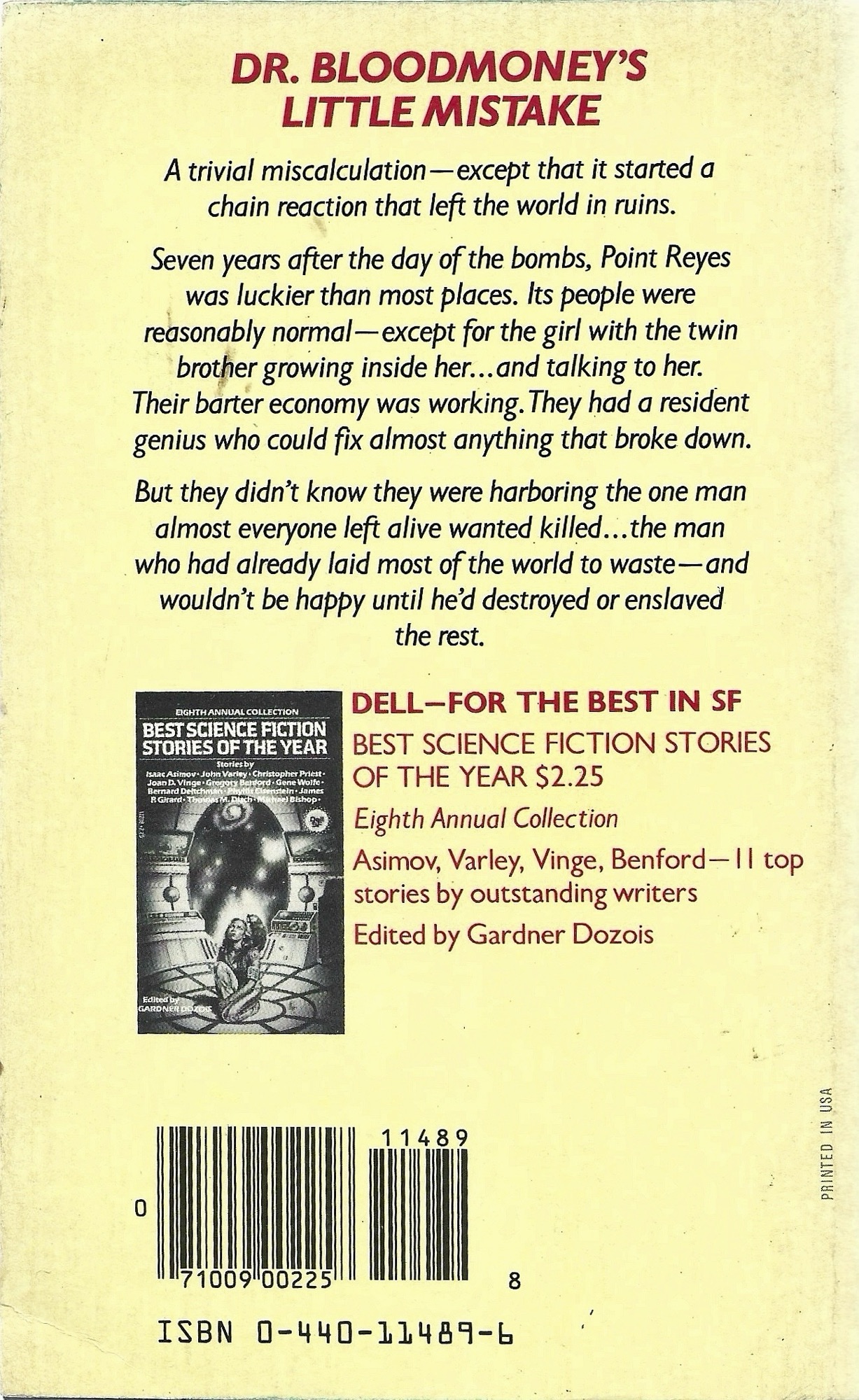

Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Notes on Chapters 15-18 | Ghostly crawl.

Notes on Chapters 21-23 | Phantom gearbox.

Chapter 27 focuses on Hop Wingdale. Out on tour with his band (and maybe on the run, sorta, from Daphne) he meets up with his agent Nigel Trevelyan in Geneva. Hop refuses to play “any of these Nazi joints popping up all over,” but sympathetic Nigel has something kosher for the clarinetist: the “Trans-Trianon 2000 Tour of Hungary Unredeemed,” an anarchic, carnvialesque motorcycle race that will culminate in Fiume (aka Rijeka — a bilocated multilingual, multiethnic city-state). Everyone in Shadow Ticket is headed to Fiume — you too, reader.

