Like a lot of US Americans I didn’t sleep too well last night. I went to bed too late and I rustled myself into some form of consciousness way too early. A veteran of past election eves, I did not overimbibe, but still felt groggy enough and well just plain like well disconcerted discombobulated discouraged enough to cancel meetings with my classes for the day. I didn’t have anything to give.

While I was in no way shocked by the results of the 2024 elections, I am nevertheless big-w Worried about all the things that may unfold, quickly, and without organized opposition, in the next six months. As has been the case for most of the presidential elections I’ve voted in, I voted against a candidate instead of for a candidate. I knew in Florida that my vote probably wouldn’t matter too much anyway.

I made myself go outside of my house into “Florida,” into Northeast Florida, which is, of course, also inside of my house, Florida, but I went outside early to take the air and look around. It was also garbage day in the neighborhood. I had a can with some nasty double-bagged rotten Jack O’Lanterns. We carved them on Halloween night and they wilted to a gray and black fuzz swarmed over with pestilence. I had to scrape their guts into the garden bed and hose the whole mess down. It’s not supposed to be this hot here this time of year, only it is and it has been, like regularly, consistently, predictably for well over a decade. The Florida air I stepped out into was gross: sticky, muggy, humidity near ninety percent and maybe 82° at nine in the morning. It did not feel like summer nor fall, but some other gross fifth season. None of this was colored by mood.

My mood was and is grim. I knew that voting for the incumbent’s proxy was simply kicking a can down the road; I knew that I was endorsing a system I had no belief in and that no one else I knew really seemed to believe in. I think I wanted just a little bit of the latter half of the 20th century to trickle down to my children, who are no longer really children. But it felt like a gross summer’s eve on this fall morning, and I remembered that climate change, which is to say global warming, which is to say the warming of the earth’s habitable surface as the result of fossil fuels—this so-called “climate change” didn’t even seem to be a blip in this election cycle. Again: kicking the can down the road, whistling past the graveyard, etc. Ostriches don’t really bury their heads in the sand though, and we all gotta know that the bill for the twentieth century is way past overdue.

But ostensibly this is a blog about literature or art; I don’t think anyone comes here for me to rant. So what am I reading?

I have been reading two books (three, really, or maybe more) and auditing two books. Audiobooks first: I am about half way through Dan Simmons’ Fall of Hyperion and I want to quit. I liked Hyperion but this one is just…I don’t have anything to say about it, except that I am sympathetic to Simmons’ anti-imperialist critique and I’m generally simpatico with his appropriation of the Romantics into a sci-fi epic (although, like, where the fuck is Blake?)—but the first book Hyperion was much better. Maybe it’s because he had a form to steal (Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales). I listen to this book in waking hours: driving, cooking, chores, etc.

The other audiobook is a fantastic rendition of John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. I do not listen to this book during waking hours; I fall asleep to it (or to Reich’s Music for Eighteen Musicians or to Sleep’s Holy Mountain or something else). Specifically, I’ve been falling asleep somewhere between chapters seven and eight this week. I love this book so much. I love the film version that came out like ten plus years ago, with Gary Oldman as Smiley. I used to love falling asleep to that film. I don’t actually know what happens in the narrative.

The two books I switch between before falling asleep to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy:

