The Belan Deck, Matt Bucher. SSMG Press (2023; second printing). Cover design by David Jensen. 119 pages.

Author: Biblioklept

“The Christmas Banquet” — Nathaniel Hawthorne

“The Christmas Banquet”

by

Nathaniel Hawthorne

In a certain old gentleman’s last will and testament there appeared a bequest, which, as his final thought and deed, was singularly in keeping with a long life of melancholy eccentricity. He devised a considerable sum for establishing a fund, the interest of which was to be expended, annually forever, in preparing a Christmas Banquet for ten of the most miserable persons that could be found. It seemed not to be the testator’s purpose to make these half a score of sad hearts merry, but to provide that the stern or fierce expression of human discontent should not be drowned, even for that one holy and joyful day, amid the acclamations of festal gratitude which all Christendom sends up. And he desired, likewise, to perpetuate his own remonstrance against the earthly course of Providence, and his sad and sour dissent from those systems of religion or philosophy which either find sunshine in the world or draw it down from heaven.

The task of inviting the guests, or of selecting among such as might advance their claims to partake of this dismal hospitality, was confided to the two trustees or stewards of the fund. These gentlemen, like their deceased friend, were sombre humorists, who made it their principal occupation to number the sable threads in the web of human life, and drop all the golden ones out of the reckoning. They performed their present office with integrity and judgment. The aspect of the assembled company, on the day of the first festival, might not, it is true, have satisfied every beholder that these were especially the individuals, chosen forth from all the world, whose griefs were worthy to stand as indicators of the mass of human suffering. Yet, after due consideration, it could not be disputed that here was a variety of hopeless discomfort, which, if it sometimes arose from causes apparently inadequate, was thereby only the shrewder imputation against the nature and mechanism of life. Continue reading ““The Christmas Banquet” — Nathaniel Hawthorne”

Comic as Christmas | From William H. Gass’s Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife

From William H. Gass’s Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife, as published as a supplement in a 1967 issue of TriQuarterly.

“A Chthonian Christmas” — Edward Gorey

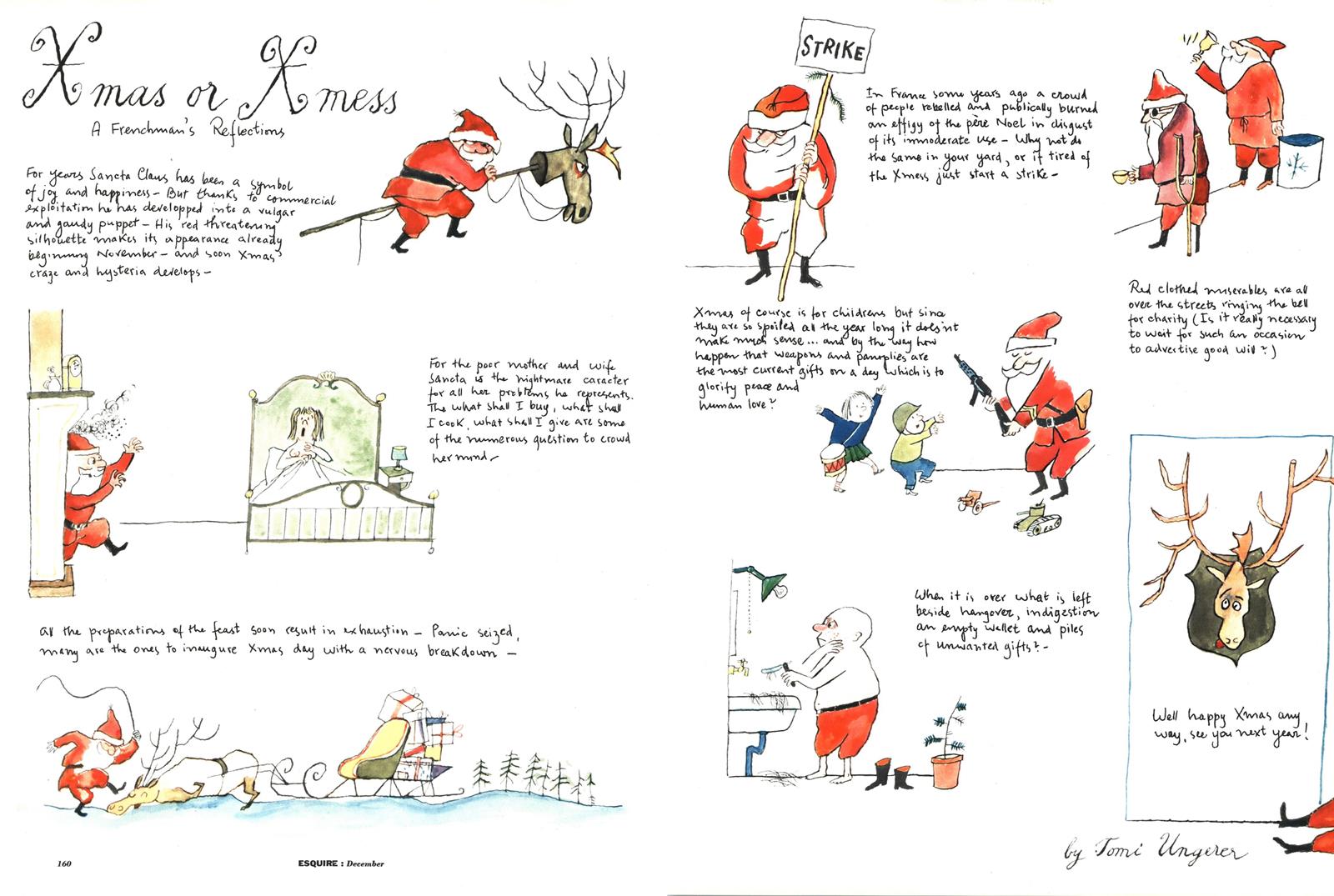

Xmas or Xmess — Tomi Ungerer

Read “Nackles,” Donald E. Westlake’s horror story about the Anti-Claus

“Nackles”

by

Donald E. Westlake

Did God create men, or does Man create gods? I don’t know, and if it hadn’t been for my rotten brother-in-law the question would never have come up. My late brother-in-law? Nackles knows.

It all depends, you see, like the chicken and the egg, on which came first. Did God exist before Man first thought of Him, or didn’t He? If not, if Man creates his gods, then it follows that Man must create the devils, too.

Nearly every god, you know, has his corresponding devil. Good and Evil. The polytheistic ancients, prolific in the creation (?) of gods and goddesses, always worked up nearly enough Evil ones to cancel out the Good, but not quite. The Greeks, those incredible supermen, combined Good and Evil in each of their gods. In Zoroaster, Ahura Mazda, being Good is ranged forever against the Evil one, Ahriman. And we ourselves know God and Satan.

But of course it’s entirely possible I have nothing to worry about. It all depends on whether Santa Claus is or is not a god. He certainly seems like a god. Consider: He is omniscient; he knows every action of every child, for good or evil. At least on Christmas Eve he is omnipresent, everywhere at once. He administers justice tempered with mercy. He is superhuman, or at least non-human, though conceived of as having a human shape. He is aided by a corps of assistants who do not have completely human shapes. He rewards Good and punishes Evil. And, most important, he is believed in utterly by several million people, most of them under the age of ten. Is there any qualification for godhood that Santa Claus does not possess?

And even the non-believers give him lip-service. He has surely taken over Christmas; his effigy is everywhere, but where are the manger and the Christ child? Retired rather forlornly to the nave. (Santa’s power is growing, too. Slowly but surely he is usurping Chanukah as well.)

Santa Claus is a god. He’s no less a god than Ahura Mazda, or Odin, or Zeus. Think of the white beard, the chariot pulled through the air by a breed of animal which doesn’t ordinarily fly, the prayers (requests for gifts) which are annually mailed to him and which so baffle the Post Office, the specially-garbed priests in all the department stores. And don’t gods reflect their creators’ society? The Greeks had a huntress goddess, and gods of agriculture and war and love. What else would we have but a god of giving, of merchandising, and of consumption? Secondary gods of earlier times have been stout, but surely Santa Claus is the first fat primary god.

And wherever there is a god, mustn’t there sooner or later be a devil?

Which brings me back to my brother-in-law, who’s to blame for whatever happens now. My brother-in-law Frank is – or was – a very mean and nasty man. Why I ever let him marry my sister I’ll never know. Why Susie wanted to marry him is an even greater mystery. I could just shrug and say Love is Blind, I suppose, but that wouldn’t explain how she fell in love with him in the first place.

Frank is – Frank was – I just don’t know what tense to use. The present, hopefully. Frank is a very handsome man in his way, big and brawny, full of vitality. A football player; hero in college and defensive line-backer for three years in pro ball, till he did some sort of irreparable damage to his left knee, which gave him a limp and forced him to find some other way to make a living.

