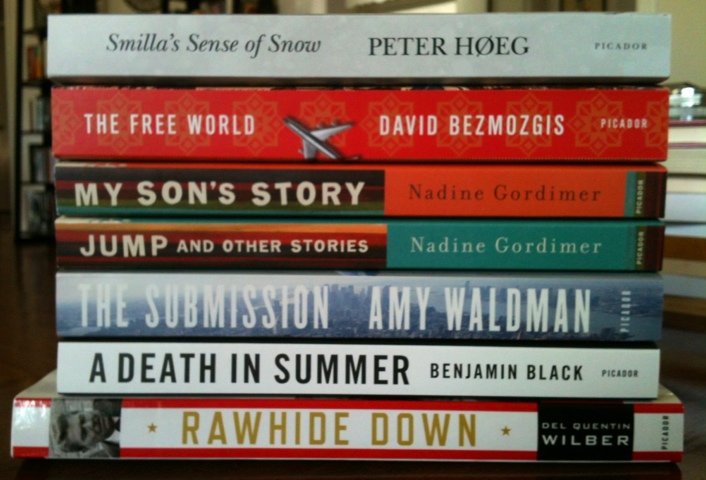

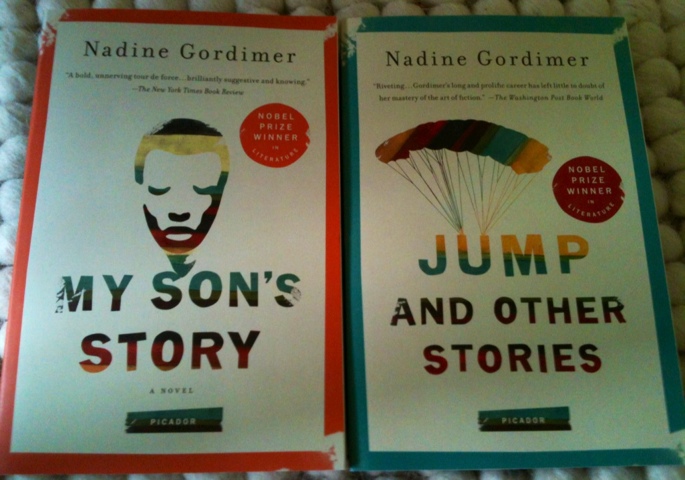

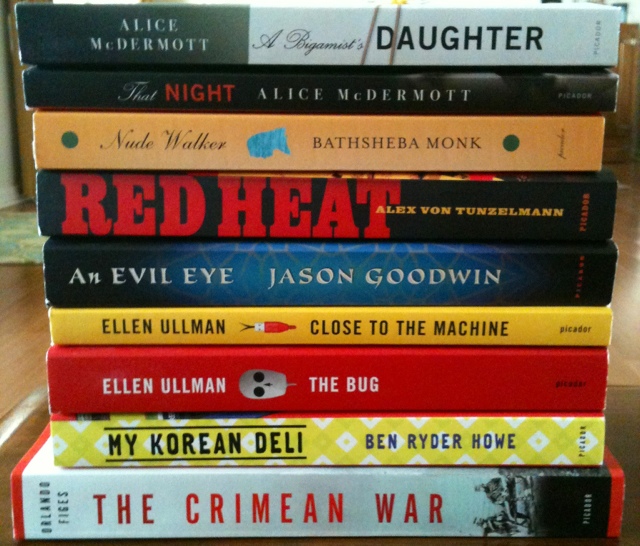

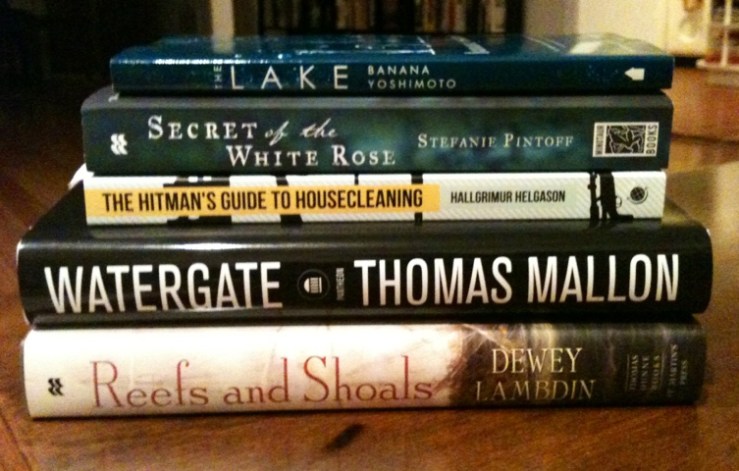

The kind folks at Picador sent a nice box of titles to Biblioklept World Headquarters a few weeks ago; I’ve had enough time to mull over them a bit and do something of a write-up. Here goes.

