Clifford Mead’s Thomas Pynchon: A Bibliography was published in 1989 by Dalkey. As far as I can tell, the book is out of print and has not been updated.

I checked out Thomas Pynchon: A Bibliography via interlibrary loan back in early March, 2020. My librarian borrowed it for me from the good librarians at the University of South Florida. I can’t really recall why I wanted it—probably not anything specific. I’ve used ILL to get a number of weird or rare items in the past, including a pristine copy of Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confessions (a major source for Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian), and a handful of early stories by William Gaddis (I did not need to get my hands on this juvenalia).

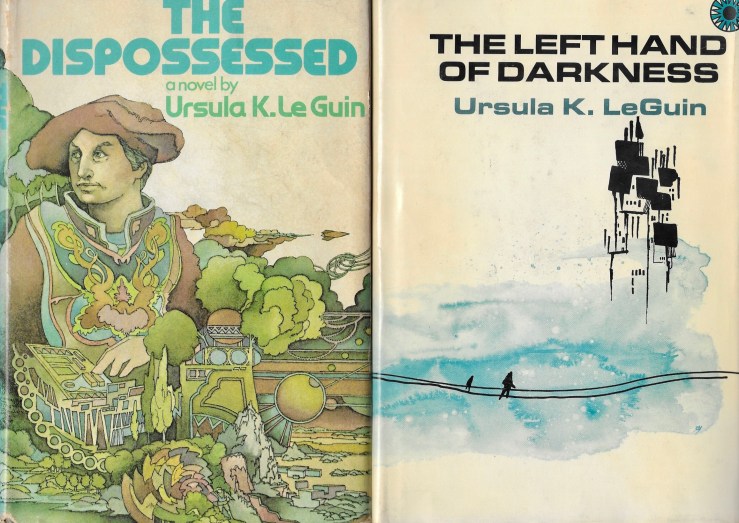

I probably got the bibliography on Tuesday, March 10, 2020. I think that’s the date because I tweeted this photo from its appendix:

If I recall correctly, I had taken that Monday (March 9th) and the preceding Friday off work. My family and I went to Georgia’s coastal Golden Isles and stayed on a houseboat for a few nights. It was the end of my kids’ spring break, and I would have a week of work before my spring break started.

This—the family vacation week—was the first week of March and I was beginning to get pretty paranoid about COVID-19. But I’d been paranoid and tired and really just exhausted for four years straight by now.

I took a break from Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy to read Charles Wright’s novel The Wig that weekend. I read it on a houseboat with a corny name on Jekyll Island. We rode bikes around the island and ate sea food, fried food. It was beautiful.

I came back to work, worried but happy to get the Pynchon bibliography, even if it only went to ’89, thus leaving out, like, the last three decades. That must have been, like I said, Tuesday, March 10th.

On Wednesday, March 11th, the NBA canceled their season and I knew what was up.

My department chair decorated our office suite with glittery shamrocks for the upcoming St. Patrick’s Day.

I filled a box with the books and binders and gear I figured I needed to teach from home after Spring Break. A colleague made a joke, something like a, Hey did you get fired with that box in your hands? joke.

(Maybe I’ll see him this fall?)

(Those St. Patrick’s Day decorations are still up, by the way, and, once again, out of season. Although I think they fit the mode of the day, the zeitgeist, the long tacky sparkling sad celebratory day.)

And you more or less know the rest, having lived it in your own first-person perspective.

For most of the year that passed I kept Thomas Pynchon: A Bilbiography with my textbooks. I reached out to my librarian around the time it was due, 10 May 2020 (my wife and I were supposed to be in Chicago then; we weren’t). My librarian said to keep the book in good condition.