Ex-football players tend to become insurance salesmen; I don’t know why. Frank followed the form, and became and insurance salesman. Because Susie was then a secretary for the same company, they soon became acquainted.

Was Susie dazzled by the ex-hero, so big and handsome? She’s never been the type to dazzle easily, but we can never fully know what goes on inside the mind of another human being. For whatever reason, she decided she was in love with him.

So they were married, and five weeks later he gave her her first black eye. And the last, though it mightn’t have been, since Susie tried to keep me from finding out. I was to go over for dinner that night, but at eleven in the morning she called the auto showroom where I work, to tell me she had a headache and we’d have to postpone the dinner. But she sounded so upset that I knew immediately something was wrong, so I took a demonstration car and drove over, and when she opened the front door there was the shiner.

I got the story out of her slowly, in fits and starts. Frank, it seemed, had a terrible temper. She wanted to excuse him because he was forced to be an insurance salesman when he really wanted to be out there on the gridiron again, but I want to be President and I’m an automobile salesman and I don’t go around giving women black eyes. So I decided it was up to me to let Frank know he wasn’t to vent his pique on my sister any more.

Unfortunately, I am five feet seven inches tall and weigh one hundred thirty-four pounds, with the Sunday Times under my arm. Were I just to give Frank a piece of my mind, he’d surely give me a black eye to go with my sister’s. Therefore, that afternoon I bought a regulation baseball bat, and carried it with me when I went to see Frank that night.

He opened the door himself and snarled, “What do you want?”

In answer, I poked him with the end of the bat, just above the belt, to knock the wind out of him. Then, having unethically gained the upper hand, I clouted him five or six times more, and then stood over him to say, “The next time you hit my sister I won’t let you off so easy.” After which I took Susie home to my place for dinner.

And after which I was Frank’s best friend.

People like that are so impossible to understand. Until the baseball bat episode, Frank had nothing for me but undisguised contempt. But once I’d knocked the stuffing out of him, he was my comrade for life. And I’m sure it was sincere; he would have given me the shirt off his back, had I wanted it, which I didn’t.

(Also, by the way, he never hit Susie again. He still had the bad temper, but he took it out on throwing furniture out windows or punching dents in walls or going downtown to start a brawl in some bar. I offered to train him out of maltreating the house and furniture as I had trained him out of maltreating his wife, but Susie said no, that Frank had to let off steam and it would be worse if he was forced to bottle it all up inside him, so the baseball bat remained in retirement.)

Then came the children, three of them in as many years. Frank Junior came first, and then Linda Joyce, and finally Stewart. Susie had held the forlorn hope that fatherhood would settle Frank to some extent, but quite the reverse was true. Shrieking babies, smelly diapers, disrupted sleep, and distracted wives are trials and tribulations to any man, but to Frank they were – like everything else in his life – the last straw.

He became, in a word, worse. Susie restrained him I don’t know how often from doing some severe damage to a squalling infant, and as the children grew toward the age of reason Frank’s expressed attitude toward them was that their best move would be to find a way to become invisible. The children, of course, didn’t like him very much, but then who did? Continue reading “Read “Nackles,” Donald E. Westlake’s horror story about the Anti-Claus”

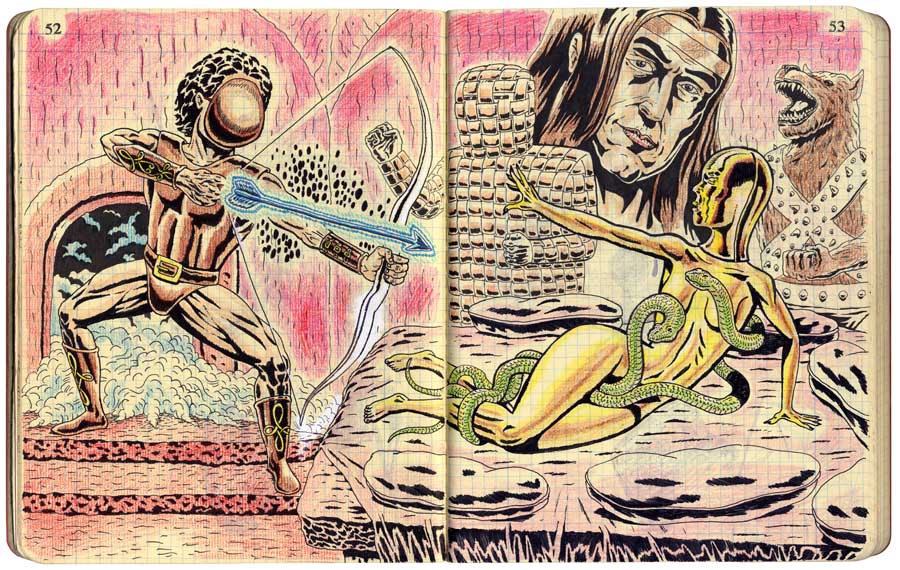

Untitled (Conquest) — Benjamin Marra

Untitled sketch (Conquest) by Benjamin Marra (b. 1977)

Antonio Di Benedetto’s The Suicides (Book acquired, 13 Dec. 2024)

I’m excited about this one. I loved the previous Antonio Di Benedetto novels I read, Zama (1956) and The Silentiary (1964), both also translated by Esther Allen. (I reviewed Zama here and The Silentiary here.)

The Suicides will publish in February 2025 from NYRB. Their blurb:

A stymied reporter in his early thirties embarks on an investigation of three unconnected suicides. All he has to go on are photos of the faces of the dead. Other suicides begin to proliferate, while a colleague in the archives sends him historical justifications of self-murder by thinkers of all sorts: Diogenes, David Hume, Emile Durkheim, Margaret Mead. His investigation becomes an obsession, and he finds himself ever more attracted to its subject as it proceeds.

The Suicides is the third volume of Antonio Di Benedetto’s Trilogy of Expectation, a touchstone for Roberto Bolaño and deemed “one of the culminating moments of twentieth-century fiction” by Juan José Saer. Following Zama (set during the eighteenth century) and The Silentiary (set during the 1950s), this final work takes place in a provincial city in the late 1960s, as Argentina plummets toward the “Dirty War.”

“Daily Reviewer-Haupt” — David Markson

More New Cult Canon

15. Battle Royale, Kinji Fukasaku (2000)

I actually rewatched Battle Royale just the other week. In retrospect, it’s difficult to assess the film against the influence it’s had, especially on video games. In his 2008 New Cult Canon entry, Scott Tobias described the film as “Lord Of The Flies meets The Most Dangerous Game meets perhaps the cruelest year of teenage life.” I think what many of us remember about Battle Royale is first the concept, so widely imitated, and then the violence—but it’s actually a gentler film, with hints of Rebel without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955). It’s also kinda goofy and disjointed.

6/10

Alternate: I don’t think they’re widely available as legal streams, but you could track down Kinji Fukasaku’s early 1970’s crime films, the Battles without Honor or Humanity series.

Alternate alternate: 10 minutes of Friedkin on Fukasaku:

16. Dead Man, Jim Jarmusch (1995)

A perfect film, one that seems better every time I see it. Gary Farmington is amazing as William Blake’s spiritual guide (“Stupid fucking white man” is a sublime line reading), and Jarmusch has a loaded bench to bounce pretty boy Depp off of (Iggy Pop is particularly scary, but Robert Mitchum seems an embodiment of evil from a truly different time—magnificent).

10/10

Alternate: El Topo, Alejandro Jodorowsky (1970)

17. Wet Hot American Summer, David Wain (2001)

I have no idea if Wet Hot American Summer holds up well—I think I was always part of its intended audience, part of the tail end of the “Reagan-era latchkey kids who grew up watching” the kind of films Wain’s movie is—satirizing?—on television. I watched Wet Hot American Summer approximately 100 times in 2003; it was one of a handful of DVDs on repeat at my best friend’s childhood house, where my unemployed unstructured ass spent a few nights a week crashing. His folks were in the beginning of a (permanent) separation, and the house seemed to have been ceded to a loose configuration of a dozen or so of us. We’d drink tallboys on the beach, stumble in, and fall asleep to The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001) or Reign of Fire (Rob Bowman, 2002) or Human Nature (Michel Gondry, 2001) or Wet Hot American Summer. There were probably others, but those are the ones I remember.

10/10

Alternate: Porky’s, Roy Clark (1981)

18. The Boondock Saints, Troy Duffy (1999)

The Boondock Saints is a truly awful film. It is relentlessly stupid and when it is funny, it is funny by accident—except when Willem Dafoe’s charm takes over one of the scenes he’s chewing up. The viewer can almost sense Dafoe rewriting Duffy’s sketchy, shoddy, nonsensical script in real time. For all its retrograde bluster (and poor filmmaking), The Boondock Saints actually has a viewpoint.