Halfway through this short chapter, things take a spooky twist: Nigel dispenses with the tour stuff to move to “the real business at hand…Hop’s ‘booking agent’ turns out to be a” secret agent. He’s so secret that he literally physically morphs “through a smooth frame-by-frame personal transition, gaining a couple inches in height, mustache narrowing to little more than a lip gesture, discreetly tinted indoor specs.” It turns out that “the real business at hand” is the worsening “antisemitism situation.” Hop’s on a mission; the tour is a cover for him to scout “possible escape routes from Central Europe should a sudden exodus become necessary.” Nigel suggests that the “key connection will be to Fiume, also known as Rijeka.” He warns Hop that: “We’re in for some dark ages, kid.”

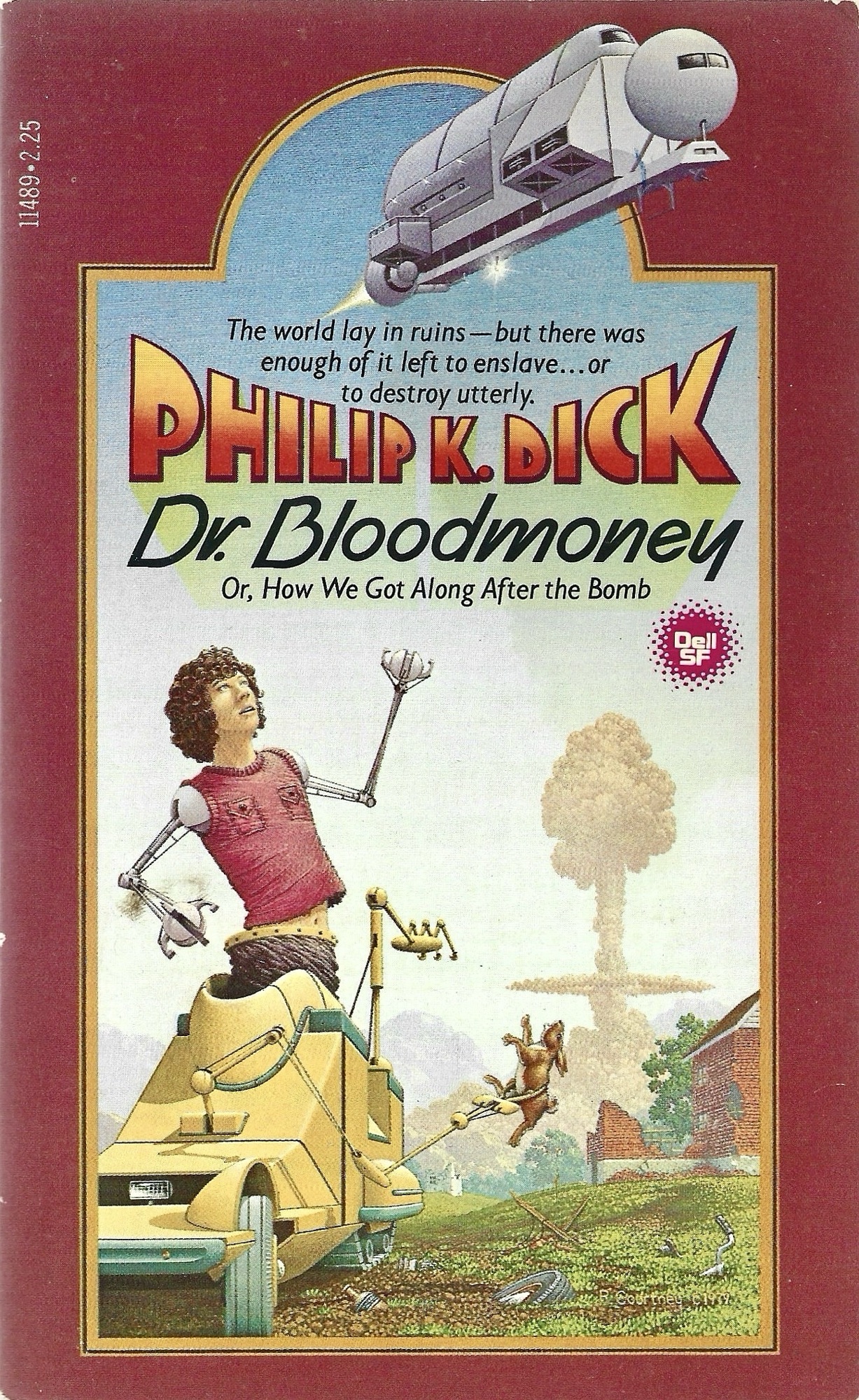

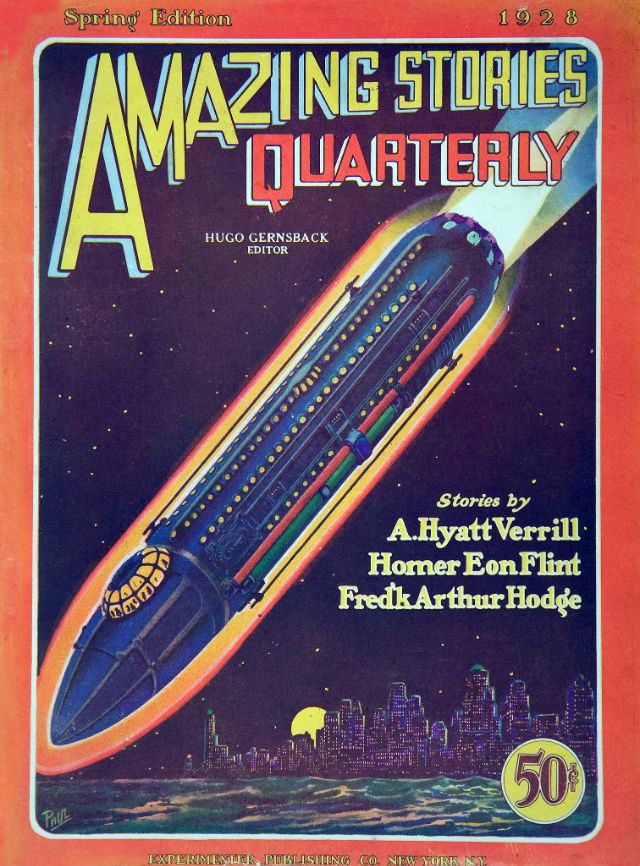

Nigel has arranged luxury transport for his asset: a “road-Pullman all lit up, size of a railway sleeping car, futuristic as something just rolled off the cover of Amazing Stories.” The notation of a “road-Pullman” threw me at first — Pynchon has evoked something like a sci-fi bus, sure, but I had always identified the term “Pullman” with railroad cars — like the one Hicks journeyed eastward out of Illinois (while chatting with a phantom Pullman porter) back in Ch. 17. Perhaps it’s just slang here?