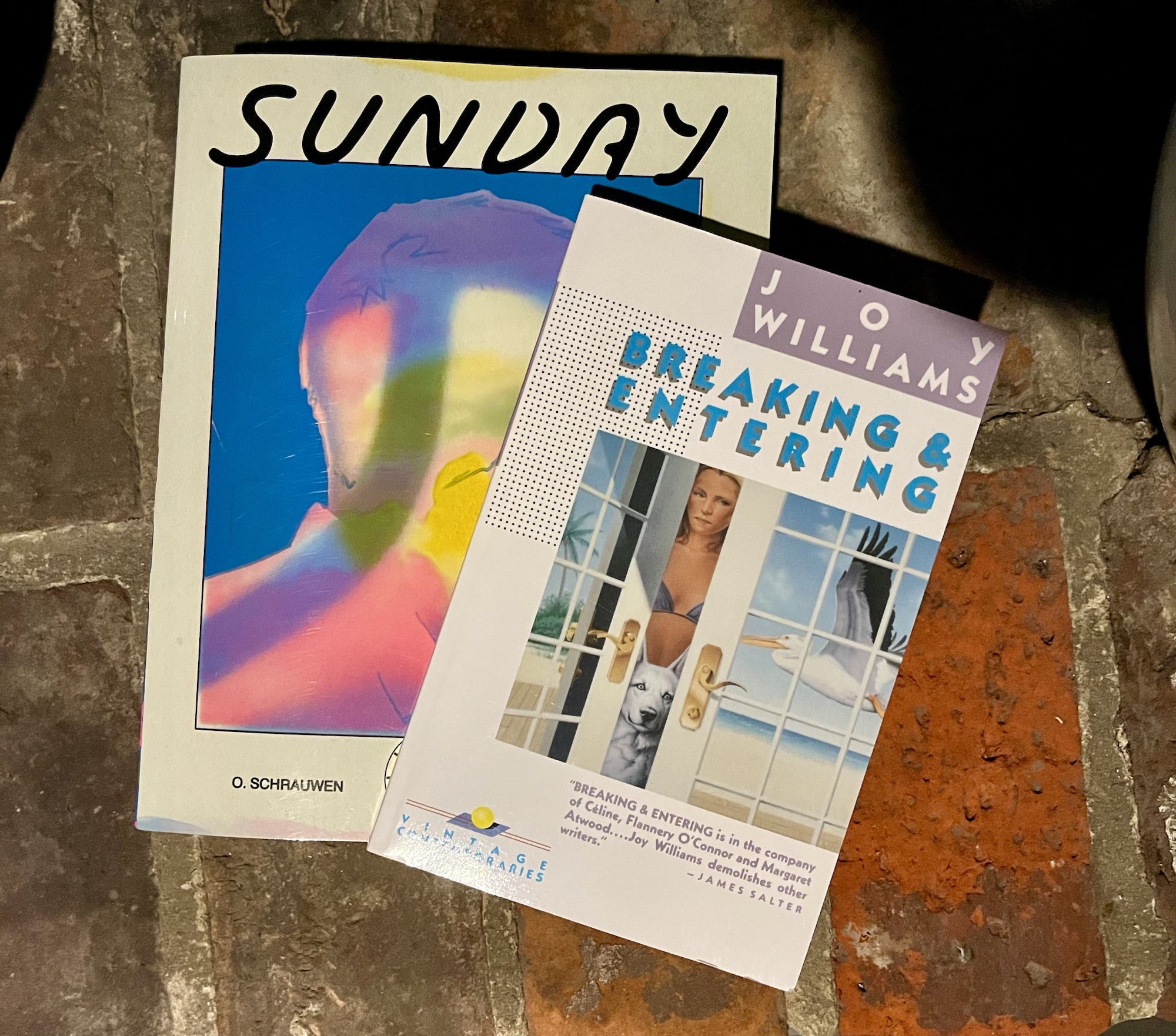

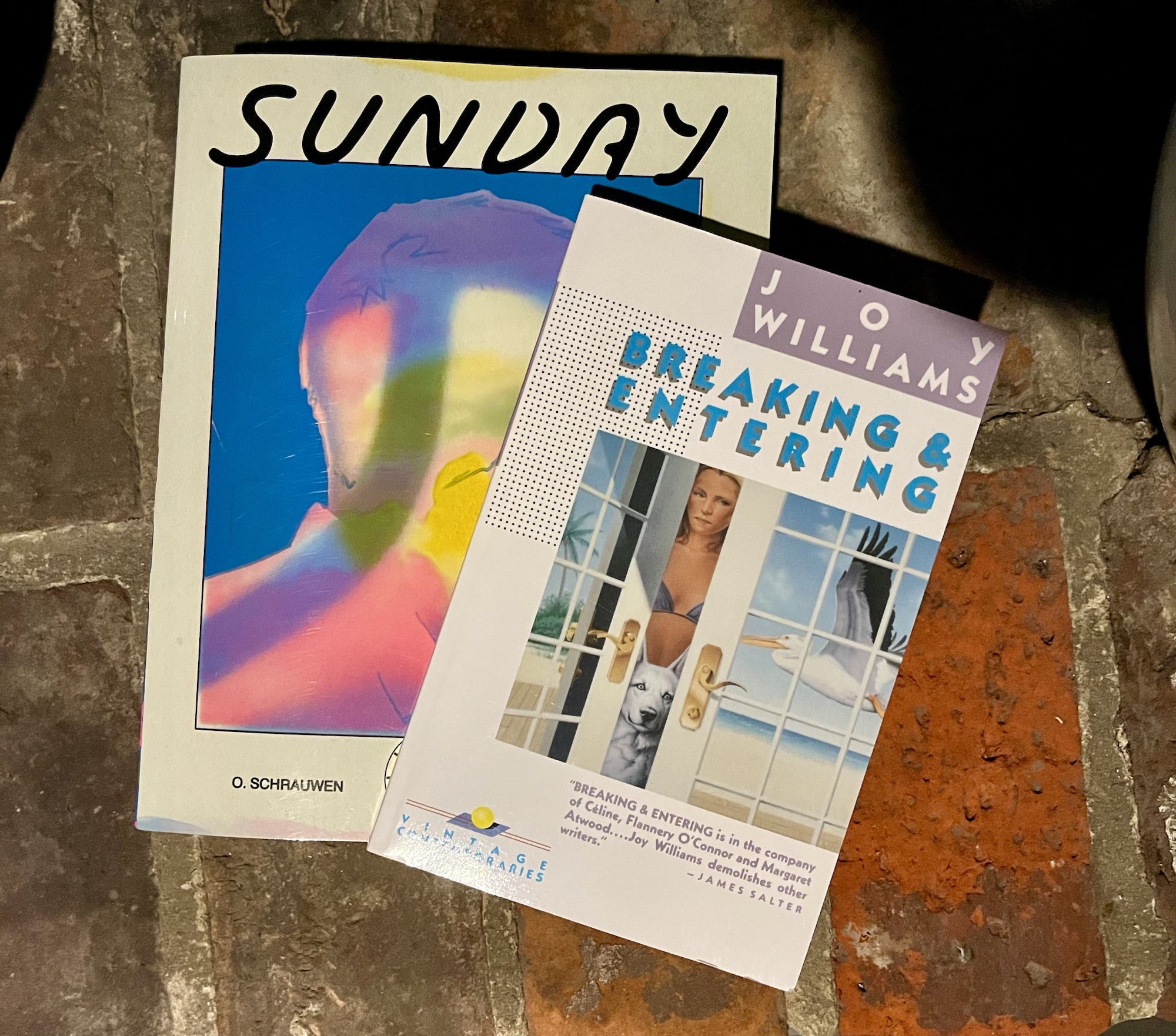

Olivier Schrauwen’s Sunday and Joy Williams’ Breaking and Entering.

Sunday is a true graphic novel: that term, “graphic novel,” a marketing gambit I’m sure, gets appended to pretty much any cartoonists’ self-contained work of, say, fifty-plus pages. But a lot of what we (and we includes very much me) call graphic novels are really short stories in comix/cartooning form. Schrauwen’s effort is a real novel, a real graphic novel a la allah ah lah lah From Hell or Jimmy Corrigan. It’s really fucking great, and if this weren’t a low-effort I am writing this for me and not you post, I would tell you why I think it’s really fucking great (I would describe the story, the so-called story, such as it is; I would riff on all the motifs; I would get lost in the coloring. I would I would I would…)

The other book I’ve been reading, the one I read after I read a chapter of Sunday and before I fall asleep to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is Joy Williams’ 1988 novel Breaking and Entering, which is about a strange young couple who, like, break and enter and then live in other people’s houses. These other people are snowbirds, although I don’t think Williams actually employs the term: people who own houses on the barrier islands of Florida’s Gulf Coast which they, like, inhabit only a scant season or two a year. Breaking and Entering is very, very Florida, crammed with weirdos and tragedies, farcical, ironic, and thickly sauced in the laugh-cry flavor. I’m not sure exactly where it’s set, but I do know that I do know the general area—again, the barrier islands, skinny shining strips of weird between the Gulf and the Tampa Bay. Not my haunts, exactly, northeastern Florida man that I am, but still the locus of so many of my fondest memories, the places I return to, where my family is, where the cars and boats stacked up in the streets of Pass-a-Grille and Treasure Island and St. Pete Beach after the once-in-a-century storms that happen several times in a season, after Helene, after Milton, where the houses faltered folded soaked, where the snowbirds can defer their false falls and warm winters in favor of safer stabler climes, where the locals pledge a future allegiance against the heat, the water, the wind, the salt. A future against the future.