3/10

Alternate: Payback, Brian Helgeland (1999)

19. Punch-Drunk Love, Paul Thomas Anderson (2002)

Another perfect film. In his original New Cult Canon, Tobias suggested that,

Punch-Drunk Love marked the moment when Anderson threw away the stylistic

crutches of forbears like Martin Scorsese and Robert Altman, and came into his

own as an original filmmaker. That doesn’t mean he’s discarded these and other

influences altogether, which isn’t something he could or would want to do. But Punch-Drunk

Love has a unique texture that’s unmistakably Anderson’s, marked by a wired, coked-up

intensity and a yen for discord. It’s a film that sets viewers on edge from the

start, almost daring you not to like it.

Philip Seymour Hoffman might have stolen the film from Sandler, had he been in it more than the few minutes he’s actually on screen (he’s looming larger in our memory, as always).

10/10

Alternate: Popeye, Robert Altman (1980)

20. Wild Things, John McNaughton (1998)

This is another film that I watched because Tobias wrote about it. I had actually seen McNaughton’s film Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer entirely by mistake at a “party”; this probably happened around the same time that Wild Things released to theaters. But I never would have connected the two. I thought Wild Things was a different kind of trash than the trash it actually is. Tobias’s write-up makes an argument for Wild Things as high camp, a film told entirely within a set of quotation marks. I think he’s a bit too generous in his admiration for McNaughton’s film, but I ultimately enjoyed it.

6/10

Alternate: Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, Werner Herzog (2009)

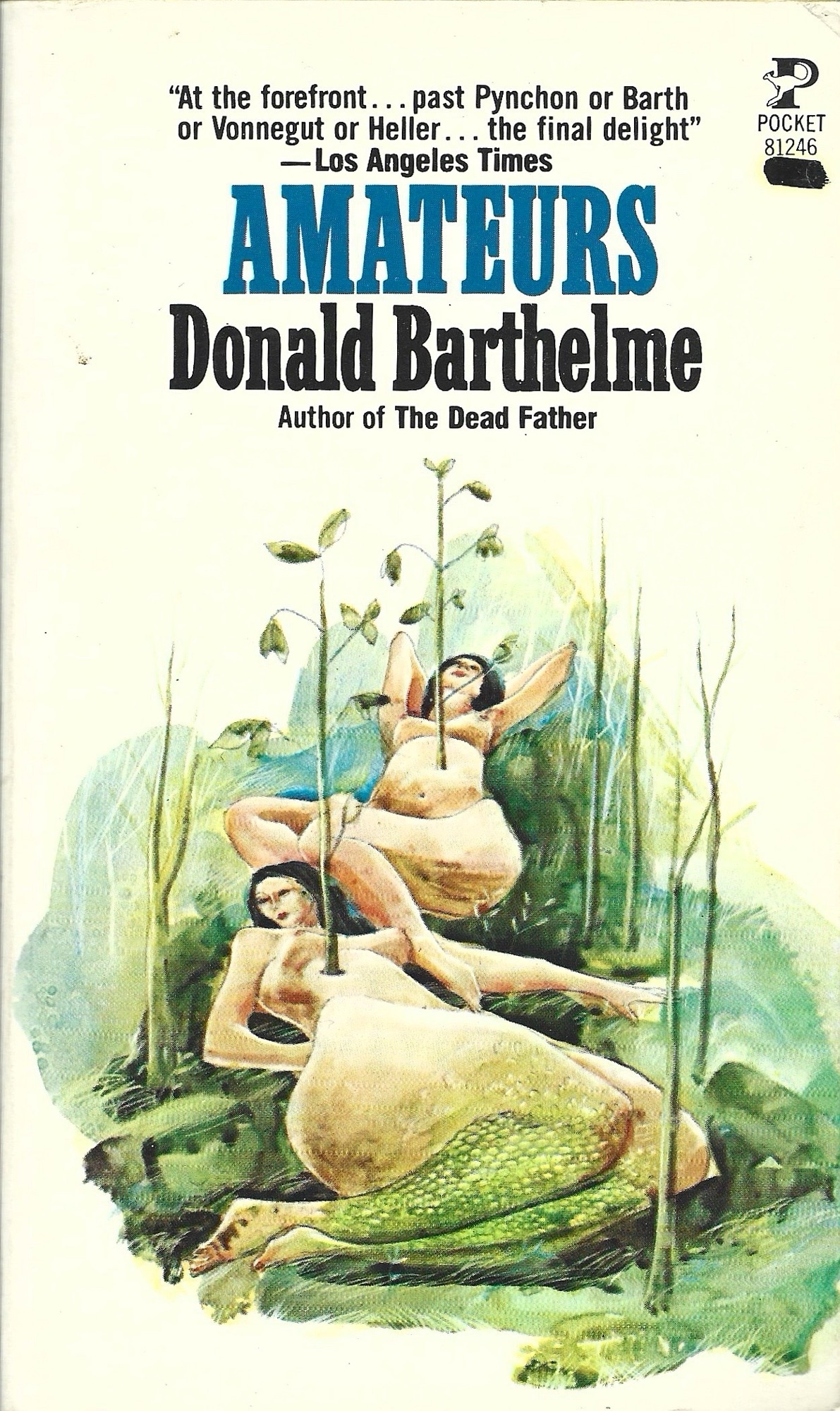

Mass-Market Monday | Donald Barthelme’s Amateurs

Amateurs, Donald Barthelme. Kangaroo Pocket Books (1977). No cover artist or designer credited. 207 pages.

I’ve written a few times about my slow acquisition of someone else’s library. This person lives in Perry, Florida, a small panhandle town south of Tallahassee, and I guess he drives into Jacksonville at least once a year to sell books at the bookstore I frequent. I’ve talked to the bookstore’s owner about him a few times. Sometimes, I’ll spot a spine and think, Yeah, his name and address are going to be stamped on the inside cover. And there it was this Friday when I picked up his mass-market edition of Amateurs. His by-now familiar habit of checking off volumes by the same author is on display here too. He also put neat pencil dashes by some of the stories in Amateurs, including my favorite from the collection, “Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby.” He also checked off “The Educational Experience,” which, in this Kangaroo edition of Amateurs, sadly fails to include Barthelme’s collage illustrations that accompanied the piece when it first ran in Harper’s

Continue reading “Mass-Market Monday | Donald Barthelme’s Amateurs”

Dec. 16th (Peanuts)

“The Hatchet Job” by José Lezama Lima, from The Death of Trotsky as Described by Various Cuban Writers, Several Years After the Event—or Before | From G. Cabrera Infante’s Novel Three Trapped Tigers

A chapter from Three Trapped Tigers

by G. Cabrera Infante

translated by Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine with collaboration by Infante

THE DEATH OF TROTSKY AS DESCRIBED BY VARIOUS CUBAN WRITERS, SEVERAL YEARS AFTER THE EVENT—OR BEFORE

THE HATCHET JOB

Legend has it that the stranger didn’t ask where he might eat or drink, but only where he could find the house with the adobe wall around it; and that, without so much as shaking the dust of his journey off both his feet, he made for his destination, which was the last retreat of Leon Son-of-David Bronstein: the prophet of that new-time religion who was to become the eponymous founder of its first heresy: messiah, apostle and heretic in one. The traveler, one Jacob Mornard, warped and twisted, and accompanied only by his seafaring hatred, had finally arrived in the notorious sanctuary of the Exile whose family name means stone of bronze and whose frank, fiery features were those of a rebellious rabbi. Furthermore, the old man was distinguished by his haughty and farsighted gaze underneath his horn-rimmed glasses; his oratorical gestures—like those of the men of the Greek agora not of the Hebrew agora; his woolly and knitted brows; and his sonorous voice, which usually reveals to ordinary mortals those whom the Fates have destined, from the cradle, to profound eloquences: all this and his goatee gave the New Wandering Jew a biblical countenance.

As for the future magnicide: his troubled appearance and the awkward gait of the born dissident were sketches of a murderous character which would never, in the dialectic mind of the assassinated Sadducee, find completion to cast, in the historical mold of a Cassius or even a Brutus, the low relief of an infamous persona.

Soon they were master and disciple; and while the noble and hospitable expatriate forgot his worries and afflictions, and allowed affection to blaze a trail of warmth in a heart that had anciently been frozen with reserve, his felonious follower seemed to carry in the stead of a heart something empty and nocturnal, a black void in which the slow, sinister and tenacious fetus of the most ignoble treachery was able to take roots and strike. Or perhaps, perchance it was a mean cunning that looked for revenge; because they say that at the back of his eyes he always carried a secret resentment against that man whom, with faultless subterfuge, he was in the habit of calling Master, using the capital letter that is reserved only for total obedience.