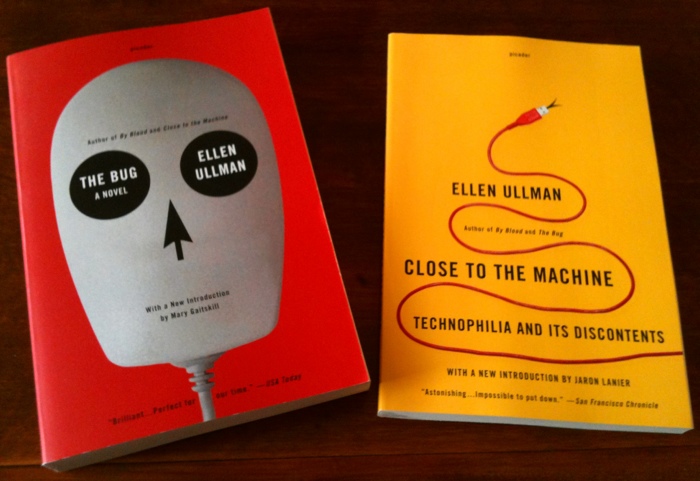

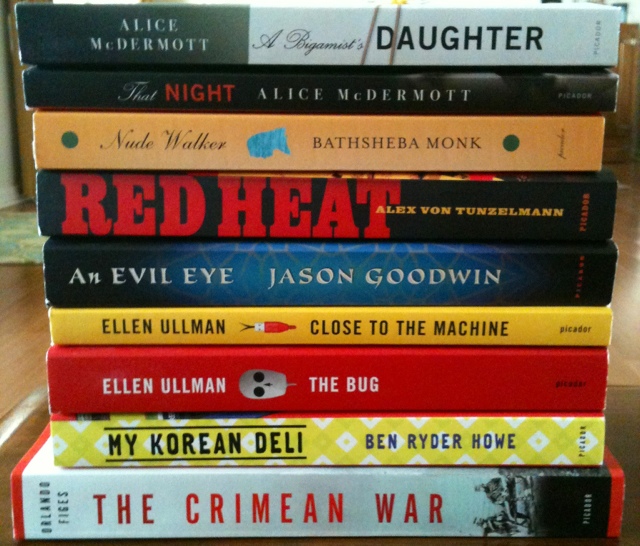

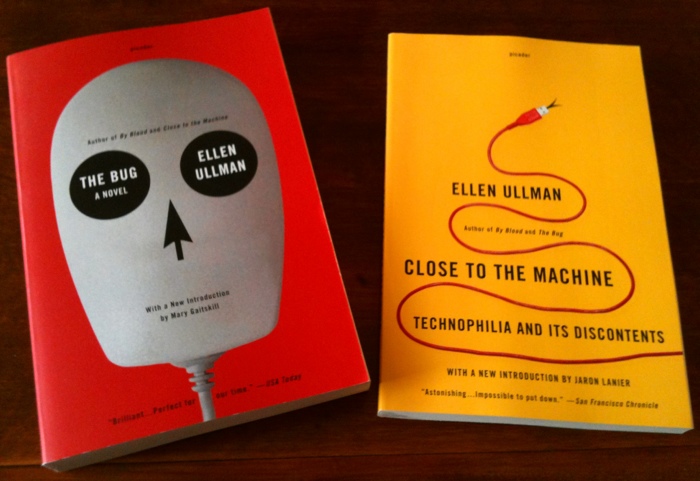

Next month, coinciding with her new novel By Blood (from FS&G), Picador re-releases (in new editions) two from Ellen Ullman:Close to the Machine and The Bug, which features a new introduction by Mary Gaitskill. Machine is a sort-of-memoir about the dawn of the tech-era; Ullman recounts her experiences as a female software engineer finding a place in the boys’ club of programming. Love these covers:

The Bug, a novel is tech without the noir, cyber without the punk—something different and fresh. It reminds me of Douglas Coupland’s Microserfs only because I can’t think of what else to compare it to. Pub’s write-up:

Ellen Ullman is a “rarity, a computer programmer with a poet’s feeling for language” (Laura Miller, Salon). The Bug breaks new ground in literary fiction, offering us a deep look into the internal lives of people in the technical world. Set in a start-up company in 1984, this highly acclaimed first novel explores what happens when a baffling software flaw—a bug so teasing it is named “the Jester”—threatens the survival of the humans beings who created it.

