He was born in New York City on August 1, 1819, the third of eight children.

His mother added a final e to the family name after her husband’s death, perhaps to distance herself from his financial problems.

His grandfathers had participated in the Revolutionary War.

At the time of his birth, his father was a fairly prosperous importer of luxury items such as silks and colognes, and his family lived well in a series of houses around New York City, each with comfortable furnishings, refined food and drink, and household servants to keep things in order.

Such lineage and lifestyle notwithstanding, family letters suggest that he was a rather unremarkable child, at least in his father’s eyes.

In 1826, when he was seven years old, his father wrote of him to his brother-in-law : “He is very backward in speech & somewhat slow in comprehension, but you will find him as far as he understands men & things both solid and profound, & of a docile & amiable disposition.”

Instead, the family’s highest praise often went to his older brother

In 1830, after years of increasing debts, his father’s business collapsed, and the family moved—or, some might say, fled—to Albany, New York, to seek sanctuary among his mother’s relatives.

His father died of pneumonia in 1832, entirely bankrupt and raving deliriously from fever.

After his father’s death, he, at 13 years old assumed the responsibilities of a “man” in the family.

With his father’s death and the family’s debt, he was now obliged to seek employment.

He worked as an errand boy at a local bank. A clerk at his brother’s store. A hand on his uncle’s farm.

After, he enrolled in Albany Classical School in 1835 in order to prepare for a business career, but once there, the young man whom his father had described as inarticulate and “slow” discovered that he had an interest in writing.

He required the requisite knowledge of Latin to obtain a teaching position in the Sikes district of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in the fall of 1837.

He found teaching in a country school unappealing at best.

His students were, by his own accounts, dull and backward

An early biographer hints at “a rebellion in which some of the bigger boys undertook to ‘lick’ him.”

He left the teaching position after one term, and in 1838 he enrolled in the Lansingburgh Academy, where he was certified as a surveyor and engineer but failed to find the employment he had hoped for as part of the Erie Canal project.

In 1837 he took his first trip to sea.

Several of his uncles were sailors, and he had grown up hearing about their exploits.

He sailed out as a cabin boy on the merchant ship St. Lawrence on June 4, 1839.

He spent four months aboard, including a visit to Liverpool that would provide inspiration and material for scenes of England’s urban poverty in one of his early novels.

None of his letters from this voyage have survived.

When he returned he found his mother and sisters in serious financial trouble, and desperate for extra income, he once again took a teaching job, only to lose it a few months later. He visited an uncle in Galena, Illinois, hoping to find better job prospects there, but failed.

He returned to New York and signed on with the New Bedford whaler Acushnet.

On January 3, 1841, he shipped for the Pacific.

He had signed up for the customary four-year tour aboard the whaler.

Once in the fleet, he quickly grew restless under the conditions imposed by his captain.

Rations were scanty, work and discipline were harsh, and, perhaps most unforgivably, time at sea was continually extended in search of greater hauls.

The Acushnet made one of its few stops in the port of Nuku Hivain the Marquesas in June 1842.

He jumped ship on July 9, 1842.

By the time the Acushnet completed its voyage, fully half the crew had deserted, and several more had died.

He fled into the island’s interior, where he was taken in by the Taipi.

Known as fierce warriors who were actively hostile to neighboring groups, the Taipi were also reputed to practice cannibalism on their conquered enemies.

He lived among the Taipi for four weeks before finding his way back to Nukuheva, where on August 9 he went aboard an Australian whaler named the Lucy-Ann.

Life aboard the Lucy-Ann proved to be even harder than it had been on the Acushnet. The captain of the ship had fallen ill and was taken ashore at Papeete, Tahiti’s largest port, to be treated, and while the ship was anchored, the crew revolted.

Along with most of the crew, he was arrested as a mutineer and handed over to the British authorities, who locked him up in a makeshift outdoor jail.

Conditions at the “calabooza,” as the jail was called, were far better than they had been aboard ship.

Though the inmates did sleep with their feet locked in wooden stocks, they were well fed and were allowed a great deal of leisure and liberty during the day—including being allowed small day-trips across the island. This laxity resulted in the escape of four prisoners. He and his friend were among these escapees.

After touring the Society Islands briefly, they signed up on yet another whaler, the Charles & Henry.

He left that ship on May 2, 1843, in Lahaina, on the island of Maui, Hawaii. He traveled to Honolulu, where he went to work at several odd jobs, including as a clerk in a shop and a pin-setter in a bowling alley.

On August 17 he joined the crew of the USS United States as an ordinary seaman.

He observed flogging routinely used as punishment per existing naval codes of discipline, and he also saw several burials at sea. The United States docked in Boston 14 months later.

Upon his return to Lansingburgh, his tales of the South Pacific made him a minor celebrity.

Friends and family encouraged him to write about his experiences, and he did, transforming his time among the “cannibals” of the Marquesas into a novel published to critical acclaim and financial reward in 1846.

Around this time, he began courting a family friend who lived in Boston, the daughter of the powerful chief justice of the Massachusetts supreme court.

Buoyed by his recent literary success, he married her on August 4, 1847.

Letters suggest a happy, flirtatious union, at least early in the marriage.

They would eventually have four children together.

