[Editorial note: The following citations come from one-star Amazon reviews Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian. I’ve preserved the reviewers’ original punctuation and spelling. More one-star Amazon reviews.].

It may be art.

Damn McCarthy.

I find him boring.

unrelenting nihilism

The story is thin at best.

Are we supposed to enjoy it?

I felt abused by Blood Meridian

not a traditionally enjoyable book

this book is simply just not “all that”

wordy, over the top speechy dialogue

endless streams of dependent clauses

I am a devout fan of Cormac McCarthy.

The characters are not really sympathetic

He is obviously a sick man psychologically.

all about violence and no plot what so ever.

if I was a trained geologist I might like it better.

too many words that are not in standard dictionary

I guess people think he is cool because he writes so violent.

This one guy peed on some clay stuff to create a bomb like thing

murder, slaughter, killing, massacre, beating, stabbing, shooting, scalping

It consists of a series of almost unconnected scenes of unspeakable violence.

Esoteric words, eccentric expressions, pedantic philosophizing, arcane symbolism

I have to believe that he must be embarrassed to have this book back on the market.

A bunch of guys ride around Mexico killing everyone they come across for no particular reason

If you’re a fan of babies, quotation marks, and native americans, then avoid this book like the plague.

The reception he has had shows how tone deaf America has become to moral values, any moral values.

This book was written long before McCarthy had mastered the style that has brought him so much fame and credit.

the unrelenting amount of violence and cruelty in Blood Meridian strikes me as having crossed the line to pornography

It seemed like Cormac McCarthy wrote this with a dictionary in his lap trying to find words that he had never used before

Many of the words have to have been made up or are contractions of words and/or non-words, including much Spanish dialogue

Eliminate five words from the English language (“They rode on” and “He spat”)and this book would have been about 25 pages long

In this book, one sees him trying hard to hone his now-extraordinary powers of observation and description, and failing badly.

The standards for writing have clearly fallen far if all the praise heaped upon this inchoate, pompous mess of a novel is to be taken seriously.

Everything died: mules, horses, chickens, plants, rivers, snakes, babies, toddlers, boys, girls, women, men, ranchhands, bartenders, cowboys, good guys, bad guys…

I dont think the writer knows very much about AMERICAN history, the way he makes all the scalping get done by the AMERICANS and never by the indians, nor do I think he a PATRIOT

Wherein a company of men wander northern Mexico and the West killing, maiming, raping, and/or torturing everyone they meet, all described in gory, endless detail, led by the symbolic characters Glanton and his advisor, ‘the judge’, and supposedly illustrating that war and bloodletting are the only things that count, and the rest of life is just a meaningless dance.

Some kid with a few guys and a spattering of mans rambling through some part of the US or Mexico or a post-apocalyptic Australian desert seeing scores of gruesome, pointless scenes of violence, inhumanity, and death.

Holden is the sort of overt child defiling character who in real life wouldn’t last a month in a state penitentiary, because someone would rightly dispatch him as soon as possible.

Self-consciously faux-baroque linguistic stylings make this fetus-hurtin’ Treatise a feast for weakest link readers fascinated by the mark of the beast.

This book has some wonderful flowery language, and some beautiful descriptions of the southwest countryside.

They say that this book contains BIBLICAL themes, but I’ve read it and I don’t see how that could be so.

The author seems as if he is somehow trying to make some kind of “statement” about AMERICA

In a well ordered society McCarthy would be serving a life term or he would not exist at all.

there are times when it even seems as though English were not McCarthy’s first language

this book cannot be called a novel because it does not have character development

Would you let Cormac McCarthy look after your child for the night?