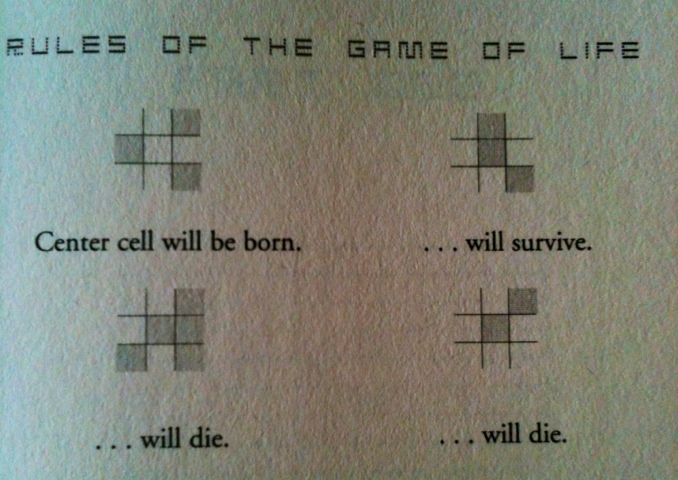

The Bug features a playfulness of the page, a willingness to examine the intersection of code and poetry. Example:

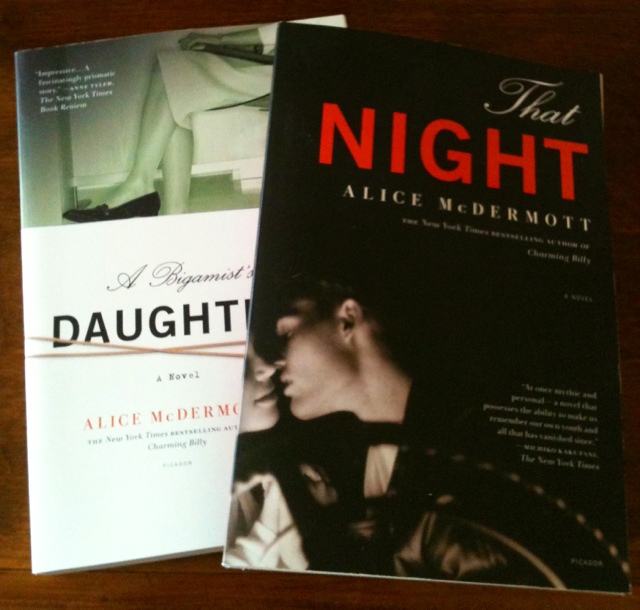

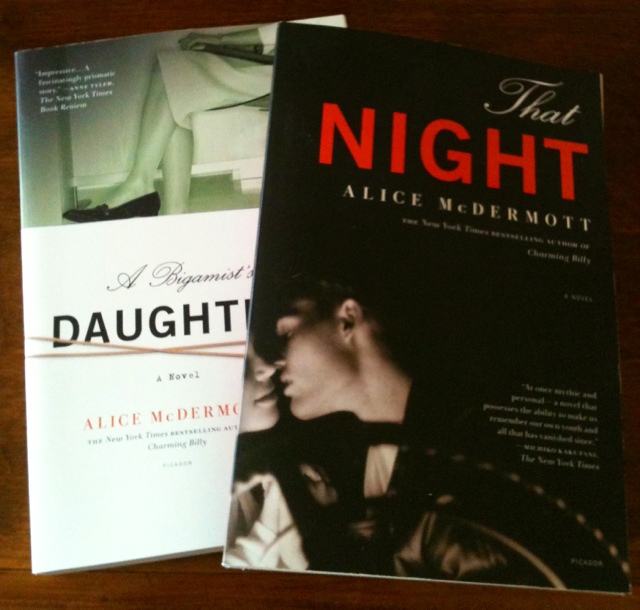

Alice McDermott also gets reissues: A Bigamist’s Daughter and That Night, which my wife picked up. That Night was a finalist for the Pulitzer and the National Book Award. It seems a little sexy and dangerous. Again, pub’s blurb:

It is high summer, the early 1960s. Sheryl and Rick, two Long Island teenagers, share an intense, all-consuming love. But Sheryl’s widowed mother steps between them, and one moonlit night Rick and a gang of hoodlums descend upon her quiet neighborhood. That night, driven by Rick’s determination to reclaim Sheryl, the young men provoke a violent confrontation, and as fathers step forward to protect their turf, notions of innocence belonging to both sides of the brawl are fractured forever. Alice McDermott’s That Night is “a moving and captivating novel, both celebration and elegy…a rare and memorable work” (The Cleveland Plain Dealer).