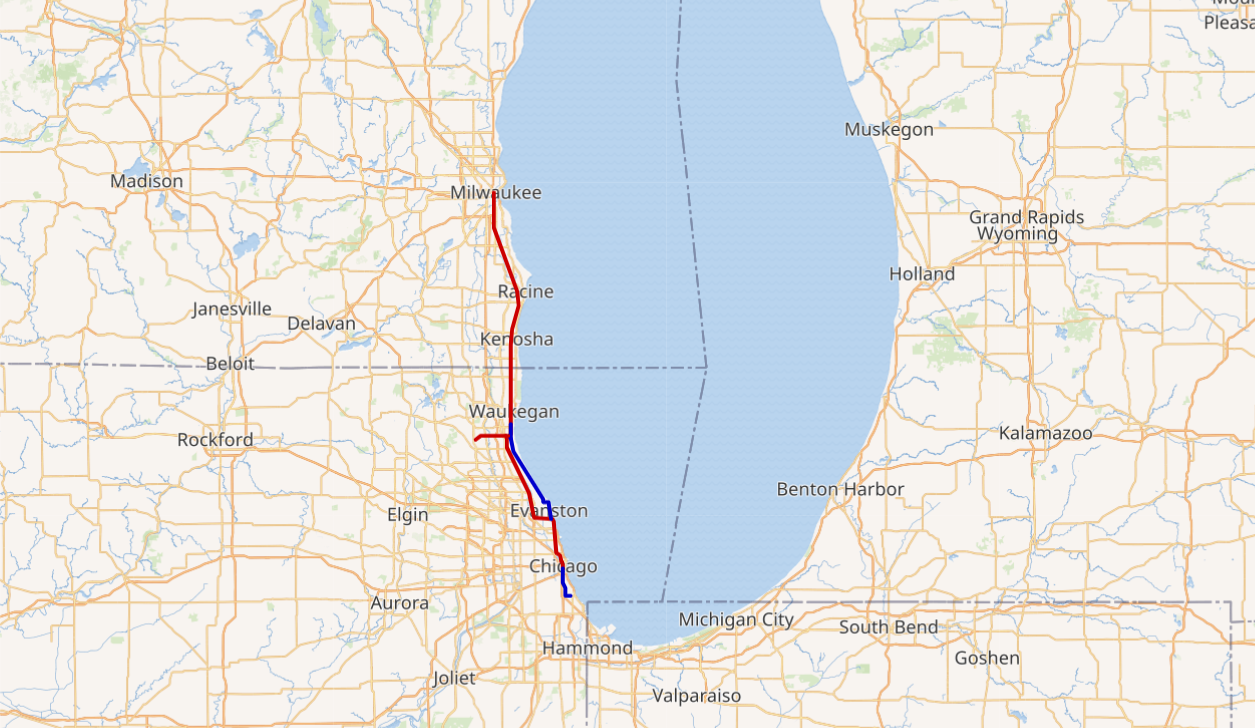

Chapter 28 begins with homesickness blooming into idealized nostalgia: “Sometimes all Hicks wants is to be back in Milwaukee, restored to normal life, to a country not yet gone Fascist, a place of clarity and safety, still snoozy and safe…” I feel that Hicks!

The chapter then moves through a series of short vignettes that move the plot forward (however obscurely). Terike will be taking off on the Trans-Trianon bike tour; Hicks is worried that Harley-riding Ace Lomax will be there too. Hicks checks in with Egon Praediger, who implicitly offers to pay Hicks to kill Bruno Airhart. Hicks declines, claiming that assassination “draws too much kiddie outlaw attention” — but we get the sense that he’d like to find more meaningful work than just one “high-risk orangutan job after another, always in the service of someone else’s greed or fear.” Hicks also visits journalist Slide Gearheart, who questions whether or not the former strikebreaker might find forgiveness or “redemption via Cheez Princess.” Cynical Slide is dubious, but their exchange recalls psychic Zoltán von Kiss’s riff in Ch. 22 on the redemption of lamps: “even the most hopelessly ill-imagined lamp deserves to belong somewhere, to have been awaited, to enact some return, to stand watch on some table, in some corner, as a place-keeper, a marker, a promise of redemption.”

Chapter 28 then gives over to Daphne, who will finally, “in a turbulence and drift of multiple unlikelihoods” meet up with her estranged father Bruno. She meets him in Night of the World, a multi-floor cabaret whose “circles of depravity…go corkscrewing down…toward ancient depths few have been willing to dare, each with its own bar and dance band and clientele.” The image of the bar and its name recall German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s notion of “die Nacht der Welt” a reference to human subjectivity as a chaotic, unconscious darkness that lies beneath rational thought. Pynchon has previously referenced Carl Jung in Shadow Ticket, and while I don’t really think of Jung as a follower of Hegel, his concept of “the shadow” seems to resonate with Hegel’s “Nacht der Welt.”

Pynchon’s description of the Night of the World is worth sharing at length: “Each table here has a small circular cathode-ray tube or television screen set flush in the tabletop, throbbing more than flickering with shaggy images of about 100 lines’ resolution…Numbered push-button switches allow you to connect to any other table in the place and watch each other as you chat.” As if to underline the parody here of our twenties’ contemporary screen culture obsession, a strange man — it’s Bruno, spoiler — tells Daphne the screens are, “The future of flirtation…here they call it Gesichtsröhre, or ‘Face-Tube.’ ”

