuzsa

Válságés regény (p. 101)

Akadémia (Hungary) 1970

transl. by Novák Gyorgy

This particular chapter might stand as a synecdoche of Christie Marly’s Own Double-Entry itself.

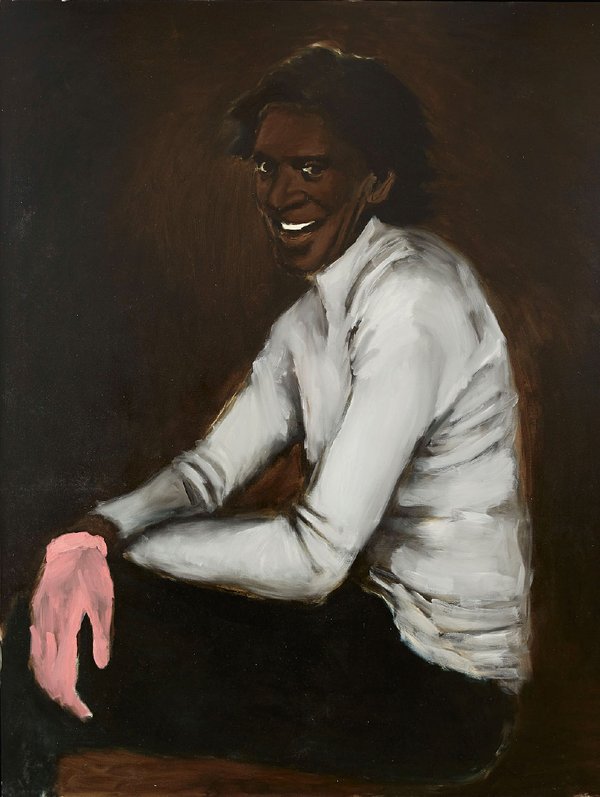

Wrist Action — Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Wrist Action, 2010 by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b. 1977)

Watch — Eric Fischl

Watch, 2015 by Eric Fischl (b. 1948)

“Once There Came a Man” — Stephen Crane

Nanny, Small Bears and Bogeyman — Paula Rego

Nanny, Small Bears and Bogeyman, 1982 by Paula Rego (b. 1935)

Four novels by the sixties avant-garde novelist B.S. Johnson (Books acquired the first week of May, 2021)

I think the first time I heard of the British experimental novelist B.S. Johnson was some time around 2008 or so, when New Directions republished his “book in a box,” The Unfortunates (1969). I thought it sounded like a cool but maybe gimmicky idea at the time, and then Johnson dropped off my radar until more recently. I started to see his name pop up when I’d search out more information about the British avant-garde novelist Ann Quin, whose novel Berg I consider perfect.

So I asked around and ended up finding an online copy of Picador’s omnibus reissue of three of Johnson’s novels: Albert Angelo (1964), Trawl (1966), and House Mother Normal (1971). I also ordered Johnson’s penultimate novel Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry (1973) (as well as a copy of The Unfortunates which has yet to arrive).

I tucked into the omnibus last week, starting with Albert Angelo, which I think is the superior of the three novels the edition collects (I’ve still got a final third of Trawl to go, but I can’t see it turning a corner). AA is an experimental pastiche, a bildungsroman that ironizes the künstlerroman. Our hero Albie, trained as an architect, makes his so-called living as a substitute teacher in some of London’s rougher schools. His narrative is an assemblage of stream-of-consciousness, dramatic dialogues, advertisements, and other rhetorical techniques—including literally cutting out parts of a few pages.

Albie is angry and witty and generally good company throughout the brief novel. Albert Angelo will resonate with teachers who remember those rough first years—sympathy with the students, anger at the system, but also a realization that they are in a kind of battle to earn the respect of their pupils. (Near the end of the novel, we get a litany of student essays that Albie has assigned. The subject: Albie himself. Student reviews are, for the most part, scathing.) Johnson’s assemblage is impressive, energetic, and still feels fresh over fifty years later.

House Mother Normal is also a lively novel, with an energy we might not expect in a novel subtitled A Geriatric Comedy. The novel takes place over a few hours in a single day in a nursing homes, telling the same “narrative” from the viewpoint of eight residents—as well as the titular house mother. Each resident (and the house mother) gets twenty-one pages to relate their version of the days events. Or, more accurately, we dwell in their consciousness for those twenty-one pages. Some residents are of clearer minds than others, but together, they offer a fragmented minor Sadean saga that is both abject and occasionally moving.