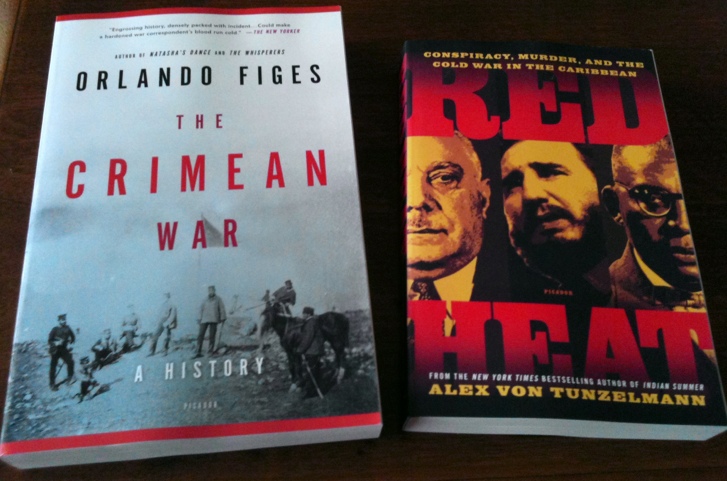

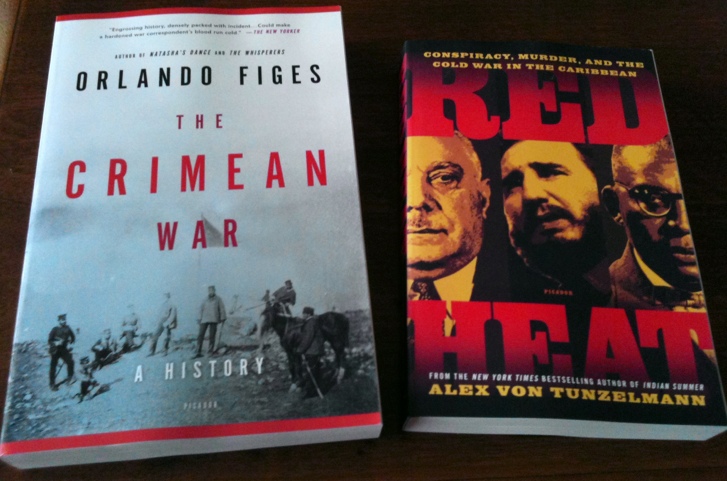

Two history books in the package: Orlando Figes’s The Crimean War and Red Heat by Alex von Tunzelmann.

Here’s an excerpt from the Figes book (which is, uh, about the Crimean War):

Two world wars have obscured the huge scale and enormous human cost of the Crimean War. Today it seems to us a relatively minor war; it is almost forgotten, like the plaques and gravestones in those churchyards. Even in the countries that took part in it (Russia, Britain, France, Piedmont-Sardinia in Italy and the Ottoman Empire, including those territories that would later make up Romania and Bulgaria) there are not many people today who could say what the Crimean War was all about. But for our ancestors before the First World War the Crimea was the major conflict of the nineteenth century, the most important war of their lifetimes, just as the world wars of the twentieth century are the dominant historical landmarks of our lives.

Red Heat is not the novelization of the 1988 Schwarzenegger buddy-cop film (nor, sadly, a novelization of the 1985 Linda Blair women-in-prison film of the same name). Von Tunzelmann’s book examines the relationship between the island nations to the U.S.’s immediate south to America and Russia. Like I said, no Schwarzenegger, but plenty of strong men. From Jad Adam’s review in The Guardian:

Red Heat deftly juggles the stories of three countries – Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic – and their relationship with the superpowers, where things were not as they seemed. Von Tunzelmann asserts that the political labels of the region were a sham: “democracy” was dictatorship; leaders veered to the rhetoric of the right or left according to advantage; a communist was anyone, however rightwing or nationalistic, whom the ruling regime wanted tarnished in the eyes of the US