On occasions they could be seen together and although the good Lev Davidovich—we can call him that now, I suspect, even if in his lifetime he concealed with an initial this middle name that spelled yarmulke, and carried false credentials—took extreme precautions—because there were not lacking, as in the previous Roman tragedy, evil omens, the revelatory imagery of premonitions, or the ever-present habit of foreboding—he always granted audience in solitude to the taciturnal visitor, who was at times, as on the day of misfortune, both adviser and supplicant. This crimson Judas carried in his pale hands the manuscript in which his treachery was patently written with invisible ink; and over his thin blueish and trembling body he wore a Macfarlane, which would, to any eye more given to conjecture and suspicion, have given him away on that suffocatingly hot Mexican evening: distrust was not the strong point of the Russian rebel: nor systematic doubt: nor ill will a force of habit: underneath the coat the crafty assailant carried a treacherous hoof-parer: the magnicidal adze: an ice pick: and under the ax was his soul of guided emissary of the new Czar of Russia.

The trusting heresiarch was glancing attentively over the pretended scriptures, when the hatchet man of the Party delivered his treacherous blow and the steely shaft bit deep into that most noble head.

A cry resounded through the cloistered precincts and the sbirri (Haití had refused to send her eloquent Negroes) ran there in great haste and eager to convert the assassin into a prisoner. The magnanimous Marxian still had time to advise: “Thou shalt not kill,” and his inflamed followers did not hesitate to respect his instructions to the hilt.

Forty-eight hours of hopes, tears and vigil the formidable agony of that luminous leader lasted, dying as he had lived: in struggle. Life and a political career were no longer his: in their stead glory and historical eternity belonged to him.

José Lezama Lima

(1912-1965)

More New Cult Canon

9. Pi, Darren Aronofsky (1998)

A few years ago, I wrote about seeing Aronofsky’s first feature Pi at the student union film theater my second semester of college. I loved it and the people I went to see it with hated it. Aronofsky’s most infamous film, Requiem for a Dream (2000) remains the all-time worst film-viewing experience of my life (close second is Dancer in the Dark, von Trier, 2000—which I also saw at that same student union).

7?/10

Alternate: mother!, Darren Aronofsky, 2018

10. The Blair Witch Project, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez (1999)

Another artifact from my undergrad days. I am sure that I would be embarrassed to watch this one again, but at the time, it seemed really vital, definitely something new and different. I was taking a class which I think was called something like “electracy,” a course on “electronic literacy,” with Greg Ulmer. He showed us a bunch of Talking Heads videos I’m guessing everyone had already seen and tried to explain them, like a maniac.

We had to make two websites that semester. My first website was excellent—it was based on The Dakota building in Manhattan–John Lennon, Rosemary’s Baby, evil, the Nazis, Oprah Winfrey—it was a mess but I think it was one of the best things I’ve ever done. I got a B- on it and decided Ulmer was full of shit. I made the second website on The Blair Witch Project, an afterthought. It was stupid and I was embarrassed to submit it and I made an A. I still have the other site on a hard disk somewhere.

7?/10

Alternate: Rosemary’s Baby, Roman Polanski, 1968

11. I Am Cuba, Mikhail Kalatozov, 1964

I can’t muster anything real on this one. I vaguely recall getting it from our library, around the time it was “rediscovered” (Tobias writes about that in his New Cult Canon column). My big takeaway is that PT Anderson stole a great shot from the film (but not as great as the sequence he stole from Robert Downey’s Putney Swope).

7?/10

Alternate: Putney Swope, Robert Downey, 1969

12. The Rules of Attraction, Roger Avary, 2002

I still haven’t watched this one and Tobias’s write-up doesn’t make me want to. It might be good, even great, but I doubt I’ll ever know.

–?/10

Alternate: American Psycho, Mary Harron, 2000

13. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Shane Black, 2005

A fanfuckingtastic film (or maybe just a really, really fun film) that I think I wouldn’t have bothered to check out if not for Tobias’s column. Postmodernist techniques in film can come off as too-clever or simply exhausting, but Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is assured of story, assured of its audience, and assured that its faults are ultimately its charms. Great stuff.

9/10

Alternate: The Nice Guys, Shane Black 2016

14. Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control, Errol Morris, 1997

I don’t think Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control is actually a cult film. I mean, it might be, but I don’t think it is. I think it was a widely-available-on-VHS documentary feature in the late nineties, and I think that’s why I actually saw it then. I remember thinking it was Just Okay and then watching another half dozen Morris docs over the next 20 or so years and thinking that they were Just Okay.

Just Okay/10

Alternate: Literally any Werner Herzog film

Revisiting Scott Tobias’s The New Cult Canon

Today was the last meeting for a Tuesday-Thursday comp class that has been, or maybe I can now say had been, a fucking grind.

One bright spot was a student professing an interest in film. A few weeks ago he told me about watching Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925), and asked for recommendations. I rattled off titles, unsure how soaked he (and by extent, all) younger persons might be in (my notions of) the contemporary film canon. There are so many options now competing for eyeballs and earholes. We didn’t all grow up with our dad finishing a third beer and then insisting we stay up too late on a Sunday to catch the second half of For a Few Dollars More on the superstation. I suggested he work at checking off AFI’s “100 Years” list like I did back in circa 1998. “If something yanks at you, watch it again.”

But the kid wanted something stranger, and he followed up today. I rattled off titles, told him to email me, I’d send him a list, which he did, and then I did, send him a list that is — which was fun for me — and then I realized that I should really point him to film critic Scott Tobias’s series The New Cult Canon.

Back when the internet was still pretty good, Tobias wrote weekly column on a film he dared to place in his “New Cult Canon” — a continuation of film critic Danny Peary’s Cult Movies books. Tobias’s series ran at The AV Club (during the site’s glory years before capitalist hacks gutted it). Tobias’s New Cult Canon project intersected with an apparent wider access to films, whether it was your local library’s extensive DVD collection, Netflix sending you a disc through the USPS, or, y’know, internet piracy. Offbeat was now on the path, if you knew where to tread.

So for a few years, The New Cult Canon was a bit of a touchstone for me. It offered leads to new film experiences, made me revisit films I’d seen with an uncritical eye in the past through a new lens, and even aggravated with endorsements that I could never agree with. I loved The New Cult Canon column, and I was happy when Tobias revived it a few years ago on The Reveal.

But back to where I started, with the kid who wanted some film recommendations, wanted to immerse himself over the winter break (I’m pretty sure he used the verb immerse) — I didn’t follow up with an email to this link on IMDB of Tobias’s The New Cult Canon, which I’d to found to share with the kid who wanted some film recommendations–I started this blog instead.

As of now, there are 176 entries in The New Cult Canon. The first 162 were part of the series; original run at the AV Club. Coming across the original list this evening made me want to revisit the films, catch some of the ones I didn’t find or make time for before, and generally, like share.

The current media environment seems primed for ready-made cult movies. Film like, say, Late Night with the Devil (Cairnes, 2023) or Possessor (B. Cronenberg, 2020) are fun and compelling — but they also fit neatly into a specific market niche. (Where is the dad three beers deep who compels his youngan to stick it out with the second half of Under the Silver Lake (Mitchell, 2018)?

(If I review the previous paragraph, which I won’t, I’ll conclude I’m spoiled. Long live weird films.)

So let’s go:

Links on titles go to Tobias’s original write-ups. (I’d love to see a book of these.)

Arbitrary 0-10 score, based on How I Am Feeling At This Particular Moment.

The Alternate isn’t offered as a superior or inferior recommendation, just an alternate (unless it is offered as such).

I love Donnie Darko. I can’t remember how I first came across it, but I had the DVD and I would make people watch it. This kind of thing is maybe embarrassing to admit now; I think Donnie Darko hit a bad revisionist patch. Especially after Southland Tales and The Box.

When the director’s cut was released in theaters, sometime around 2005, I made some friends watch it with me in the theater. They fucking hated it.

I watched it with my son earlier this year and it was not nearly as weird as I’d remembered it and he enjoyed it and so did I. He got the E.T. reference and thought Patrick Swayze was a total creep.

8.5/10

Alternate: Southland Tales, Richard Kelly, 2006. (Look for the Cannes cut online.)

2. Morvern Callar, Lynne Ramsay, 2002

I knew about Morvern Callar because of its soundtrack (which was a totally legitimate way to know about a film two or three decades ago). I didn’t search Lynne Ramsay’s film out until after Tobias’s review.

This film made my stomach hurt and I never want to see it again. (Not a negative criticism.)

I feel the same way about the other two Ramsay films I’ve seen, We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and You Were Never Really Here (2017).

6.5/10

Alternate: You Were Never Really Here, Lynne Ramsay, 2017.

3. Irma Vep, Olivier Assayas, 1996

Minor fun, very French, ultimately ephemeral.