Trawl is a more “traditional” novel, at least in the modernist sense. Unlike House Mother Normal and Albert Angelo, Trawl takes a straightforward, stream-of-consciousness first-person tack, detailing three weeks the narrator—a version of Johnson himself—spent on a deep-sea trawler in the Barents Sea. It’s a sort of memoir, loosely figured around the various women that the narrator has successfully or unsuccessfully bedded, with dips into his childhood billeted away from his London family in World War II. In between, we get snapshots of life on the trawler. The unifying theme of the book is shame, paralleled with the narrator’s desire to create a work of Great Art. The narrator peppers his memoir with interjections that the whole thing is boring, worthless, and meaningless. Like I mentioned above, I haven’t gotten to the end of Trawl, but it became a slog about a third of the way in. Johnson’s narrator hems and haws, hedges and defers—and comments on his hemming and hawing. It seems to approach the confessional style of American poetry in the l950s and 1960s without revealing too much. I don’t know. There’s something guarded about it, even as it tries to be a naked affair. I’m hoping I like Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry more. Here’s publisher New Direction’s blurb:

In a brief but productive career, B.S. Johnson (1933-73) was recognized as the most original of the English experimental writers of his generation. Combining a bellicose avant-gardism with pointed social concerns, he won the praise of critics and fellow writers as well as a readership not usually gained by a literary maverick. Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry is Johnson’s most broadly humorous book, though as readers will discover, his humor has a bite. Christie is a simple man. His job in a bank puts him next to but not in possession of money. He encounters the principles of Double-Entry Bookkeeping and adapts them in his own dramatic fashion to settle his account with society. Under the column headed “Aggravation” for offenses received from society (the unpleasantness of the bank manager is the first on an ever-growing list), debit Christie; under “Recompense,” for offenses given back (scratching the façade of an office block), credit Christie. All accounts are to be settled in full, and they are — in the most alarming way.

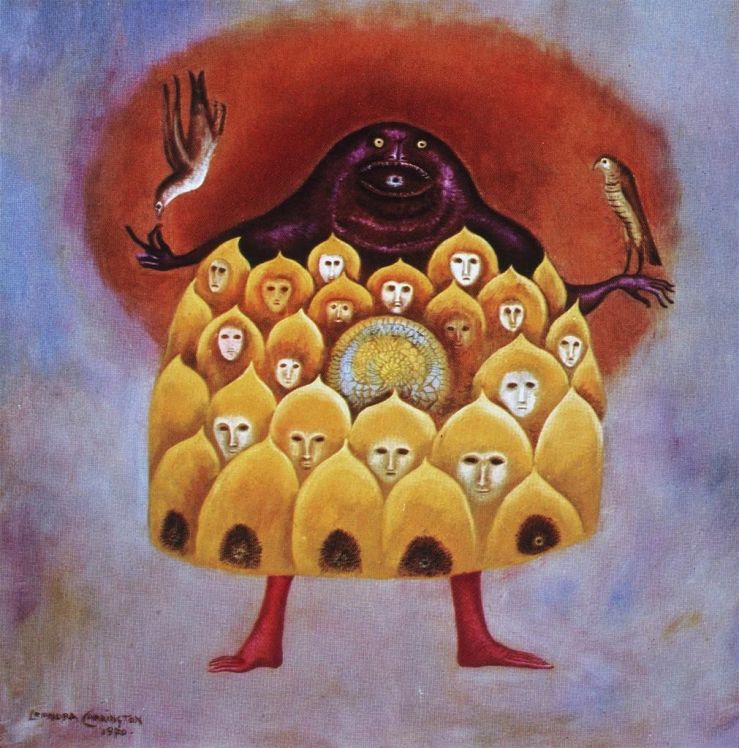

The God Mother — Leonora Carrington

The God Mother, 1970 by Leonora Carrington (1917–2011)

A few sentences on every Thomas Pynchon novel to date

Today, 8 May 2021, is Thomas Ruggles Pynchon’s 84th birthday. Some of us nerds celebrate the work of one of the world’s greatest living authors with something called Pynchon in Public Day. In the past I’ve rounded up links to Pynchon stuff on Biblioklept and elsewhere. Last year, that weird pandemic year, I finally finished all of Pynchon’s novels. I’d been “saving” Bleeding Edge for a while, but broke down and read it that spring. Having read all eight Pynchon novels (a few more than once), I’ll offer some quick scattershot thoughts.