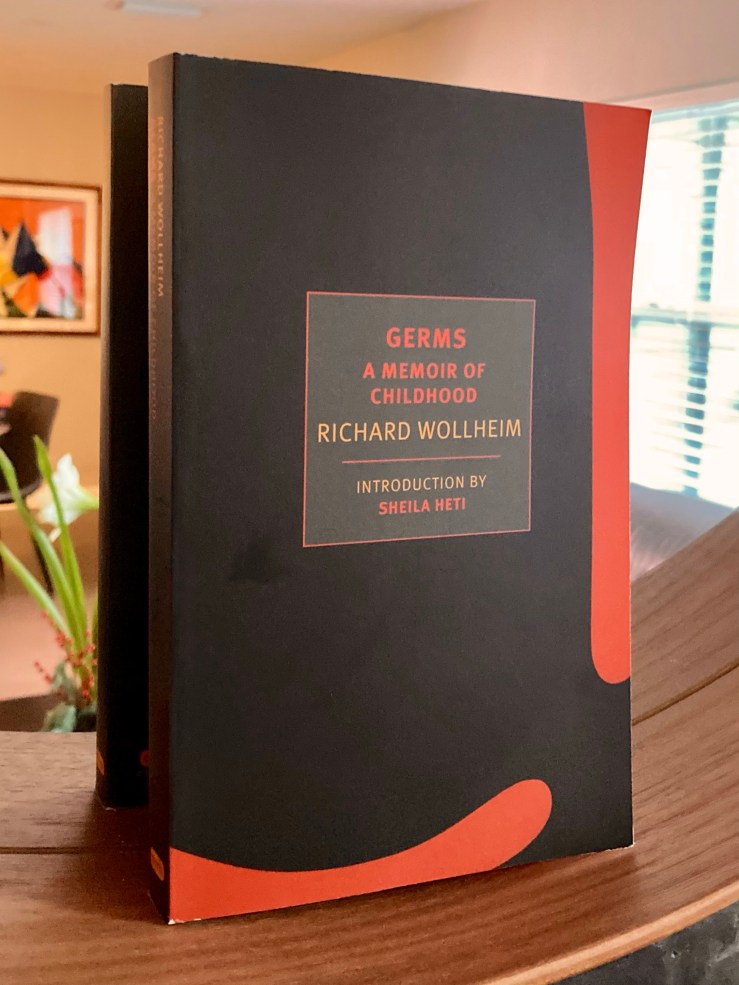

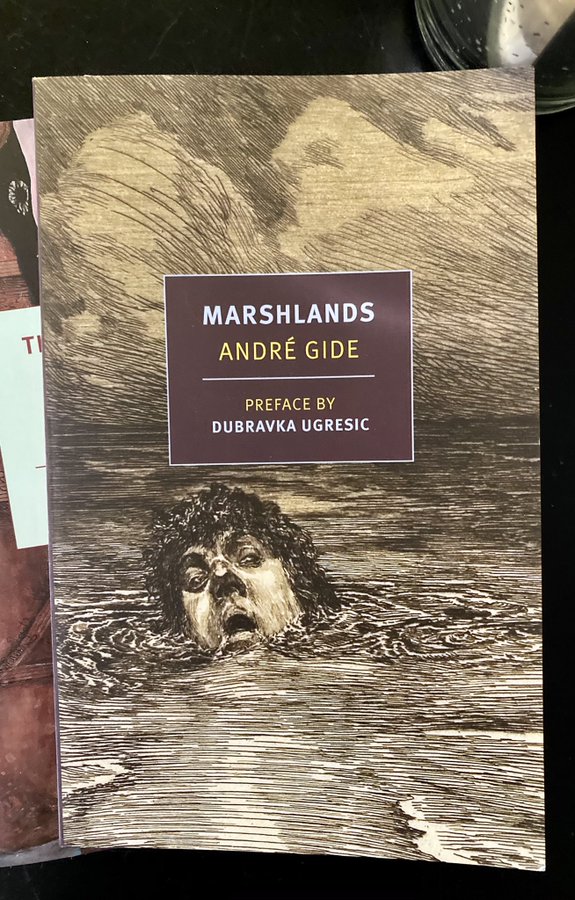

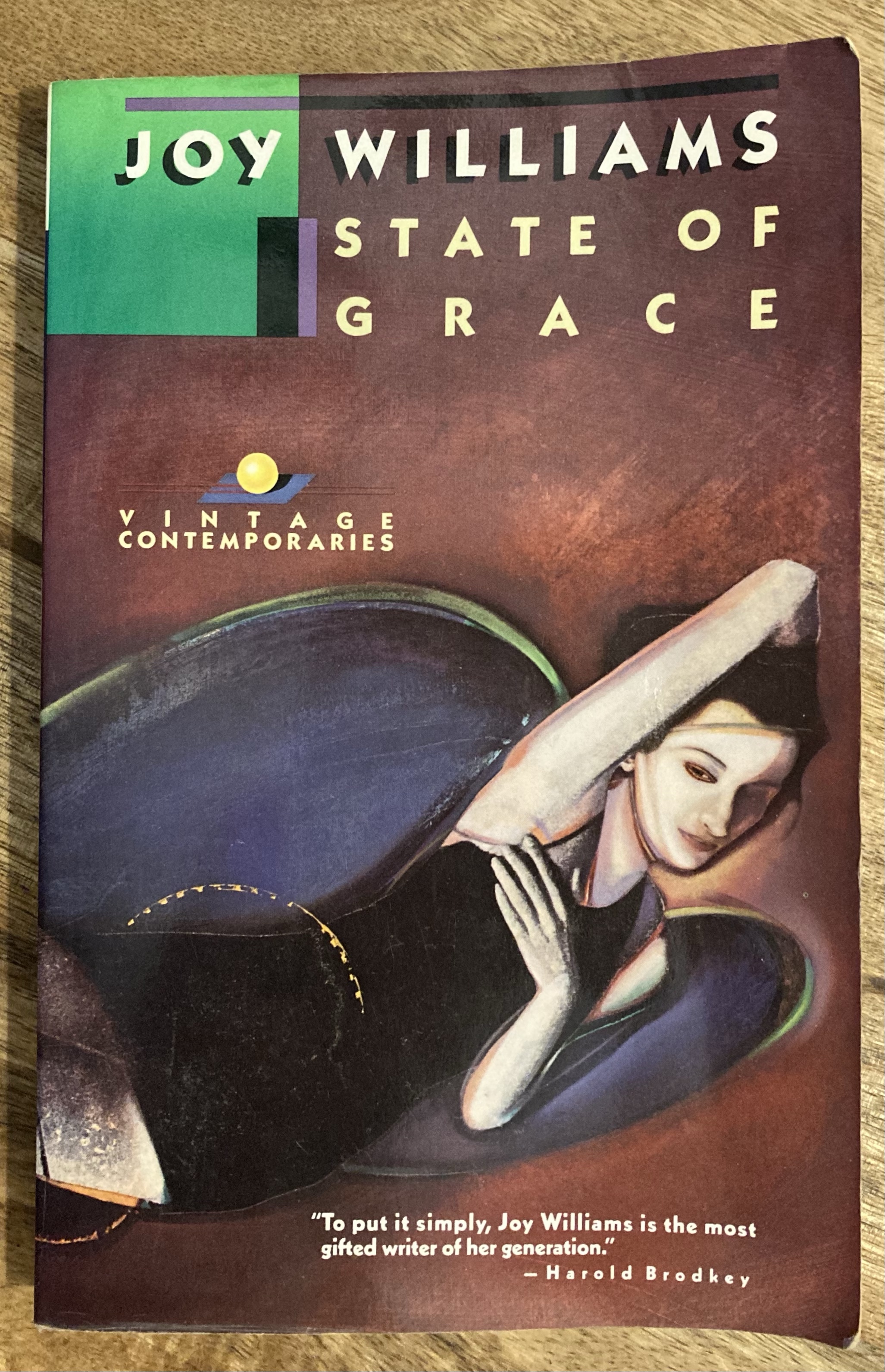

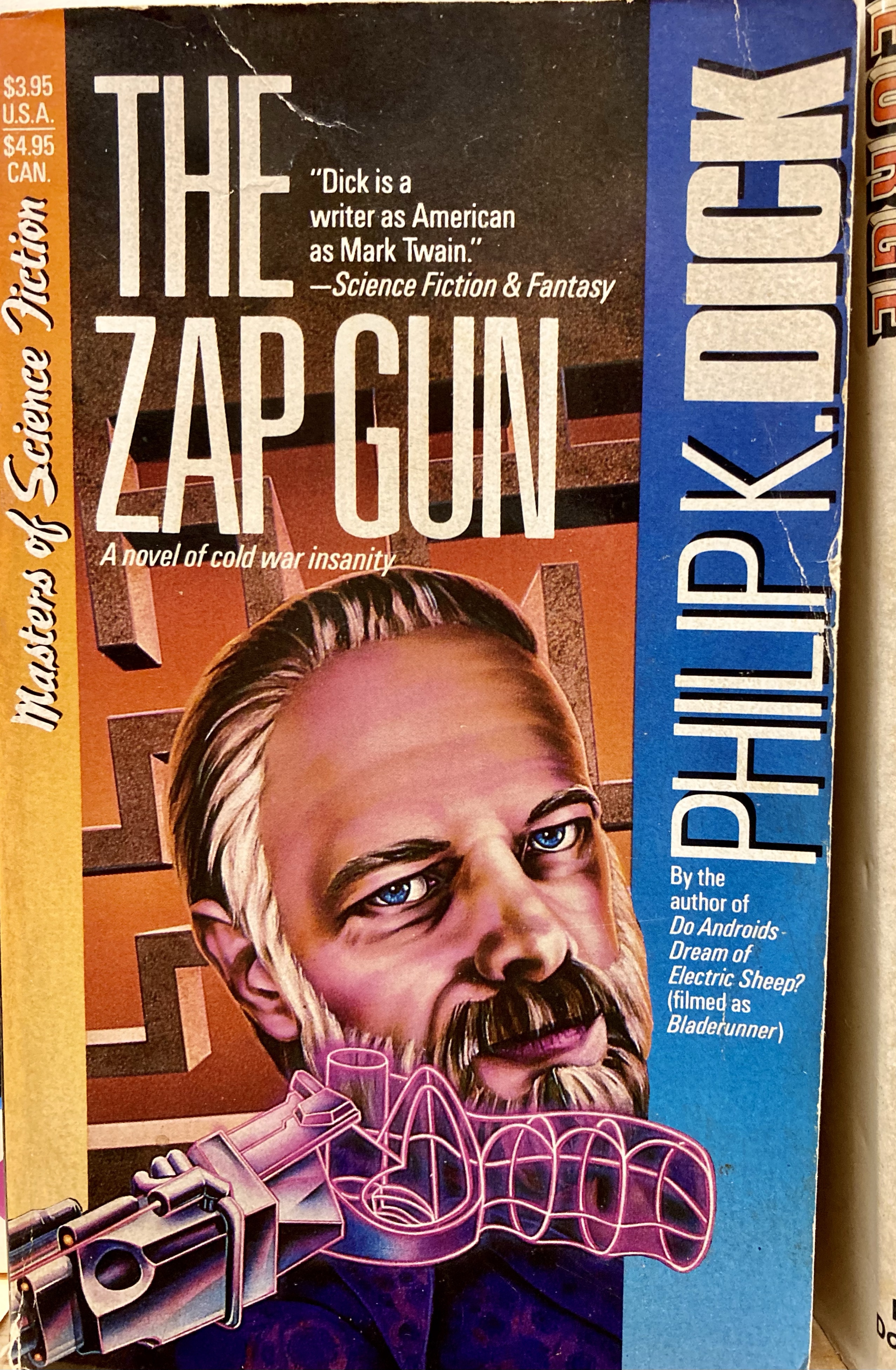

In the meantime, I picked up some of the books that Thomas Pynchon had blurbed, often preferring his blurbs to the novels he blurbed.

I read some of his juvenalia again, like “Ye Legend of Sir Stupid and the Purple Knight”:

In May I finally read Pynchon’s latest (last?!) novel Bleeding Edge.

I looked online for bootleg editions of the material that showed up in Slow Learner. I read more of Slow Learner, leaving two tales…just to leave them, just to not have exhausted a…final supply?

In the absence of March Madness college basketball, I ran a silly bracket of dystopian/sci fi writers — “zeitgeisty” writers” — and Pynchon won, beating out J.G. Ballard, who I still think should have won.

(Someone wrote in to tell me that it was the “most shite” thing that I’ve ever done on the blog and to never do it again. Thanks guy! That felt good.)