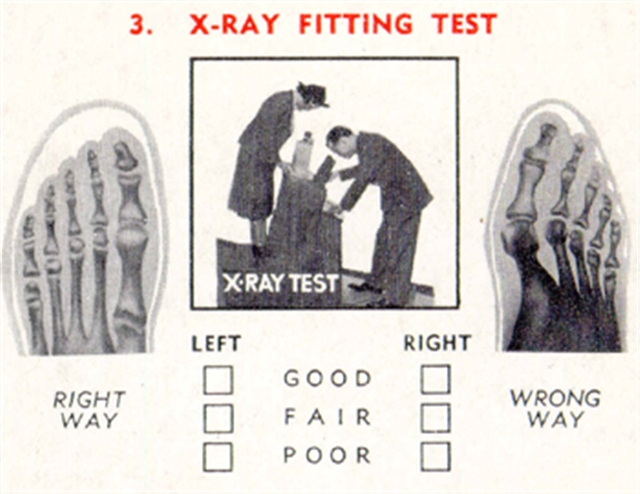

But the theme here goes beyond the parodic surface. Looking in the screen, “Viewers sometimes do not agree on the nature of the image. Pareidolia is common. You look down into it, like a crystal gazer, and faces loom unbidden.” The language here recalls Hicks gazing into the shoe-fitting fluoroscope back in Ch. 15 and seeing “a face he’s supposed to know but doesn’t, or at least can’t name.” Is this image the shadow — like, the Jungian shadow? The night of the world? Or just Hicks’s paranoid pareidolia cooking up an answer to a corkscrew of images that amount to chaos.

Anyway–the weird stranger is Papa Bruno. Soon there’s another of Pynchon’s original songs and a daddy-daughter dance. Bruno looks much, much younger, and creepily, more virile. How? “These days the Central European backwoods, Bruno explains, are full of ‘scientists,’ elsewhere known as witch doctors, working miracle effects in chemical defiance of time.” All in the service of horny plutocrats, natch.

Daddy and daughter agree on a movie date and go to see “Bigger Than Yer Stummick (1931), the latest hit starring child sensation Squeezita Thickly, which is about, well, eating, actually.” The description of Bigger Than Yer Stummick is, for me, a highlight of Shadow Ticket. It’s well-over whatever line of “good taste” some folks might set down (Squeezita Thickly!), over-indulgent, and I love it. Here’s Pynchon the auteur framing a special effects shot:

“A pot of soup, approached from overhead, now smoothly lap-dissolving into a giant swimming pool full of bathing beauties, bordered by palm trees and food pitches, offering an array of snacks from roast turkey drumsticks to deluxe hot dogs smothered in sport peppers and dripping green-blue pickle relish strangely aglow, even though the movie’s supposed to be in black-and-white, and gigantic Italian sandwiches quite a few feet long, and glutton-size ice-cream extravaganzas and oh well that sort of menu…”

I think I’ve pointed out in every single one of these riffs some instance of glow-in-the-dark material, like the “green-blue pickle relish” that manages supernatural radiation here.

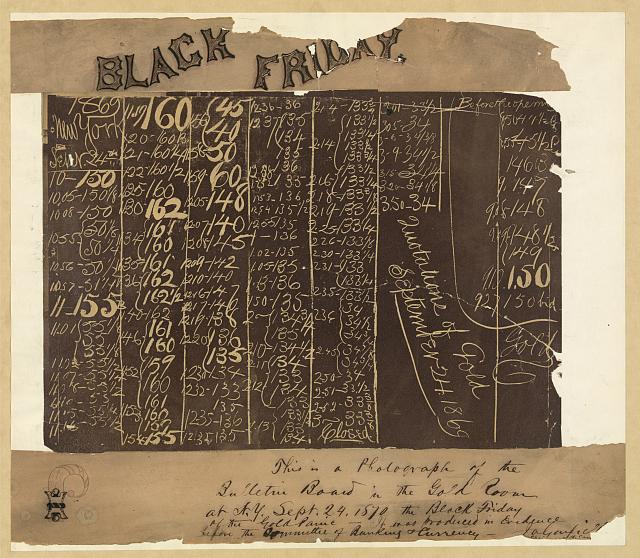

The Bigger Than Yer Stummick routine isn’t just goofy fun though. It showcases the zany-sinister paradox that Pynchon is so good at evoking. The film is about eating, and thus, highlights hunger via hunger’s absence. And the film’s audience is hungry: “Back in the States, every showing of this movie, no matter where, has collapsed well before the second reel into civic disorder—screens across the nation presently inscribed with knife scars, fork tracks, spoon indentations as audiences, many of whom haven’t seen a square meal since the start of the Depression.” As the film progresses, it gets darker; first “the music has shifted grimly minor,” and soon folks are “shooting at each other, both semi- and fully-automatically, not always in play, plus setting off spherical anarchist-style bombs.” There’s a war on the horizon — “We’re in for some dark ages, kid” — a war that will cannibalize the world. Consider Egon Praediger’s cocaine-inspired reverie back in Ch. 21. He predicts the coming war; although it will entail “a violent collapse of civil order” it will also point to a “horizon with enough edible prey to solve the Meat Question forever…”