I reread Pynchon’s first novel for the first time last month and found it far more achieved than I had remembered. For years I’ve always recalled it as a dress rehearsal for the superior and more complex Gravity’s Rainbow. And while V. certainly points in GR’s direction, even sharing some characters, it’s nevertheless its own entity. I first read V. as a very young man, and as I recall, thought it scattershot, zany, often very funny, but also an assemblage of set pieces that fail to cohere. Rereading it two decades later I can see that there’s far more architecture to its plot, a twinned, yoyoing plot diagrammed in the novel’s title. The twin strands allow Pynchon to critique modernism on two fronts, split by the world wars mark the first half of the twentieth century. It’s a perfect starting point for anyone new to Pynchon, and its midpoint chapter, “Mondaugen’s Story,” is as good as anything else he’s written.

The Crying of Lot 49 (1966)

Pynchon’s shortest novel is not necessarily his most accessible: Crying is a dense labyrinth to get lost in. At times Pynchon’s second novel feels like a parody of L.A. detective noir (a well he’d return to in Inherent Vice), but there’s plenty of pastiche going on here as well. For example, at one point we are treated to a Jacobean revenge play, The Courier’s Tragedy, which serves as a kind of metatextual comment on the novel’s plot about a secret war between secret armies of…letter carriers. The whole mailman thing might seem ridiculous, but Pynchon’s zaniness is always doubled in sinister paranoia: The Crying of Lot 49 is a story about how information is disseminated, controlled, and manipulated. Its end might frustrate many readers. We never get to hear the actual crying of lot 49 (just as we never discover the “true” identity of V in V.): fixing a stable, centered truth is an impossibility in the Pynchonverse.

Unbelievably rich, light, dark, cruel, loving, exasperating, challenging, and rewarding, Pynchon’s third novel is one of a handful of books that end up on “difficult novel” lists that is actually difficult. The difficulty though has everything to do with how we expect a novel to “happen” as we read—Gravity’s Rainbow is an entirely new thing, a literature that responds to the rise of mass media as modernist painters had to respond to the advent of photography and moving pictures. The key to appreciating and enjoying Gravity’s Rainbow, in my estimation, is to concede to the language, to the plasticity of it all, with an agreement with yourself to immediately reread it all.

Vineland (1990)

It took Pynchon a decade and a half to follow up Gravity’s Rainbow. I was a boy when Vineland came out—it was obviously nowhere on my radar (I think my favorite books around this time would probably have been The Once and Future King, The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and likely a ton of Dragonlance novels). I do know that Vineland was a disappointment to many fans and critics, and I can see why. At the time, novelist David Foster Wallace neatly summed it up in a letter to novelist Jonathan Franzen: “I get the strong sense he’s spent 20 years smoking pot and watching TV.” Vineland is angry about the Reagan years, but somehow not angry enough. The novel’s villain Brock Vond seems to prefigure the authoritarian police detective Bigfoot Bjornsen of Inherent Vice, but Pynchon’s condemnation of Vond never quite reconciles with his condemnation of the political failures of the 1960s. Vineland is ultimately depressing and easily my least-favorite Pynchon novel, but it does have some exquisite prose moments.

If Mason & Dixon isn’t Pynchon’s best book, it has to be 1A to Gravity’s Rainbow’s 1. The novel is another sprawling epic, a loose, baggy adventure story chronicling Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon’s Enlightenment effort to survey their bit of the Western World. Mason & Dixon presents an initial formal challenge to its reader: the story is told in a kind of (faux) 18th-century vernacular. Diction, syntax, and even punctuation jostle the contemporary ear. However, once you tune your ear to the (perhaps-not-quite-so-trustworthy) tone of Rev. Wicks Cherrycoke (who tells this tall tall tale), Mason & Dixon somehow becomes breezy, jaunty, even picaresque. It’s jammed with all sorts of adventures: the talking Learned English Dog, smoking weed with George Washington, Gnostic revelations, Asiatic Pygmies who colonize the missing eleven days lost when the British moved from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar…Wonderful stuff. But it’s really the evocation of a strange, hedged, incomplete but loving friendship that comes through in Mason & Dixon.