And also,

I worried, fretted, washed, ranted, cried even at times, but

I never missed a meal and my family had a regular four square game going and Florida actually gave us real Spring weather, crisp and cool and sunny, and the trees bloomed and budded, and I figure in some ways I was as happy as I’ve ever been.

And the year passed, with its plague, its violent racism, its protests, all swelling into its ugly electioneering.

And then this Spring 2021 semester I went back in, setting my feet on campus for Tues and Thurs classes and the world seemed a bit more normal. We got a normal, boring president; a lot of us started to get the vaccine. Things felt…better? Like other folks, I looked forward to hanging out with all the folks I’d seen so little of in the last year.

I got my first vax jab a few weeks ago; I get my second this Friday. I look forward to hanging with “The Boys” (and “the girls,” and etc.)

At some point in the last year I shelved Thomas Pynchon: A Bibliography with the rest of the Pynchon books in the house. I just assumed that it was mine, that it was an artifact of the plague year. My covid acquired.

But last week my librarian let me know, Hey, USF wants that Pynchon book back. I held on to it a second week, revisiting it in parts, but mostly to write this here blog post, mostly to find another way to say, Hey, what a year, eh? I’ll drop it off with my librarian tomorrow, but I think it’ll make me feel a bit sad.

But also maybe relieved.

A new edition of Ann Quin’s third novel Passages is out in a few days from indie juggernaut

A new edition of Ann Quin’s third novel Passages is out in a few days from indie juggernaut

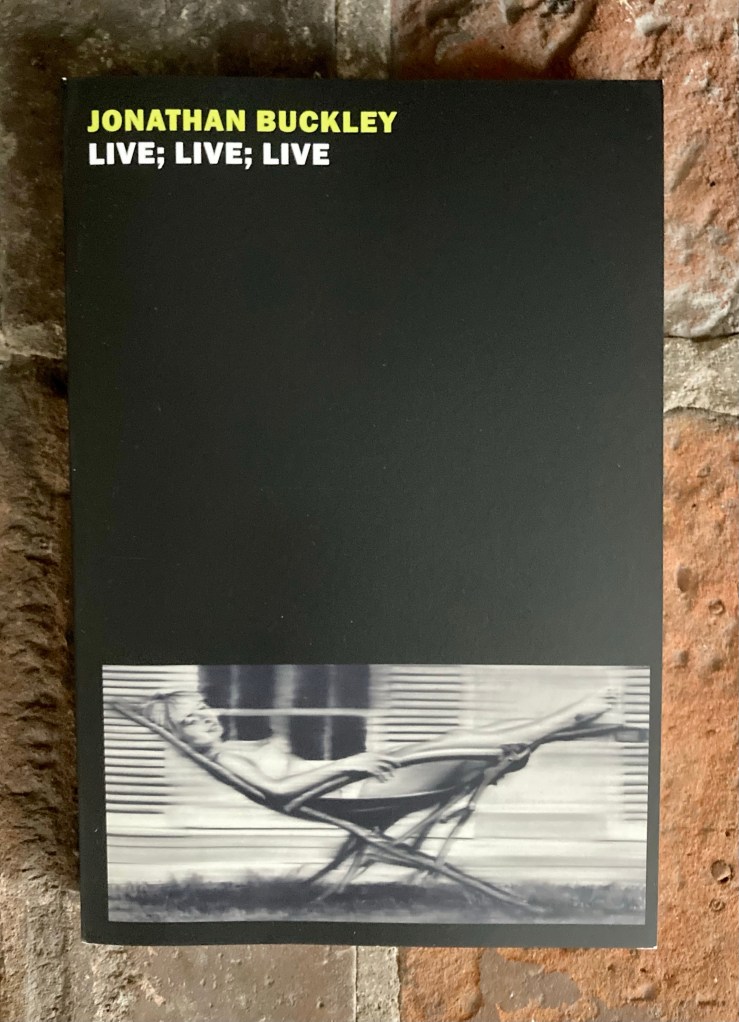

Jonathan Buckley’s novel Live; live; live is forthcoming from NYRB in a few weeks. Their blurb:

Jonathan Buckley’s novel Live; live; live is forthcoming from NYRB in a few weeks. Their blurb: