“The Anarchist: His Dog”

by Susan Glaspell

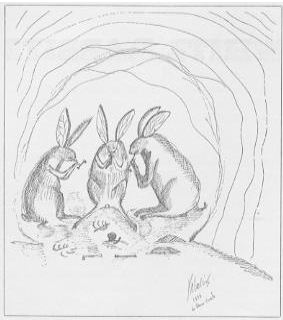

Stubby had a route, and that was how he happened to get a dog. For the benefit of those who have never carried papers it should be thrown in that having a route means getting up just when there is really some fun in sleeping, lining up at the Leader office—maybe having a scrap with the fellow who says you took his place in the line—getting your papers all damp from the press and starting for the outskirts of the city. Then you double up the paper in the way that will cause all possible difficulty in undoubling and hurl it with what force you have against the front door. It is good to have a route, for you at least earn your salt, so your father can’t say that any more. If he does, you know it isn’t so.

When you have a route, you whistle. All the fellows whistle. They may not feel like it, but it is the custom—as could be sworn to by many sleepy citizens. And as time goes on you succeed in acquiring the easy manner of a brigand.

Stubby was little and everything about him seemed sawed off just a second too soon,—his nose, his fingers, and most of all, his hair. His head was a faithful replica of a chestnut burr. His hair did not lie down and take things easy. It stood up—and out!—gentle ladies couldn’t possibly have let their hands sink into it—as we are told they do—for the hands just wouldn’t sink. They’d have to float.

And alas, gentle ladies didn’t particularly want their hands to sink into it. There was not that about Stubby’s short person to cause the hands of gentle ladies to move instinctively to his head. Stubby bristled. That is, he appeared to bristle. Inwardly, Stubby yearned, though he would have swung into his very best brigand manner on the spot were you to suggest so offensive a thing. Just to look at Stubby you’d never in a thousand years guess what a funny feeling he had sometimes when he got to the top of the hill where his route began and could see a long way down the river and the town curled in on the other side. Sometimes when the morning sun was shining through a mist—making things awful queer—some of the mist got into Stubby’s squinty little eyes. After the mist behaved that way he always whistled so rakishly and threw his papers with such abandonment that people turned over in their beds and muttered things about having that little heathen of a paper boy shot. Continue reading ““The Anarchist: His Dog” — Susan Glaspell”