McCarthy is the most evil person because he is a talented writer

the author likes to use pronouns without establishing a subject

Who are the good guys and the bad guys, everyone is bad.

read Lonesome Dove instead, it’s a hundred times better

rampant nonstop mindless violence and depravity

I can’t dislike a book more than I dislike this one

This is a great writer being lazy and skating

good if you enjoy violence and nonsense

Theres lots of scalping of indians

Was there a quota on similes?

this booked scarred me

sociopath killers

It’s pure bunk.

a moral blight

utter trash

Ugh

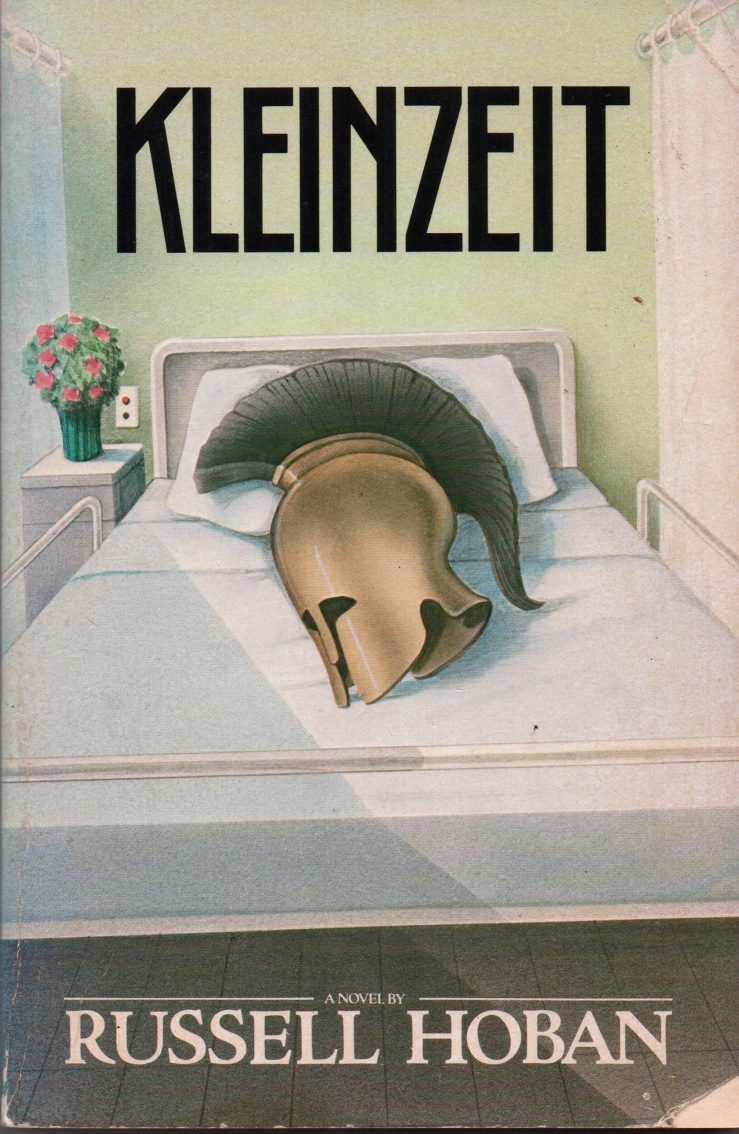

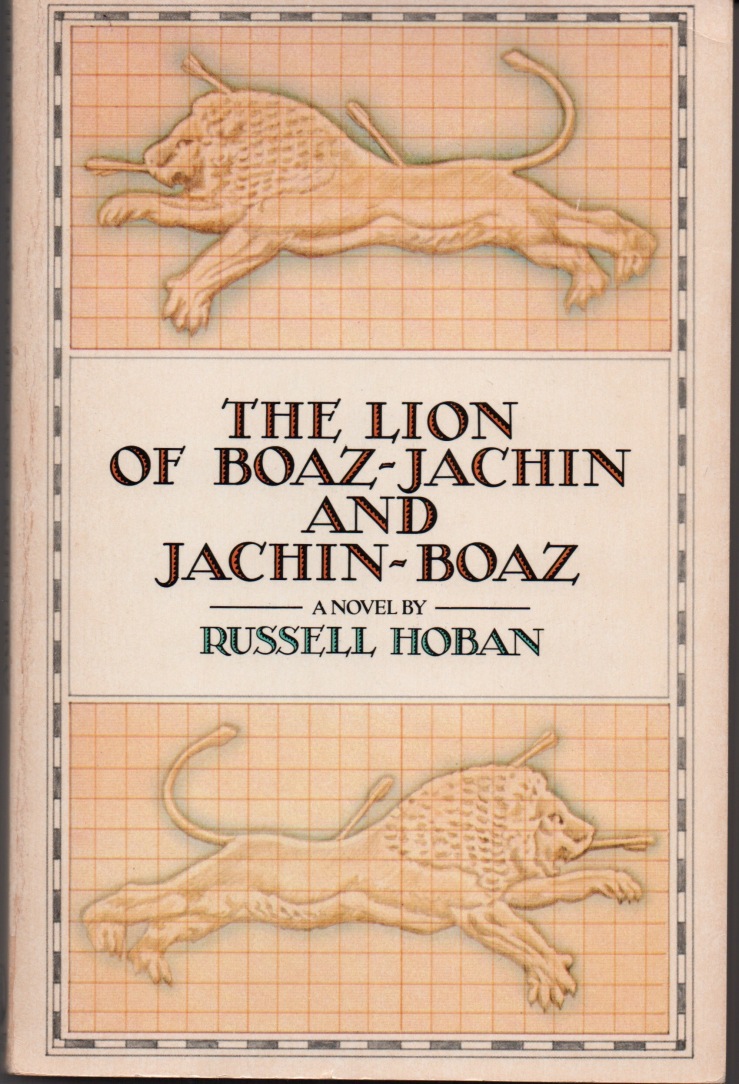

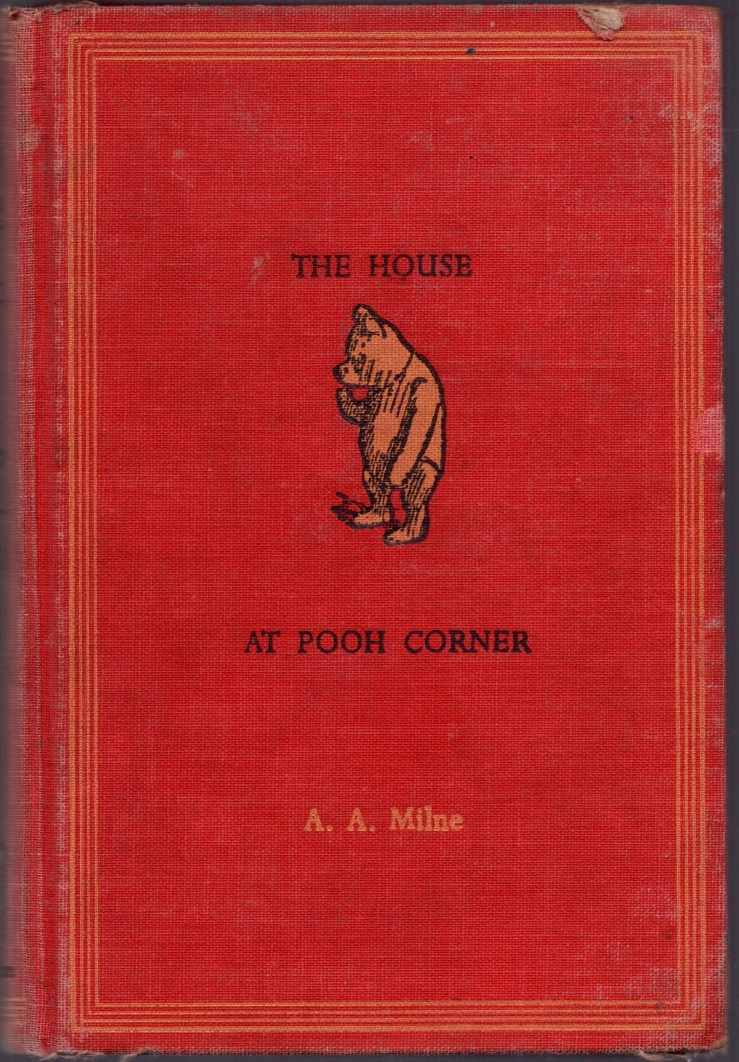

The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz by Russell Hoban. 1983 Summit Books trade paperback edition. Cover design by Fred Marcellino. Hoban’s first novel. Not my favorite Hoban.