One last note on Bigger Than Yer Stummick — the title is a take on the idiom “your eyes are bigger than your stomach,” meaning that you’ve overestimated your hunger or taken on more than you can handle. The missing word is “eyes” and two of the words are in alternate spellings. Perhaps Pynchon is inviting us to see not just a missing “eye” but a missing “I.” Maybe there’s something here with the shadow self, the missing or submerged self, the moral self that would love to transcend the material plain, the stomach of reality — if you weren’t so fucking hungry all the time.

Post-film credits, things get weird between Daphne and pops. The narrator tells us that, “If Daphne has been hoping for something incestuous yet romantic, she’s once again reminded how very little anybody can put past Bruno.” Uh, okay. Bruno wants to euchre her of her cattle/cheese rights; he needs cash as “Some very bad people are after your old Pop, itchin to take down the Al Capone of Cheese. Forces I once had no idea even existed.” We then switch back to Hicks and Slide, with Slide apparently hep to an apparent incest grift on Daphne’s point: “Word around is she’s been working her own counter-scheme, luring Bruno deeper into a sordid and forbidden sex affair while hired photo crews secretly record every last shameful detail—” Hicks is shocked. But, like — incest, power, plutocracy. Daphne skips town, possibly hunting Hop.

Ch. 28 snowballs, adding characters, like “Heino Zäpfchen, a much sought-after Judenjäger, or Jew-tracker”; the Vladboys, an anti-semitic gang of hooligans “desperate for Nazi approval” who are engaged in streetfighting; and “Zdeněk, who claims to be an authentic Czechoslovakian golem.” Thomas Pynchon is 88 years old. I have no idea how long he’s had this novel percolating, and I’m so thankful to get to read at least one more, and I think it’s a really good novel, but, yeah, there’s a sketchiness to it — a sense that the old master might not have the energy or time to flesh out all of the big ideas. Or, alternately–Shadow Ticket is leaner and meaner than the epics it points towards (Against the Day and Gravity’s Rainbow).

Okay, so I just mentioned Against the Day and Gravity’s Rainbow — parenthetically, sure. But “Zdeněk, who claims to be an authentic Czechoslovakian golem,” provides a clear link to Mason & Dixon. Golems show up in Mason & Dixon, first appearing in Chapter 49, where the narrator refers to “Kitchen-size” ones, not the giants we expect. Cf. Zdeněk being described as a “sort of snub-nose golem.” Then, in chapter 50, there’s an extended riff on the Rabbi of Prague (I wrote about it here). Back in Shadow Ticket, Zdeněk “explains, ever since Judah Loew was Rabbi of Prague, a body of powerful golem lore has been passed down, rabbi to rabbi.”

The (long) chapter ends with a flurry of references: to Imi Lichtenfeld (Hungarian-born inventor of the Israeli martial art krav maga (“’You could think of it as Jew-jitsu,’ sez Zdeněk”); to “a glamorous, indeed sultry, robotka or female robot named Dushka“; and to “some business in Transylvania we needed to take care of.”

Chapter 29 is an ultracompressed precis of Central European history in the 1920s, the point of which is the origin of the Trans-Trianon motorcycle ride (that’s not really the point):

“Sometime in the period 1920–25 the first tentative motorcyclists set out on low-horsepower machinery, army dispatch bikes, city-street models. While the ’20s roared in Chicago and American expats whooped it up in Paree, while Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman went gliding through the city traffic of Petersburg filming a newly tsarless and not yet Stalinized people” —

— “while Berlin still offered unparalleled freedom and refuge to heretics and asylum seekers of all persuasions, this is what was going on in the strange ring of historical debris that had once belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary—bikers in motion, some riding clockwise, some counter-, not a rally, not a race, not a pilgrimage, no timekeepers, no grand prizes, no order of finish, no finish line for that matter, though some, speaking metaphysically, say if there were one it’d be at Fiume. Rijeka, whichever.”

Bilocation, anarchy, telekinesis.

Watch Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Vertov; dir. of photog. Kaufman).