6/10

Alternate: Irma Vep, Olivier Assays, 2022 — an eight-episode HBO miniseries.

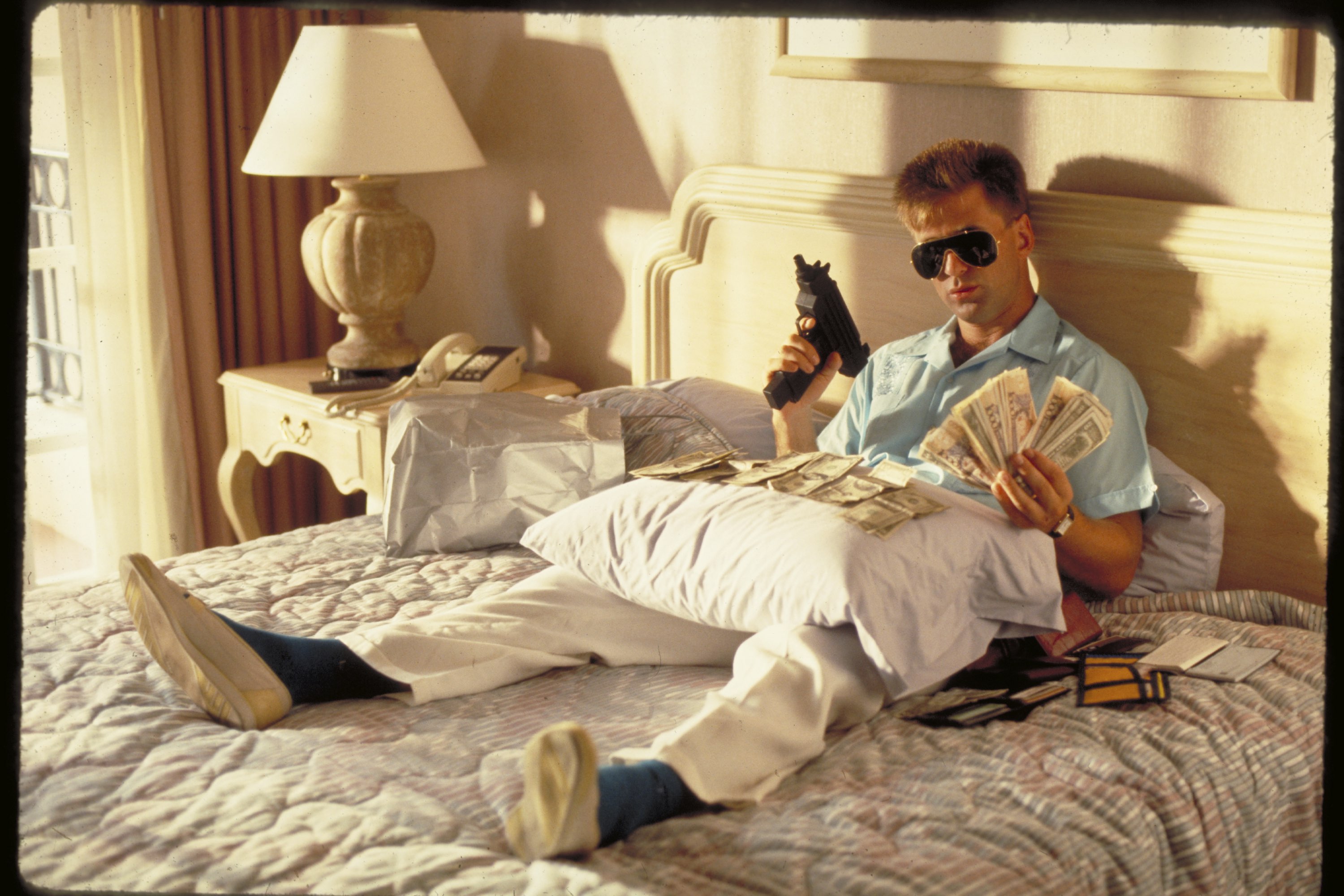

4. Miami Blues, George Armitage, 1990

Miami Blues is a very strange film. Except that it’s not strange: it’s a tonally-coherent, self-contained, “pastel-colored neo-noir,” as Tobias writes—but it feels like it comes from a different world. Alec Baldwin and Jennifer Jason Leigh seem, I dunno—skinnier? Is skinnier the right word?—here. The thickness of fame doesn’t stick to them so heavily. Miami Blues is fun but also mean-spirited, vicious even. It’s also the first entry on here that I would never have watched had it not been on Tobias’s recommendation.

7.5/10

Alternate: Grosse Pointe Blank, George Armitage, 1997

5. Babe: Pig in the City, George Miller, 1998

“Yeah, she thinks she’s Babe: Pig in the City.“

A perfect film.

10/10

Alternate: The Road Warrior, George Miller, 1981

6. They Live, John Carpenter, 1988

Another perfect movie, and one that only gets better with the years, through no fault of its own. They Live was certainly on the list I emailed the student. Roddy Piper (a rowdy man, by some accounts), also starred in Hell Comes to Frogtown (Donald G. Jackson and RJ Kizer, 1988) the same year, a very bad film, but also maybe a cult film.

10/10

Alternate: Like literally any John Carpenter film.

I hate and have always hated Clerks and every other Kevin Smith film I’ve seen. I remember renting it from Blockbuster my junior year of high school because of some stupid fucking write up in Spin or Rolling Stone and thinking it was bad cold garbage, not even warm garbage — poorly-shot, poorly-acted, unfunny. Even at (especially at?j sixteen, Smith’s vision of reality struck me as emotionally-stunted, stupid, etiolated, and even worse, dreadfully boring. I remember sitting through Chasing Amy and Dogma in communal settings, thinking, What the fuck is this cold, cold garbage?

But Tobias’s inclusion of Smith’s bad awful retrograde shit makes sense — Clerks spoke to a significant subset in the nineties, no matter how bad the film sucks.

0.5/10

Alternate: As Smith has never made an interesting film, let alone a good one, my instinct is to go to Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1990) — but that shows up later in the New Cult Canon. So, I dunno–a better film about friends and problematic weirdos: Ghost World, Terry Zwigoff, 2001

8. Primer, Shane Carruth (2004)

Let’s not end on a sour note.

I think that it was Tobias’s New Cult Canon series that hipped me to Primer, Shane Carruth’s brilliant lo-fi take on time travel. Carruth made the film for under ten grand, but it looks great and is very smart, and most of all, trusts its audience by throwing them into the deep end. (Primer is perhaps the inverse of Clerks. I hate that sentence, but I won’t delete it. They don’t belong in the same universe, these films; Primer builds its time machine out there!)

10/10

Alternate: Upstream Color, Shane Carruth, 2013

“The Story of a Stick (With Some Additional Comments by Mrs. Campbell),” a chapter from Three Trapped Tigers by G. Cabrera Infante

“The Story of a Stick (With Some Additional Comments by Mrs. Campbell)”

a chapter from Three Trapped Tigers

by G. Cabrera Infante

translated by Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine with collaboration by Infante

The Story

We arrived in Havana one Friday around three in the afternoon. The heat was oppressive. There was a low ceiling of dense gray, or blackish, clouds. As the boat entered the harbor the breeze that had cooled us off during the crossing suddenly died down. My leg was bothering me again and it was very painful going down the gangplank. Mrs. Campbell followed behind me talking the whole damned time and she found everything, but everything, enchanting: the enchanting little city, the enchanting bay, the enchanting avenue facing the enchanting dock. All I knew was that there was a humidity of 90 or 95 percent and that I was sure my leg was going to bother me the whole weekend. It was, of course, Mrs. Campbell’s brilliant idea to come to such a hot and humid island. I told her so as soon as I was on deck and saw the ceiling of rain clouds over the city. She protested, saying they had sworn to her in the travel agency that it was always, but always, spring in Cuba. Spring my aching foot! We were in the Torrid Zone. That’s what I told her and she answered, “Honey, this is the tropics!”

On the edge of the dock there was this group of enchanting natives playing a guitar and rattling some gourds and shouting infernal noises, the sort of thing that passes for music here. In the background, behind this aboriginal orchestra, there was an open-air tent where they sold the many fruits of the tropical tree of tourism: castanets, brightly painted fans, wooden rattlers, musical sticks, shell necklaces, earthenware pots, hats made of a brittle yellow straw and stuff like that. Mrs. Campbell bought one or two articles of every kind. She was simply enchanted. I told her she should wait till the day we left before making purchases. “Honey,” she said, “they are souvenirs.” She didn’t understand that souvenirs are what you buy when you leave a country. Nor was there any point in explaining. Luckily they were very quick in Customs, which was surprising. They were also very friendly, although they did lay it on a bit thick, if you know what I mean.