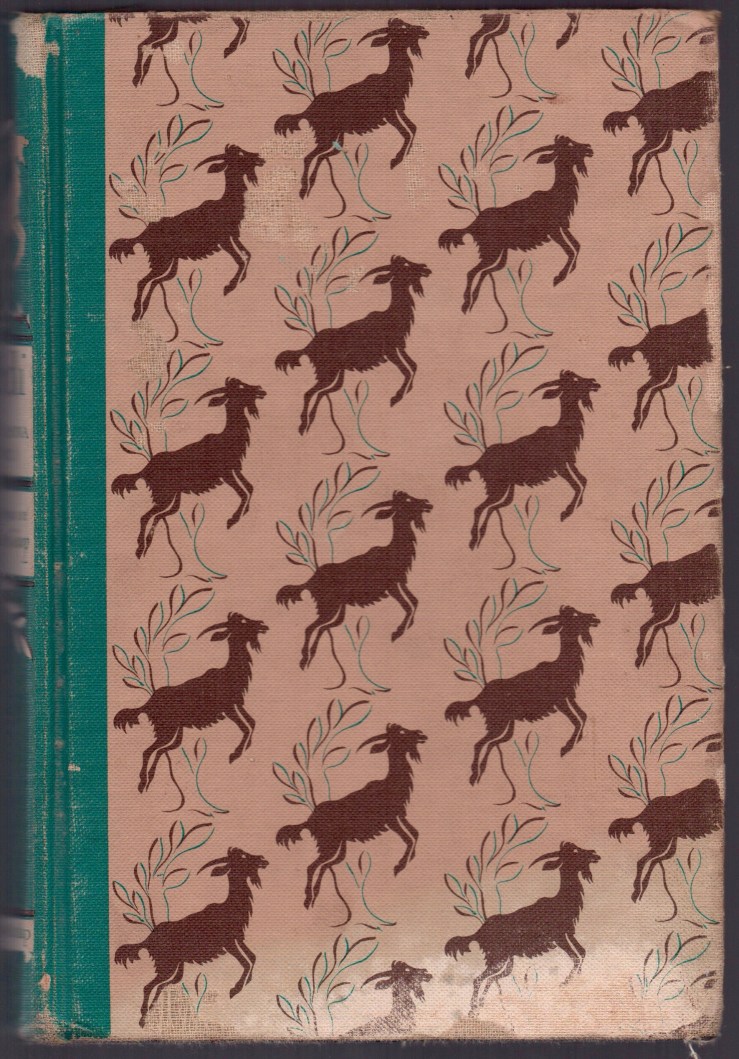

The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz by Russell Hoban. 1983 Summit Books trade paperback edition. Cover design by Fred Marcellino. Hoban’s first novel. Not my favorite Hoban. Pilgermann by Russell Hoban. 1984 Washington Square Press trade paperback. No designer is credited, but look closely under the horse’s fore hooves and note the signature “Rowena” — Rowena Morrill. (Note also the pig and naked lady). Pilgermann, Hoban’s follow-up (and somehow-sequel) to Riddley Walker, was the occasion for this Sunday’s Three Books post. I was reminded of this strange, wicked, dark, funny, apocalyptic book as I finished a reread of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and began Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant this weekend. Pilgermann is difficult but rewarding, and probably underappreciated, even as a cult novel.