He made an unsuccessful attempt to gain a government position in Washington, D.C. and had to rely on the support of his father-in-law to supplement his income.

He then wrote two financially-successful novels, which he would later refer to as “two jobs—which I did for money—being forced to it, as other men are to sawing wood. … [M]y only desire for their ‘success’ (as it is called) springs from my pocket, & not from my heart.”

While vacationing in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in the summer of 1850, he met a successful New England writer, and struck up an immediate and intense, though short-lived, friendship.

The two writers spent a great deal of time together discussing all manner of intellectual and philosophical matters.

In September 1850, he borrowed money from his father-in-law and bought a farm in Pittsfield, a mere six miles from his writer friend.

In 1851, he dedicated his next novel to his friend.

The novel was not a success.

His next novel was even less successful.

An 1853 fire at his publishers warehouse destroyed most of the existing copies of his novels.

He tried unsuccessfully to obtain a consular appointment.

He completed and unsuccessfully attempted to publish two other novels in the 1850s.

One of these was a story about tortoise hunting.

Both manuscripts are lost.

His physical and mental health continued to concern his family.

He suffered severe back problems and recurrent eyestrain; family letters also hint carefully at “ugly attacks” of a more psychological nature.

In 1856, his father-in-law financed a seven-month trip during which he visited Europe and the Holy Land.

On the trip out, he stopped in Liverpool and spent three days with his successful New England writer friend, who was serving there on a diplomatic appointment. The friend noted in his journal that he appeared “much as he used to (a little paler, and perhaps a little sadder).”

His next novel, the last published in his lifetime, met with critical and popular rejection.

He failed to earn money on the lecture circuit.

Once again he tried to obtain a consular appointment, but failed.

He continued to meet rejection in his attempts to earn a government position, and his first volume of poetry was rejected for publication in 1860.

He sold his country estate to his brother and bought his brother’s house in New York City.

They visited their cousin on the Virginia battlefields in 1864, leading to a series of poems published in 1866.

He finally won a position as a customs inspector in New York in 1866—which marked the end of his attempts to sustain a living through writing.

He would work there for nineteen years.

Many of his friends died in the 1860s.

His eldest son died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1867. He had argued with his son the night before.

His wife consulted her minister about the possibility of legally separating from him.

He may have also developed alcohol-related emotional problems over time.

She stayed with him until his death.

After his 1889 retirement, he resumed writing as his primary occupation.

Much of his late work was poetry.

He died of heart failure at home in his bed on September 28, 1891, having been largely forgotten by the literary world in the thirty years since his last novel was published.

The New York Times misspelled his name in its obituary.

Virtually all of the letters he wrote were destroyed after his death, as were many of his manuscripts and writing notes.

In his

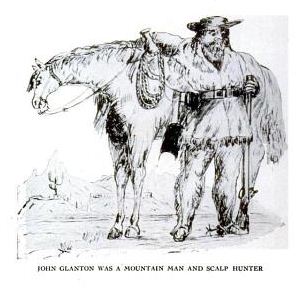

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

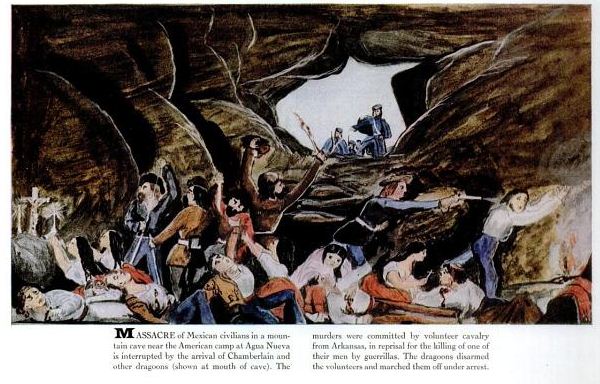

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

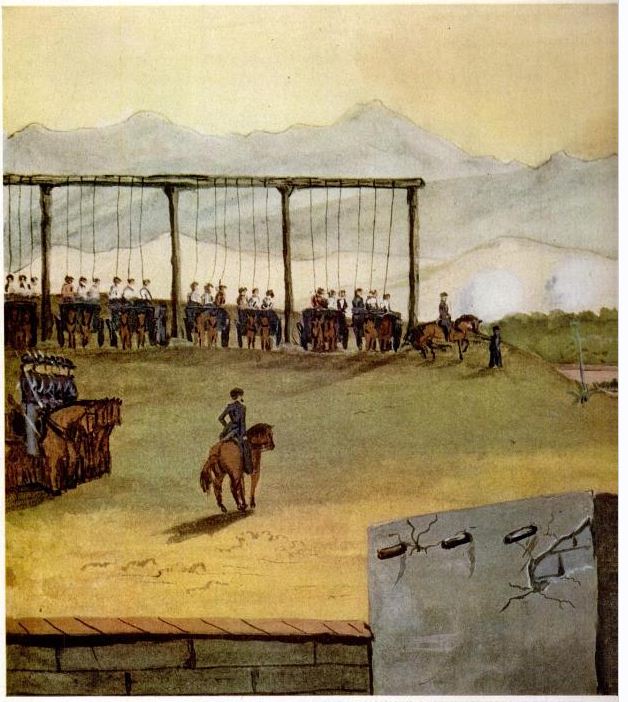

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s