I regretted not bringing the car. What’s the point of going by ferry if you don’t take a car? But Mrs. Campbell thought we would waste too much time learning foreign traffic regulations. Actually she was afraid we would have another accident. Now there was one more argument she could throw in for good measure. “Honey, with your leg in this state you simply cannot drive,” she said. “Let’s get a cab.”

We waved down a taxi and a group of natives—more than we needed—helped us with our suitcases. Mrs. Campbell was enchanted by the proverbial Latin courtesy. It was useless to tell her that it was a courtesy you also pay for through your proverbial nose. She would always find them wonderful, even before we landed she knew everything would be just wonderful. When all our baggage and the thousand and one other things Mrs. Campbell had just bought were in the taxi, I helped her in, closed the door in keen competition with the driver and went around to the o

ther door because I could get in there more easily. As a rule I get in first and then Mrs. Campbell gets in, because it’s easier for her that way, but this impractical gesture of courtesy which delighted Mrs. Campbell and which she found “very Latin” gave me the chance to make a mistake I will never forget. It was then that I saw the walking stick.

It wasn’t an ordinary walking stick and this alone should have convinced me not to buy it. It was flashy, meticulously carved and expensive. It’s true that it was made of a rare wood that looked like ebony or something of that sort and that it had been worked with lavish care—exquisite, Mrs. Campbell called it—and translated into dollars it wasn’t really that expensive. All around it there were grotesque carvings of nothing in particular. The stick had a handle shaped like the head of a Negro, male or female—you can never tell with artists—with very ugly features. The whole effect was repulsive. However, I was tempted by it even though I have no taste for knickknacks and I think I would have bought it even if my leg hadn’t been hurting. (Perhaps Mrs. Campbell, when she noticed my curiosity, would have pushed me into buying it.) Needless to say Mrs. Campbell found it beautiful and original and—I have to take a deep breath before I say it—exciting. Women, good God!

We got to the hotel and checked in, congratulating ourselves that our reservations were in order, and went up to our room and took a shower. Ordered a snack from room service and lay down to take a siesta—when in Rome, etc. . . . No, it’s just that it was too hot and there was too much sun and noise outside, and our room was very clean and comfortable and cool, almost cold, with the air-conditioning. It was a good hotel. It’s true it was expensive, but it was worth it. If the Cubans have learned something from us it’s a feeling for comfort and the Nacional is a very comfortable hotel, and what’s even better, it’s efficient. When we woke up it was already dark and we went out to tour the neighborhood.

Outside the hotel we found a cab driver who offered to be our guide. He said his name was Raymond something and showed us a faded and dirty ID card to prove it. Then he took us around that stretch of street Cubans call La Rampa, with its shops and neon signs and people walking every which way. It wasn’t too bad. We wanted to see the Tropicana, which is advertised everywhere as “the most fabulous cabaret in the world,” and Mrs. Campbell had made the journey almost especially to go there. To kill time we went to see a movie we wanted to see in Miami and missed. The theater was near the hotel and it was new and air-conditioned.

We went back to the hotel and changed. Mrs. Campbell insisted I wear my tuxedo. She was going to put on an evening gown. As we were leaving, my leg started hurting again—probably because of the cold air in the theater and the hotel—and I took my walking stick. Mrs. Campbell made no objection. On the contrary, she seemed to find it funny.

The Tropicana is in a place on the outskirts of town. It is a cabaret almost in the jungle. It has gardens full of trees and climbing plants and fountains and colored lights along all the road leading to it. The cabaret has every right to advertise itself as fabulous physically, but the show consists—like all Latin cabarets, I guess—of half-naked women dancing rumbas and singers shouting their stupid songs and crooners in the style of Bing Crosby, but in Spanish. The national drink of Cuba is the daiquiri, a sort of cocktail with ice and rum, which is very good because it is so hot in Cuba—in the street I mean, because the cabaret had the “typical Cuban air-conditioning” as they call it, which means the North Pole encapsuled in a tropical saloon. There’s a twin cabaret in the open air but it wasn’t functioning that night because they were expecting rain. The Cubans proved good meteorologists. We’d only just begun to eat one of those meals they call international cuisine in Cuba, which consist of things that are too salty or full of fat or fried in oil which they follow with a dessert that is much too sweet, when a shower started pouring down with a greater noise than one of those typical bands at full blast. I say this to give some idea of the violence of the rainfall as there are very few things that make more noise than a Cuban band. For Mrs. Campbell this was the high point of sophisticated savagery: the rain, the music, the food, and she was simply enchanted. Everything would have been fine—or at any rate passable; when we switched to drinking whiskey and soda I began to feel almost at home—but for the fact that this stupid maricón of an emcee of the cabaret, not content with introducing the show to the public, started introducing the public to the show, and it even occurred to this fellow to ask our names—I mean all the Americans who were there—and he started introducing us in some godawful travesty of the English language. Not only did he mix me up with the soup people, which is a common enough mistake and one that doesn’t bother me anymore, but he also introduced me as an international playboy. Mrs. Campbell, of course, was on the verge of ecstasy! Continue reading ““The Story of a Stick (With Some Additional Comments by Mrs. Campbell),” a chapter from Three Trapped Tigers by G. Cabrera Infante”