Pilgermann by Russell Hoban. 1984 Washington Square Press trade paperback. No designer is credited, but look closely under the horse’s fore hooves and note the signature “Rowena” — Rowena Morrill. (Note also the pig and naked lady). Pilgermann, Hoban’s follow-up (and somehow-sequel) to Riddley Walker, was the occasion for this Sunday’s Three Books post. I was reminded of this strange, wicked, dark, funny, apocalyptic book as I finished a reread of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and began Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant this weekend. Pilgermann is difficult but rewarding, and probably underappreciated, even as a cult novel.

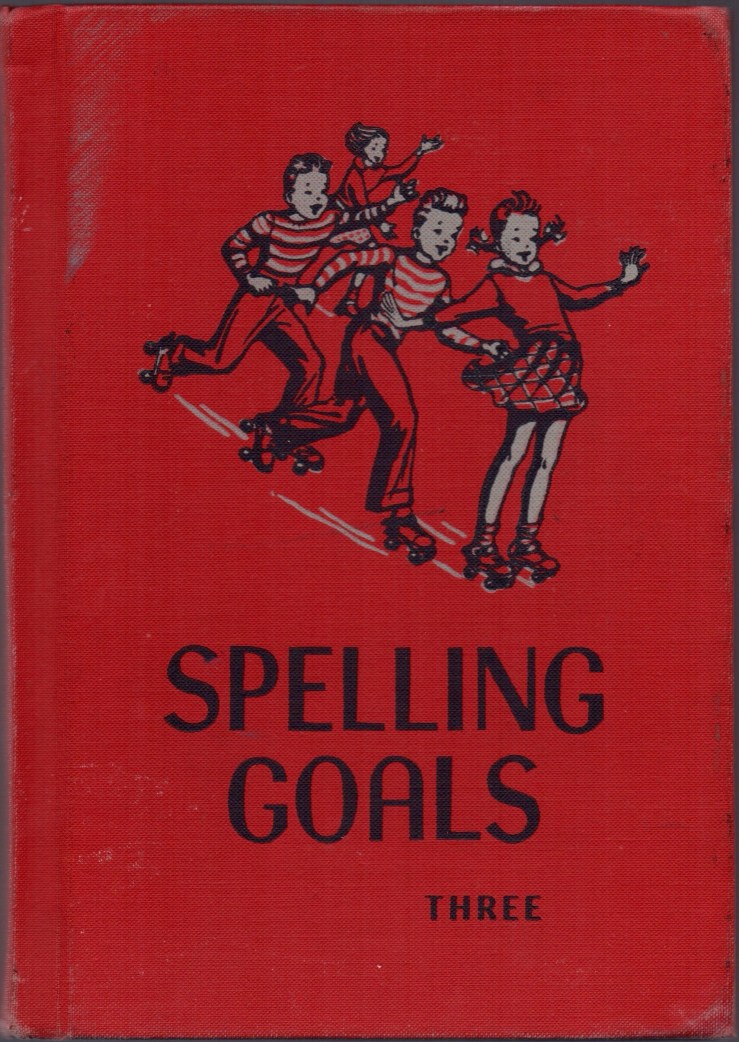

Heidi by Johanna Spyri. A 1945 Grosset & Dunlap Illustrated Junior Library hardback edition. Illustrations are by William Sharp, but no designer is credited for the hardback cover. My guess is that there was a dust jacket for this book at one point.

Heidi by Johanna Spyri. A 1945 Grosset & Dunlap Illustrated Junior Library hardback edition. Illustrations are by William Sharp, but no designer is credited for the hardback cover. My guess is that there was a dust jacket for this book at one point.

Fractured Karma by Tom Clark. First edition trade paperback from Black Sparrow Press. Design by Barbara Martin. The cover painting, Waiting Room for the Beyond, is by John Register. This is the first Tom Clark book I read. Amazing.

Fractured Karma by Tom Clark. First edition trade paperback from Black Sparrow Press. Design by Barbara Martin. The cover painting, Waiting Room for the Beyond, is by John Register. This is the first Tom Clark book I read. Amazing.