Oof. She’s a big boy. At over a thousand pages, Against the Day is Pynchon’s longest novel. Despite its size, I think Against the Day is the best starting point for Pynchon. It offers a surprisingly succinct and clear summation of his major themes, which might be condensed to something like: resist the military-industrial-entertainment-complex, while also showing off his rhetorical power. It’s late period Pynchon, but the prose is some of his strongest stuff. The songs are tight, the pastiche is tighter, and the novel’s epic sweep comes together in the end, resolving its parodic ironies with an earnest love that I believe is the core of Pynchon’s worldview. I forgot to say what it’s about: It’s about the end of the nineteenth century, or, more accurately, the beginning of the twentieth century.

Inherent Vice is a leaner work than its two predecessors, but could stand to be leaner still. The book pushes towards 400 pages but would probably be stronger at 200—or 800. I don’t know. In any case, Inherent Vice is a goofy but sinister stoner detective jaunt that frags out as much as its protagonist, PI Doc Sportello. Paul Thomas Anderson’s film adaptation finds its way through those fragments to an end a bit different from Pynchon’s original (which is closer to an echo of the end of The Crying of Lot 49)—PTA’s film finds its emotional resolution in the restoration of couple—not the main couple, but adjacent characters—an ending that Pynchon pulled in his first novel V.

While Bleeding Edge was generally well received by critics, it’s not as esteemed as his major works. I think that the novel is much, much better than its reputation though (even its reputation among Pynchon fans. Pynchon retreads some familiar plot territory—this is another detective novel, like Crying and Inherent Vice—but in many ways he’s doing something wholly new here: Bleeding Edge is his Dot Com Novel, his 9/11 Novel, and his New York Novel. It’s also probably his domestic novel, and possibly (dare I?) his most autobiographical, or at least autobiographical in the sense of evoking life with teenagers in New York City, perhaps drawing on material from his own life with wife and son in the city. It’s good stuff, but I really hope we get one more.

Rachel Eisendrath’s Gallery of Clouds (Book acquired, like maybe three weeks ago?)

Rachel Eisendrath’s Gallery of Clouds is new in hardback (?!) from NYRB. The book showed up a few weeks ago at Biblioklept International Headquarters on a week when like six books showed up. I finally got into it the other week, and it’s cool stuff. Gallery of Clouds has a Sebaldian vibe—discursive, academic, encyclopedic, and frank, with lots of black and white photographs—but it’s also its own thing.

NYRB’s blurb:

Largely unknown to readers today, Sir Philip Sidney’s sixteenth-century pastoral romance Arcadia was long considered one of the finest works of prose fiction in the English language. Shakespeare borrowed an episode from it for King Lear; Virginia Woolf saw it as “some luminous globe” wherein “all the seeds of English fiction lie latent.” In Gallery of Clouds, the Renaissance scholar Rachel Eisendrath has written an extraordinary homage to Arcadia in the form of a book-length essay divided into passing clouds: “The clouds in my Arcadia, the one I found and the one I made, hold light and color. They take on the forms of other things: a cat, the sea, my grandmother, the gesture of a teacher I loved, a friend, a girlfriend, a ship at sail, my mother. These clouds stay still only as long as I look at them, and then they change.”

Gallery of Clouds opens in New York City with a dream, or a vision, of meeting Virginia Woolf in the afterlife. Eisendrath holds out her manuscript—an infinite moment passes—and Woolf takes it and begins to read. From here, in this act of magical reading, the book scrolls out in a series of reflective pieces linked through metaphors and ideas. Golden threadlines tie each part to the next: a rupture of time in a Pisanello painting; Montaigne’s practice of revision in his essays; a segue through Vivian Gordon Harsh, the first African American head librarian in the Chicago public library system; a brief history of prose style; a meditation on the active versus the contemplative life; the story of Sarapion, a fifth-century monk; the persistence of the pastoral; image-making and thought; reading Willa Cather to her grandmother in her Chicago apartment; the deviations of Walter Benjamin’s “scholarly romance,” The Arcades Project. Eisendrath’s wondrously woven hybrid work extols the materiality of reading, its pleasures and delights, with wild leaps and abounding grace.