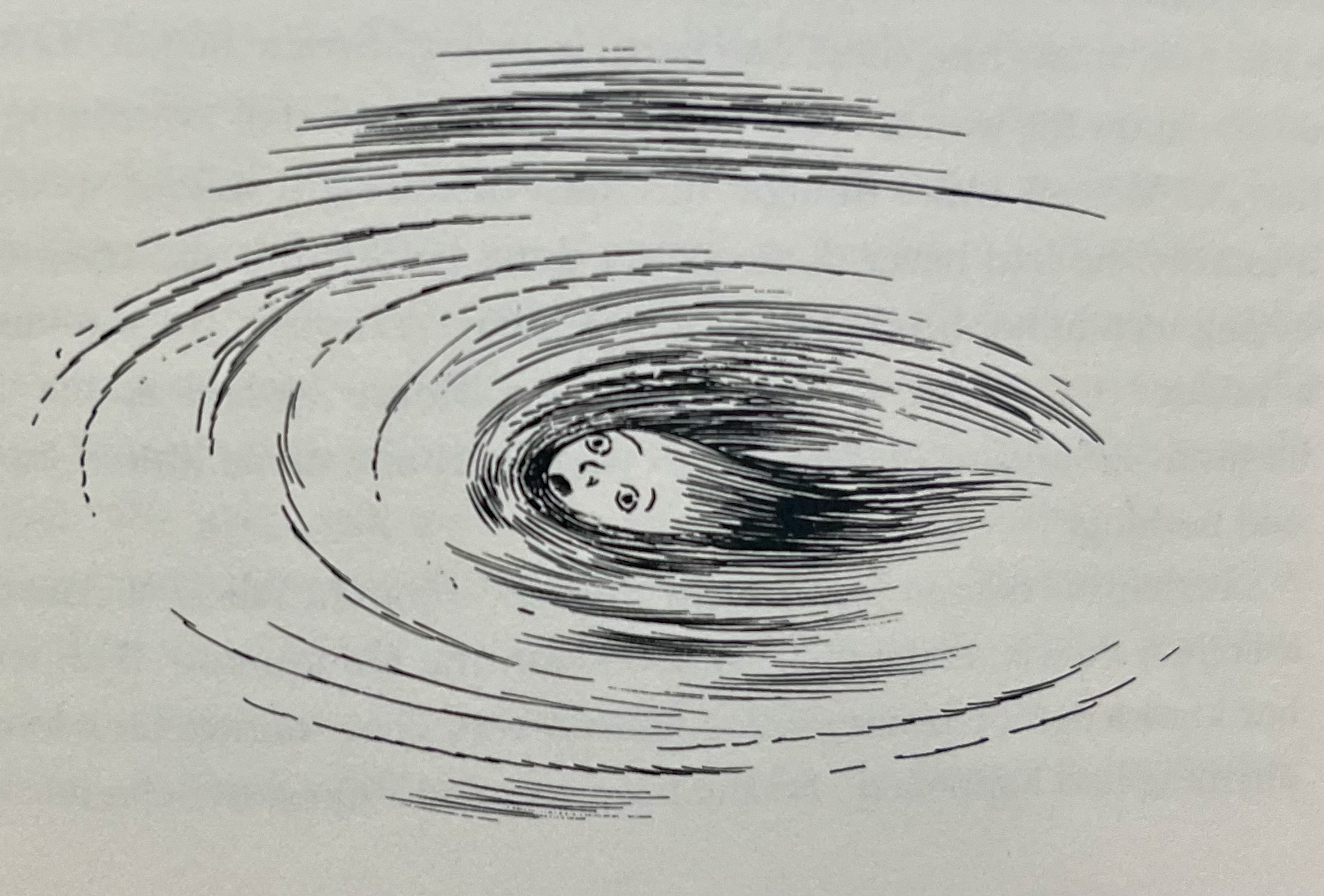

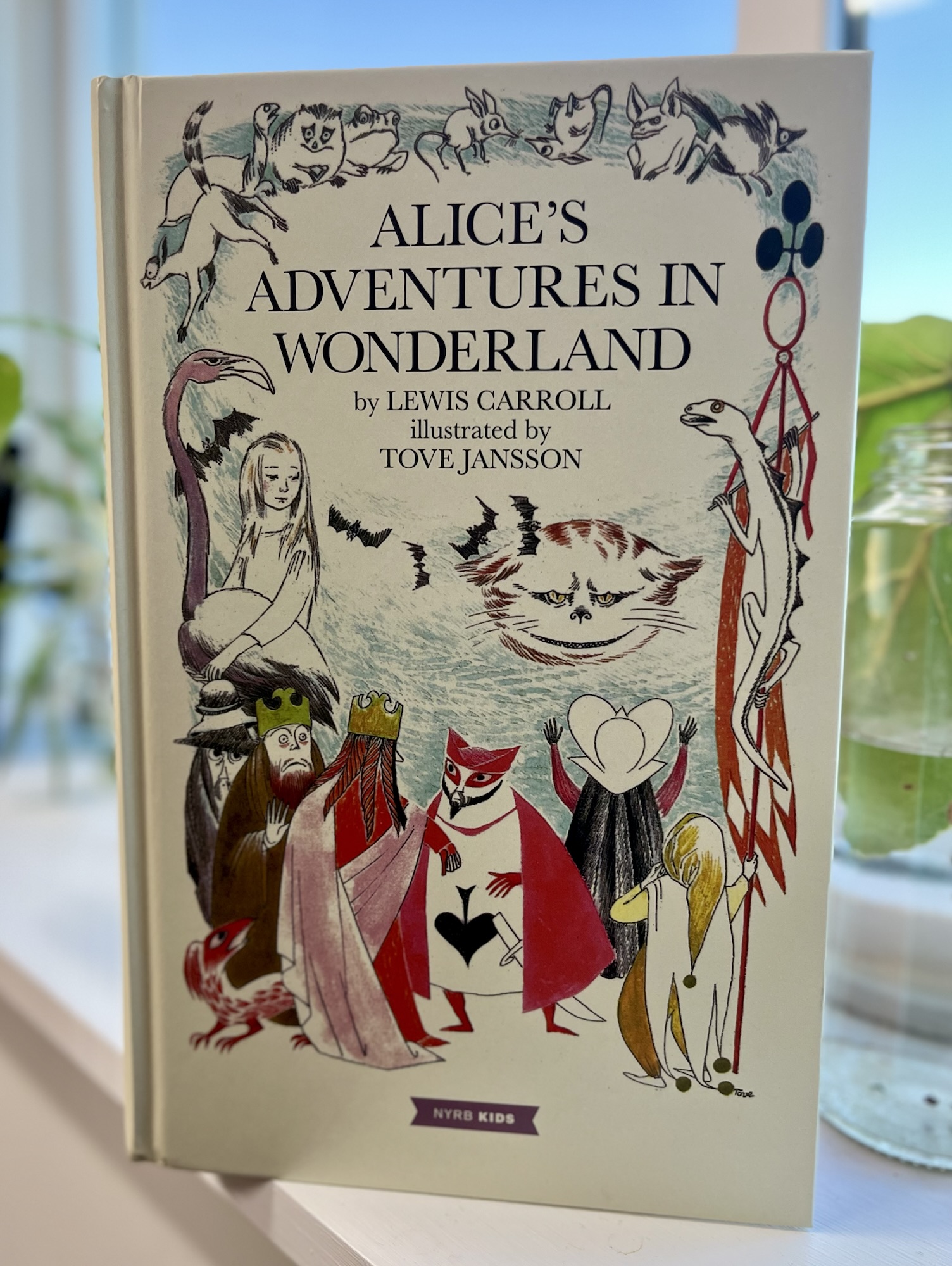

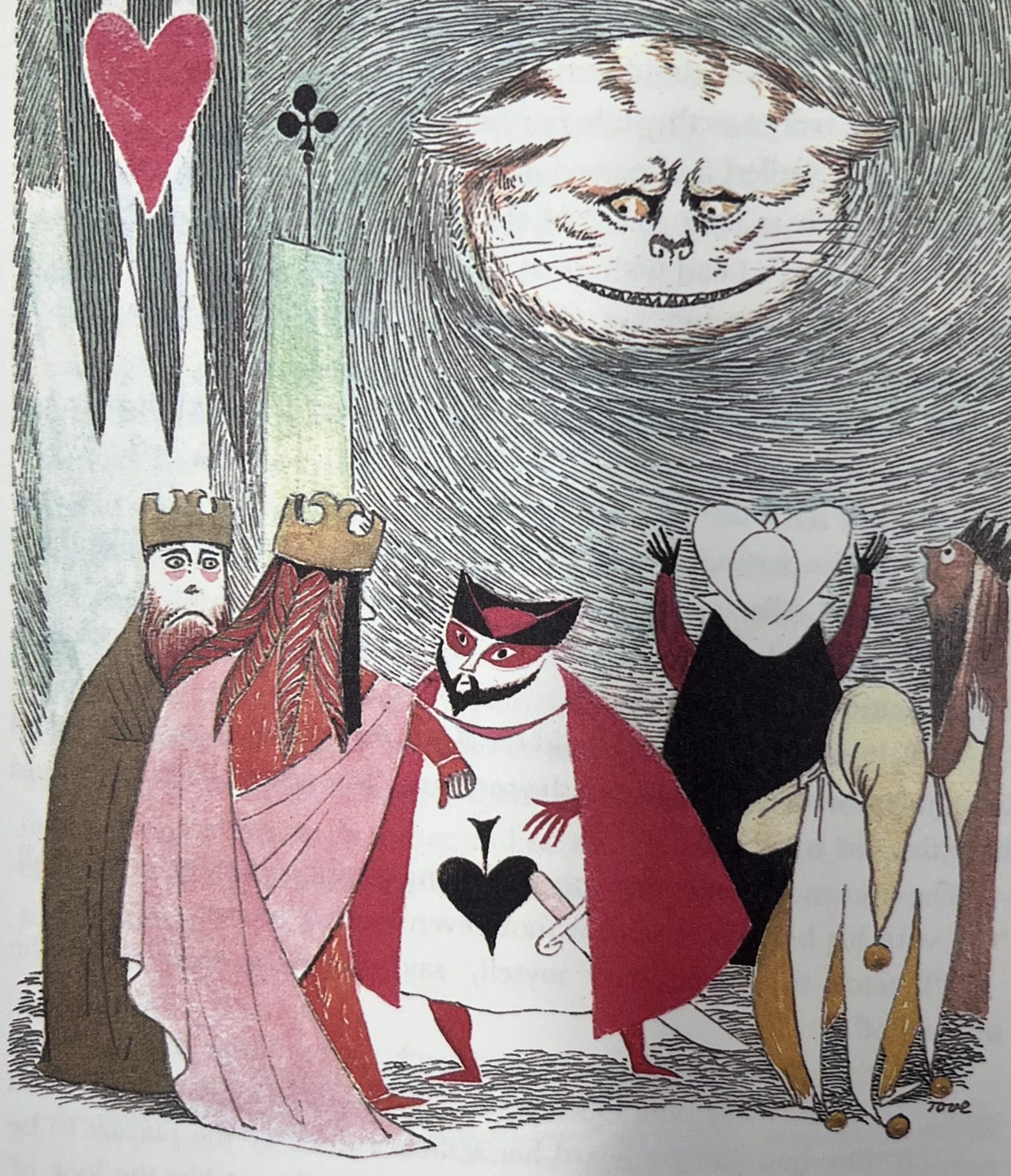

On Tove Jansson’s odd and touching illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

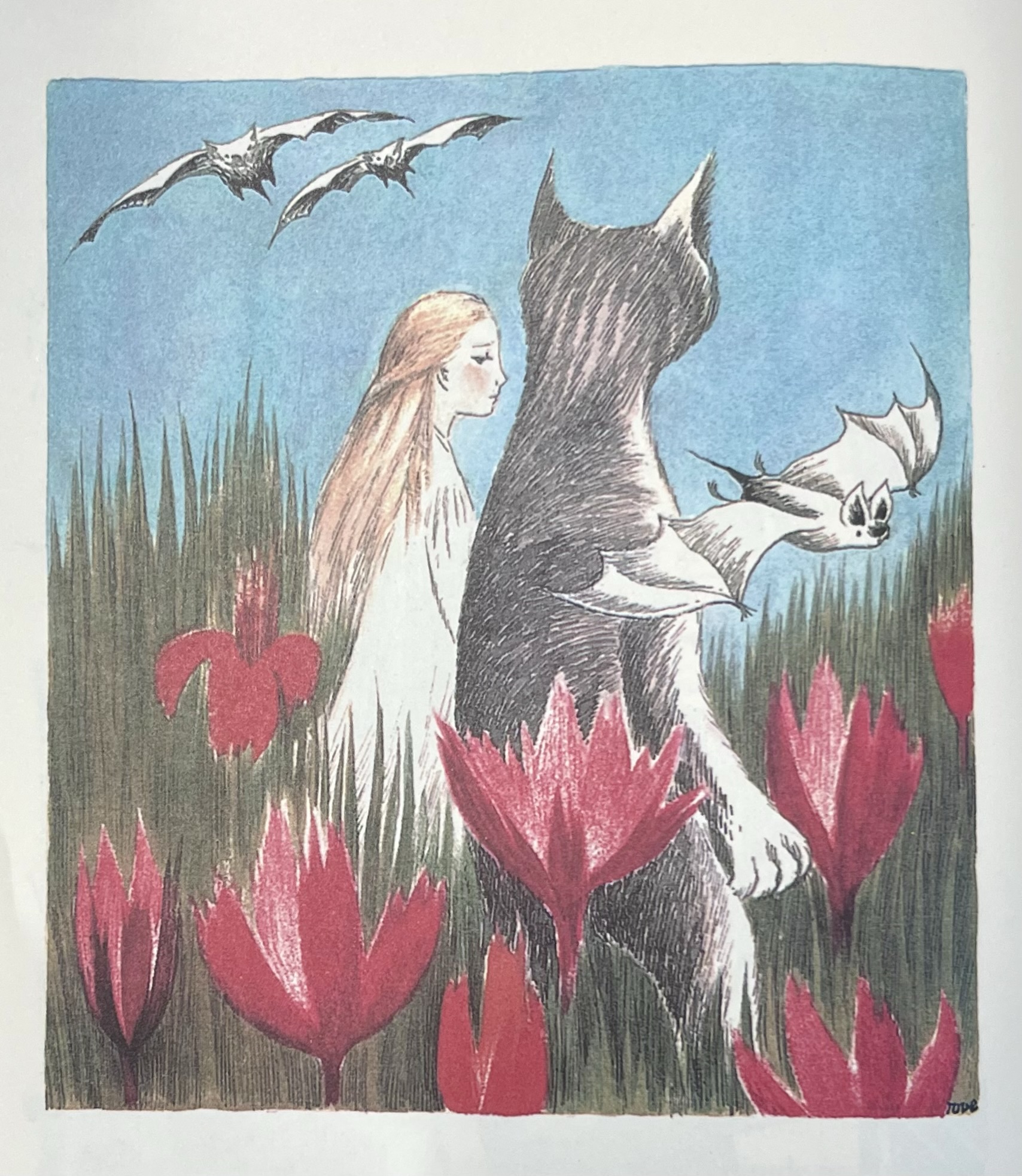

This fall–just in time for the holiday season–the NYRB Kids imprint has published an edition of Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland illustrated by the Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson. Jansson is most famous for her Moomin books, which remain an influential cult favorite with kids and adults alike. She illustrated Carroll’s Alice in 1966 for a Finnish audience; this NRYB edition is the first English-language version of the book. There are illustrations on almost every page of the book; most are black and white sketches — doodles, portraits, marginalia — but there are also many full-color full-pagers, like this odd image about a dozen pages in:

Here we have Alice and her cat Dinah, transformed into a shadowy, even sinister figure, large, bipedal. Bats float in the background, echoing Goya’s famous print El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. The image accompanies Alice’s initial descent into her underland wonderland: “Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again,” addressing Dinah, who will “miss me very much to-night, I should think!” Wonderlanding if Dinah might catch a bat, which is something like a mouse, maybe, “Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, ‘Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, ‘Do bats eat cats?; for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it.” Jansson’s red flowers suggest poppies, contributing to the scene’s slightly-menacing yet dreamlike vibe. The image ultimately echoes the myth of Hades and Persephone.

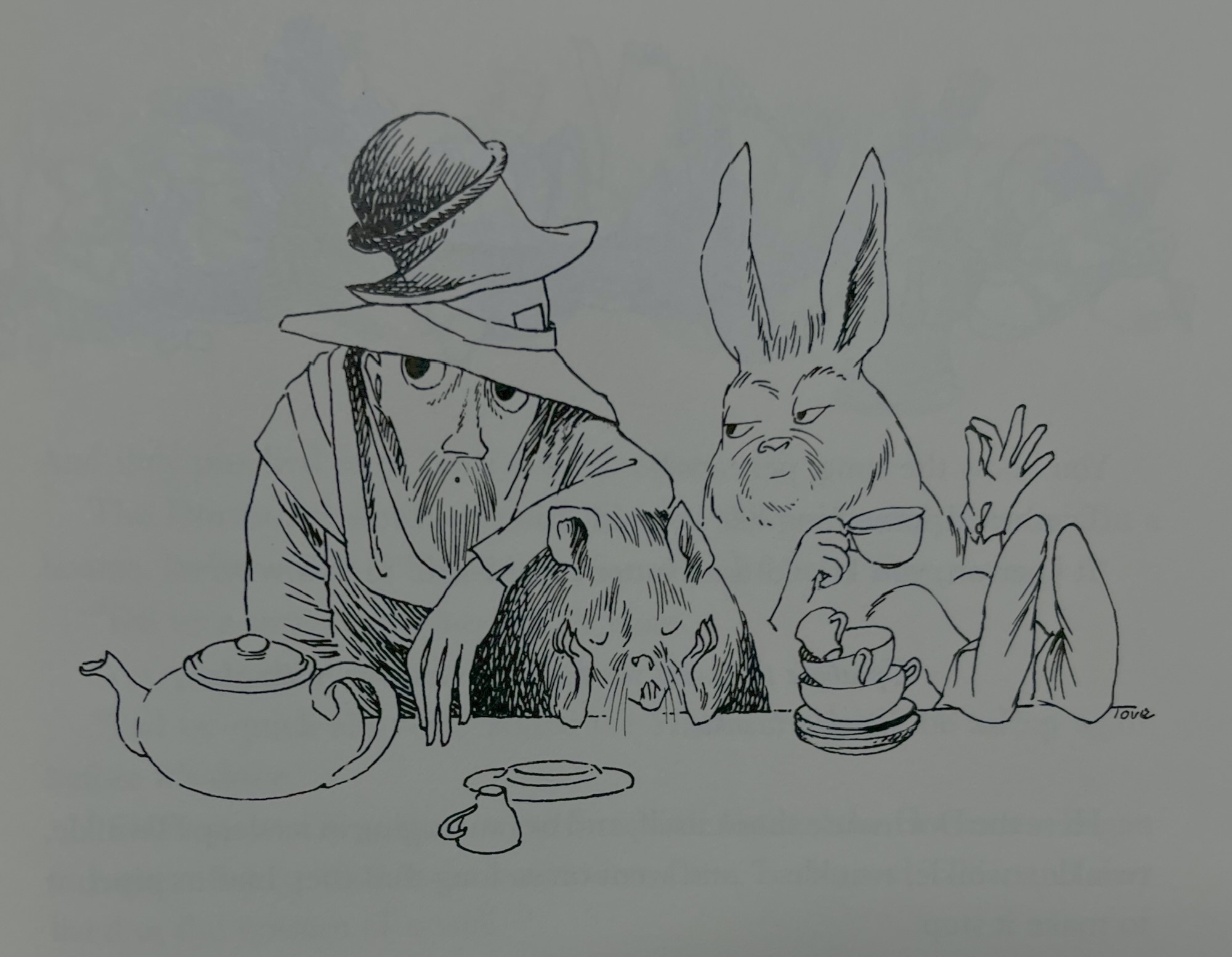

All the classic characters are here, of course, rendered in Jansson’s sensitive ink. Consider this infamous trio —

There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head.

I love Jansson’s take on the Hatter; he’s not the outright clown we often see in post-Disneyfied takes on the character, but rather a creature rendered in subtle pathos. The March Hare is smug; the Dormouse is miserable.

And you’ll want a glimpse of the famous Cheshire cat who appears (and disappears) during the Queen’s croquet match:

Jansson’s figures here remind one of the surrealist Remedios Varo’s strange, even ominous characters. Like Varo and fellow surrealist Leonora Carrington, Jansson’s art treads a thin line between whimsical and sinister — a perfect reflection of Carroll’s Alice, which we might remember fondly as a story of magical adventures, when really it is much closer to a horror story, a tale of being sucked into an underworld devoid of reason and logic, ruled by menacing, capricious, and ultimately invisible forces. It is, in short, a true reflection of childhood,m. Great stuff.