“Rite of Passage” — Sharon Olds

Parsifal III — Anselm Kiefer

Parsifal III, 1973 by Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945)

Paul Kirchner’s Dope Rider: A Fistful of Delirium (Book acquired, 7 April 2021)

I am a huge fan of Paul Kirchner’s bold and witty comix. I fell in love with his cult strip The Bus some years back, and was thrilled when he revised the series with The Bus 2. Both volumes were published in handsome editions by the fine folks at Tanibis. The French publisher also released a retrospective collection of Kirchner’s work to date, the essential compendium Awaiting the Collapse. Tanibis also published the collected Hieronymus & Bosch, strip, another entry in the cartoonists explosive output in the twentyteens.

Now, Tanibis has published A Fistful of Delirium, the recent adventures of the resurrected hero Dope Rider. Kirchner’s Dope Rider is a mystical skeleton weedslinger, a philosophical wanderer prone to surreal transformation. Our cowboy rides again here via the full-page full-color strips Kirchner ran in High Times from 2015-2020. Here’s Tanibis’s blurb:

Dope Rider is back in town! After a 30-year hiatus, Paul Kirchner brought back to life the iconic bony stoner whose first adventures were a staple of the psychedelic counter-culture magazine High Times in the 1970s.

The stories collected in this book appeared in High Times between January 2015 and May 2020. Despite the years, Dope Rider has stayed essentially the same, still smoking his ever-present joint, getting high and chasing metaphysical dragons through whimsical realities in meticulously illustrated and colorful one-page adventures. Fans of the original Dope Rider comics will still find the bold graphical innovations, dubious puns and wild dreamscapes inspired by classical painting and western movies that were some of Dope Rider’s trademark.

This time though, Kirchner draws from a much larger panel of influences, including modern pop – and pot – culture (lines and characters from Star Wars as well as references to Denver as the US weed capital can be found here and there) and a wider range of artistic references, from Alice in Wonderland to 2001, A Space Odyssey to Ed Roth’s Kustom Kulture. Native American culture and mythology, only hinted at in the classic adventures, is also much more present in the form of Chief, one of Dope Rider’s new sidekicks. Kirchner’s playful, tongue-in-cheek humor binds together all these influences into stories that mock both the mundane and the nonsensical alike.

You can get a signed edition from Kirchner’s website. Full review down the line.

The Lobster — John Currin

The Lobster, 2001 by John Currin (b. 1962)

Careful Pretty — Helen Verhoeven

Careful Pretty, 2005 by Helen Verhoeven (b. 1974)

American Short Stories Since 1945 (Book published in 1968 and acquired, 30 April 2021)

I was perusing the anthologies, looking for a book called Anti-Story: An Anthology of Experimental Fiction (1971). I didn’t find it, but the spine of American Short Stories Since 1945 interested me enough to pull it out, and the wonderful cover (by Emanuel Schongut) intrigued me more. The tracklist on the back cover is what got to me:

I’ve read seven of the stories and fourteen of the twenty-six authors here. You probably have too. But there are close to a dozen authors here I’ll admit I’ve never even heard of—authors rectangle-pressed in with favorites of mine like Barthelme, Gass, Jackson, and Pynchon, whose piece “Under the Rose”is part of V., which I recently re-read. (I opened the “Acknowledgements” page to see that “Under the Rose” was first published in Noble Savage 3, May 1961—I checked the “N” anthologies and found Noble Savage #2, but no three for me.)

Edited and introduced by the poet John Hollander, Since 1945 “aims to show the major shapes taken by shorter fiction in America since the end of World War II.” Published in 1968, it’s heavy on the white guys, but I think there’s an attempt here to point toward not just “major shapes,” but new shapes.

I couldn’t not pick it up (I’d brought in some paperbacks to trade, anyway). Maybe I’ll try to read it this summer, posting on each piece. I’m most interested in how the selection of authors shows a tipping over in to postmodernism, a postmodernism many of these guys never signed up for.